|

CHAPTER

EIGHTY SEVEN:

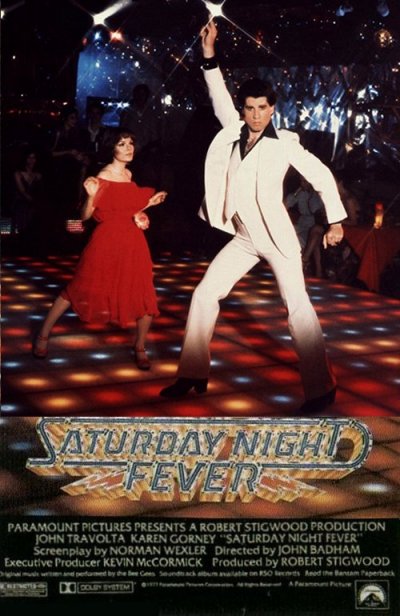

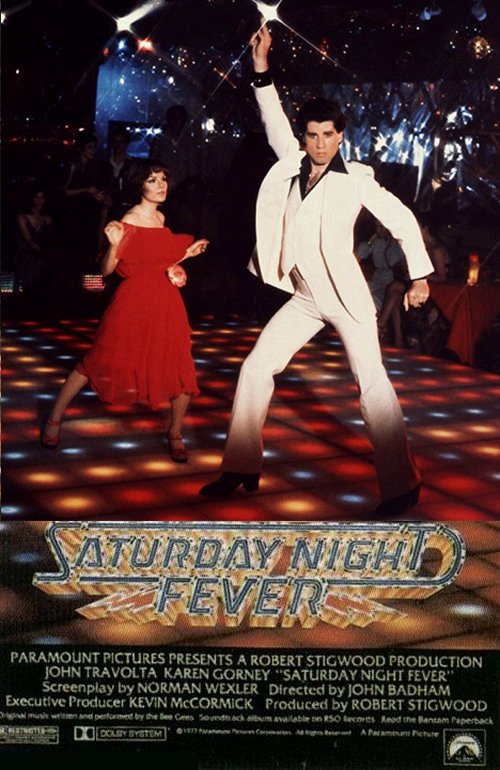

SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER

Written by Rick Archer

|

|

SUBCHAPTER 366

-

The Inside

Story of Saturday Night Fever

|

Rick Archer's Note:

I am a

strong believer in Fate. Due to 100 unusual

experiences from my life, I have come to believe my

dance career was predetermined.

Magic Carpet Ride

is the book I have

written to explain the unusual circumstances of how

my dance career started. The key event was the

unexpected appearance of

Saturday Night Fever in December 1977.

This unknown sleeper movie became a supernova which

launched my dance career into orbit. Considering the

movie's dramatic impact on my life, when I began to

write my book, I decided to study the events that led to the movie's creation. To be

frank, I was so astonished by what I learned, I

believe the making of this movie is just as much a

Supernatural situation as the events surrounding my

own story.

Assuming I am correct in my

conclusions, then I am hardly the only person whose

life has been directly affected by Fate. I

daresay John Travolta would be the first person to

agree with me on the existence of Fate. But

why stop there? As we shall see, there was an

entire boatload of weird curiosities surrounding Saturday Night Fever.

Saturday Night Fever became the

career-defining moment for eight different men -

Producer Robert Stigwood, Actor John Travolta, the

three Bee Gees, Story Writer Nik Cohn,

Screen Writer Norman Wexler, and 'New York' Magazine Editor Clay Felker.

Seven of

these men would become rich and famous beyond their

wildest imagination. However, not everyone

thrived. One

man failed to make a dime. Not only that, his

career and reputation were ruined in

the process. Two years later, this broken man became the main

reason I would one day own the largest dance studio

in America. But we will save the story of

Urban Cowboy for later. Right now,

the recent 2020 HBO special on the

Bee Gees parallels this story to

perfection. If you have not seen this special,

you should do so. It is very well done.

I decided to share this story because it will help

you understand many of the events in the two-hour

Bee Gee documentary.

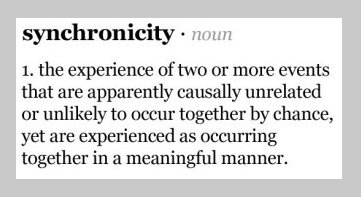

The

story behind Saturday Night Fever serves as the most perfect example of

'Synchronicity' I have ever witnessed. I understand this is a bold

statement, so let me share the unusual story of

Saturday Night Fever. Then my Readers

can reach a conclusion whether Fate played a role

here. I will be curious to know what you

decide.

Rick

Archer,

dance@ssqq.com

|

|

|

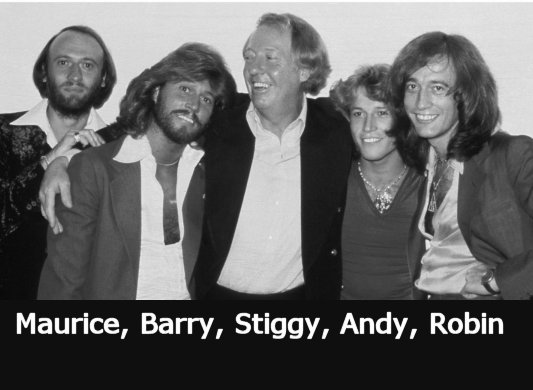

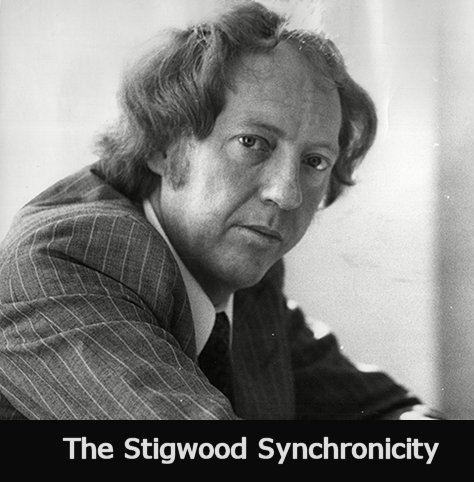

SUBCHAPTER 367 -

PRODUCER ROBERT STIGWOOD

|

When it came to Saturday Night Fever, Robert

Stigwood was unbelievably fortunate. However, he wasn't

just lucky, there is considerable evidence that he also

benefitted from 'Dumb Luck', i.e. a situation when someone

succeeds in spite of themselves.

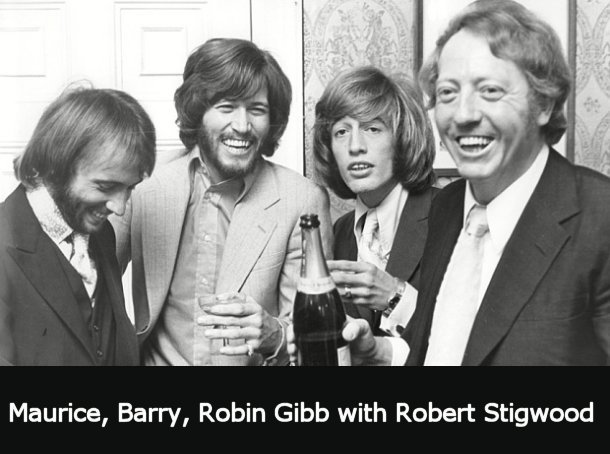

Robert

Stigwood (1934-2016) began his career as a music

producer. Born in Australia, Stigwood moved to England at age

21. Stigwood had a college degree, but no idea what to do with it. After a series of dead-end jobs, Stigwood discovered he had an interest in promoting local

rock bands in Portsmouth.

Stigwood got his start in the mid-Sixties as the manager of

future rock star Eric Clapton. It was Stigwood's idea to pair Clapton

with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker. This led to

Cream, the superstar rock band that briefly rivaled the fame

of the Beatles and Rolling Stones.

Along the way, Stigwood managed The Who (Tommy, Pinball

Wizard)

as well as the Bee Gees from Australia.

The three Bee

Gee brothers were in awe of Stigwood. They described

him as a creative genius with a very quick and very dry wit.

Stigwood was an aggressive manager who wasn't afraid to take

chances. Stigwood had a favorite saying.

"There are a lot

of ways to become a failure, but never taking a chance is

the most effective."

Unfortunately, Stigwood's bold

style got him in a lot of trouble early in his career. Stigwood

was the

victim of a bad move that led to one of the funniest

anecdotes in

rock 'n roll history.

In 1966, Robert Stigwood tried to poach another manager's

act into his own fold. The manager, Don Arden, took

exception.

Don Arden: "I had to stop

these overtures – and quickly! I contacted two

well-muscled friends and hired two more equally huge

toughs. The five of us went along to nail this cocky impresario to his

chair with fright.

There was a large ornate ashtray on

his desk. I picked it up and smashed it down with such

force that the desk cracked. I gave a good impression

of a man wild with rage.

My friends and I

had carefully rehearsed our next move. I pretended to go

berserk. I lifted Stigwood bodily from his chair,

dragged him on to the balcony and held him by his feet.

Stigwood screamed as he

looked down at the pavement four floors below. I asked

my friends if I should drop him or forgive him. In

unison they shouted: 'Yeah, do it! Go ahead and

drop the son of a bitch!'

Stigwood went

so rigid

with shock, I thought he might have a heart

attack, so I quickly dragged him back into the

room. I warned him never to interfere with my

groups again."

Stigwood learned his lesson. From that point on, Stigwood

stayed closer to the rules and enjoyed considerable success.

|

|

SUBCHAPTER 368

-

CLAY FELKER

|

|

If I

can make it there, I'll make it anywhere,

Come on, come through, New York, New York.

-- Frank

Sinatra, 'New York, New York'

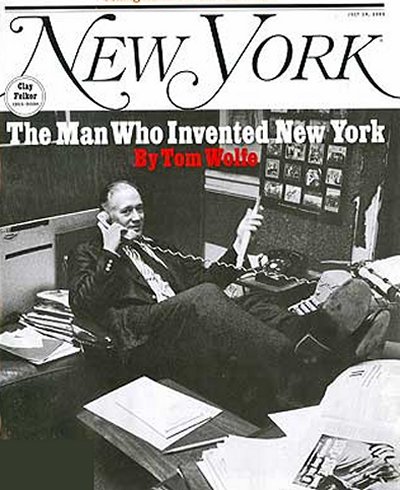

Clay Felker

(1925-2008) was the man who breathed life into

Saturday Night Fever. He was the embodiment of Sinatra's

New York, New York. If Felker could make

it there, he could make it anywhere. Coming from

Missouri, Felker was an outsider who wanted to be an

insider. He succeeded royally. As editor of New York, one of the city's most

influential magazines, Clay Felker became the

ultimate New York insider.

