Man Dies

of Thirst in

Desert During

Survival Program

What matters more: The

Customer's welfare or his quest?

Rick Archer, May

2007

|

Editor's Note:

This story appeared in the Houston Chronicle in May 2007. It covers

the ordeal of Dave Bushow, a man who died of thirst in the desert

even though his guides carried water.

The incident took place in July 2006. However the story you

are about to read was published in the Chronicle in May 2007.

This the story was retold a year later when many facts in the story

become available through the Freedom of Information Act.

This story is a fascinating read because it calls directly into

judgment the actions of Mr. Bushow's guides during his ordeal.

|

|

Houston Chronicle

ED WHITE,

Associated Press Writer

May 2, 2007, 4:24PM

BOULDER, Utah —

It was Day 2 in the

blazing Utah desert. Dave Buschow was in

bad shape. Pale, wracked by cramps,

his speech slurred, the 29-year-old New Jersey man was desperate for

water and hallucinating so badly he mistook a tree for a person.

|

After going roughly 10 hours

without a drink in the 100-degree heat, he finally dropped

dead of thirst, face down in the dirt, less than 100 yards

from the goal: a cave with a pool of water.

But Buschow was no solitary soul, lost

and alone in the desert. He and 11 other hikers from various

walks of life were being led by expert guides on a

wilderness-survival adventure designed to test their

physical and mental toughness.

And the guides, it turned out, were carrying emergency

water on that torrid summer day.

However Buschow wasn't told that.

He wasn't offered any water for a

reason - the guides did not want him to fail the

$3,175 course.

They wanted him to dig deep, push himself beyond his known

limits, and make it to the cave on his own.

|

Nearly a year later, documents obtained by The

Associated Press under the Freedom of Information Act reveal those

and other previously undisclosed details of what turned out to be a

death march for Buschow. They also raise questions about the

judgments and priorities of the guides at the Boulder Outdoor

Survival School. What matters more: the customer's welfare or his

quest?

"It was so needless. What a shame. It didn't have to happen," said

Ray Gardner, the Garfield County sheriff's deputy who hiked six

miles to recover Buschow's body. "They had emergency water right

there. I would have given him a drink."

The family

members were furious.

"Down in those canyons it's like a furnace," said Rob

Buschow of Glen Spey, N.Y.

"I don't have my brother anymore because no one would give

him water."

|

|

While regretting the tragedy, the school,

known as BOSS, has denied any negligence and instead blamed Buschow,

saying the security officer and former Air Force airman did not read

course materials, may have withheld health information and may have

eaten too heavily before leaving River Vale, N.J., for the grueling

course.

Noting Buschow signed liability waivers, the school said: "Mr.

Buschow expressly assumed the risk of serious injury or death prior

to participating."

Garfield County authorities declined

to file charges, saying there was insufficient evidence the

school acted with criminal negligence. The prosecutor said

participants knew they were taking a risk.

The U.S. Forest Service, however, has stopped BOSS from

using Dixie National Forest for a portion of the 28-day

course this summer until it gets outside advice on providing

food and water.

The agency said it was the first death of a participant in a

BOSS survival exercise.

|

|

The Colorado-based school dates to the late

1960s. In 1994, BOSS alumnus Josh Bernstein, a New Yorker with an

Ivy League education, took over marketing and administration and

later became owner. He also is host of the History Channel's

"Digging for the Truth," a show that takes viewers on archaeological

adventures around the world.

BOSS has wilderness courses lasting just a few

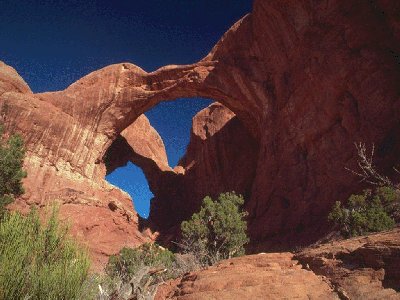

days to a month. During the 28-day survival course, held 250 miles

from Salt Lake City, campers are required to hike for miles and

drink what they can find from natural sources.

BOSS emphasizes personal growth

through adversity, and using your wits to survive. The

mantra: "Know more, carry less."

Tent, matches, compass, sleeping bag,

portable stove, watch — all have no role. Campers are

equipped with a knife, water cup, blanket and poncho and are

told they could lose 20 pounds or more. Among the things

they learn is how to catch fish with their hands and how to

kill a sheep with a knife.

The course is intended to push people "past those false

limits your mind has set for your body."

"Somewhere along the many miles of

sagebrush flats, red rock canyons, and mesa tops of Southern

Utah — somewhere between the thirst, the hunger and the

sweat — you'll discover the real destination: yourself,"

BOSS says on its Web site.

Buschow had marched the arctic tundra in Greenland. And

after leaving the Air Force, he worked security at U.S.

bases outside the country. He recalled his days as a Boy

Scout in his May 2006 application to BOSS.

|

|

"Although in the yrs since, I have continued

to appreciate Mother Nature," he wrote by hand, "I still haven't

ever truly immersed myself in her embrace. I fear that I'm becoming

a 'comfort camper,' having never come close to looking her in the

eyes."

Buschow described himself as 5-foot-7 and about 180 pounds, with a

resting pulse of 66. A New York doctor checked a box declaring him

fit for a survival program. Buschow signed the application,

acknowledging that BOSS was not offering a "risk-free wilderness

experience."

|

The documents obtained by the AP

disclose the brief but bitter wilderness adventure of

Buschow:

On July 16, he gathered here with the 11 others, including

some from England and a college student who had bicycled

from Maine. Most were in their 20s and 30s. They ran 1 1/2

miles so the staff could assess their conditioning.

