|

|

MYSTERY OF THE

TEXAS TWOSTEP

CHAPTER FOURTEEN:

FELKER'S DOWNFALL

Written by Rick

Archer

|

DARKEST DAY

AND BRIGHTEST DAY |

|

Rick

Archer's Note:

I am fond of an Arabic Proverb known as Two Days.

This proverb suggests that Life consists of alternating

cycles of Brightest Day-Darkest Day, Good Luck-Bad Luck.

When it is your Brightest Day, you can do no wrong.

When it is your Darkest Day, nothing seems to go right.

According

to this proverb, obstacles will be programmed into our life

and force us to deal with them.

My personal

belief is that 'Suffering' is part of life, but it

will not be limited to just one period. In my case, I

have identified six trips to Rock Bottom in my life.

The good news is that I always recovered. So the way I

see it, Life is divided into alternating cycles of ups and

downs.

Something I have

always found fascinating is how the Darkest Day principle

applies even to people who are truly gifted.

Some of the most famous people in history

seem to have had periods of their life where they really

struggled. One day I discovered a fascinating quote

made by J.K.

Rowling.

"Talent and intelligence will not inoculate anyone

against the Caprice of the Fates."

|

|

To me, Ms. Rowling's

observation suggests that everyone is scheduled by Fate to experience

hardship at some point in their life. That includes those with money, privilege, talent,

and intelligence. That includes a powerful man like

Clay

Felker, the guy who seemed on top of the world.

In this

chapter we will see how Clay Felker hit Rock Bottom.

The

Arabic Proverb warns people to be careful during

their Brightest Day. "When Life is for you,

do not be proud or reckless."

It is my theory that Clay Felker ignored this advice.

During his climb to the pinnacle of his profession,

Felker began to take success for granted.

Flaunting his position, Felker rubbed certain

important people the wrong way. As consequence

to his reckless behavior, in 1976 Felker made two serious mistakes,

thereby initiating his Darkest Day. He too

proved vulnerable to the 'Caprice of the Fates'.

|

|

|

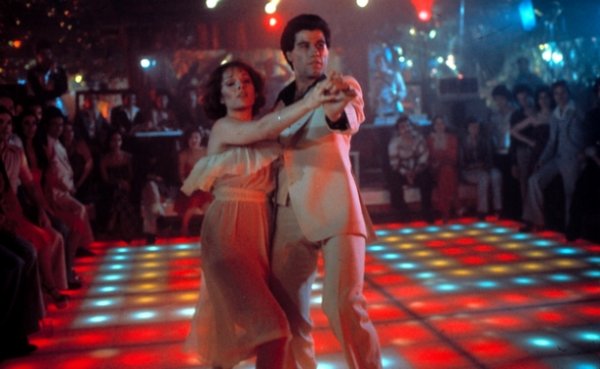

The moment

Robert Stigwood saw Nik Cohn's story in New York

magazine, he believed he had been handed the opportunity of

a lifetime. Well aware he had the right story, the

right actor, and the right music, Stigwood anticipated the

movie had the potential to make $100 million dollars.

Guess again. His movie made five times as much during

its initial release.

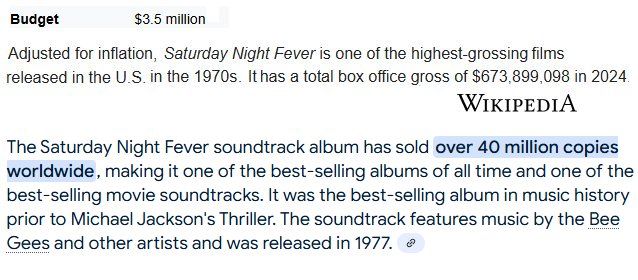

At the

time Saturday Night Fever made 500

MILLION Dollars

combined box office and soundtrack.

The soundtrack album kept selling and so did the

movie. Adjusted for

inflation, as of 2024 the movie generated a

box office close to $700,000,000. Considering the

movie's sound track is one of the largest selling albums in history

with 40 million copies sold, at a conservative price

of $10

we can assume it was worth at least another

$400,000,000. In other words, Saturday Night

Fever made A BILLION DOLLARS.

And how much did

it cost Robert Stigwood to make his Billion Dollar movie?

$3.5 million. Wow. Kudos to Stigwood. He

was smart to defy the skeptics and trust his intuition.

|

In 2007,

Sam Kashner penned a detailed 17-page, 10,000 word account of Saturday Night Fever. Kashner made it clear that

producer Robert Stigwood, actor John

Travolta, script writer Norman Wexler, and the three Bee Gee

brothers became wealthy and famous beyond their wildest

imaginations.