Clay Felker was said to be one of the best-connected

people in the media business. A celebrated

man about town, Felker made it his

job to know

every important person in news, television, politics, theater,

music,

fashion, Wall Street and Hollywood. As his

writer friend Tom Wolfe put it, "Clay Felker was the

man who invented New York."

Throughout his

career, Clay Felker was known as a 'trend-spotter'.

Felker's special genius was his ability to see what was breaking

before anyone else. Felker

was quoted about his love for

trend-spotting. "Journalism is very often about

the future."

This was a

fitting observation from a man who practiced what he preached

time and again. Felker's passion was to

stay ahead of the curve. As a magazine editor,

Felker understood the importance of reporting on

interesting developments well in advance of his

competitors. Therefore he kept a keen eye out for

stories that would capture the public's interest

before they became obvious.

|

|

|

Sometimes

Felker went one step further. He would see something that

might be ready to happen, then authorize a story to

cause it to

actually happen. Taking pride in spotting cultural

trends before

anyone else,

Clay Felker reveled in providing the spark that lit the fire.

Intimately

connected to the pulse of America, Clay Felker was

one of the most influential journalists of his time.

Back in the Sixties and Seventies, Clay Felker was the legendary editor of

New York magazine. Felker not only

helped found the

The Village Voice, he also helped

his friend Gloria Steinem start

Ms magazine. In 1977 Felker

moved on to

Esquire magazine.

Subjects near and dear to Felker's heart were

'Status' and 'Subcultures'. Or 'Haves and Have Nots' as he

put it. Status came first. Felker was intensely

curious about the rich. Fascinated

by ambition and social climbing, his preoccupation developed because

Felker was a social climber himself. He wanted to

be just as famous as the people he associated with.

Felker believed he was defined by the company he kept.

Therefore he constantly surrounded himself with important celebrities.

In this way Felker expected to become a celebrity in his own right.

The method he

used to make himself important was ingenious. Fascinated

by the

nuances of power and status in the city, he found a

unique way to obtain the inside information New York

magazine was famous for. Felker had a fabulous

apartment at 322 East 57th where he threw the most

lavish parties in New York City. His parties were said

to be the ideal place to rub shoulders with the rich, the elite

and the talented. Tom

Wolfe joked that Felker's vast fireplace was such an inviting

place to be noticed that 'fourteen status

seekers would sit there all at the same time'.

|

Felker had paid his dues as he worked his way to the

editor's position at New York. In

so doing, the magazine had become his baby. Now that

he was meeting the movers and

shakers of New York City on a regular basis, he realized how obsessed with Status

they were. Felker understood their motto was to see the best and

to be seen by the best. Why not be the guy who brings

them together? Using his unique position, Felker was

able to grant attention to many of the world's celebrities,

people who were dying to be noticed as often as possible.

Felker discovered if he put important people from different power

corridors in contact with each other, they would

begin to gossip and unleash a treasure trove of trade

secrets. With a martini in one hand and a

beautiful woman in the other, Felker would listen in as they exchanged ideas.

Any time the stories became juicier, Felker would snap his fingers to ensure another

martini would be produced on demand. Felker smiled

as people dropped one story after another into his

lap. Felker knew exactly what he was

doing... and so did his guests.

Felker became the quintessential New York insider with his

swashbuckling air of confidence and his custom-made clothes.

Using his stunning movie star wife Pamela Tiffin as arm decoration, Felker had no trouble holding his own

with the Beautiful People. Due to the publicity his

magazine generated, Felker's triumph was being as important

to them as they were to him.

By making his parties and his magazine inseparable, New York

became the direct extension of those smart

Upper East Side dinner parties.

Every celebrity knew they could promote their latest movie

or book by attending. Every politician could test run

their latest policies. Every cat and shrew could exact

revenge by dropping dirty tidbits. Having obtained the

power to elevate or reduce Status, Felker was now the city's

ultimate gossip columnist. Engaging his guests in

juicy talk on topics such as

politics, real estate, business,

and prominent people misbehaving, Felker used his dinner parties to keep a close finger on the pulse of the town.

|

|

On Monday morning, Felker would weave all the name dropping

and gossip tidbits into his next set of

stories. He would keep his sources anonymous of

course, but a cursory scan of his most recent guest list would

typically

suggest the likely identity.

Felker made his magazine a must-read for the movers

and shakers of America's premier city. New York

magazine became the style guide for every hip artist,

wealthy socialite, ambitious politician and shrewd businessman looking

for an angle.

Everyone knew that each issue would contain something sharp, well-informed, and 'trendy'.

Felker's

parties at his tony East 57th Street apartment were

a popular destination for glamorous people vying for

a cover story. Others came in hopes of hearing a lucky

Wall Street tip. Everyone knew

a chance conversation with the right person could

lead to a career break. No one turned down a

Felker party invitation.

Felker was curious about finding hidden nuggets as well. Felker

understood the sub-cultures were not going to come to him,

so he was on the lookout wherever he went. Clay Felker

had a stable of creative writers to choose from. As the

ultimate 'trend spotter', Felker made it his business to

notice something interesting, then go find one of his gifted writers to poke his or her nose into

it.

|

|

|

|

|

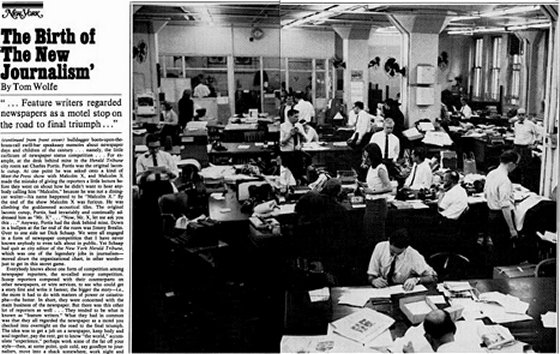

"New York

was the magazine that helped create the notion of the writer

as star," said Ken Auletta, one of Felker's writers, to

the

Washington Post in 1993. "Felker made his

writers famous."

Tom Wolfe was Felker's first

breakout star. New York specialized in

reporting the heady

confusion of the difficult Seventies. Felker took

special delight in stories where the Ins and the Outs

interfaced awkwardly. One such story was Tom Wolfe's

"Radical Chic" which described a strange fundraiser for the Black

Panthers at the apartment of famous conductor Leonard Bernstein.

Wolfe's scathing story, which coined the term 'limousine

liberals', became a classic example of the 'New Journalism'.

Six years later, Wolfe would sum up the entire era when he

called it the 'Me Decade'.

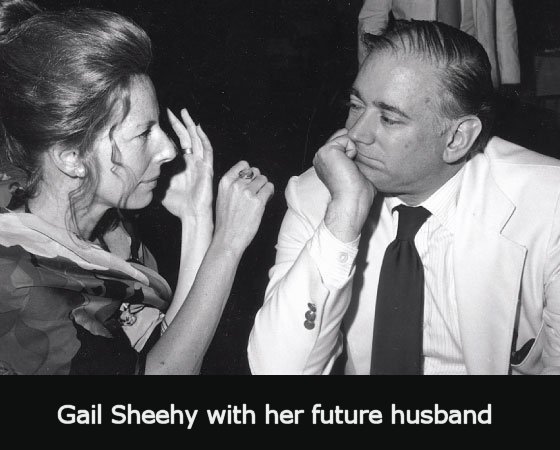

Gail Sheehy was another writer Felker encouraged. Sheehy was an early feminist.

She first came to fame by writing about how women negotiated a

Man's World during the Sixties. Like her counterpart

Tom Wolfe, Sheehy had a gift for the clever phrase.

Here is a classic example Sheehy used to describe aggressive women in

singles bars.

"Booted,

pant-suited, birth-controlled and pleasure-goaled."

Gail Sheehy's vivid 1971 reporting on

hookers in New York was the perfect example of Felker's

trend-spotting and reliance on his writers to bring the

story to press. Felker suggested to Sheehy that she investigate

prostitution from a very unusual angle.

Gail Sheehy took the hint. Putting away her notepad, Sheehy took to the streets wearing hot pants, white

vinyl boots and a revealing top.

Behind puffed up

hair and too much makeup, the disguise worked to perfection.

Showing considerable moxie, Sheehy mingled with the working girls

to get some straight talk. What Sheehy brought back to

Felker was an astonishing eyewitness account of the sex

trade. Sheehy's articles caused a firestorm of

controversy. It seems many of the city's richest, most

powerful families and corporations benefited directly and

indirectly from the illegal sex business.

Sheehy's story and others like it created sensation and

controversy.

Be it Gail Sheehy or Tom Wolfe, stepping on people's toes was a Felker specialty.

Someone was always mad at Clay

Felker for something one of his writers had written

about them. This was what Clay Felker lived

for. It did not take long until Felker's magazine

was on the tip of everyone's tongue. Who would be

'Felkerized' next?

Tom Wolfe said

that Clay Felker

helped New York discover its

own identity. Felker also

changed the face of magazines.

Be

it drugs, counterculture, feminism, obsession with status, Clay

Felker encouraged citizens to take a close look at

themselves. By noticing what was interesting about everyday places and

people, Clay Felker became the inspiration for adding the Lifestyle

section to the American newspaper, a feature we now take for

granted.

Gail Sheehy married Felker in 1984. After his passing

in 2008, she said her husband was an inspiration to many writers. Sheehy

pointed out that

Felker presided as editing God to an explosion of

creative nonfiction back in the Sixties... Tom Wolfe, Truman

Capote, Joan Didion, Jimmy Breslin, Norman Mailer, Hunter Thompson,

Nora Ephron, Gloria Steinem, and Aaron Latham. And let's not

overlook Gail Sheehy. Her 1976 book Passages was

named by the Library of Congress one of the ten most

influential books of our times.

