The Roman Game

of Thrones

Written by Rick Archer

October 2016

|

| |

|

Rick Archer's Note:

The inspiration for this story

came from the well-regarded British miniseries known

as I, Claudius. The miniseries

was based on a book of the same name written by

Robert Graves.

Roman history, with its

conquests, technical advancements, and impact on our

modern world can be one of the most fascinating

subjects known to man. Roman politics, however, is

very difficult to understand.

What Robert Graves did with

I, Claudius is present all the complex

political intrigues of the early empire and make

them both comprehensible and fascinating at the same

time. Robert Graves told his story from the

perspective of Claudius, the fourth Emperor of Rome.

Claudius was intellectually

gifted but physically deformed. His family had

no idea the boy was actually smart. They took

one look at his deformities and concluded he was

mentally deficient. Ashamed of his stammering,

limp and nervous tics, they kept him out of public

life. In addition, they all concluded that

Claudius was no threat to his ambitious relatives.

Due to extensive inbreeding

within the family, one has to wonder if Claudius was

one of the victims. Even as his symptoms begin

to wane in his teenage years, people had trouble

taking him seriously. Only a couple people

were on to him. As a teenager, Claudius wrote

a history of the civil wars. Unfortunately, it

was far too truthful and critical of the emperor

Augustus. His mother and grandmother quickly put a

stop to it. They told him to keep his thoughts

to himself for his own good.

This was a lucky break for

Claudius. Claudius caught on that his very

survival in this murderous dynasty depended upon

maintaining his family's incorrect assumption that

he was a harmless idiot.

Claudius concluded that his

best chance to survive the Curse of the Imperial

Palace was to convince everyone that he was a total

fool.

While everyone around him

either died young, was exiled or went insane,

Claudius somehow managed to hide in plain sight from

the danger. He would live to become an

effective Emperor.

|

|

|

THE

ROMAN GAME OF THRONES

Hail to

the Seven Caesars!

|

|

1 Julius Caesar -

2 Augustus -

3 Tiberius -

4 Sejanus -

5 Caligula -

6 Claudius -

7 Nero - |

The

Man Who Ended the Roman Republic

The Man Who Was

First King

The Man Who Did

Not Want to be King

The Man Who

Would Be King

The Man Who Should not Have

been

King

The Man Too Stupid to be King

The Monster Who Ended the Julio-Claudian Line |

| |

|

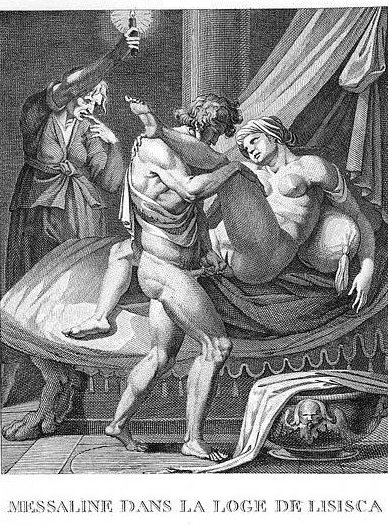

This story is dedicated to the Seven Caesars and to the women who

manipulated them at every turn. We have all heard of ambition gone

wild, corruption, and dirty

politics. We have heard of sexual perversion, cruelty,

and debauchery. Now add political assassination, poison and

complete madness to the mix.

There is no way to

explain how stunning some of these stories are. They must be

read to be believed. If there is one word that could describe this

era, it would be "excess." The Romans did everything to

excess. Too much killing. Too much sex. Too much

insanity.

And too much cruelty.

Endless cruelty.

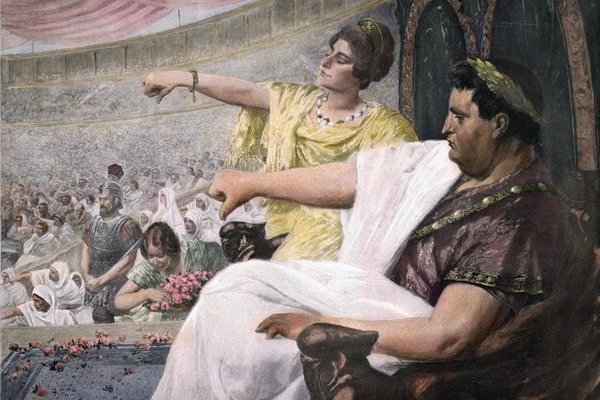

Look no further than

the savage blood sport recreation known as the Games. Here we

have Romans watching slaves

bash their comrade's brains during gladiatorial contests,

cheering as defenseless Christians are slaughtered by fierce animals,

enjoying criminals tortured in public for amusement, seeing helpless

animals abused in hideous ways, all the while laughing and jeering at

the suffering - and you begin to comprehend this was a

horrible, violent society.

Why they call it the

'Roman Civilization' is a mystery. These people were NOT

civilized.

|

|

| |

|

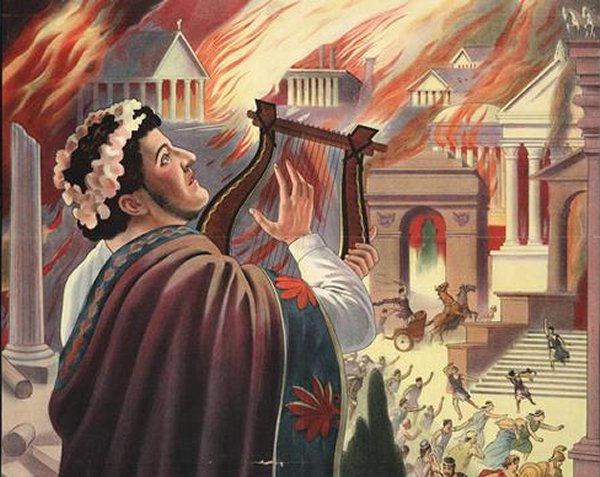

Chapter One: Julius Caesar

|

Our story begins with Julius Caesar.

To understand Roman politics, one must take into account the

fervor Roman citizens clung to their freedom. Rome had

once been a monarchy. Sick of tyrannical rule, in 509

BC the Romans overthrew their king. The increasing

power of Julius Caesar was deemed the greatest threat ever

to this cherished tradition.

At the time when Caesar arrived on the

scene, the Republic was in dire straits. Roman political

order was in chaos. There was street violence and rioting.

To some the Roman citizenry was falling victim to moral

decay. Many believed that it was only a matter of time

before the Republic would fall. Currently the Senate

was the seat of all power, but the Senate was broken into so

many warring factions that nothing could get done.

Does this sound familiar?

Julius Caesar's early career involved

his rise to power by

means of the First Triumvirate. In 60 BC Caesar made

friends with two men. One was Crassus, the richest man in Rome.

His

large loans would finance Caesar's burgeoning political career.

The other was

Pompey, a political leader of the Roman Republic who came

from a wealthy Italian provincial background. Pompey was a

terrific general who advanced his career by successful

leadership in several campaigns.

At the time when Caesar was no better than a mere governor,

Pompey and Crassus were bitter rivals. Crassus and Pompey were far more powerful than Caesar.

Caesar decided that to curry favor with one man meant making an enemy

of the other. Although Caesar

had the least power of the three, he managed to talk the two

opponents into meeting with him. Caesar suggested they form a

Triumvirate. Their triangle became known as 'the three-headed monster' by

their

enemies. It was an apt description.

Into this vacuum came the The

Three-Headed Monster. The three men seized the

opportunity for personal gain. Despite their

individual differences and pure animosity, the three men

would remain in control through bribes and threats to

dominate both the consulship and military commands. In

particular, Caesar gained the most. Not only did he

obtain a consulship, he gained the most coveted military

assignment of all: Conquest of Gaul (France).

It was in Gaul where Caesar achieved

his fame. Caesar's victories in the Gallic Wars

extended Rome's territory to the English Channel and the

Rhine. Caesar became the first Roman general to cross

both when he built a bridge across the Rhine and conducted

the first invasion of Britain. Caesar was not only a

great military commander, he had keen political instincts.

He wrote vivid stories of each conquest and sent these

reports back to Rome. Caesar's Gallia became a

must-read for every citizen of Rome. His fame grew

wide.

The First Triumvirate ended in 53

BC. It had been an unstable political alliance from the

start. It only lasted for seven years. None of three men

ever trusted each other.

First came the news that Crassus was dead. Crassus had died

fighting the Parthians in ancient Iran at the Battle

of Carrhae, 53 BC. That left Caesar and Pompey as the

two undisputed powers of Rome. Neither man was interested in

sharing power. However, at the moment, Pompey held the upper

hand since he was based in Rome and Caesar was still in Gaul. Caesar knew his likely rival had the inside

track to gain political prominence. It was obvious that

Caesar and Pompey would have to fight it out for the control

of Rome.

Caesar completed the Gallic Wars in 51

BC. In 50 BC, the Roman Senate, led by

Pompey, ordered Caesar to return to Rome. Caesar was

well aware that Pompey had allied himself with many enemies in Rome

prepared to take him down. Considering Caesar had no political rank

in Rome, at the least he expected to be politically marginalized if

he entered Rome... or perhaps they would just murder him.

Caesar had two

powerful assets: his fame and his army. He knew the people

of Rome would welcome him. But he had no guarantee for his

safety since Pompey had ordered Caesar to disband his army.

Caesar had no intention of walking into the obvious trap

unprotected. Therefore Caesar refused to relinquish his

army. Frustrated at Caesar's defiance, Pompey accused

Caesar of insubordination and treason. If Caesar were to

enter Rome with his army, Pompey said it would be an act of

war. That threat did not stop Caesar.

On 10 January 49 BC Caesar crossed the Rubicon River, an

event known as 'Crossing the Rubicon'. With him was a

single legion. The Rubicon was the northern frontier boundary of

Italy. No army was allowed inside this protective

barrier. Thus Caesar knew full well his bold action would

ignite civil war. Aware of the danger ahead, Caesar uttered

his immortal words "The die is cast."

|

Thanks to his success in Gaul, Caesar returned home with an

intimidating military reputation. Despite greatly

outnumbering Caesar and his single legion,

Pompey was terrified of Rome's greatest general. Pompey

turned heel and ran.

Leaving his top general Mark Antony

behind to

watch Rome for him, Caesar chased Pompey to the southern tip

of Italy. Then he chased Pompey to Greece where he

finally caught up to him. Caesar

soundly vanquished Pompey's army on the fields of Pharsalus

in an extremely short battle. Afterwards Caesar was disgusted to find

Pompey had again fled the scene. Pompey escaped to

Egypt and sought refuge in the court of Ptolemy. Bad move.

Before Caesar could reach Egypt, Pompey was behead by a Roman loyal to Caesar

who was stationed there.

Caesar's trip to Alexandria

was not a total waste. He found great pleasure in the

arms of the Egyptian temptress Cleopatra.

Following

his Egyptian dalliance with Cleopatra, in

47 BC Julius Caesar returned to Rome and

began to dominate the political

landscape. In 44 BC he was given the powers of

Dictator. Now it was only a matter of

time till he made himself Emperor. Seeing the last

chance of to save the democratic Republic from slipping

away, Julius Caesar was murdered

on the steps of the Senate

in March, 44 BC.