Another big winner was writer Nik Cohn. His name was listed prominently.

"So the deal [with

Stigwood] was made, and Nik Cohn was paid $90,000 for

the rights [to his story]."

Believe it or

not, Nik Cohn's lie became worth $500,000. Half a

million for a fake story. Amazing.

Sam

Kashner pointed out that Robert

Stigwood was not alone in recognizing the story's potential.

There were others.

"Back in the

70's it was almost unheard of to buy a magazine

article for a movie, but Cohn's 'Tribal Rites' attracted enough

attention that producer Ray Stark (Funny Girl) and a few

others bid on it."

In other words, all sorts of people noticed there was

something special about Nik Cohn's story.

However, one notable person

failed to notice anything interesting about the story.

Take a wild guess.

Considering

the thoroughness of Kashner's article, if Clay

Felker had been involved in the making of Saturday Night

Fever, we would assume his name would have appeared

as well.

Clay

Felker's name was nowhere to be seen.

For all the success tales that weaved through the improbable

Saturday Night Fever saga, try to picture Felker's

wounded pride when the movie proceeded

to become the cultural icon of the Seventies. Indeed,

the 'Ultimate trend spotter'

had

felt nothing but contempt for Cohn's story. So imagine

Felker's stupefaction when the story turned into a

national phenomenon.

Clay

Felker had wanted to cancel the story. He could not

put his finger on it, but there was something about Cohn's story that raised a red flag.

My guess is Felker smelled a rat. Like Robert

Stigwood, Felker should have trusted his intuition. However,

Felker's partner Milton Glaser persuaded him to

publish Cohn's story against his will.

The irony is

unbelievable. Without Felker's help, Cohn's scam

probably would

have never worked.

How

on earth could this brilliant man have missed this?

Wasn't Felker the man who could see the future? Not this

time. Despite his razor-sharp instincts for spotting unusual

lifestyles,

a story worth a billion

dollars passed right under his nose.

Casey at the Bat is a classic metaphor for the

dangers of complacency. With the game on the line, Mighty

Casey was so sure he would hit a home run that he didn't

even bother to swing at the first two pitches. Feeling

smug, Casey was shocked when he missed the third pitch.

Casey had struck out. The moral is to swing at every pitch because you might not get another chance.

However, if this happens to be your Darkest Day, sometimes

even the smartest guy in the room gets left holding his bat

on his shoulder. Clay Felker was the man who prided

himself in spotting trends before all others. And yet

the one time his talent could have really paid off, Felker

missed it.

Nik Cohn's scam was worth half a million.

Clay Felker never made a dime.

In simple terms, Clay Felker felt

exploited. He

had nothing to show for his contribution

but wounded pride.

|

|

Barry

Gibb of the Bee Gees once said to Nik Cohn, "This is all your bloody

fault, isn’t it?"

Nik Cohn

just nodded.

By hoodwinking Clay Felker into giving

his story credibility, con man Nik

the Slik scored the

richest payday of his life.

Sometimes truth is stranger than fiction. A

throwaway B-movie designed to give an idle actor something

to do

turned into a Billion Dollar Bonanza. This all

happened because some English stiff made up a fairy tale and

sold it as truth.

Cohn agreed to accept

the first offer made by Stigwood's representative, $10,000. However, once

Felker published his story, Cohn was paid $90,000

for rights to his story. Despite the lucrative jump from $10,000, Cohn wasn't

satisfied.

In addition to the $90,000, Cohn demanded to write the

screenplay. Stigwood caved in and paid Cohn

$150,000 to write the screenplay.

Nik Cohn was not

done. He proceeded to negotiate percentage points

for the

soundtrack album.

This was unheard of. It had never been

done before. Musicians got

percentage points, but never a writer.

However, Cohn had

seen how much money The Who had made from the

Tommy soundtrack. Well aware he had his mark over a

barrel, Cohn took Stigwood to the

cleaners.

Once Cohn's share of the proceeds from the best-selling

soundtrack album rolled in, estimates placed the haul around

$250,000.

$90,000,

$150,000, $250,000. Incredible. Indeed, Nik Cohn

cleared somewhere in the ballpark of half a million for a

fake story. How did he pull this off? First, the

publication of Cohn's story in Felker's magazine dramatically

increased the credibility of the story. But the real

break came when Stigwood guessed the story was worth

$100 million.

Ironically, Nik the Slick was not as talented as

he thought he was. His movie script was rubbish.