Tom Wolfe, Felker's

first superstar, turned a Felker suggestion into The Electric

Kool-Aid Acid Test, a fascinating book on the

counter-culture. Nor did he stop there. Tom Wolfe went on to become a best-selling author with books like

Bonfire of the Vanities

and The Right Stuff. Wolfe was eternally

grateful to the man who gave him his start. He never forgot who

his mentor was. In a 1993 interview with the Washington Post, Tom Wolfe

called Clay Felker "the greatest idea man that ever

existed."

|

SUBCHAPTER 369 -

NIK THE

SLIK

|

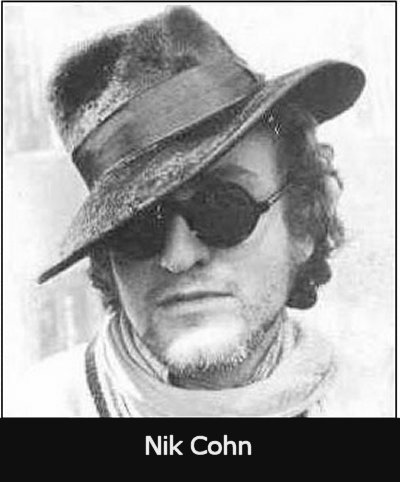

Nik Cohn was the next piece of the Saturday Night

Fever puzzle. Born in London in 1946, Cohn got his

start as a rock critic. Always the clever guy, by the

age of 18 Cohn was a fixture on the swinging London Mod

scene of the late Sixties. He partied with rock stars

and hung out with his celebrity friends on tours.

In a manner similar to Clay Felker, Nik Cohn parlayed his

insider connections at these parties into a job.

With an ear for gossip, Cohn figured out a way to make

money off the fame of his companions. He contributed briefings about mods and rockers to

The Observer. Along the way, Cohn wrote

a 1969 book about the history of rock 'n roll in Britain

during the Sixties.

Nik Cohn had an odd claim to fame. Cohn

was a close friend of Peter Townshend, lead singer of

The

Who. Cohn was an avowed pinball maniac and

Townshend loved watching him play. Cohn's obsession

with the pinball machine became the inspiration for

Townshend’s classic song Pinball Wizard.

Cohn was an adept social climber. As journalist and

media critic, he cultivated a circle of important contacts within

the British music business. After he became friends

with Peter Townshend, it was inevitable that Cohn would rub

elbows with Robert Stigwood, manager and booking agent of The Who.

The illustrious rock band became Nik Cohn's

connection to Stigwood's business operations. Cohn

spent considerable time on the set during the 1974 filming of Stigwood's

film version of Tommy featuring The Who.

In the process Nik Cohn became

a close friend with Bill Oakes,

president of RSO Records (Robert Stigwood

Organization). As so the social climbing

continued.

In 1975, Bill Oakes invited Cohn to come join him in New York.

After crossing the Atlantic, Cohn crashed on the couch in

Oakes' apartment. Oakes got Cohn an interview with

New York

magazine. Cohn was hired to cover the New York music scene.

One night Nik Cohn followed a tip and took a taxi over to

Brooklyn. He visited a nightclub known as

2001 Odyssey,

a Disco hotbed. Previously

Disco had been a phenomenon

limited to New York's gay bars. Cohn found it

interesting that this new style of dancing had

migrated to a working class neighborhood.

Cohn's visit

to the Disco gave

him an idea. It seemed to him that

Disco was spreading like a virus.

Cohn's experience with the music scene suggested there was a story

here. Cohn went

back to Oakes' apartment and immediately started writing.

Cohn's first

idea had been to pitch this idea to Clay Felker at New York

magazine. Then it crossed his mind that

perhaps the Stigwood organization might be interested in his

story as

well. As an afterthought, Cohn handed the story to his friend Bill

Oakes and asked him to pass it along to

Kevin McCormick, the man in charge of

film development for Robert Stigwood.

Kevin

McCormick

knew who Nik Cohn was. The two men had worked

together on the Tommy movie project. The

moment McCormick read the

story, he saw the potential.

McCormick made sure the story

reached the desk of Robert Stigwood.

Stigwood was sold from the start. Cohn's story

might be the answer to this huge John Travolta gamble he had

just taken.

|

|

SUBCHAPTER 370 -

SELLING THE STORY

|

|

After Nik Cohn finished his story, he

went to work on getting it published by Clay Felker in New York magazine.

Cohn was an aggressive guy. He could have waited to

approach Felker at work the next day, but instead he actually went to the trouble of tracking

the editor down while he and several friends ate dinner one night at a posh New York

restaurant.

Granted an audience,

Cohn told Felker his idea depicted

a

world of lower-middle-class, lower-IQ youths who lived in

Queens, Brooklyn, and the Bronx in the mid-1970s.

These teens and young adults wrapped their entire lives

around Saturday nights in the Disco clubs.

To Cohn's dismay, Felker

just laughed in his face. Ridiculous. Then

Felker rubbed it in. With Cohn standing there, Felker

embarrassed the young man by asking his dinner guests what

they thought about a story covering

the Saturday night dance rituals of young working-class

Italian-Americans.

Understandably these important

cognoscenti scoffed.

Who gives a flip about a bunch of poor kids who like to dance on Saturday

night? They had heard it before. That story was as old as

Beach Blanket Bingo, The Twist, Motown and Elvis

Presley.

Seeing the scorn on his friends' faces, Felker said forget it.

To him, Disco music was a fringe phenomenon

exclusive to boring lower-class youth.

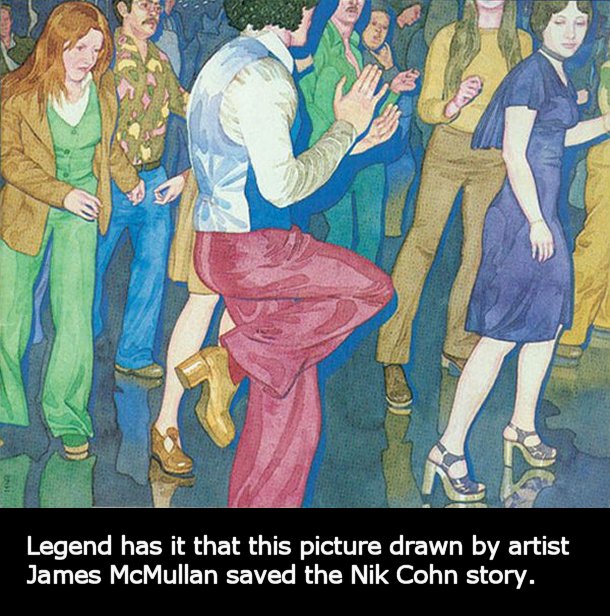

Cohn was crushed, but he wasn't going to give up easily. He

approached Felker's partner Milton Glaser who decided to

champion the story. Despite mixed feelings, Felker

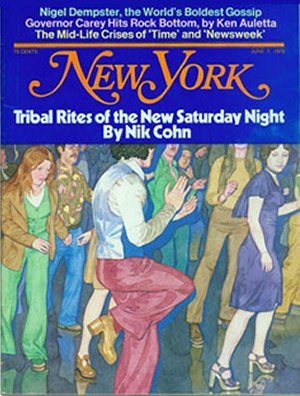

gave in and let the story run. Nik Cohn's

story, Tribal

Rites of the New Saturday Night,

was published on June 7, 1976.

|

When Robert Stigwood saw Cohn's article appear in New

York magazine, he panicked a little. He had

just signed John Travolta to a million dollar contract and

needed a movie for Travolta to star in. Stigwood had

already decided he could generate a script from Cohn's

story, so he could

not take a chance of letting the story get away.

Fearful the publicity generated by the story's appearance in

Felker's magazine could start a bidding war, Stigwood wasted

no time. Stigwood told his lawyer friend Fred Gershon that this movie

could be worth a hundred million dollars. Gershon wasn't

quite so confident, but negotiated rights to the story

nonetheless. To Gershon's surprise, Nik Cohn played

hardball. Cohn had

the touch of a gambler in him. Cohn had heard from his friend Bill Oakes

how interested Stigwood was in this story as a script

for a movie. With his confidence bolstered by inside

information, Nik the Slik raised the price.

Previously

Nik Cohn had agreed to $10,000 for an option on

his article. Kevin McCormick was already on board to

produce the movie. To Stigwood's surprise, at the last

minute another producer materialized who had heard about the story before the

Cohn deal was finalized. Gosh, too bad, suddenly the price had gone up. Gershon

smelled a rat. He suspected that Nik Cohn

was

pitching this story to every agent in town.

Sensing they were being hustled, Gershon suggested that

Stigwood back off.

Stigwood wouldn't hear of it.

He had to have this movie, so he

personally took

over the negotiations.

"I'm going to pay the kid whatever

he wants." Stigwood

nailed

the deal down by

offering Cohn first

shot at the screenplay for a guaranteed $150,000, as

well as percentage points in the soundtrack album.

Fred Gershon was

aghast. This deal was

unprecedented.

He had never heard of music

percentage points for a writer. Stigwood said this

detail was added at Nik Cohn's insistence.

Gershon could see that

Cohn had been very shrewd.

Cohn had anticipated that the soundtrack would obviously be important

to a dance movie.

Using

his own instincts plus the inside knowledge his friend Bill

Oakes unknowingly passed on, Cohn bet the farm on his Disco

story. Give the man some credit. This

incident was very likely the first time a writer

had ever gotten points

for a music album, certainly when

the property was little more than

a curious feature in a magazine.

Given the

interesting details, one might conclude Nik Cohn

was a born hustler.

Now we know why Cohn pushed Clay Felker so hard... Cohn was

in a hurry to run up the selling price of his story!

Cohn's greatest accomplishment was not the story itself, but

in getting Felker to print his story against his judgment.

Since Felker was

dead set against it, Cohn had to move mountains to get Felker

to move on his story. However, once the story was

published, Cohn was off to the races. Cohn had

the credibility he needed to raise the asking price.

Here is what is interesting.

Given Clay Felker's initial lack of enthusiasm, it is a small wonder the story ever got

published in the first place.

Even

more amazing, the story was a complete fraud!

That's right... the Tribal Rites story was a total

fabrication.

Twenty years after Saturday Night Fever came out, Nik

Cohn admitted the story which inspired the movie script was a

fraud. However Cohn swore he had a good excuse.

Cohn explained that he had run into a serious language

barrier. Raised in England, Cohn complained he could not understand a

single word the uneducated Brooklyn teenagers were saying.

Their accents and terms were such a complete mystery to him,

Cohn gave up trying to understand. He simply observed

for a while, then went home. Without any substance to

base his story on, Cohn decided to fib.

Facing a deadline, what else could he do? Cohn said he

based his story on Rebel Without a Cause.

Put on your dancing shoes, James Dean. "You're

tearing me apart!"