60 men participated in the execution.

Beware

the Ides of March.

|

|

|

Chapter Two: Octavian and Mark Antony

|

Following

the assassination of Julius Caesar,

there was an

enormous political vacuum. The conspirators apparently had no

long-range plan. So, in a major blunder, they did not

immediately kill Mark Antony when surprise was still in their favor.

Antony wasn't stupid. He correctly anticipated that the dictator's assassination would be the start of a

bloodbath between Caesar's supporters and enemies.

In the turmoil surrounding

the event, Mark Antony escaped Rome dressed as a slave.

Now that Mark Antony had survived the coup, he was in the perfect position to inherit Caesar's power. The

conspirators had only a band of gladiators to back them up.

Meanwhile

Antony had a legion, the keys to Caesar's money boxes, and

access to Caesar's will. Furthermore, as Caesar's right hand man, Antony was already a recognized

and respected leader

of Rome. Mark Antony clearly had the inside track to the throne.

Mark Antony had gotten his start as a military leader under Caesar

during the conquest of Gaul. When Caesar decided to patrol the

Mediterranean in chase of Pompey, he put Mark Antony in charge of

running the affairs of Rome. Mark Antony was a formidable man

in his own right. Although Caesar and Antony had

their differences, Caesar knew he could trust Antony.

Unfortunately, on the day of the murder, the conspirators had the

sense to delay

Antony elsewhere in the Roman Forum. Antony learned of the murder plot just moments before it took place.

He rushed to warn Caesar, but, alas, Antony was

too late.

Afterwards, it was Mark Antony who decided to punish Caesar's

assassins. First he negotiated a truce with the assassins by

promising them amnesty. But

then he turned the tables on them by publicly exposing their role in Caesar's

death in a marvelous speech at the funeral.

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears; I come to bury

Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after

them, the good is oft interred with their bones.

So let it be with Caesar. -- William Shakespeare

The citizens of

Rome were outraged to learn the truth. Their misdeeds brought

to light at the funeral, the assassins ran

for their lives.

When it was time to read Caesar's secret will,

Mark Antony received a nasty shock. Caesar's will named an

unknown boy by the name of Octavian as his heir. In addition, Caesar's will

posthumously adopted this same Octavian

as his son. Caesar's name and considerable estate would go to

Octavian.

Octavian? Who was Octavian? Scarcely anyone in Rome had

ever heard of him. Antony barely even knew who Octavian

was himself.

This moment marked the start of 17 year journey for Octavian

on his way to become the supreme leader of Rome.

Considering Octavian

was a long shot at best,

this was the start of a very remarkable story.

Octavian

was the son of Atia. Atia was the

daughter of Julius Caesar's only sister Julia.

Julius Caesar was so clever that he had kept Octavian in

hiding for years without explaining to anyone what he was up

to, not even to Atia, the boy's mother.

Caesar had

done this

to shield the lad from assassins.

To further ensure

the boy's safety, Caesar had deliberately hidden his

great-nephew from the world by sending him to Greece to

continue his education.

Now Octavian was in for the shock of a

lifetime.

Gaius Octavian was a

short, thin, sickly 19-year-old schoolboy

living in Greece when he learned the

news. After hearing that his

great-uncle had been tragically

murdered, he was stunned to learn

that Caesar had named him as his

heir. Octavian barely knew the man.

Caesar was always somewhere - Gaul, Greece, Egypt, Hispania,

Asia Minor - fighting some battle. With the weight of

an Empire dropped upon him, imagine how

overwhelmed Octavian must have felt.

Octavian knew that his uncle had

always taken an interest in him.

Octavian

knew he had impressed Caesar on several occasions,

but his illustrious uncle had never revealed his true

thoughts. Now he trembled. He was a mere schoolboy with no

political experience, no army, no money, and no military training.

Although he had just been

named the successor of the greatest

politician in Roman history, there

was no guarantee that the rule of law would be followed.

Rome was like the Wild Wild West... any gunslinger could

take him down.

Octavian had one asset... he was very smart.

Octavian suddenly grasped why his uncle seemed to go out of

his way to avoid him. Octavian guessed that

Caesar had expected to groom the boy into this role in due

time. However,

since Caesar was unaware of his impending doom,

he had been cut down shortly

before the boy's initiation was about to begin.

The assassination

marked a dangerous time for this young man.

How dare he try to step into the famous dictator's shoes!

Octavian had no army.

He had no security guard.

He had no allies or patrons.

He had no reputation.

He had

no money. Furthermore, Mark Antony was

sure to object. How would Octavian ever claim the prize?

Octavian had

only one thing

going for him -

Caesar had named him the successor. Octavian

knew he would be a marked man,

but surely the name of Caesar

meant something. Octavian was game

to try. Against the worried advice of his family,

Octavian boldly set off for Italy

to claim his inheritance.

Octavian had a plan. He knew

a direct trip to Rome would be too dangerous.

Mark Antony would likely

have him murdered on the spot. So what if Caesar's will had

named young Octavian the legal heir? What meaning would the

document hold if Octavian was dead? Then Antony would have

no one to stand in his way from assuming

Caesar's role.

Octavian knew time was of the essence.

In April, just one month after Caesar's death, Octavian took a detour to Brundisium at the southern tip

of Italy. Octavian knew a sizable army of

soldiers loyal to Caesar was stationed

there. Octavian introduced himself to

the commander of Caesar's legions. He showed the

man the documents naming

him Caesar's heir. Caesar had always been good to his armies.

Octavian was gratified to discover there was

still great loyalty to

his uncle's name.

The

commander was impressed by

this

precocious boy's confidence and courage at such a

young age. Maybe

Caesar knew what he was doing when

he picked young Octavian to take his place.

Why not give the kid a

chance?

After the warm welcome by Caesar's soldiers at Brundisium,

Octavian demanded (and received) a portion of the funds that

were allotted by Caesar for the intended war against Parthia

(Iran)

in the Middle East. This amounted to 700 million sesterces.

Since that money was

public funds, this must have taken

some smooth-talking. Octavian

made another bold move. Acting

without permission, Octavian appropriated the annual

tribute that had been sent from Rome's Near Eastern provinces

to Italy. Mind you, this was a 19

year old boy making these

moves. Octavian may have

been new at this, but he obviously had

his uncle's genes going for him.

After his initial

visit to Brundisium, Octavian began to visit other pockets

of soldiers as well. Throughout

April, Octavian continued gathering support. By

emphasizing his status as heir to Caesar,

Octavian bolstered his personal

recognition with veteran legionaries and with troops

designated for the Parthian war.

Next Octavian won over Caesar's former veterans

stationed in Campania.

In just one month, Octavian had gathered an army of 3,000 loyal veterans.

Now that he had an army

behind him, it was time to head to Rome. Arriving in Rome on

6 May 44 BC, Octavian found the consul Mark Antony, Caesar's

former colleague, locked in an uneasy truce with the

dictator's assassins.

One can imagine this was a very

interesting meeting.

Octavian, 19, was not all imposing.

He was a thin,

weakling kid who looked more like a nerd than a leader.

Across the table was Mark Antony, 44, a brute of a

man. Antony was a war hero who knew how to

wield a sword, command armies, and fend off political enemies

with apparent ease. Nevertheless,

the kid was unfazed by Antony's reputation. Octavian demanded his money

from Caesar's estate and asked what Antony had done to chase

down Caesar's assassins.

One can only

wish

to have seen the look on

bitter Antony's face.

From his grave, Caesar surely

smiled at Antony's discomfort. Previously Antony

had thought Caesar was a fool for

picking this sickly kid. Now

Antony formed a new impression.

Antony knew Caesar had spent his whole life evaluating

talent. Antony was forced to admit

that there was a quality in the lad

that hinted at greatness.

No doubt Antony wanted to simply

strike the lad down and be done with him, but there was the

small problem of that army loyal to the kid

sitting outside his door.

So the boy was not harmed.

Nevertheless, Antony took a harsh attitude towards

Octavian due to his age.

Why not try to intimidate the boy? Antony

refused to unblock

the boy's inheritance from Caesar.

Indeed, Octavian failed to

wrest any money from Antony that day, but

he was encouraged nevertheless. At

least Octavian got the man to accept his political

legitimacy.

There was a new kid in town.

Over the next

few months, more veterans of Caesar's legions

lined up behind their dead leader's chosen heir.

The kid had charisma. Armed

with Antony's acceptance and this

increased military backing, Octavian had

established a foothold in Rome. It

was time for the the next step. Noting

that his uncle had named Octavian his son and rightful heir,

the young man renamed himself 'Gaius

Julius Caesar'.

Using his impressive new name to full advantage,

he quickly won the allegiance of

his great-uncle's political supporters

and assumed a role in government.

Now Octavian took a page out of Caesar's playbook. If you

can't beat them, join them. Rather than oppose Antony, he

persuaded his greatest rival, a man twice

his age, to join a Second Triumvirate with Lepidus as

the third man. They joined

forces to avenge the death of their mutual benefactor.

Together, the three of them would chase down the assassins

and any troops loyal to them.

Octavian worked with Mark Antony and Lepidus to

track down all of Caesar's murderers. They defeated Cassius

and Brutus in the Battle of Philippi over in Greece in 42

BC. It had taken two years, but the

death of Julius Caesar was avenged.

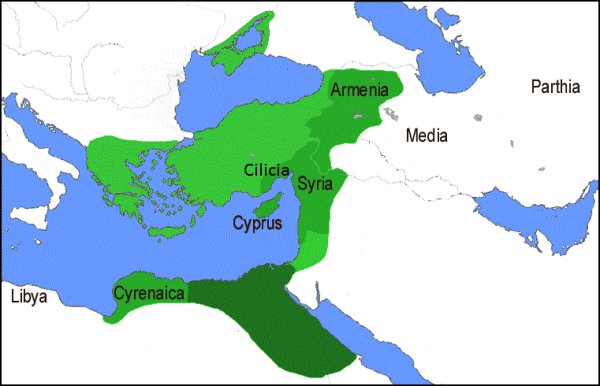

Now the three men

turned their wary eyes on each other. They carved up

the Roman territories. Lepidus got Africa, Octavian

got Italy and the west, while

Antony took the east. There

was no further bloodshed for a while, but

Octavian was certain Antony

was up to no good.

| |

To be sure, Antony was indeed

up to no good, but it had nothing to do with plots

or more fighting. It was time to make love, not war.

Cleopatra had been in Rome with Julius Caesar at the

time of his death. During this time, Mark

Antony had developed a serious crush on the woman

and Cleopatra knew it.

Following the

elimination of the Caesar's assassins, Antony received an

invitation to visit Cleopatra. So he took a

trip down to Egypt. The twosome began a passionate

affair in 41 BC.

Only one problem... Antony was

still married to Fulvia, the most powerful woman in

Rome. Supremely jealous and quite irritated at

her straying husband, Fulvia

fomented a war with Octavian in Italy as a way to

draw her husband home.