It was so bad that Stigwood

was forced to bring in another writer, Norman Wexler, to

finish the job. We can assume Cohn's script went in

the wastebasket. Be that as it

may, Cohn's fake story had made him rich.

It was the scam of

the century.

|

|

|

Simultaneous to

Nik Cohn's highway robbery,

Felker was in the fight of his life to maintain control of

his magazine.

Felker was up against a

ruthless billionaire named Rupert Murdoch. Making matters worse,

Felker's dilemma was a self-inflicted wound. It was

Felker's

own fault for letting the fox inside the henhouse.

Felker was a terrific

editor, but he had one major weakness... he liked to spend

other people's money. Felker's expenses were

so exorbitant, they out-stripped the magazine's resources.

His lavish spending on limousines, office space, costly

parties and personal

chefs drew heavy criticism from his magazine's board of directors.

One day Felker demanded they buy him a house in the

Hamptons so he could throw bigger parties. That was the last straw

for the magazine's Board of Directors. Clay Felker had

grown too big for his britches.

In 1976, New York was going broke. Fed up with

his

rampant spending, the Board told Felker to find a solution or start looking

for another job.

Felker did not

like being told to tighten his belt. No one talks to

him like that. Why not just buy the magazine himself?

Then he would have the last laugh. But first he had to

find a sugar daddy.

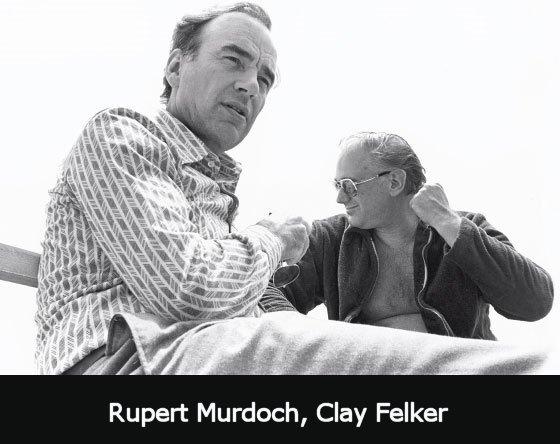

Clay Felker had recently been introduced to Australian media

mogul Rupert Murdoch by Katherine Graham, publisher of the

Washington Post. Graham had asked Felker to

show the city to the new kid in town. They lunched downtown and lounged seaside in

the Hamptons while discussing mutual business ventures.

In the process,

the two men became friends. Or so Felker thought.

|

Rupert Murdoch

was an Australian-born press baron who had just paid $30

million to add the New York Post to his chain

of newspapers in Australia, Britain and the United States.

Hoping to impress Murdoch, one day Felker invited his

so-called savior to visit one of his lavish parties.

No doubt Murdoch's eyes bulged as Felker guided a parade of

celebrities, businessmen and politicians over to meet him.

No doubt this was the moment Murdoch realized that Felker's

magazine could be of value to him.

Taking note of

Murdoch's deep pockets, in November 1976, Felker made a bold move.

He casually mentioned his boardroom

problems to his potential benefactor, then asked if Murdoch might be

interested in making an investment in the magazine.

Murdoch's eyes lit up immediately. Felker's suggestion was akin to asking the friendly

neighborhood fat boy to

watch his hot dog for a while. Thanks to Felker's big

mouth, Murdoch had just realized the smart, sophisticated New York magazine was not only in play,

it was exactly what he was looking for.

Licking

his

chops, Murdoch smiled

politely, then offered an invitation.

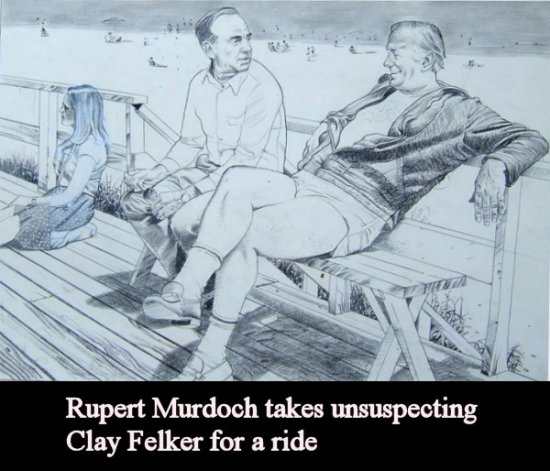

"Why,

sure, Clay, why don't you drop by my beach house this weekend?

Let's

have a talk!"

Felker must have been in some sort of fog. Or perhaps

he had fallen under the spell of 'Cosmic Blindness'.