Believe it or not, two years later Cohn changed his story

again. This

time Cohn admitted the problem had nothing to do with the

language barrier. In reality, Cohn had never once set

foot in the nightclub. On the night he visited 2001 Odyssey,

just as the taxi pulled up, there was a fight breaking out on the

sidewalk. Cohn decided it was safer to stay in the

taxi and just watch. To his surprise, one of the fighters

lurched over to Cohn's cab and threw up. With that, Cohn

told the driver to get him the hell out of there.

As they drove

away, Cohn caught a glimpse of a tall, confident figure

standing in the club doorway. Dressed in flared

crimson pants and a black body shirt, the man was coolly

surveying the action. Cohn was impressed by the man's

aloof demeanor. There was a special quality to this

mysterious figure

as if he was operating on a different plane from the rest. On

the spot, Cohn had his hero.

He

wrote a completely fictional story using

2001 Odyssey as his location and the unknown

figure in the doorway as his star.

Cohn had once hung around a charismatic street hustler named

Chris at a spot called Shepherd's Bush in London.

Basing his Disco hero on Chris, Cohn worked from there.

When Cohn was

finished, he added a note that insisted 'everything in

this article is factual.'

That, my

friends, is the very definition of chutzpah.

Yes, sad to say, there

was no real-life Tony Manero. Just add Tony Manero to the list of

Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny and tooth fairy fibs.

Yes, indeed, Nik Cohn pulled off one of the great scams in

literary history.

By lying through his teeth, Cohn parlayed a 15-page short story into

a small fortune. For the rest of his life, every time

someone bought a Saturday Night Fever album,

Cohn would hear the joyful ring of ka-ching, ka-ching. There were countless other perks as well. As a reward, Nik Cohn got to hang out with the biggest stars

and attend premieres with beautiful singers draped on his

arm. Not bad, huh?

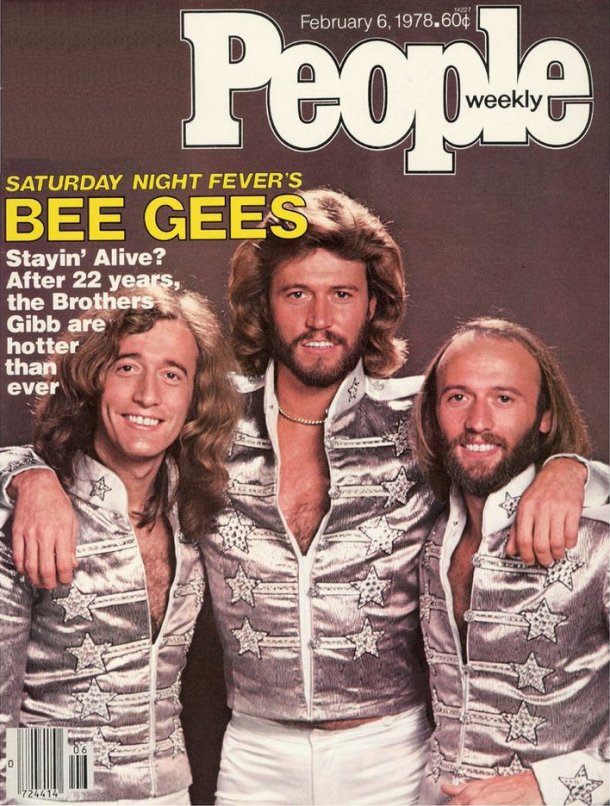

|

SUBCHAPTER 371 -

the bee gees

|

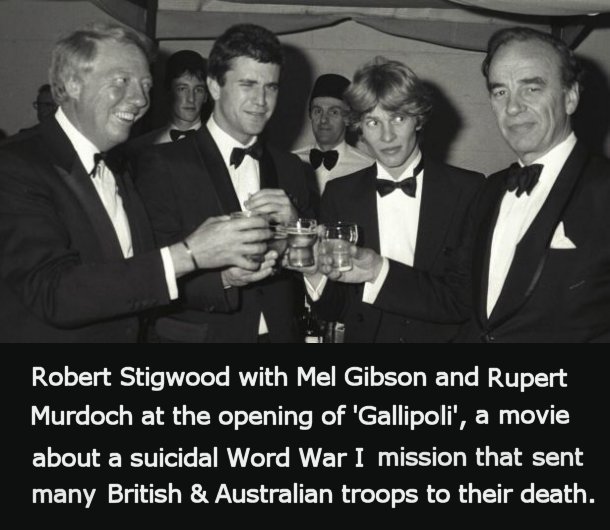

Robert Stigwood had the magic touch. He parlayed his early success in the music

industry into ambitious productions on stage and in film.

Stigwood learned early on to mix music with drama.

Nearly every one of his productions involved music.

Among Stigwood's stage credits were

Tommy,

Evita,

Sweeney Todd, Hair,

Pippin,

Oh Calcutta and

Jesus Christ Superstar.

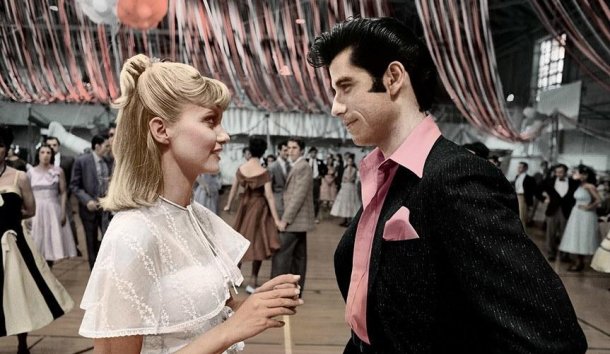

His movie credits would include Grease,

Tommy,

Gallipolli, and Jesus Christ Superstar

as well as Sgt. Pepper's

Lonely Hearts Club Band, a musical extravaganza.

Stigwood's main passion was to do Grease, the

exciting 1971 Broadway musical. By a twist of fate, Stigwood's

efforts to bring Grease to screen would accidentally

lead him to produce his most famous project, Saturday

Night Fever.

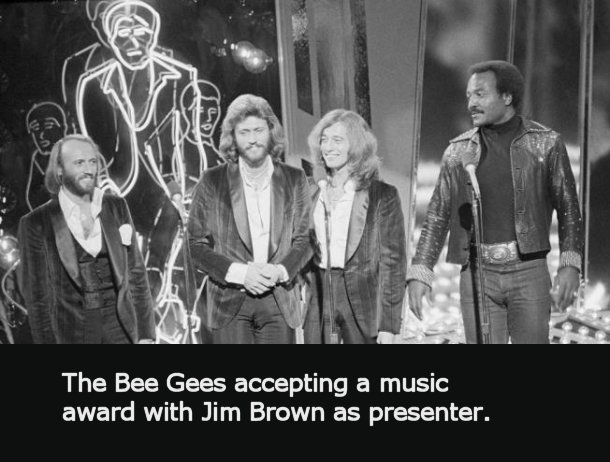

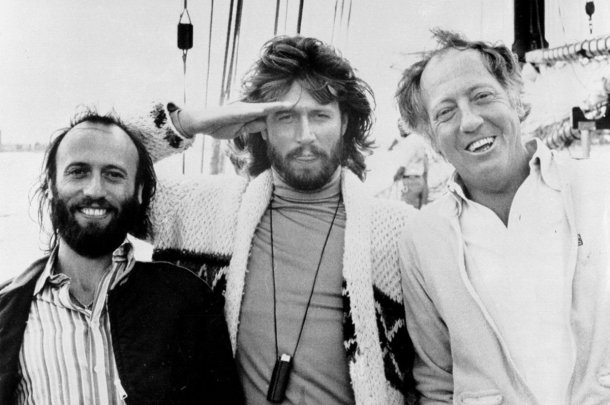

The Bee Gees were an

Australian rock group that consisted of three brothers,

Barry, Robin, and Maurice Gibb. The Bee Gees had

gotten their start in the late Sixties. With

Robert Stigwood as their manager, the

group quickly scored some initial hits such as 'To

Love Somebody', 1967.

Thanks to their instant success,

the Bee Gees were said to be the next Beatles.

However, they fizzled almost as fast as they sizzled.

You know the story... drugs, booze, distractions. By

the time the mid-Seventies rolled around, the Bee Gees were

toast. As of 1974, the Bee Gees were

being referred to in the past tense. Rumor had it they were

washed-up has-beens.

Fortunately Stigwood had enduring

faith in the Bee Gees. Stigwood

had a real soft spot for these guys. They were

always his pet project. The problem was that once

a rock band loses its momentum, it is difficult to

regain it. On the other hand, one good hit is all

it takes to get back on top. Easier said than

done. The Bee Gees were terrific

songwriters, but they had not had a major hit in years.

Their music consisted of gentle ballads at a time when

Hard Rock was the dominant sound.

It didn't look good for the Bee

Gees, but Stigwood stayed by their side.

Telling the three brothers he believed in them,

Stigwood encouraged them to keep writing songs. "You

know what they say. The harder you work, the luckier you

get."

After assuring his friends that

sooner or later their luck would turn, Stigwood had a

suggestion. Why not move away from ballads, the

Bee Gees staple, and take advantage of the growing

American interest in dance tracks? Good idea.

The Bee Gees moved to Miami and began experimenting.

In 1975, they crafted a

dance-oriented Disco song titled Jive Talkin'.

To their surprise, it became their first #1 hit in four

years. Jive Talkin' started their

comeback. The band liked their new sound, so they

stayed with it. You Should Be Dancing

was released released in 1976. It quickly became their

second dance track to hit #1. The Bee Gees were

back.

Robert

Stigwood was pleased his suggestion had worked out so

well. At the same time, he was very surprised at the

amount of interest in this unorthodox dance music.

Disco music was hardly his cup of tea, but Stigwood

understood that success in this business was

unpredictable and difficult to attain. His advice

was if it works, stick with it.

The script for

Saturday

Night Fever

appeared on Stigwood's desk out of nowhere. It was 'Luck', a wonderful,

serendipitous accident

so to speak. The moment he saw the word 'Disco',

one can imagine Stigwood's fondness for the Bee Gees played a major

role in his snap decision to pursue the SNF

project.

However, as we shall see, it turns out that Fate was about

to throw a major curveball into Robert Stigwood's plans.