This led to a

remarkable stand-off. On the eve of battle,

the generals of Octavian and the generals of Antony

refused to fight each other because they had all

once served together under Julius Caesar. This

unusual move

forced the astonished Antony and Octavian to patch up their

differences.

|

|

| |

About this time, Fulvia conveniently

died, more than likely from a timely dose of poison.

To solidify

their tenuous relationship, in 40

BC Octavian demanded Antony

marry Octavia, Octavian's sister,

as a show of allegiance.

With a heavy heart, Antony gave in.

| |

Take one guess what Cleopatra's

reaction was.

Two years passed. Antony

could not get Cleopatra out of his mind. He

left Octavia and went crawling back to Cleopatra.

Cleopatra was the scorned

woman. In return for her forgiveness,

Cleopatra demanded a show of loyalty.

Antony asked what she had in

mind.

Cleopatra demanded Antony cede

control of a dozen Roman territories in the East to

her and marry her.

Antony accepted her

demands. He divorced Octavia, sister of

Octavian, so he could marry

Cleopatra. Then he

secretly ceded several Roman territories under his control to

Egypt.

Antony

had made his move.

He was preparing to

dominate the Roman Empire from the East.

With the combined

armies of Antony and Cleopatra, he had the military

might to do so.

|

|

| |

Octavian was well

aware of the growing threat posed by the power duo.

Unfortunately for Octavian, the people of Rome were tired of

fighting this Civil War.

So an uneasy truce developed. For

the next ten years, Octavian could do

nothing more than wage a public

relations battle. He made

sure that Antony's flirtations with the foreign queen did

not sit very well in Rome.

Over

time, the Roman people began to distrust Antony.

The final straw

came when someone tipped off Octavian

that Antony had betrayed Rome. Octavian

stormed the sanctuary of the Vestal Virgins and forced their

chief priestess to hand over Antony's secret will.

To Octavian's delight, the will

stated

that Antony intended to give away Roman-conquered

territories as kingdoms for his sons by

Cleopatra to rule. In addition

Antony had plans to build a tomb in Alexandria

for him and his queen to reside upon their deaths.

Octavian smiled. If Antony and Cleopatra were lucky,

those tombs would be ready just in time.

Seeing his chance

to get rid of his rival, Octavian declared Antony a traitor.

Learning of Antony's treachery, now

the Roman people were mad enough to

help Octavian wage war on Antony and Cleopatra

and regain control of Rome's eastern territories.

In 31 BC, 13 years after the

death of Caesar, Octavian trapped Antony and

Cleopatra's forces on the Actium promontory in western

Greece.

Forming a blockade, Octavian forced a sea fight

in the waters on the western shore of

Greece. Octavian

turned to his best friend Marcus

Agrippa. Realizing Agrippa

was the better military leader, Octavian

let him assume control of the Roman

fleet. This led to the Battle of Actium, one of

the most famous sea battles in history. After

Antony was routed, he and

Cleopatra fled back to Egypt with Octavian on their heels.

Octavian and Agrippa

went on to conquer Egypt.

Pinned against the wall with no refuge to escape to, Antony committed suicide.

He stabbed

himself with his sword in the mistaken belief that Cleopatra

had already done so. When he found out that Cleopatra was

still alive, his friends brought Antony to Cleopatra

and he died in her arms.

Cleopatra knew full well that if she was caught, Octavian

would parade her through the streets of Rome.

Cleopatra would rather die than suffer this humiliation. Cleopatra took her own life with the bite

of an asp.

Upon the demise of Antony,

Octavian had emerged as the sole master of the Roman

world. Now that the Senate was no

longer the main seat of Roman power, the Republic was finally ready to succumb to

Octavian's imperial authority.