You knew I was going to bring that up, didn't you? Ordinarily a shrewd man with killer instincts, Felker

had missed what Nik Cohn was up to. Now he missed what

Rupert Murdoch was up to as well. Felker did not seem

to understand that Murdoch was looking to

expand his media empire. That was why Murdoch had come to

New York in the first place. Murdoch had started with

the purchase of the New York Post,

a blue-collar tabloid. For his next conquest, he could

use this magazine as a way to court favor with the city's wealthy movers and shakers.

Meanwhile Felker remained blind to the danger. He was

so certain that Rupert Murdoch was a well-meaning buddy,

Felker poured his heart out to Murdoch during a fateful

weekend in the Hamptons. Journalist Susan Braudy

offered this startling eye-witness account:

|

"I had dinner with

Rupert and Clay

at

Murdoch’s rented house in Southampton. I was there

as a weekend houseguest of Clay Felker, the

publisher of New York magazine. Murdoch’s

daughter and son served steak and fresh baby peas. Flawlessly

tasteful. Intimate. A stealthy trap. For Murdoch, the

dinner party was a high-level espionage mission.

Clay had no

inkling that Murdoch was secretly positioning himself to

steal New York magazine out from under him. Clay was loquacious

throughout the meal. He explained Manhattan things to

Murdoch who Clay clearly saw as a bit of an Aussie rube. Clay

waxed eloquent about his writers Aaron Latham and Gail Sheehy who were

present at the meal. Clay explained my presence in

terms of Ms Magazine which he had helped

launch. This is where I wrote and edited.

Clay bragged about

his fabulous parties. He confided to

Murdoch that he got his best stories by listening to

dinner party conversation. He was oblivious to his

mistake. This time it was Murdoch who was doing the listening,

turning the tables so to speak. Clay got no stories

at this dinner because Murdoch said almost nothing. He

asked one or two flattering questions and that was it.

Murdoch was doing to Clay what Clay usually did to

everyone else... listen and think of ways to take

advantage.

A month or so

later, Murdoch seized New York magazine

and instantly fired Clay despite assurances to the

contrary."

|

|

Clay Felker had been out of his mind to speak so candidly to

the fox.

Andrew Tobias, one of Felker's writers, had this say:

"Clay was not great with money.

He was always

asking me for financial advice like how he could stint on

his editorial package. Clay's bread and butter was

creativity. The stories, graphics and

writing meant far more to him than profits. Then

came the day he met a terrific young Australian

publishing tycoon. Clay told me, “Andrew, you’ve got to go meet this guy!”

Clay assumed he was setting up Murdoch to be

his shining knight. When Clay sent me over to visit Rupert Murdoch,

Murdoch ended up interviewing me about the magazine.

That's when I got that funny feeling. Sure enough,

to Clay’s

consternation, Murdoch grabbed the magazine right out from under him."

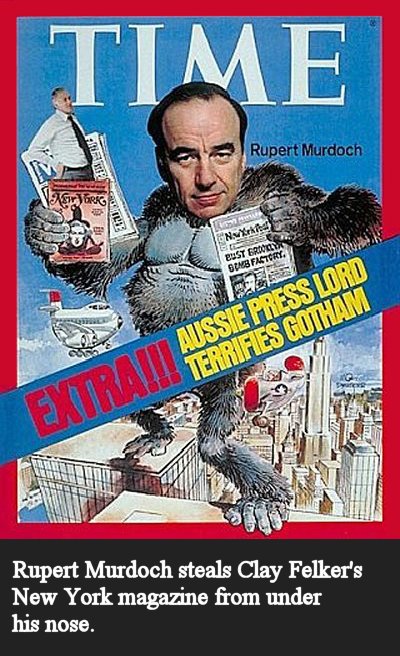

Once Murdoch realized Felker had alienated the board of

directors, he saw his opening. At the same time

Murdoch was sharing meals with Felker, he was negotiating

behind Felker's back with Carter Burden, the magazine's majority

shareholder.

According to the New York Times, Murdoch made a secret

offer to the board of directors to buy New York

magazine.

Clay Felker never saw it coming until it was too late.

Worried

he might lose his magazine, Felker asked Katharine Graham to

back him in a bid to keep the company.

When Graham learned of Murdoch's backdoor dealings, she

called Rupert Murdoch to beg him to reconsider.

“Don’t do this to the boy, Rupert. Don’t destroy this boy, don’t take this boy’s magazine from

him.”

Murdoch could have cared less, so Katherine Graham tried

another tactic. She

offered to buy out Carter Burden, the

principal stockholder, who held 24% of the stock.