When it came time to create the movie soundtrack, the Bee

Gees were unavailable. Stigwood went absolutely

apoplectic!

|

|

SUBCHAPTER 372 -

JOHN TRAVOLTA

|

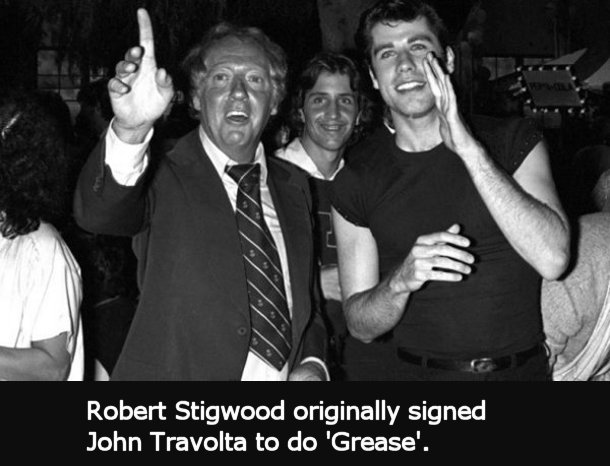

Robert Stigwood

was kind of a lucky guy, but he also possessed considerable talent

and instinct. His 1976

decision to sign John

Travolta to a three-movie deal was sheer genius.

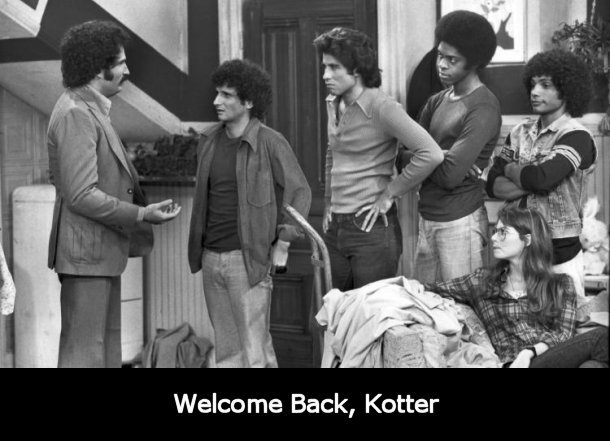

Welcome

Back, Kotter was a 1975 television sensation.

The show was based on a sarcastic, street-smart high

school teacher who takes a group of incorrigible yet

loveable teenagers under his wing and attempts to show them the light.

From the start,

John Travolta was the undeniable break-out star of the

show. However, he was not without his critics.

Some suggested Travolta couldn't act his way out of a paper bag. Ironically,

since Travolta was a high school dropout, it was

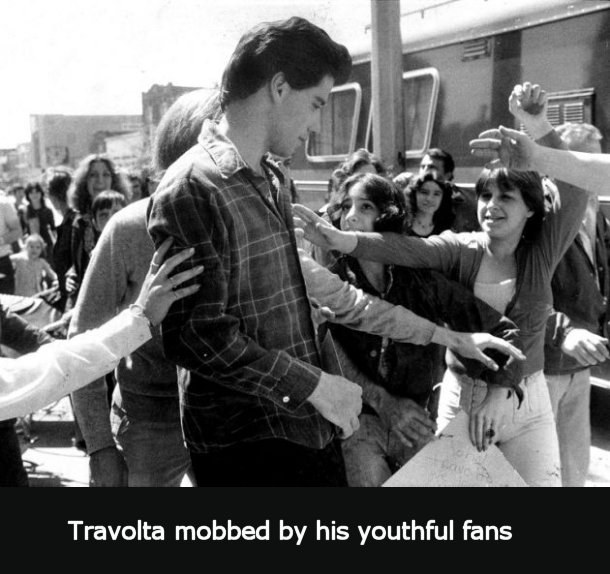

said he was just playing himself. Maybe so, but his popularity was off the charts.

Travolta could not go out in public without being mobbed.

By the second season, Travolta was receiving more than

10,000 fan letters a week.

Stigwood had to

have him! Producer Stigwood was so convinced of

Travolta's star potential that he had just placed a million

dollar bet on this young TV heartthrob. What

was Robert Stigwood thinking? A million dollar

contract for some kid with no longevity, no track record?

The insiders

thought Stigwood had gone nuts. In the history of

television, no one had ever successfully made the transition from TV

star to movie star. Many had tried, no one had won. Therefore the idea of paying a

million bucks to an untested actor was quite a stretch,

especially since many assumed that Travolta was no more

talented than Vinnie Barbarino, his dumb but sexy TV character.

Fortunately, Stigwood was privy to

something others were not aware

of. Stigwood had been a fan of Travolta

well before Welcome Back, Kotter.

Back in 1971, Stigwood had auditioned Travolta for the lead

in Jesus Christ Superstar.

Although Stigwood noticed Travolta had

oodles upon oodles of talent, there was

one problem... Travolta was 17, much too young

for the part.

Nevertheless, Stigwood penciled a note on a

yellow pad: “This kid will be a very big star someday.”

Around the same

time as Travolta's youthful audition, Stigwood had his eye on something else: Grease.

Stigwood was a huge admirer of the musical that

debuted in 1971. Based on a

hunch, Stigwood had taken out an option on Grease.

He planned to make it a movie after the play ran its course.

When Stigwood saw Travolta

on TV, he

immediately visualized Travolta as a great fit for the

movie version of Grease. Now that Travolta

had confirmed Stigwood's initial instincts with his Kotter

breakout, Stigwood decided to lock the kid up to do Grease before

his price

tag climbed any higher. Stigwood was convinced that Grease

was the perfect vehicle for the cocky teen heartthrob.

Then came the bad news. Grease

was off-limits! Uh oh. There was a clause in the contract for Grease

that said Stigwood's option would have to wait until 1978 in case the musical was still going strong.

Was Grease still going strong in 1976?

You betcha. It was Stigwood's bad luck to take out an

option on the longest running play in Broadway history.

No problem. Stigwood assumed for a little cash, the producers would let

him start filming sooner than the contract stipulated. Wrong. The producers refused to let Stigwood proceed early.

Stigwood was heartsick. He had signed

Travolta based on the gamble that Grease would be available

soon. It was 1976 and he would

have to wait until 1978 like the option said. To wait

two years was utter madness. Travolta was hot right now!

This was serious bad luck. Or was it? Stigwood

certainly thought so. However, anyone familiar with

Fate knows that sometimes bad luck has a

way of turning into good luck.

In this case Stigwood's ambitions were rescued when Nik Cohn's

Disco

story appeared on his desk out of nowhere.

Stigwood quickly

realized that Cohn's

story would be perfect for Travolta's talents.

Now wasn't that a nice little coincidence??

It almost makes you wonder if Fate was involved.

|

|

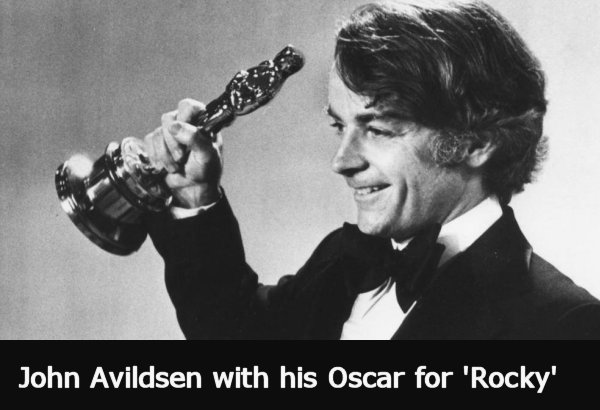

SUBCHAPTER 373 -

JOHN AVILDSEN AND

NORMAN WEXLER

|

| |

It was late in 1976. Robert Stigwood was in a serious hurry to take

advantage of the timely appearance of Cohn's story vis-à-vis

Travolta's expensive new contract. To Stigwood's surprise, the talented,

but controversial John Avildsen

was available. Avildsen was best known for making the

sleeper hit Joe. Produced on a tight

budget of only $100,000, Joe grossed over $20

million box office, making it the 13th highest-grossing film

of 1970.

Stigwood had wondered why a director of Avildsen's

caliber and track record was available. Was Stigwood missing something?

He checked around and discovered Avildsen had been fired as

the director of Serpico, a movie with Al

Pacino that was a surefire hit.

A keen observer of talent,

Stigwood could see Avildsen was

abundantly gifted. However, Stigwood knew full well he was taking a risk with the

temperamental director

by considering him.

Stigwood decided to bring Avildsen in for an interview.

Avildsen said if Stigwood had misgivings, why not take a

look at Rocky, his most recent project.

At the time, Rocky was a couple month's away from being

released in December. After

seeing a rough cut of

Rocky, Stigwood

was impressed. Rocky was a movie about

an underdog who succeeds against all odds. Ditto the

Travolta character. In addition, Avildsen had a track

record of turning sleeper movies into hits. Ditto

Saturday Night Fever. Figuring Avildsen

could do the same thing for the inexperienced Travolta that he did for

Sylvester Stallone, Stigwood hired Avildsen on the spot.

|

Big mistake.

Almost from the start Stigwood regretted

taking a chance on Avildsen. To begin with, the temperamental director

quickly

insisted on hiring a temperamental writer. Avildsen

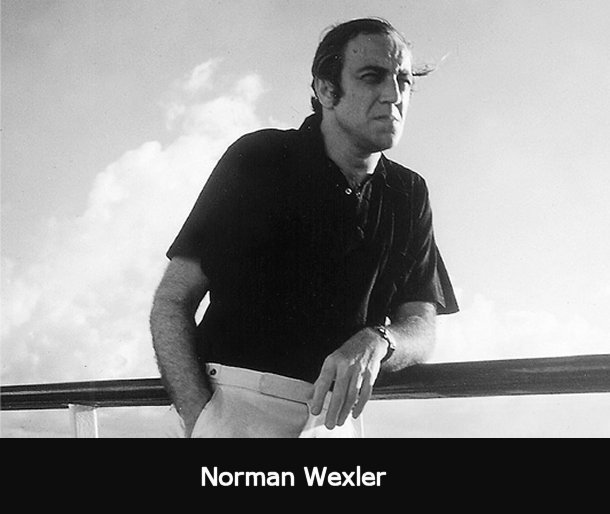

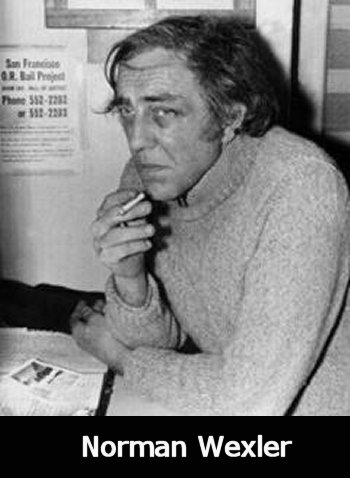

wanted screenwriter

Norman Wexler.