|

|

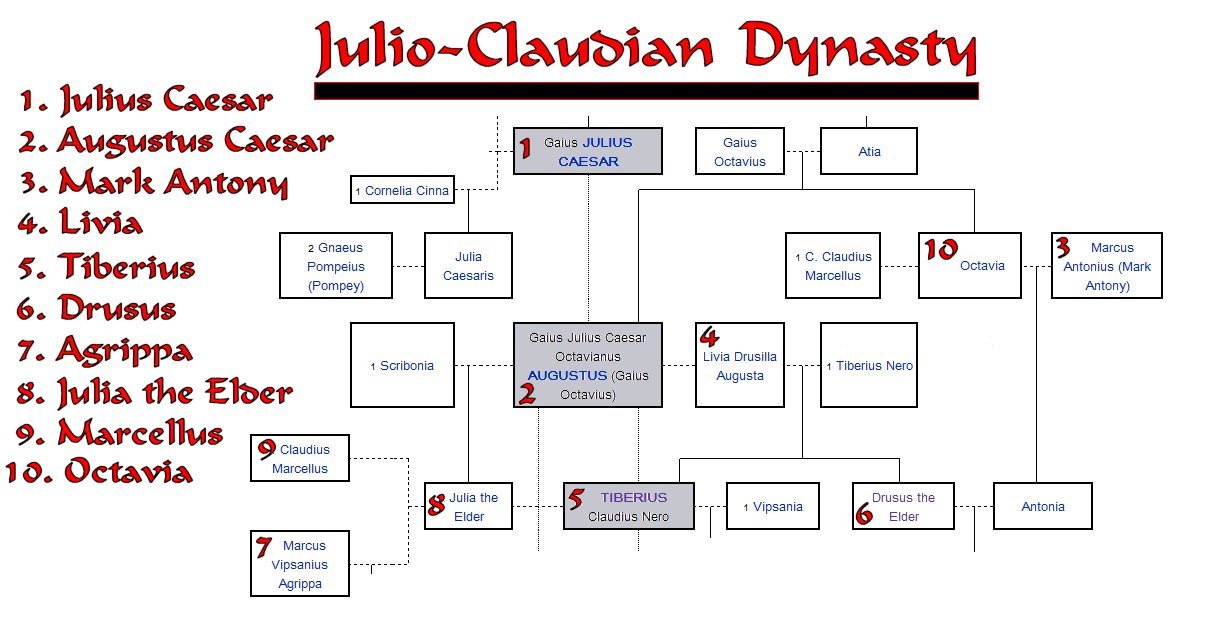

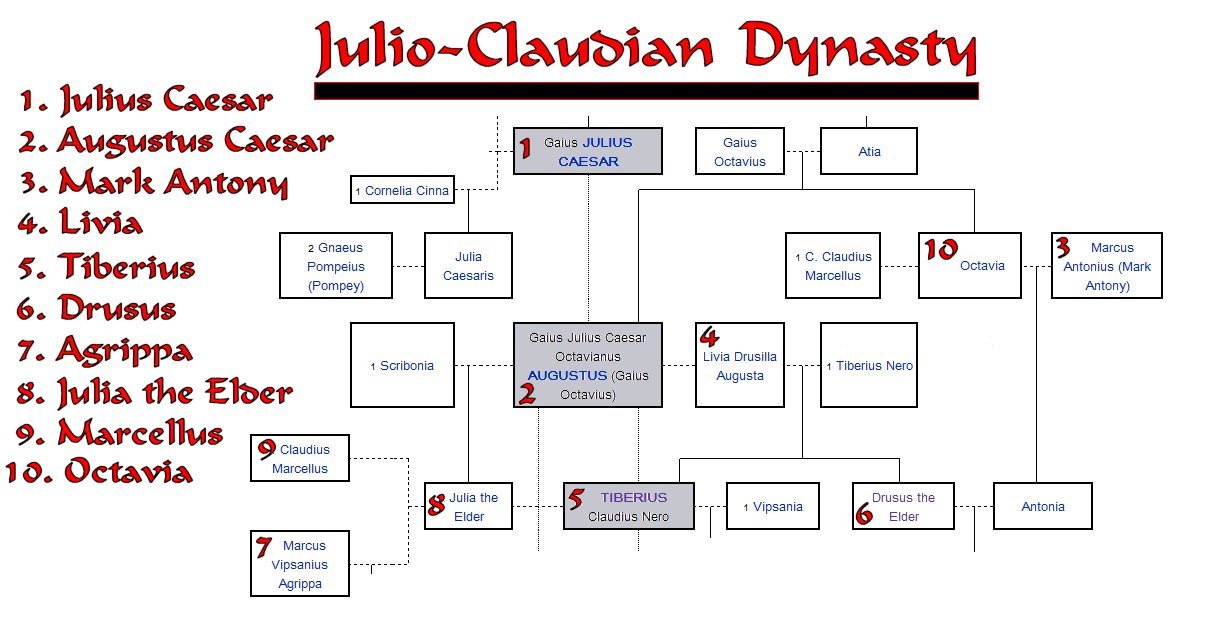

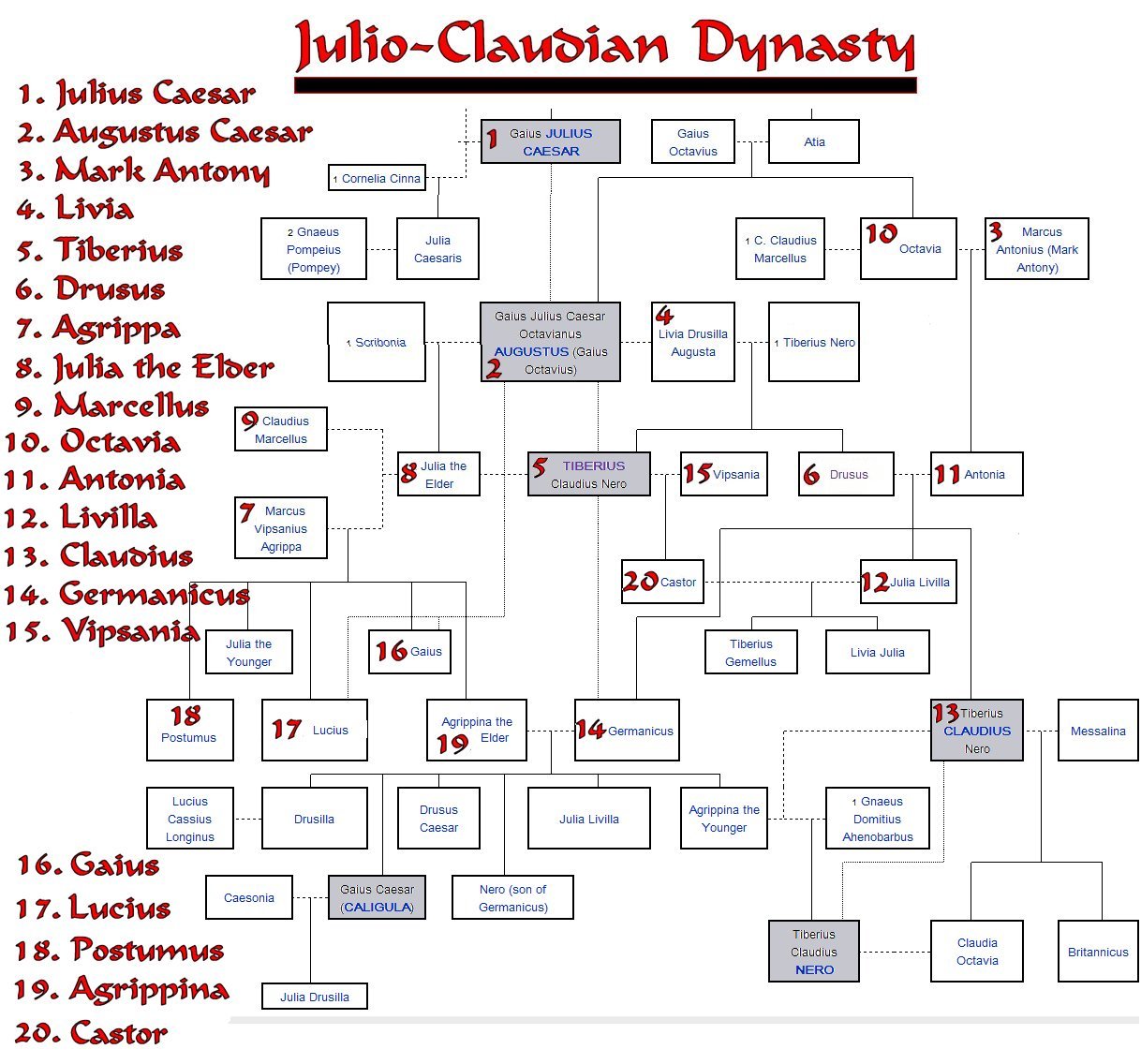

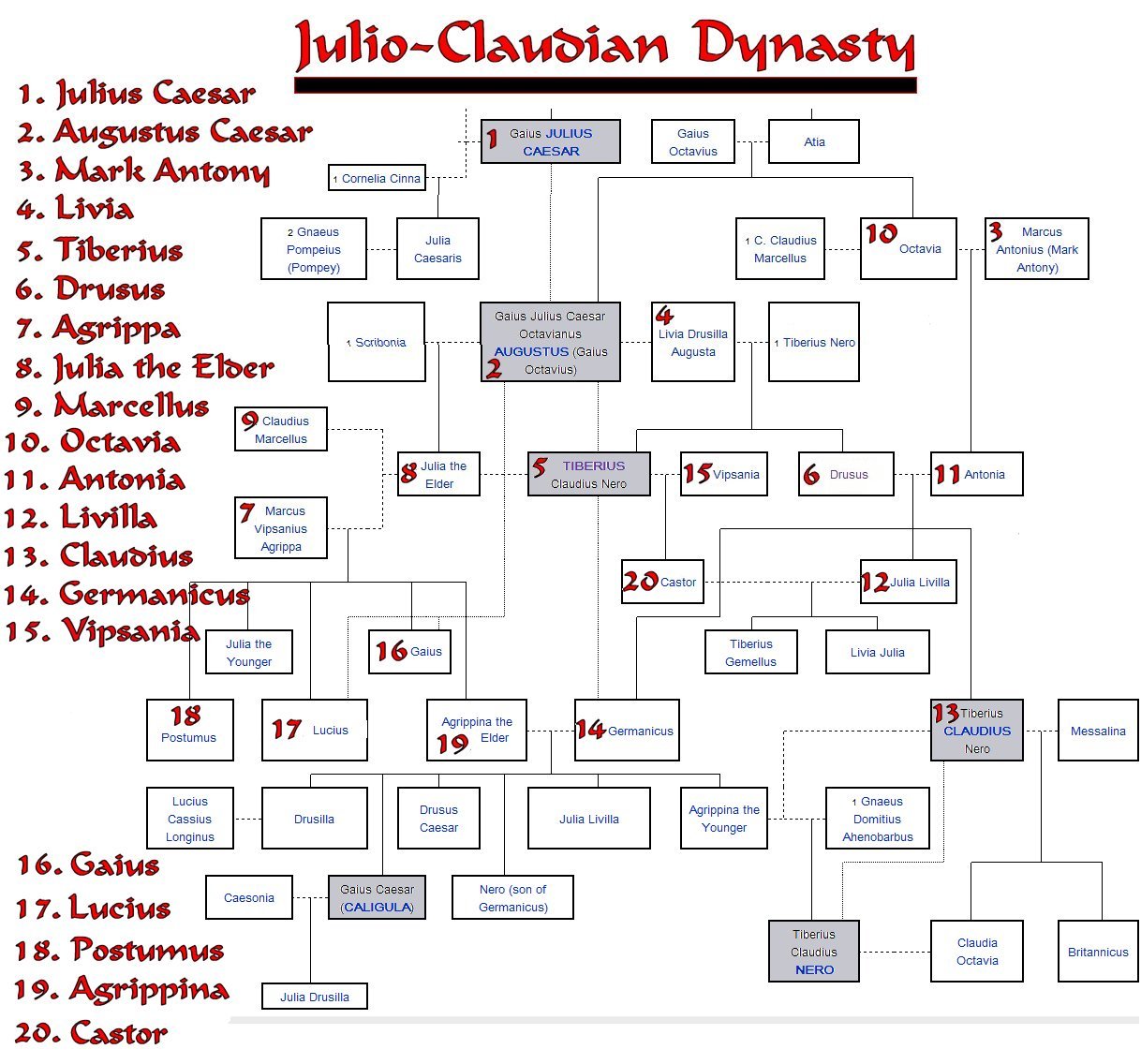

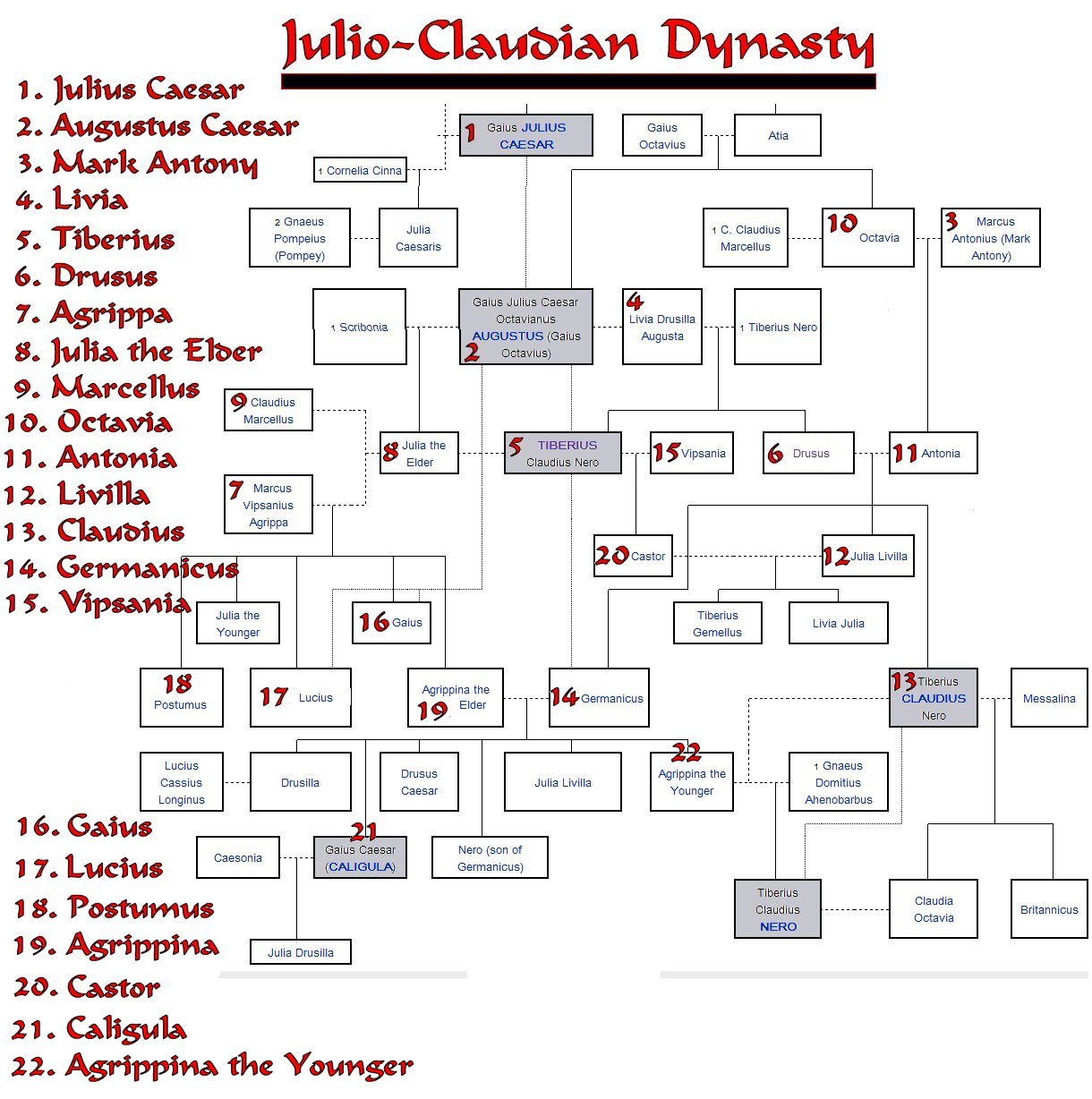

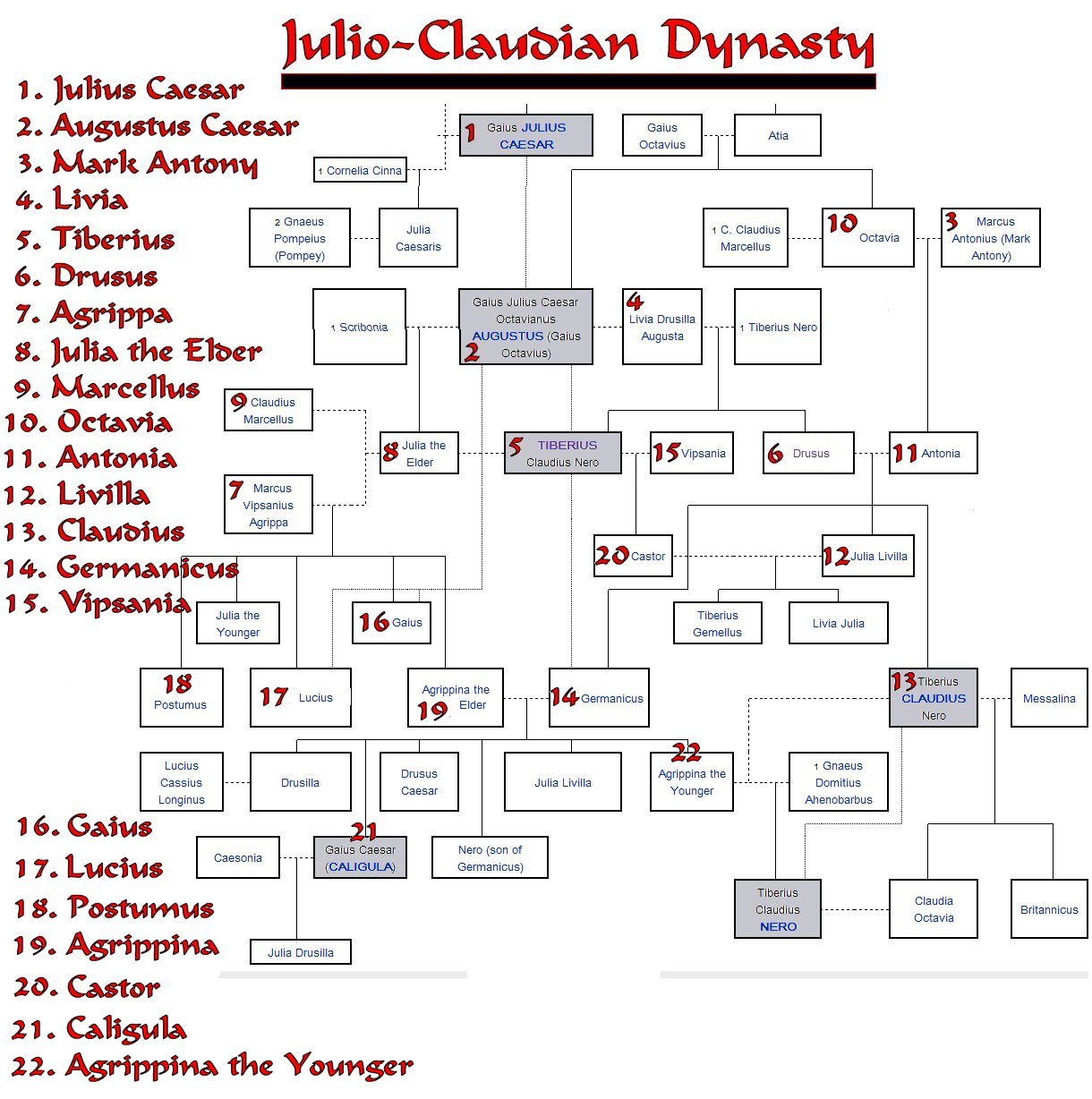

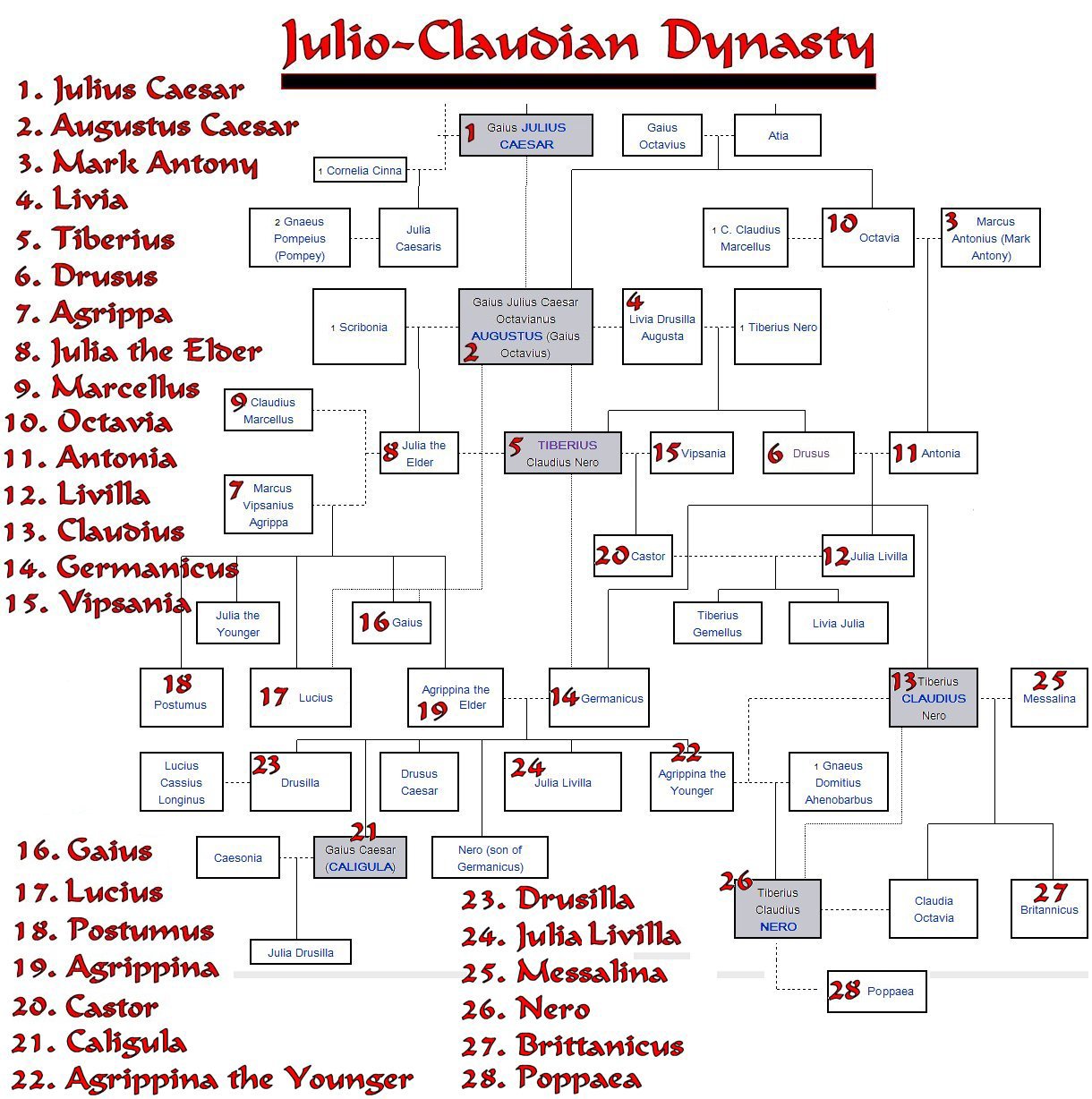

The

Julio-Claudian Dynasty

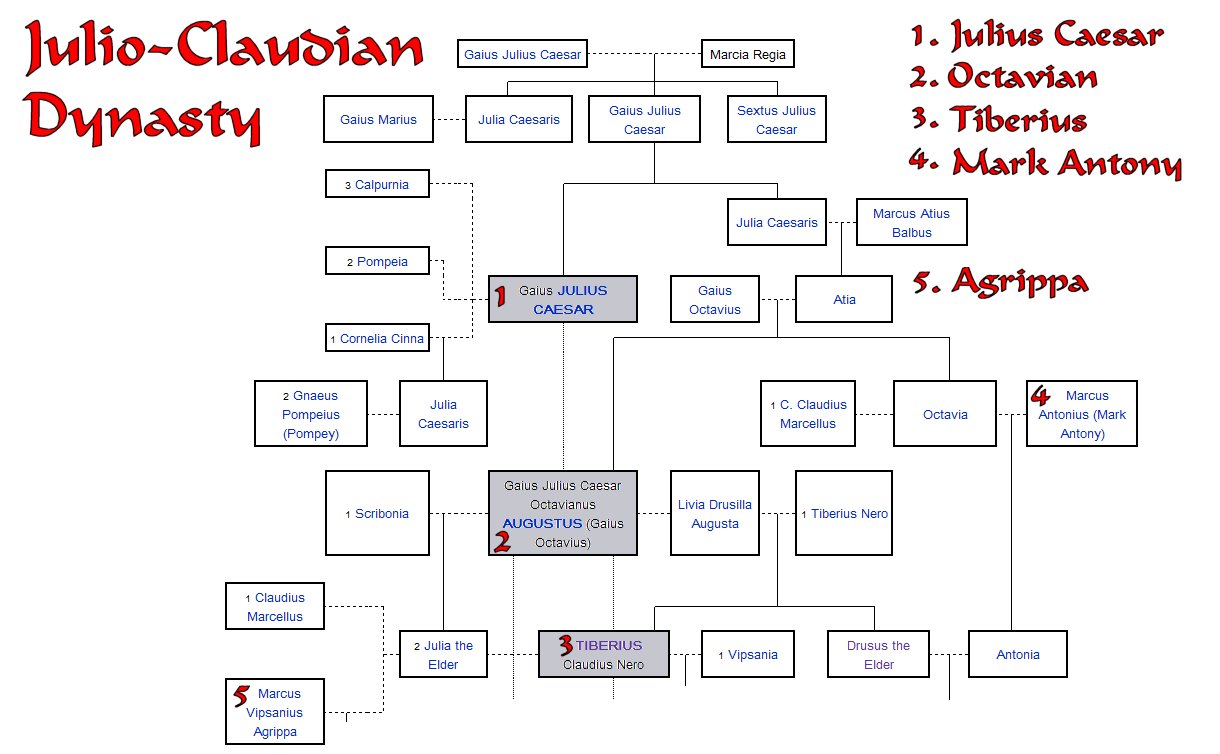

The term

Julio-Claudian Dynasty refers to the series of

the first five Roman Emperors. These men ruled the Roman

Empire from 27 BC to AD 68, when the last of the line, Nero,

committed suicide. The dynasty is so named from the

family names of its first two emperors: Gaius

Julius

Caesar Octavianus (Augustus) and Tiberius

Claudius

Nero (Tiberius). The ruling line was founded upon an

alliance between these two families.

The

5 Emperors of the Dynasty:

1. Augustus ( 27 BC– AD 14)

2. Tiberius (14– 37)

3. Caligula (37– 41)

4. Claudius (41– 54)

5. Nero (54– 68)

|

Chapter Three: Augustus Caesar

|

The Roman Civil Wars had

begun when

Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon

in 49 BC.

Now the wars were over. The death of Antony and Cleopatra in 30 BC

had brought twenty years of Roman Civil War to a dramatic

end.

In all, Octavian

had to eliminate over a dozen contenders to lay

undisputed claim the throne of Rome. This was quite an

accomplishment.

The time had come to crown Rome's

first emperor.

In 27 BC the Senate bestowed upon

Octavian the title 'Augustus',

meaning "revered". Augustus

would rule the Roman Empire for 45 years until his

death in 14 AD. During this

time, Augustus

Caesar would become Rome's greatest leader.

Under Augustus, Rome

would reach the

very zenith of power. Thanks first to the

groundwork of Julius Caesar and then to political

prowess of his talented nephew, the

Age of Augustus

became a time of lasting prosperity throughout the

Mediterranean.

|

|

| |

Augustus would

surpass his gifted predecessor Julius Caesar in

many ways. Although

Augustus had nowhere near the military ability of

his uncle, he was every bit the equal of Julius

in the area of politics. During his reign, Augustus

Caesar would bring social

stability to a region once plagued by constant

warfare.

One of the new emperor's main principles

was to persuade each defeated

territory to ally with Rome. Why not fight 'for

Rome' rather than against it? Talking

bitter enemies into becoming allies was never easy, but Augustus was good

at it. With German barbarians and Asiatic

hordes streaming into Europe, his promise of mutual

defense was a persuasive argument.