Buschow "was not the most in-shape but not the most out of

shape either," recalled camper

Charlie DeTar, 25, the cross-country bicyclist.

On the second day, after a cool night,

the group set out around sunrise and stopped about 8:30 a.m.

to dip their cups into Deer Creek in what turned out to be

the only water until evening. Buschow pulled a bottle from

his pack — but was warned by the staff not to fill it.

During the early phase of the

expedition, participants can drink water at the source only

and cannot carry it with them.

The group, led by three guides, formed a loose chain, with

stronger hikers ahead of people struggling at the 6,000-foot

elevation, or more than a mile above sea level.

"We didn't cover all that much distance, maybe five to six

miles. We were moving slowly, a lot of up and down," DeTar

said in an interview from Vermont. "You don't have food, you

don't have water, so you have to move at the slowest pace of

the group."

|

They rested periodically under pinons and

junipers, all the while looking for signs of water, such as green

vegetation in canyon bottoms. At least two attempts to dig for water

failed.

Not everyone had close contact with

Buschow, but a consensus emerges from the campers' written

accounts obtained by the AP: While cheerful, encouraging and

coherent at times, he was a man in deep trouble hours before

he collapsed.

"We were all desperate for water," a

camper wrote. "Every time (Buschow) would fall or lie down,

it took a huge amount of effort to pick him back up. His

speech was thick and his mouth swollen."

|

|

"Every time he continued, he'd rush ahead,

often in the wrong direction and so exhausting himself even more,"

the camper wrote.

The sun was described as blazing, inescapable. "There were no

clouds," a camper wrote.

Some people vomited that day, including a man who got sick three

times — a typical misery on the rigorous course, according to BOSS.

Buschow was suffering from leg cramps about 2:30 p.m. and said he

was feeling "bad."

During a break, he mistook a tree for a person and said, "There she

is."

|

"This was the first point at which I

became concerned knowing that delirium happens when

dehydration becomes severe," a camper wrote. Buschow "also

asked if there was much air traffic that went through here,

and asked if anyone had a signal mirror."

(The Forest Service, citing privacy concerns, deleted

certain names from documents.)

By 7 p.m., as the sun descended and temperatures cooled a

bit, the group approached a cave in Cottonwood Canyon, known

to BOSS guides as a reliable source of water.

Buschow's companions were carrying his possessions for him.

Within earshot of people exhilarated about the pool of

water, he collapsed for the last time.

"He said he could not go on," staff member Shawn O'Neal

wrote two days later in a statement ordered by the Garfield

County Sheriff's Office. "I felt that he could make it this

short distance and told him he could do it as I have seen

many students sore, dehydrated and saying 'can't' do

something only to find that they have strength beyond their

conceived limits."

O'Neal didn't inform Buschow about his emergency water.

"I wanted him to accomplish getting to the water and the

cave for rest," he wrote. "He asked me to go get the water

for him. I said I was not going to leave him. ... Shortly

thereafter I had a bad feeling and turned to Dave and found

no sign of breathing.

|

A staff apprentice climbed to the top of a

dead juniper to get reception for a cellular call to the Boulder

office.

Five people took turns trying to revive Buschow while red biting

ants crawled over his face. A rescue helicopter from Page, Ariz.,

arrived about 90 minutes after he passed out, but a defibrillator

failed to jump-start his heart. Campers gathered in a circle for the

news: "Dave is dead."

They had a moment of silence and ate almonds, sesame sticks and

energy bars distributed by staff, the first food since sandwiches

more than 24 hours earlier.

Buschow's death was caused by dehydration and electrolyte imbalance,

according to Dr. Edward Leis, Utah's deputy chief medical examiner,

who found no evidence of drugs or other factors.

After Buschow's death, five people left the course. The six campers

who completed the exercise returned to the site to leave a bouquet

of foliage and a marker of stones.

|

DeTar, a camper who performed CPR,

said no one was told that BOSS guides carried emergency

water, but "I heard it slosh" in a pack.

Should the water have been offered

to Buschow? And if it's for an emergency, what triggers it?

"Hard to say," said DeTar, who has a master's degree from

Dartmouth College and is trained in wilderness first aid.

"One thing that BOSS offers you is an opportunity to push

yourself physically into the red zone. ... He was 200 feet

from the water. Is that the

point where you give it to him? Or 500 feet?"

Bernstein, the school's owner, agreed to answer questions

only by e-mail. He said BOSS instructors can give water

based on their assessment of a camper's needs.

"The group appeared to be within the normal parameters we've

seen on the trail over the years," Bernstein said. "Many

hikers were, understandably,

tired, but morale was high and the participants were

determined to continue. ... He seemed capable of completing

the hike to camp that evening."

In a Feb. 27 letter to the Forest Service, Bernstein said

Buschow may not have trained properly, pointing to comments

he made to another camper about drinking a gallon of water a

day and eating cheese steaks to

bulk up before the expedition.

His brother, Rob Buschow, said: "It's sickening when they

blame the victim."

|

|

You Be the Judge

Obviously in retrospect, if the guides had

known how serious Mr. Buschow's condition was, they would have given

Mr. Buschow the much-needed water.

Similar incidents have been reported with teenagers dying in the

summer heat as they underwent conditioning exercises to prepare for

football season. Coaches will withhold water to toughen them

up, a very risky move. Heat and football are a dangerous mix.

For example, a professional football player from the Vikings died of

heat stroke during training camp in August 2001.

And of course Boot Camp Drill Instructors are legendary for pushing

recruits to their limits.

Who decides when enough is enough?

In the case of Mr. Buschow, what do you think the courts will

decide?

Email your thoughts to Rick Archer,

dance@ssqq.com

|

|