Not so fast, Stigwood

said.

Nik Cohn

was already working on the script.

Besides, if this Wexler

guy was so good, then why was he available? "Because

Norman Wexler is a madman."

Stigwood raised an eyebrow. "Why

should I hire a madman?"

Avildsen replied, "Because he's a genius."

Avildsen explained that Norman

Wexler's screenplay for Joe had received an Oscar

nomination for Best Original Screenplay. Then he added

that Wexler's screenplay for Serpico

received an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

Did Stigwood want his movie to rest on the talents of an

amateur with a 15 page magazine story or hire a proven

talent?

Good point. Stigwood said he would reconsider his decision.

No one

in the industry would touch Wexler, but Stigwood

decided to roll the dice. Wexler was not only a

genius, he was desperate for work due to his bad reputation. Stigwood had a

hunch Wexler was likely to pour his

soul into the project and he was right. Wexler's script was so brilliant one can ask if his own pain gave him

added

insight.

Wexler captured the bleak lives of the

oft-struggling Brooklyn street kids far too well.

|

|

Avildsen was right about the genius part, but he was also

right about the madman part. Wexler was a real-life Jekyll and

Hyde. A Harvard graduate with an IQ of 180, Wexler had

done brilliant work on Serpico, a truly

superior movie. At the same time, his psychosis made

him fearless with delusional grandeur. Wexler was a vicious,

vindictive paranoid who was shockingly uninhibited.

Throughout the filming, Norman Wexler terrorized various

people on the set with his antics. When Wexler was off

his medication, he could turn very aggressive. One day

Wexler showed one of the female extras the .32 caliber

pistol he was carrying. He was trying to impress the

woman, but it had the exact opposite effect. However,

there was a silver lining.

No one gave

Norman Wexler the slightest bit of trouble after that. No

one dared to disagree with Wexler on the slightest script

issue. With his script left untouched by lesser

talents, Wexler's brilliant screenplay raised Nik Cohn's

humble efforts to amazing new heights.

Meanwhile, Robert Stigwood had growing

doubts about

his

director.

Rocky had just been

released and Avildsen was getting a ton of positive press.

Perhaps Avildsen's success with Rocky had gone to his

head because he was getting John Travolta confused with Sylvester Stallone. Taking a

page out of West Side Story,

Avildsen told Stigwood he wanted to use Travolta for a big fight scene inside the club. Avildsen's vision was some sort of

rumble straight out of West Side Story, the Disco version of Sharks versus Jets. Stigwood's assistant Kevin McCormick tried to explain this was a different kind of movie,

but Avildsen was adamant.

Trying his best to be patient with the volatile director, McCormick offered a compromise. Why not let some of the extras have the fight if it was that

important?

Avildsen wouldn't listen. It had to

be Travolta throwing the punches. No one else would

do. McCormick asked the writer Wexler what he thought.

When Wexler said the fight was not consistent with Travolta's

standoffish character, McCormick put his foot down and

said no.

Angry at Wexler for not backing him, Avildsen

pointed out that Wexler was

insane. What did Wexler know? To Avildsen,

Wexler's disloyalty justified bringing in a

third writer.

McCormick said no to that too, giving Avildsen the 'too many

cooks' cliché. However McCormick's logic went right over the

prima donna director's head.

Avildsen put his foot down and implored Stigwood to back him

up. Now Saturday Night Fever had three writers.

Avildsen's next move was to irritate

John

Travolta. He decided Travolta

was a rotten dancer, physically soft and way too fat.

He told Travolta to lose 20 pounds

and find some muscles.

If you're going to act like a stud, try looking like one. When Travolta didn't move fast enough to please Avildsen, he brought in Sylvester Stallone's

Rocky trainer to

accomplish the feat.

Although Travolta was incredibly insulted

by Avildsen's blunt criticism,

to his credit, the actor decided to cooperate.

The final straw was the music.

This was a movie about music and dancing. They were about

to film, but there

was no music.

Everyone noticed the problem, but they were so frightened of

John Avildsen, they kept their mouths shut.

What was

the hold-up? Where were the Bee Gees like Stigwood had

insisted?

Indeed, John Avildsen had been told to line up the Bee Gees, but

had ignored

the suggestion so far. Why was this? Because Avildsen could not stand the Bee Gees!

To begin with, Avildsen considered the Bee Gees to be washed up has-beens.

Furthermore he

couldn't stand grown men singing in falsetto.

So far, Avildsen had chosen to disobey what was more or less a

direct order to hire the Bee Gees. Not only that, he

hadn't told anyone of his decision.

So here they were, ready to begin

filming, and there was absolutely no soundtrack and no Bee

Gees. The timing of this crisis could not have been

worse.

Stigwood was nowhere to be

seen. During the

pre-filming stage, he was preoccupied trying to

sign the Rolling Stones to his record

label.

|

Somebody on the

Rolling Stones side of the negotiations was getting very

greedy. Stiggy was sick of dealing

with Piggy, so he walked

away from the deal. On the

return flight to New York,

Stigwood was still really irritated over the blown

deal.

So was Stigwood in a good mood upon his

return?

Uh, probably not.

Now his mood was about to get

worse. Much worse.

As we recall, Stigwood

had two reasons to pay extra for the rights to Nik

Cohn's story. First, he had John Travolta on board and

needed a vehicle immediately. Second, the Bee

Gees were Stigwood's pet project. Indeed, Stigwood had

embarked on the SNF project specifically to help assist the Bee

Gees with their new Disco music career.

For more than ten years Stigwood had directed their management, their record label,

and their music publishing rights. Furthermore, Stigwood had personally overseen the

Bee Gees' comeback by recommending they concentrate on Disco dance

tunes. Stigwood was

so close to these three young men he felt like they were his

own kids.

|

|

Therefore getting his protégés on board

for the movie was a foregone conclusion. Too bad no

one bothered to tell the Bee Gees.

When Stigwood learned that Avildsen had

refused to contact the Bee Gees, he blew his top. Screaming at the top of his lungs,

Stigwood called

Avildsen into

his office for a meeting and

demanded an explanation.

Avildsen did not back down. First

he told Stigwood he could not stand the Bee Gees. Then

he called the Bee Gees a

bunch of washed-up white guys who sounded like teenage girls

when they sang. Stigwood nearly had a stroke.

That is when something very strange

happened. Very strange indeed. Just as the arguing reached a

fever pitch, the telephone

rang. It was Fate calling.

Stigwood

answered it himself and started to smile.

Grinning, Stigwood turned to Avildsen.

"Well, John, guess what? I have

good news and

I have bad

news. The good news is that you have just been

nominated for an Academy Award for

directing Rocky.

Congratulations! The bad news is that

you're fired."

|

|

SUBCHAPTER 374 -

dumb luck

|

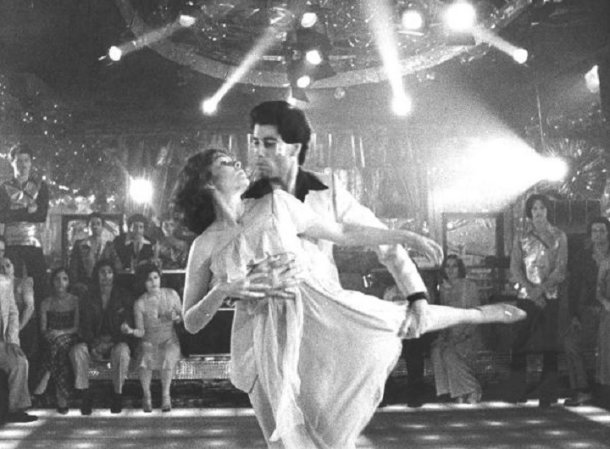

John Badham was

hired to take Avildsen's place. However, amidst the chaos of this

change on the eve of filming, everyone seemed to forget there was still no music chosen

for the film.

One day

as Travolta was

doing dance rehearsals, someone

put on the Bee Gees song 'You Should Be Dancing,'

a hit which had

been released the previous year.

Travolta said, 'Hey, that's a pretty good song.

Nice beat. Why don't you see if these Bee Gee guys have any other songs?'

When Stigwood heard what Travolta had said, he had a major panic

attack. Despite his direct orders, Stigwood was

astonished to find the Bee Gees had

still not been contacted!

Imagine how Stigwood felt upon

learning

that the Bee Gees

were completely in

the dark regarding this project. So far no one had agreed on a single song for the

movie. Stigwood was staring at a Musical without

Music. This was worse than the Sound of Music

without Edelweiss or Do-Re-Mi.

His heart racing, Stigwood immediately got on the phone.

He reached the Bee Gees who were occupying a chateau in

northern France. They were busy mixing a live

album. They had never even heard of

Saturday Night Fever.

"So, Stiggy, this is a big surprise. Tell us about

your movie."

Stigwood told the Gibb

brothers that the

song You Should Be Dancing

was great and that Travolta liked it.

Then he

told them a little bit about the movie... it was a

low-budget

film with

Travolta playing

the

cocky but aloof dance stud surrounded by countless adoring women. Then Stigwood got to the

point and asked the guys if they

had any other

songs they could contribute. Or

if they felt like it, maybe they could write the entire

soundtrack.

The three brothers were fairly shocked.

This request was completely out of the blue, but better

later than never. After all, this was Stiggy, their

patron, their compadre. So they quickly signed

on, right? WRONG.

The Bee Gees looked at each other and nodded, 'No way,

we're busy, forget it!'

Feeling a bit guilty, the brothers spoke up.

'Look, Stiggy,

you can't just ring us up and expect us to drop

everything we're doing. You know damn well we

can't just snap our fingers and pull a hit song out of

thin air. Besides, we have our own

album to do.

We're sorry, but

we don't have the time to sit down and write

music for your

film.'

With regret,

Stigwood said he understood and hung up. Stigwood

was at a complete loss. What was he going to do

without the Bee Gees? Stigwood wasn't mad at the brothers, but it hurt

to know he had taken on this project to help

them only to see this invaluable opportunity go to waste.

Meanwhile,

the brothers kicked it around after the call. Barry pointed

out that Stigwood had been their friend through thick and

thin. When things were rough, Stigwood believed

in them.

They all started to nod. It was true, Stiggy had always

been there even when they totally screwed up their career.