Although Roman leaders were

forced to extinguish occasional rebellions

such as the Great Jewish Revolt of 68 AD, the

interior of the Empire was left completely untouched

by civil war or attack by invaders from the

perimeter for 200 years.

Thanks to

his largely benevolent rule, Augustus established a

period of peace known as 'Pax

Romana' (Roman Peace)

that would last

from 27

BC till 180 AD.

There is little question that

Augustus made his uncle Julius proud. Augustus

built on what Julius started to create the greatest

Empire in ancient history.

|

|

In a lifetime spanning 77

years

(63

BC-14 AD),

one would think Augustus died a happy man, but such

was not the case.

Although Augustus Caesar

Augustus would go down as Rome's

finest Emperor, he would

suffer a very strange Destiny.

Indeed, over time the

most powerful man in the world would discover he was

virtually powerless within his own home.

The fate of Augustus was

highly ironic. Augustus

was

doomed to preside

over the most dysfunctional royal family of all time.

This awareness had to be

deeply painful for him.

In an age

when Roman debauchery made our own Swinging Seventies seem

tame, Augustus was determined to set a

good example as a moral leader. Augustus

strongly believed in 'Family'

as the bedrock of Roman society. He championed

virtue, marital faithfulness and the importance of

family values.

However, Augustus made one

very serious mistake.

Turning a blind eye to his

cherished family

values, Augustus stole another

man's wife. Little did he know his punishment would be a lifetime of neverending

personal tragedy.

Unlike Julius Caesar who had

picked a talented heir, Augustus would agonize over

his inability to

do the same. Despite his

best efforts, Augustus was unable to leave a competent heir to continue his

considerable legacy. It

must have driven him crazy.

According to

'I Claudius', it turns out there may have been a good

reason why Augustus Caesar did not leave a decent heir.

Her name was Livia.

|

|

| |

|

|

By marrying Augustus during his rise to power, Livia would

go on to become the first Empress of Rome.

Whereas Julius and Augustus Caesar

represented the 'Julian' side,

Livia provided the first 'Claudian' blood of the

Julio-Claudian family tree. Livia's father was a

member of the Claudian family and so was her first husband

prior to Augustus.

Born to

the Claudian family in 58 BC,

Livia's

first marriage at the age of 15 produced two sons, Tiberius

and Drusus. Tiberius, the future

emperor, was born in 42 BC, two years after the

assassination of Julius Caesar.

Drusus was

born in 38 BC.

Livia was

six months pregnant with Drusus when Augustus Caesar seized

her from her first husband and took her for his own wife.

Oddly enough, their marriage would be childless.

Their lack of children would have

grave consequences in every sense of the term. When it

came to blood, no one took it more seriously than Livia.

During her

52 year

career as Empress of Rome, she

would

elevate political assassination to an art form.

Livia

would live to the ripe of old age of 89,

a remarkable feat in an era when most people were lucky to

make it to 40.

|

| |

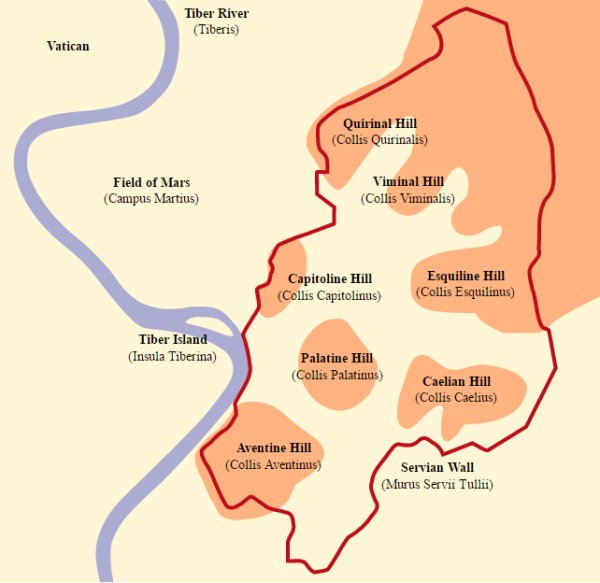

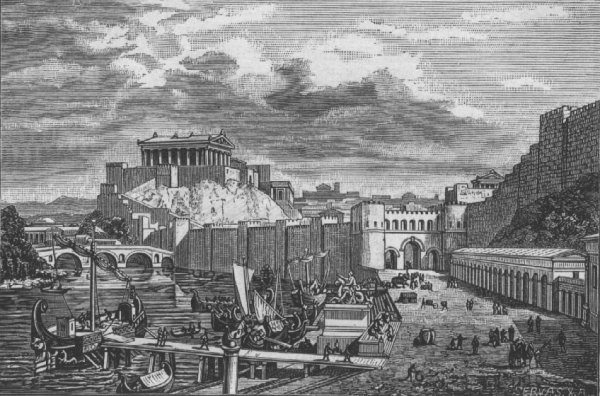

Disease was a huge problem in Rome. Built on top of a

swamp encompassed by seven surrounding hills, water did not

drain well. Malaria was a constant problem until

someone had the bright idea to build the Roman Forum over

the swamp.

Unfortunately, that did not stop the

disease. The early Romans had a bad habit of sending

human waste, garbage, and their corpses in the Tiber River.

Forced to drink badly-polluted water, the life span of the

average Roman was short indeed.

Livia was an extremely ambitious woman who likely

influenced the course of Roman history far more than most

people realize. Livia was the original power behind the

throne. At all times, Livia's opinions carried tremendous

sway over her husband's decisions.

It is said that Octavian fell in love

with Livia at first sight. This was an interesting

observation considered Livia was six months pregnant with

Drusus at the time. That didn't stop Octavian.

He waited all of three months until

Livia's second son Drusus was born

on January 14, 38 BC. Then

three

days later, Octavian married Livia. Livia was 20 at the time.

Married for 52 years, one has to

wonder if Octavian ever regretted his hasty decision.

Considering the damage and scandal Livia brought to his

family, one would assume so except for one thing... Livia

was the master of deceit.

For the rest of his life, Octavian had

no idea that his wife was the reason his heirs kept dying.

|

|

| |

Livia's

marriage to Augustus lasted until the day came when Livia

decided it was time to poison him as well.

At the root of the problem was their

childless marriage.

Since Livia and

Augustus had no children together, there was no consensus

heir. Augustus would have to appoint someone. Who would

become the

ultimate heir to the throne?

As Empress

of Rome, Livia decided she had every right to make her own

son Tiberius the next Emperor. It

was her decision to eliminate every possible rival to pave

the way for Tiberius that created 'The Roman Game of

Thrones'.

The British

mini-series 'I Claudius' offered compelling

circumstantial evidence that Livia was a serial killer

within the noble family. Robert Graves,

the writer, didn't just make his story up. Graves

based

his story on innuendo passed down by the Roman historian

Tacitus. Tacitus had portrayed Livia as a ruthless, scheming,

thoroughly Machiavellian political mastermind.

'I

Claudius' revealed that several untimely deaths and

plots were all the machinations of Augustus' cold wife

Livia. And you thought Queen Cerce in

HBO's 'Game of Thrones'

was the most evil woman of all? Guess again.

After

studying Livia's story from every angle possible, Graves

concluded Tacitus was not exaggerating. The Livia of

'I

Claudius' came across

as perhaps the most evil woman in history.

Livia's

systematic murder and scheming would

eventually eliminate every

talented man in the Julio-Claudian family tree.

Through her

actions, Livia personally doomed Rome to endure

the three

worst Emperors in Roman History - Tiberius, Caligula,

and Nero.

|

| |

|

Chapter Five: Julia and Marcellus

|

A young man named Marcellus was

Livia's first victim.

Augustus had

one child of his own.

Her name was Julia.

She was the daughter of Scribonia, Octavian's wife previous

to Livia.

Since Rome

frequently used marriages for political reasons, loveless

marriages were common. The story of

Scribonia was a perfect example.

Their marriage had not been a happy one.

Forced to marry Scribonia, a woman

15 years older than he,

Octavian felt she nagged him too much. Showing a

disconcerting lack of regard for the woman, Octavian

divorced Scribonia on the very same day she gave birth to

Julia the Elder.

So why was Octavian's daughter called

'Julia the Elder'?

Roman

history can be very confusing because there are so many

identical names. The Romans used 'Elder'

and 'Younger' the same way we use 'Senior' and

'Junior'. Another trick was to call someone's

mother 'Major' and the woman's daughter 'Minor'.

Since Julia

was inconveniently born a girl, by

Roman law she could not rule. This

irritated Augustus no end because he desperately needed a

male heir. Who would succeed him if he died young? Who

would succeed him if he died old?

One reason Caesar had

divorced Scribonia was in the

hopes that he and Livia would have children,

but that did not happen.

Fortunately Augustus was savvy enough

to create other options as well.

Roman law said that a male child had to be 14 in order to be

named emperor. Therefore Augustus needed

two heirs... a male heir

and

a caretaker

to rule until his male heir turned 14.

Tiberius was

always a possibility for the caretaker role.

However, Augustus did not care for the

boy. Tiberius was a very glum, moody kid. In

addition, Tiberius shared no blood with the illustrious emperor.

Augustus Caesar had this thing about bloodlines. It was his

preference to find someone who carried 'Julian' blood

for the caretaker role.

Tiberius was a 'Claudian'.

Fortunately Caesar knew

just where to look... his sister Octavia

(#10) had a strapping son

named Marcellus

(#9). Unlike Tiberius

who was totally Claudian,

Marcellus was half Julian and half Claudian.

Marcellus could become the caretaker in case

Augustus

died young. Furthermore, by marrying his daughter Julia

(#8) to

his nephew Marcellus, they could provide the male heir in

case he and Livia did not have a male child of their own.

This was the perfect solution. This

marriage would surely ensure his bloodline would

continue.

Julia

did not mind marrying her cousin.

As the daughter of the emperor, she knew how the game was played. Roman

Marriages served two purposes... to solidify alliances and

to provide heirs. As it turned out, Julia actually

liked her husband. And why not? Marcellus was

smart and ambitious. Julia expected her husband would

one day be the next Emperor and their first son would be the

Emperor after that.

Immediately

after his marriage to Julia in 25 BC, Marcellus was chosen

by Augustus to serve with him in Hispania alongside cousin

Tiberius. During this campaign Marcellus excelled.

Augustus was thrilled to see what a wise choice he had

made to marry his daughter.

As for the caretaker role, Augustus developed a clear

preference for Marcellus, his nephew, over his gloomy

stepson Tiberius.

Augustus had

found his man. Augustus named

Marcellus his immediate successor. Marcellus was now in direct line for the

throne and so would be his children.

Unfortunately, there would be no children. Once Livia

realized her son Tiberius was frozen out of the succession process,

she refused to sit idly by. Livia took matters into her own

hands. She poisoned Marcellus two years into the marriage.

Taking her time, Livia did it so

skillfully that only a few eyebrows were raised. It is

important to keep in mind that people died all the time in

ancient Rome and no one was ever quite sure what the cause

was. Between the malaria and the tainted water,

disease was so common that only the most incompetent

poisoners risked getting caught.