That is when Felker's Karma came back to bite him in

the ass.

Carter Burden had once been the

subject of a highly unflattering profile in Felker's magazine.

Holding a grudge, Burden turned down Katherine Graham. On the

following day Murdoch flew to Sun Valley, Idaho, where

Burden was skiing. There on the sunny snow-covered

slopes, the two men made a deal.

Murdoch had sensed weakness. He was a shark and there

was blood in the water. Felker might be a great

editor, but he was a lousy businessman. Given how fed up

the Board was with Felker's spendthrift ways, all

Murdoch had to do was wave money and they took it. The moment Murdoch bought the

New York

magazine, he told Felker to hit the road.

Despite Felker's deep connection to his baby, Felker was of

no use to Murdoch.

A ship cannot have two captains.

Felker felt betrayed, stabbed in the back.

He had expected Murdoch would help him acquire

New York magazine,

not take it for himself. He had trusted the wrong person.

Felker was down to one last hope.

His stable of talented writers

was deeply loyal. They threatened to revolt

if Murdoch fired Felker. However, the writers got nowhere.

Murdoch called their bluff. If they left, Murdoch said

he would replace them

faster than the furniture, adding that there's always another

English major hungry to make their mark. Besides, try finding another job in

this market, especially after Murdoch put the hex on them. The revolt collapsed

faster than a punctured balloon.

Here is how Richard Reeves, one of Felker's stunned writers, put it:

"Part

of what happened was Carter Burden, who was majority

stockholder. Burden hated Clay because Clay hated

him. Clay had no use for people like Burden or the other

money people. He - mistakenly, I think - treated them

like dirt. Clay paid a heavy price for that

attitude.

[After Murdoch took over] this was a time that

we all thought the power was with the writers,

with the creative people. We were wrong. In a way we

were forced to learn what

they already knew in Hollywood: That’s not the way it is.

The power is with the money. While we wrote about

that all the time, and while Clay understood this fact

of life

intellectually, as a businessman I don’t think he got it.

That is what led to his downfall."

Gay

Talese, writer at Esquire:

"Power and the access to

power is a kind of addiction that sooner or later takes

over the brain waves of an editor.

Clay papered that house of his with personalities

and recognizable people, people who were going to fit

into his plan as writers, art directors, girlfriends, a

movie star. When I first

saw him was at a party with Sammy Davis Jr and Jacob

Javits and there were pretty girls abundant.

Being around so many important people, I think it went

to his head."

|

1976 and 1977 were tough years for Felker.

The toughest blow of all was losing his beloved

magazine. Once

Murdoch showed him the door, Felker was

heart-broken. He was also out of a job.

Humiliated, Felker

lost his pride,

his job,

and his magazine, the most precious thing in the

world to him. Felker had been synonymous with

New York magazine. But

not any more. Clay Felker was being called a loser, a

chump.

Felker had been outsmarted by Nik Cohn and outfoxed by Rupert

Murdoch.

No one but

Felker knew the inside story of how Nik Cohn had embarrassed him,

but the

Murdoch situation was different.

Felker's giant

reputation was badly tarnished when the news emerged about how

Murdoch had tricked him. Imagine what it must feel

like to become the laughingstock in the media capital of the

world.

People laughed at his downfall.

No doubt Felker was keenly aware that

his self-destructive behavior had gotten him into this fix.

What is Rule Number One when dealing with people who have

control of your Destiny? "Don't bite the hand that

feeds you." Felker was forced to acknowledge how

his unflattering profile of Carter Burden had led to his

destruction.

Brightest Day, Darkest Day. This was Felker's Darkest

Day.

Saturday Night Fever

was being filmed in Brooklyn at the same time that Clay

Felker was wrestling with Rupert Murdoch. Shortly

after Felker was fired in late 1977, the movie debuted in

December. At the exact moment

Clay Felker was thrown out on the street, he was forced to watch helplessly as

the box office and soundtrack made

Saturday Night Fever one of the most lucrative films in

cinematic history.

This had to be the lowest moment of his

life.

Everyone who touched this movie got

rich. Nik Cohn came away with half a million. Robert Stigwood made

more money than Midas. John Travolta and the Bee Gees rocketed to

stardom. Felker was aghast to realize he was the big loser

in this amazing bonanza. In particular, he seethed at

the indignity of letting Nik Cohn leapfrog to the

stratosphere using his unwitting shoulders for lift-off.

Feeling like a chump, it is fair

to assume Felker sought redemption.

Bitter

at his fate, Clay Felker decided he had a score to

settle.

So what was he going to do about it?

|

|

|

|