With their conscience prodding them in the right direction, the brothers

changed their mind. In an extraordinary show of

loyalty, the

Gibb brothers stopped what they were doing and began to work

'feverishly' on this

unexpected project.

The thing is,

the Bee Gee's sudden change of heart wasn't ordinary luck,

this was what one would call 'Dumb Luck'. Everyone had dropped the

ball on the Bee Gees and yet at the very last minute,

Stigwood got his guys on board with his desperate

SOS plea. What happened

next was

insane. Once they got started,

their imaginations were on

fire!!

The

three brothers wrote five songs in one weekend, every one

them destined to be future mega-hits.

•

Staying Alive

•

How Deep is

Your Love?

•

Night Fever

•

More

Than a Woman

•

If I Can't Have You

In addition, the

Bee Gees decided their two previous dance hits,

Jive

Talkin' and You Should Be Dancing,

should be included.

One week after

the phone call, Barry Gibb handed Stigwood seven dance tracks.

The Bee Gees were now the featured artists on the upcoming

SNF music album.

Destiny was breaking right for the

Bee Gees.

Despite having no idea how their music would be used,

these

catchy songs would lead to an amazing comeback in their

career. Thanks to their

uncanny burst of creativity, the Bee Gees would become

the hottest group on the planet. Ah, Fate and its

twists and turns.

As we now know,

the music from Saturday Night Fever became

the best-selling soundtrack album of all time.

The

Bee Gees were rewarded beyond their wildest dreams when their

songs made

music history. Not bad for a last-minute

weekend effort.

|

|

SUBCHAPTER 375 -

SUPERSTAR

|

| |

|

Every once in a

while a movie comes along that no one expects much

from, but it becomes special anyway. Most people

point to Casablanca as the best example. In a

similar fashion,

Saturday Night Fever

became a classic as well. Despite low expectations for

Stigwood’s scrappy,

low-budget

Disco movie, this hard-hitting story of directionless youth

with John Travolta as the Dancing James Dean packed quite a punch.

By now, it is

clear that Robert Stigwood caught one lucky break

after another with Saturday Night Fever.

The perfect timing of Nik Cohn's story, Norman

Wexler's script, and the mystical ability of the Bee

Gees to write five smash hits in one weekend all

suggest there was a special light shining on this

project.

Some people say

Stigwood's most incredible break of all had to be

the inclusion of John Travolta. Wrong.

This was not luck. Give the man

some credit. Robert Stigwood was the guy

everyone in the industry laughed at for handing 'Vinnie Barbarino' a million

dollars. Who's laughing now?

Not only did

Stigwood see Travolta's

potential right from the start, he also saw

the potential of Grease to be a

mega-hit movie seven years in advance. Convinced the pairing of Travolta and Grease

would be box-office magic, history has shown Stigwood's instincts were right on the money.

To date, Grease has earned $400

million and still counting.

However, we

also know the major reason that Grease

did so well was its ability to tap into the momentum

created by John Travolta's sensational performance in Saturday

Night Fever. It was uncanny how

Travolta was tailor-made for the role as the cocky, yet moody dance stud.

Actress Dinah Manoff had this to say

about her fellow actor.

"There was an energy surrounding John unlike anything I

had ever experienced. It wasn’t even lusting

on my part.

It was being in the presence of something epic. I

had never been around a charisma that was at its peak

that way. I cannot describe it to you. There

is no other movie star I have ever been around who

carried the energy John did in those days with

Grease and Fever. And the funny

thing is that John didn't even know how good he was.”

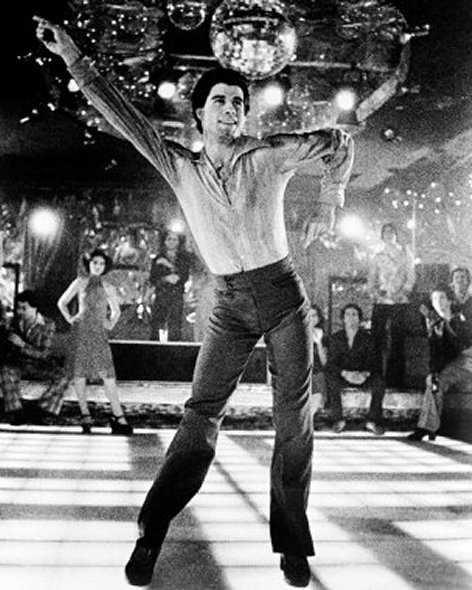

Saturday

Night Fever

changed John Travolta’s life.

Travolta was wonderful as the ambitious young man who yearned to make

something of himself. Thanks to his performance,

Saturday Night Fever struck

a chord with audiences all over the world.

What Marlon Brando and James Dean

were to the Fifties and Mick Jagger and Jim Morrison were to the Sixties,

John Travolta

achieved equal status in the Seventies.

Saturday

Night Fever gave the decade its cultural identity and John

Travolta became a pop culture icon. For this moment in

time, John Travolta was the brightest star in the

galaxy.

|

|

SUBCHAPTER 376

-

OBSERVATION

49

|

Rick Archer's Footnote:

Like Magic, everything came together for Robert Stigwood.

A powerful story, a gifted actor, and the inspired music fit

together so perfectly that one might actually be tempted to give the

concept of 'Synchronicity' a closer look.

Synchronicity is

a term synonymous

with 'meaningful coincidence'. To believe in

Synchronicity is to believe the old saying there are

no accidents. Not everyone agrees with this

far-fetched idea.

Synchronicity is one of those mumbo jumbo terms like

esp, mojo, sixth sense and voodoo

that skeptics relegate to the dustbin of pseudoscience.

So is there any

reason to believe in Synchronicity? Good question.

In my

opinion, the easiest way to make a case for

Synchronicity is to point a finger at

Saturday Night Fever.

|

|

Not much was

expected from this movie.

Keep in mind this tale was supposed to be a low-budget

throwaway project. All Stigwood was trying to do was

keep Travolta busy until Grease became

available. And yet by complete accident, Stigwood was

able

to

hit a gold mine with Saturday Night Fever because he

caught

three talents... Travolta, Bee Gees, and Wexler... at the

absolute hungriest part of their careers. Working

together, Stigwood and his talented men came up with

something transcendent.

People ask if anyone knew in advance how special the

movie was going to be.

Bill Oakes, right

hand man to Robert Stigwood, said his boss was certain

this was going to be a big hit, but he was the only one with

that kind of confidence. To everyone

else at Paramount,

the success of Saturday Night Fever

came as a huge surprise. Before the release, the smart-ass

muckamucks at Paramount thought the movie was

a joke.

Oakes was especially resentful of their

condescending attitude.

"Paramount didn't care

a lick about our movie. They gave

us an office on the lot the size of a broom closet and

called Saturday Night Fever the studio's 'little disco

movie'. I could not stand that phrase.

Senior executives for Paramount would visit

the Fever set. They would snoop around,

complain about this or that, then ask

disparagingly, "Well,

Billy Boy, how's

your little disco movie doing?"

|

|

Oakes claimed that Robert Stigwood was certain the movie was

going to be a hit. One might ask if Stigwood had a

sixth sense about this project. After all, the Nik

Cohn story appeared out of thin air the same moment Stigwood

got the bad news about Grease being

unavailable. Talk about a good omen. I suppose

if something is meant to be, you are bound to get some lucky

breaks.

Stigwood was so lucky that even his mistakes worked in his

favor. Say what

you will about Director John Avildsen, the man Stigwood

fired. Avildsen was wrong

about the Bee Gees, but he was right about a lot of other

things. For example,

Avildsen told John Travolta that he was fat and couldn't dance a

lick. Deeply offended, Travolta worked his butt off to

prove Avildsen wrong. Without Avildsen's prodding,

would Travolta have given as good a performance?

Avildsen's criticism of the movie script was crucial to the

success of the movie. Nik Cohn

had written a fairy tale off the top of his head, then

insisted he be allowed to write the movie script as part of his

deal.

However, Cohn had no experience at

writing a movie script. Stigwood was fortunate that

Avildsen recognized the limitations of Cohn's work.

Avildsen

insisted on hiring Norman Wexler over Stigwood's strenuous objections.

What a lucky break! Wacko Wexler

took Cohn's fake 15-page magazine story and breathed life into

it.

Norman Wexler gave this

low-budget movie a truly extraordinary script. His

work was so good that Wexler won the 1977 Writers Guild of

America Award for Best Original Screenplay. Meanwhile

the disgraced director John Avildsen was given absolutely no

credit whatsoever. This is very ironic because without

Avildsen's competence, the movie might have flopped.

|

In the years to follow,

Saturday Night

Fever was credited with

kicking off the Disco Era, but

the truth was more complicated than that. Back in 1976,

the

'Suits'

thought the whole thing was rather

silly because the timing was wrong.

They believed Disco had run its course.

Actually, there was some credibility to

that sentiment.

When Nik Cohn's article appeared in

New York

magazine, many in the music industry believed that

Disco music with its

repetitive electronic background and vapid lyrics was on

the way

out. People in the know said Disco was trending down.

What the movie

did was breathe

new life into a dying genre.

Saturday Night Fever

did not jump on a swelling bandwagon, but rather resuscitated

something on its way out. So in that sense, SNF

really did create the Disco Era. Or perhaps we

should call it 'Act Two'. Thanks to the movie

and its soundtrack, Disco achieved more widespread,

mainstream, middle-America success than it ever had before.

Although 'Luck'

was a major factor, there was clearly a great amount of

skill involved as well. Another smart move

Robert Stigwood made

was to release the soundtrack

before the film's debut. This strategy was both

innovative and brilliant. No soundtrack had ever been

released in advance before. There is an anecdote that bears out the effectiveness of

Stigwood's

move. Michael Eisner, head of production at

Paramount, was skiing in Vail, Colorado, in December two weeks before

the movie opened.

"I

heard Staying Alive at the bottom of the

ski lift. Then it was playing at the top of the lift.

I heard it again in the restaurant at the top of the

mountain.

Something was definitely going on, so I called my

boss Barry Diller, head of Paramount. I said, "Barry,

everywhere I go, I hear the music. What do you think? Do we have a hit here?"

Then the movie opened. Travolta was the biggest

damn

thing that ever happened. In the first 11 weeks,

the movie made $11 million. Over time, it would

gross $285 million. The soundtrack was not only

the best-selling soundtrack of all time, it would hold

the record for 14 years, an eternity in this business.

Someone really knew what they were doing with this

music."

|

|

They always say that when you're hot, you're hot.