Now Julia was a widow. And childless...

Augustus was forced to start looking for

another successor.

|

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa was a hero of Rome. Agrippa was

responsible for many important military victories, most

notably at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC against the forces

of Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The

direct result of these victories

allowed Octavian

to become the first Roman Emperor, adopting the name

of Augustus.

Agrippa

(#7) was born in 64 BC.

His family had not

been prominent in Roman public life, so

Agrippa chose the military over a political career.

Agrippa was about the same age as Octavian,

so the two were educated together.

They became close friends.

Augustus and

Agrippa had great respect for one another. Augustus trusted

Agrippa implicitly.

After the war, Augustus gave his friend Agrippa many duties

running the government. Indeed, Agrippa oversaw the

construction of some of the most notable buildings in the

history of Rome.

Unfortunately,

in 25 BC, Agrippa

got his nose bent out of shape. He

was miffed that Augustus had chosen Marcellus, a mere pup,

over him for the 'Caretaker' role. Agrippa was by

far the better choice to run the government in case Augustus

died young.

Agrippa's

friendship with Augustus seems to have been clouded by his

jealousy toward Marcellus. This rift was instigated by the

intrigues of Livia who feared Agrippa's

considerable influence over her

husband. She whispered that Marcellus had the right blood

and Agrippa didn't. This was an odd

thing to say since she later poisoned the lad.

Augustus was

unable to find a delicate way to explain the 'blood' thing to Agrippa.

Things became awkward, so Agrippa chose to head over to Asia

Minor for a while and nurse his hurt feelings.

|

|

| |

When

Marcellus turned up dead at age 19, Augustus

interpreted this as a sign from the Gods that

he had made the wrong choice to begin with. He should

never have overlooked Agrippa in the first place.

Augustus decided it

was time to hand the Caretaker role to his best friend. So

Agrippa got a phone call... "Get your ass back to Rome!"

While

waiting for Agrippa's return, Augustus had a great idea.

Why not marry Julia to Agrippa? So what if the man was old

enough to be her father? Yes, indeed, despite the 25 year

age difference, Julia was told wed to her father's loyal friend.

Augustus gave his daughter one word of advice... "Reproduce!"

Julia took

her duty seriously. Agrippa soon discovered that Julia

liked sex. In fact, she liked it a lot. Agrippa was 43 when he

married Julia in 21 BC, but he somehow

managed to give her five

children, including three boys, in the space of nine years.

Impressive!

Agrippa died

at the age of 52 in 12 BC. His death was attributed to

natural causes, but my guess it was more likely from an

overdose of sex.

No doubt Julia took ten years off

the man's life by bedding him constantly.

Meanwhile,

upon Agrippa's death,

Julia was a widow for the second time.

|

| |

|

Chapter Seven: Drusus and Tiberius

|

After the death of Agrippa in 12 BC, Tiberius and his

younger brother Drusus were named co-heirs to the throne of

Augustus.

Tiberius was

a dark, brooding man who in many ways was

reminiscent of

Richard Nixon. Like Nixon, Tiberius was an intelligent man

with talent. In particular, he was a good military leader.

However, due to the strange twists and turns of his personal

life, over time Tiberius would turn into a truly evil man. Tiberius was increasingly disliked due to his abuse

of power.

Like Nixon,

Tiberius was

a man with no tolerance for criticism.

The more

people disliked Tiberius, the meaner he got.

Drusus

(#6) was

Tiberius' best friend in the world.

Drusus

was unbelievably talented. Unlike his moody older brother,

Drusus was loved by all. He was a brilliant general and a

skilled fighter who demonstrated great courage. Rather than

watch his battles from safety,

Drusus regularly engaged the Germans in hand

to hand combat.

In addition to his military success,

Drusus was a

respected family man. He was married to Antonia

(#11), the step-sister

of Julia's

poisoned husband Marcellus. Antonia was the daughter of Mark

Antony (#3). Her mother was Octavia

(#10), the sister of Augustus. Antonia was the favorite niece of Augustus Caesar. Augustus

adored Drusus, Livia's son, as well.

Drusus and

Antonia had three children: Livilla

(#12),

Claudius (#13), and

Germanicus

(#14).

A person would be challenged to find

three more different children.

Germanicus

would one day turn out to be a military hero just like his

father. Livilla would one day become Livia's partner in

crime. As for Claudius, everyone thought he should have

been thrown to the wolves at birth. This

weakling

was a clumsy, stuttering, half-witted fool.

No one could have ever dreamed Claudius

of all people would become Rome's fourth emperor.

As for their father

Drusus, not only was he a true Roman

war hero, he was

one the few truly decent husbands around. As a proponent of

family values, Augustus was proud of Drusus for being loyal

to his wife and a great father. Drusus and Antonia

became the

favorite couple of Augustus. If forced to choose between

Tiberius and Drusus to succced him, there was no doubt that Augustus would

have chosen Drusus.

This was a certainty that bothered Livia no end.

For reasons no one could decipher, Livia favored Tiberius

over Drusus. Livia was probably the only person in

Rome who would have chosen Tiberius over Drusus. After

all,

Drusus was a gifted man, far superior to his moody brother

as a leader.

Livia's

preference for Tiberius led her to make a strange decision.

It is

difficult to conceive of a situation where a mother would

willingly allow a son as noble as Drusus to die, but

apparently that is exactly what Livia did.

The only explanation that makes any sense was

the threat Drusus presented to the Imperial throne.

Livia did not trust Drusus. Livia had

intercepted a letter from Drusus to Tiberius. Drusus had

written his brother to express his desire to eliminate the Imperial tradition.

Drusus was deeply committed to the return of Rome to a democratic Republic. In his

letter, Drusus explained his preference for a state in which

supreme power is held by the people and their elected

representatives. He strongly advocated having an elected

president rather than a monarch.

Livia shook her head in horror. Her entire life was

wrapped around supporting the Imperial system and now her

own son wanted to put an end to it.

As long as Drusus lived, Tiberius would never be emperor.

Livia knew that if Augustus

died, Drusus would inherit

the reins of power instead of his older

brother. At this point, she was convinced that Drusus would return

Rome to being a Republic. Livia

understood that Drusus had the

charisma to pull this off. Livia also understood that

Augustus loved Drusus so much that it would be too risky to

share her suspicions with her husband.

Augustus loved Drusus so much that he

would never believe her.

Given a

choice between backing her husband and

older son or backing her youngest

son, Livia sided with Tiberius.

For Tiberius

to ever have a chance to become emperor, it would be

convenient if Drusus disappeared. And that he did.

It was Livia's way to eliminate all

threats to the throne, even if it was her own child.

So when the opportunity arose in 9 BC,

Livia took advantage to cause the death of Drusus.

Livia didn't actually murder Drusus, but she

did make sure her son would fail to

recover from a dangerous

injury.

Drusus fell

off his horse in battle and badly injured his leg. When

Livia learned of her son's distress, she sent her personal

physician to the battle front with instructions to do

little to help the man recover. Since Livia's

explicit orders gave her personal physician

rank over the attending physician, her

crony was able to carry

out her wishes. Once gangrene set in, Drusus was a

goner.

Off fighting

on the Danube, Tiberius rushed to the side of his dying brother

the moment he heard. It was too late. When he was informed

of the doctor's

suspicious behavior, Tiberius had to

be restrained from killing the physician on the spot.

Tiberius

knew how his mother felt about Drusus and became suspicious

that she had meddled. This incident was a major step in

Tiberius' growing hatred towards his mother. Little

did Tiberius know that his mother was just getting started.

|

Livia's stated purpose in life was to advance Tiberius to

the throne. No obstacle was too great. To date,

Livia had eliminated Marcellus, the prime candidate to

succeed Augustus, as well as her own son Drusus, the most

popular man in Rome after Augustus.

Following the death of Agrippa in 12

BC, Livia was upset

because her plan wasn't working. Although

Livia had

been able to get rid of Marcellus, Julia's first husband,

this move had badly backfired on her. After the mysterious

death of Marcellus, Julia had become available. Mending fences

with his old friend, Augustus suggested to Agrippa that he

marry his daughter Julia and become his declared successor.

Agrippa was

one of the few obstacles that Livia could not eliminate.

Much to Livia's dismay, Julia turned out to be unbelievably

fertile. Julia bore five children including three boys who

would become direct heirs to her father's throne over

Tiberius because they shared the all-important Julio-Claudian

bloodline. With each new

birth, Livia died a million deaths. Who could have

imagined Julia could reproduce heirs faster than Livia could

kill them?

Right now there was nearly an entire

basketball team of heirs growing up at the Imperial Palace

thanks to Julia's super-human sex drive.

Consequently

Tiberius was now at best fifth in line for the throne.

What was Livia to do?

As the only child of the Emperor, Julia

(#8) had every privilege

a woman could hope for. It did her no good.

Princess

Julia was born to live a tragic life.

Earlier we learned that Julia was born to Scribonia, Augustus' first wife, on the

same day that Augustus divorced her mother. Talk

about a bad omen! Three days

later, Livia became Julia's stepmother. Despite a 19 year

difference in ages, Julia and Livia would one day become

bitter rivals. Livia was the last

person Julia wanted to tangle with.

When Agrippa

died in 12 BC, Livia saw an opportunity. The longer

Augustus lived, one of Julia's boys would become

old enough to be his successor. However, in the short term, Drusus and Tiberius

were the most likely candidates to succeed Augustus until

the boys came of age. Drusus was

still alive at this point. So, how could Livia promote Tiberius

over Drusus? And, for that matter, how could Livia promote

Tiberius over Julia's sons by Agrippa?

Livia thought she had the answer.

Julia was a

widow for the second time. Noting that Marcellus and

Agrippa had been in line to become Augustus' successor,

Livia realized that if Tiberius married Julia, that would

fast-track Tiberius to the become the next heir in line.

Tiberius could then promote any male children from his

marriage to Julia over the male heirs from Julia's

previous marriage

to Agrippa.

Livia

reached the obvious conclusion. TIBERIUS HAD TO MARRY JULIA

AT ALL COST!!

On paper,

this was correct thinking. Although

Julia and Tiberius had grown up together in the same

household, since they had no blood in common, they were

technically able to marry. Nevertheless,

this was a terrible idea.

Livia must have known there was at best only the most remote

chance this plan would work.

First of

all, Julia had always

looked down on Tiberius. Tiberius, the thin-skinned,

unloved kid, knew full well that his step-sister Julia felt

he was inferior. He had resented

her tendency to belittle him ever since they were kids.

Second, who wants to marry their sister, even if she is a

step-sister?

However, we haven't even touched the real problem. Besides Drusus, Tiberius

had one other friend in the world. Her name was Vipsania

Agrippa. Tiberius was deeply in love with Vipsania.

So who was

Vipsania Agrippa? Vipsania Agrippa was the daughter of Julia's deceased

husband Agrippa by an earlier marriage. One

more thing... Vipsania was

Tiberius's

wife. Furthermore, Tiberius wanted to keep it that

way. He loved this woman.