Robert Stigwood clearly

had the Midas Touch.

Everything he touched turned to gold. The

last-minute inclusion of the Bee Gee music was just one of

many 'dumb lucky' breaks for Stigwood.

"Someone really knew

what they were doing with this music..."

Oh boy, they sure did know what they were doing with the

music, didn't they? Let's go ahead and wait till the

movie is nearly done with the filming,

then call the Bee Gees.

Thank goodness it all worked out. Due to Stigwood's gut-feeling about his boys,

Saturday Night Fever

revived the career of the Bee Gees.

Their

original music score anchored

the

best-selling movie soundtrack album of all time.

And the box office?

Saturday Night Fever would go on to gross $285 million.

Its combined box office and soundtrack sales would make it

one of the most lucrative films in history.

Lost in

all the hoopla was the original budget... $3.5 million.

Considering the importance Saturday Night Fever

had on my life, I studied

Robert Stigwood with intense curiosity.

How do successful people become successful? In Stigwood's case, it was obvious that

he had a keen eye for talent.

Another

characteristic was Stigwood's willingness to

bet on his own instincts. Of course talent and

original ideas are a prerequisite to success.

However, often the difference

between a successful person and an unknown is the courage one

musters to take a calculated risk and bet on

one's ideas.

I could not escape the feeling that Stigwood was Lucky.

In fact, I am

surprised at the number of successful people who cite 'Luck' as a major

factor. Many tales of successful people involve being

in the right place at the right time. Thanks to a

lucky break, they were chosen for a position ahead of

other people who were just as talented and just as ambitious.

To me, the story of

Robert Stigwood is pure Fate. At this

one magic time in his life, everything turned to Gold.

Even when Stigwood screwed up... John Avildsen and the Bee Gees story

for example... things worked out to perfection.

The way I see it, someone up there liked Robert Stigwood.

To me, the

funniest aspect of all is that the entire phenomenon started

on a fake story. Without

Slick Nik and his brazen nerve to pass off a fairy tale as

the Real Thing, Disco would be little more than a footnote

as silly music from the Seventies. There

would be no Bee Gees megahits, no Travolta

superstardom, no Disco acrobatics, and no nostalgic Disco parties

complete with ugly clothes, bad jokes and crazy hair styles.

All this because some English stiff made up a wild yarn and

sold it as truth. Barry

Gibb once said to Nik Cohn, “This is all your bloody fault, isn’t it?” Cohn

just nodded.

I don't approve of Cohn's methods, but Nik the Slick was

clearly Destined to play a major role in this unusual story.

Nik Cohn definitely got lucky. But you know what?

So did a lot of people! Stigwood, Travolta,

Cohn, Wexler, the Bee Gees to name a few. Throughout the

behind-the-scenes story

of Fever, I got the feeling

that everyone involved suddenly became much smarter and more

creative than at any other time in their

life. 5 hits songs in one weekend!

Best screenplay of his life! 'It was like being

in the presence of something epic. I had never been

around a charisma that was at its peak that way.'

Everyone was at the top of their game. Using a

sports cliché, it was a career year for everyone.

The way Fever worked out so perfectly defies

the imagination. In fact, so many things clicked, one

might believe Robert Stigwood had the Wheel of Fortune spinning in his direction

and brought everyone else along for the ride. Do you believe in

Synchronicity yet?

|

|

|

MAGIC CARPET RIDE, PART

TWO

Chapter

EIGHTY EIGHT:

CROSSROAD

|

|

Rick Archer's Note:

As we know, a year and a

half after Saturday Night Fever, Travolta went on to

film Grease. This became a second mega-hit

collaboration between Robert Stigwood and John Travolta. But

what about the mysterious third movie that the original three-movie

contract called for? I knew you would be curious, so I grabbed

a segment from Chapter 178 of Magic Carpet Ride to

satisfy your curiosity.

I hope you enjoyed

reading my story as much as I did researching it.

|

SUBCHAPTER 781

- A QUIRK OF FATE

|

To make

a long story short, John Travolta had to beg the

Movie Moguls to let

him be in Urban Cowboy. That is hard

to believe, but it is true. It all

went back to the contract Travolta had signed with

Robert Stigwood. The contract called for

Travolta to do three movies.

-

Saturday

Night Fever

-

Grease

- And, uh,

yeah, that third Stigwood blockbuster.

Out of

curiosity, can you name

John Travolta's third Stigwood movie? If

you are stumped, don't feel bad. I drew a

compete blank and I bet you will too. The odds

of getting it right are slim and none. But if

you succeed, I definitely want you on my Movie

Trivia team.

One

reason no one remembers Travolta's third Stigwood movie is because apparently no one

ever saw it. Well, maybe a few people saw it, but they won't

admit it. Okay, either you know the answer or

you don't care or you've finished looking it up on Google.

Either

way, let's get to it.

|

|

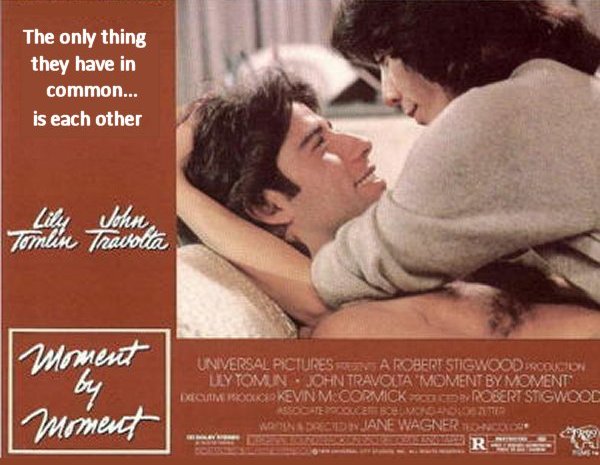

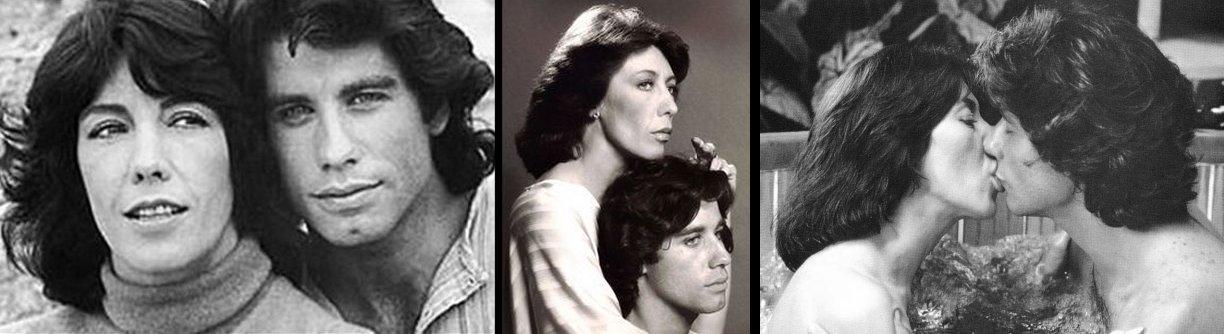

Moment by

Moment

(1978) with Lily Tomlin was Travolta's third

Stigwood movie. This movie was an unmitigated flop.

'The

only thing they have in common is each other.'

What utter

nonsense.

They had

NOTHING IN COMMON. Any two people off the street reading

lines from the script would have been more effective. Cast as a 'May-December'

romance, Tomlin and Travolta were mismatched stars

from the start. They had the worst chemistry

in cinematic history. Tomlin did not click at

all as Travolta's cougar girlfriend. No

sizzle, just fizzle.

However, the

thing that catapulted this flick from mere flop to

catastrophic failure was an unanticipated bad break.

Lily Tomlin bore an uncanny resemblance to Travolta

in both facial structure and body type. Making

matters worse, their matching hair styles made the

weird resemblance impossible to miss.

On screen,

Tomlin looked more like Travolta's mother than his

girlfriend.

It did not help that Tomlin was 16 years older, thus

making the mother-son connection a biological

possibility.

The moment

their icky hot tub scene screamed 'Incest!',

everyone in the theater got a bad case of the

heebie-jeebies. The movie was so creepy,

droves of people got up and left.

|

Here is the problem. The moment you look at the

pictures and think 'Mother Son', it is virtually

impossible to go back to seeing them as romantic partners.

That incest thing just keeps screaming at you. The Travolta-Tomlin

resemblance was so obvious, one would think the director or

someone would have noticed during the filming. More

likely everyone had the sense to look the other way, sort of

like the 'Emperor's New Clothes'. For crying out loud,

will someone please give Travolta a crew cut or stick a blonde wig on

Tomlin? Either Travolta

was guilty of seducing his mother or he was having sex with his older sister.

The sex scenes were unbearable to watch.

The bad news was that

no one went to see this movie. The good news

was that no one went to see this movie. The

movie was pulled from theaters as fast as humanly possible,

but the ensuing criticism drove Travolta to madness. Although

his star

power survived due to the movie's

anonymity, his ego was

seriously damaged by the withering negativity. Many years later, Travolta

was asked to comment on the Moment by

Moment fiasco.

|

|

Interview Question:

"John, Saturday

Night Fever turned you into a cultural icon. What

was your reaction to the impact of Moment by Moment?”

Travolta:

"I

think with Fever, people were evaluating my impact

more than they were my acting. As for Moment by Moment,

my God, you would have thought I had committed murder or

something! It was serious trouble.

And

the weird thing was that everything in my life up to that

point, well, I don’t know of a career that had gone more

smoothly and successfully than mine. Welcome Back

Kotter, Carrie, Boy in the Plastic Bubble, Saturday Night Fever and

Grease - they were five major strokes that were 100

percent all right.

Unfortunately, at the very peak, when the lights were on

full and everybody was watching and waiting, here comes Moment by

Moment. Boom. Failure! And not just ordinary

failure, but gut-wrenching, horrible failure. I cringe every time I think about it."

|

Rick Archer's Note:

As

it turned out, Travolta ditched his upcoming role in American

Gigolo. The part went to Richard Gere instead.

Travolta did this because he decided he needed a tough guy

role to revitalize his soft, rather feminine screen image.

So Urban Cowboy became his next

stop. As it turned out, Travolta's presence during the filming

here in Houston and Pasadena created the same impact for

Country-Western dancing as Disco dancing. Saturday Night

Fever jump-started my dance career, but it was Urban

Cowboy that sent my dance career soaring into the upper

stratosphere. I owe a huge debt of thanks to John Travolta.

|

|