Adding to Tiberius' exasperation,

Vipsania was pregnant with Tiberius' first child!!

As one might imagine,

Tiberius was

aghast at his mother's idea.

Did his mother really want him to divorce the

woman he loved in order to marry his step-sister,

a woman who could

barely tolerate him?

Did his

mother really expect him to divorce the gentle daughter of

the deceased Agrippa, the mother of his

unborn son, to marry the

shrew-like wife of the deceased Agrippa?

"Yes, son,"

Livia replied, "that is exactly what I want you to do.

Do your duty."

Livia's

reasoning was simple. If she could abandon her

first husband to

advance her own social standing, then she expected her son

to do the same.

Tiberius

didn't agree. He said the two situations were not

equal. Tiberius loved his wife dearly, but his mother

had not loved her husband. His

mother was nuts if she expected Tiberius to leave his best friend in the world.

How would he ever be able to look

Vipsania in the eye and explain this?

Tiberius

rebelled. He said he wouldn't do it.

Livia didn't care. She simply

convinced

her husband to order Tiberius to submit

for the good of the Empire whether he liked it

or not. Augustus wasn't so sure about this, but Livia was

relentless. Finally Augustus gave in. Emperor Augustus

ordered his stepson to marry Julia, his recently widowed

daughter, in order to secure the imperial succession.

Meanwhile, Julia wasn't one bit happy

about this idea. Did her father actually expect her to

have sex with such a repulsive man? Augustus replied,

"Yes, Julia, we need as many male heirs in this household as

possible."

Based on Roman law, neither

Julia nor Tiberius could refuse.

Consequently the marriage was shoved down their

throat. Completely against their will, they

were married in 11 BC. Tiberius was now

named the direct

successor to the throne.

So now we

know how Tiberius became emperor, right? Wrong. Livia's

plan backfired horribly.

The entire

idea was hopeless from the start. The spoiled and

sharp-tongued Julia was hardly a model replacement for the

demure and dutiful Vipsania.

Resentful at being forced into this stupid marriage, she

took her anger out on Tiberius. Treating Tiberius with

contempt, Julia cut this proud man to shreds with her

constant criticism. Plain and simple, Julia compared

Tiberius to her first husband Marcellus and

her second husband Agrippa.

She made it clear Tiberius would

never be the man that they were. In

other words, Tiberius wasn't good

enough for her. Why had she ever

agreed to this?

Trapped in a

horrible marriage, Tiberius missed his discarded wife

Vipsania terribly. He started to see her again secretly

even though he knew it was forbidden.

When Augustus found out... thanks to Livia, of course... he

banned Tiberius from ever setting eyes on his first wife

again... or else. Tiberius was forlorn.

One year into the marriage, Julia bore Tiberius a son. Unfortunately the child died in

infancy. That was the last straw for Julia. She was sick

and tired of being treated as little more than a baby

machine for the Roman Empire. Julia refused to ever let

this man touch her again. Julia went to her father and

said she had done her best, but this wasn't going to work.

Julia

demanded he send Tiberius to war, preferably some place

dangerous where a barbarian might stab the man to death.

With a heavy heart, Augustus sent Tiberius to the Danube

region.

While

Tiberius was off fighting the Germans, in 9 BC he learned

that Drusus was dying. The combination of the failed

marriage and losing Vipsania was tough enough.

Now losing

Drusus was more than he could bear. Lost in the grips of

despair, Tiberius began drinking heavily.

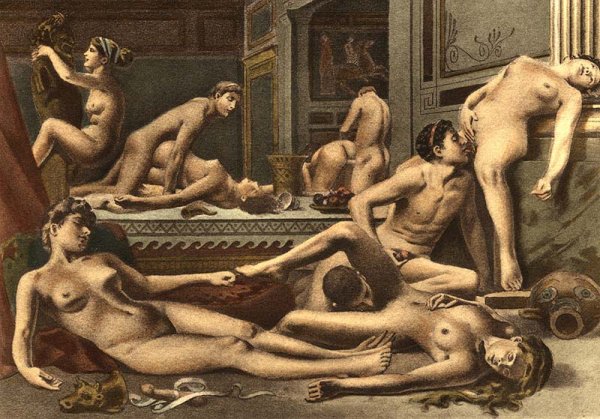

Meanwhile,

back at home, the moment Tiberius was gone, Julia took full

advantage of his absence. Julia turned into a predatory,

drunken nymphomaniac. She once gave herself to a lover on

the sacred speaker's rostrum of the Forum. Julia developed

a particular fetish for dwarfs. She made sure one

accompanied her wherever she went and demanded he satisfy

her on the spot whenever she was in the mood.

When

Tiberius returned from fighting Germans in 7 BC, he discovered his house

was being used as a brothel. He was dismayed to learn his

wife's outrageous behavior was the talk of Rome. Tiberius

was fed up. He

didn't want to have anything to do with Julia or Rome. To

hell with being emperor. Publicly humiliated by his wife's

antics and disgusted with his mother and stepfather,

Tiberius resigned his military position. He took the

next ship out of Rome for Rhodes, an island off the

southwestern coast of Turkey and began a self-imposed

exile. Tiberius was a broken man.

Julia could

have cared less. She despised Tiberius. For that matter,

she hated the world and she hated her

lousy fate. She hated her father for forcing

this awful man on her. She hated her stepmother Livia

for interfering in her life. Julia was tired of being

told what to do. First she lost the

man she loved, her cousin Marcellus, at

age 14.

Then she was forced to wed her father's elderly friend Agrippa at 17

in a

loveless diplomatic union. She had

done her duty and

given the

Empire three perfectly healthy boys to be trained as heirs.

Then to top it off, she had agreed to this ridiculous

marriage. Her disgust knew no bounds. What a farce this

marriage was. She was tired of

being treated like a piece of property, so now she openly

defied her father by demanding a divorce.

After

Tiberius' departure to Rhodes, her father granted her

wish. Free at last, petulant Julia continued pursuing a

life of hedonistic abandon. It doesn't take a degree in

Psychology to see Julia was in the process of saying 'F...

You' to Livia and Augustus.

| |

|

Julia was

done taking orders. She was going to do things her way

from now on. Julia was extremely beautiful and graceful, so

she could have as many men as she wanted. She was unable

to control her nymphomania and no one had the authority to

stop her for her own good... except for her father.

However, that

wasn't likely to happen because Augustus

had no idea what was going on. No one dared tell Augustus

what his crazy daughter was up to.

Julia

admitted lovers to her room in droves and participated in

nightly orgies throughout the city. Then she branched out

into having sex in broad daylight. She conducted daily

public meetings beside the statue of Marsyas, a Phrygian

Satyr who invented the music of the flute. Julia would

survey the men as they passed by and claim any man who

struck her fancy. Few men dared refuse the daughter of the

Emperor.

It was now 2

BC. Five years had passed since Tiberius left for Rhodes.

Amazingly, Augustus was still in the dark. Roman historian

Seneca reported that while Julia continued to bring enormous

scandal to the imperial home, her own father remained

completely oblivious.

Livia, on

the other hand, discovered what was going on. She sensed an

opportunity. Livia blackmailed one of Julia's countless

lovers. Did this young man really want to face her husband

the Emperor and confess his crime of adultery? Or would he

rather simply compile a list of some of the men Julia had

slept with?

When the

list grew long enough, Livia found a way to get a family

member to break the story to Augustus. Livia knew better

than to let her husband know her own fingerprints were all

over this ploy.

Livia had

already guessed what Augustus would do. Sure enough, her 'family

values' husband Augustus was incredibly upset. Julia

had to be punished for her excessive debauchery. Reluctant

to execute her, Augustus decided instead to exile his

headstrong daughter.

In 2

BC, Julia was confined on the small island of Pandateria.

|

| |

There were no trees on the rocky isle.

There were no men in sight. Julia was

forbidden to even to drink wine. Left alone with only her

diseased mind for company, this island became Julia's living

hell.

At first,

Livia was thrilled. Julia had been a thorn in her side and

was a constant threat to tell her father of her growing

suspicions about her stepmother's secret acts. Now Julia

was gone. Good riddance!

However,

in the meantime, Livia's campaign to make Tiberius emperor was blown to

pieces. And it didn't look like

Tiberius would ever get another chance. After banishing his daughter to a remote island,

Augustus held Tiberius directly responsible for his

daughter's shameful behavior. Augustus

told Livia he didn't want anything to do with

Tiberius ever again.

Livia was

fit to be tied.

Given her

husband's dark mood

plus all

of Julia's little brats running around

the palace to make her life miserable, how would

Livia ever make her son the emperor?

It seemed impossible.

But don't ever underestimate Livia...

|

|

Chapter Nine: The Curse of the Imperial

Palace

|

At this point, Tiberius had no chance of becoming emperor.

The two men despised each other.

Making

matters worse, Julia's three sons were growing up. These

were Agrippa's sons. In the eyes of

Augustus, these boys carried the intelligence of the

great general and the precious royal

blood of his exiled

daughter. The boys were smart as a whip and very

ambitious. Now that their mother

had been sent away, Augustus became

their surrogate father. He poured his heart and soul into

training these young men. He taught

them military strategy and

politics every chance he got. Augustus was content. He had

three competent young men in line for the throne.

What was

Livia to do? Fanatically devoted to bringing her son

Tiberius to power, Livia had a steep hill to climb. Livia was undaunted. Years before, she had poisoned

Marcellus, Julia's first husband and Augustus Caesar's

choice as heir. Now she turned her evil eye to the three

boys. She decided to eliminate the boys one at a time.

In 2 AD, one heir - Lucius (#17) - was thrown overboard at sea by

the same man Livia had blackmailed to betray Julia.

Eighteen months later another heir - Gaius

(#16) - died

mysteriously in battle.

Augustus was

in shock. How was it possible for any man to have such bad

luck? Why did the Roman Gods view him with so much

disfavor? It

seemed like he was plagued by one personal loss after

another. August had now lost five heirs... Marcellus, Agrippa,

Drusus, and now Agrippa's sons Gaius Caesar and Lucius

Caesar.

In a sense,

he had also lost Tiberius, but that was no great loss. On

the other hand, now that two of Julia's

three boys were gone,

maybe he should reconsider Tiberius. Nine years had passed

since the divorce. Julia was gone now, so maybe Tiberius

should be reinstated. After

all, Tiberius had done nothing wrong. So the marriage

failed? Given his daughter's scandalous behavior,

maybe Tiberius deserved another chance.

There were

only two possible heirs left. One was Postumus,

14, Agrippa's

youngest son of three. And of course Tiberius,

44. Due to all these deaths, Tiberius

was actually the only man left standing who

had the

experience to run the Empire. Augustus was 67. This was no

time to be picky.

Although

Augustus greatly preferred Postumus as his successor, the

boy was only 14. He was too young and too wet behind the

ears. If something were to happen to Augustus, at least

he was comforted by the fact that Tiberius had been a good general. Reluctantly the aging

Augustus summoned Tiberius back to Rome. At this point

Augustus made Postumus and Tiberius co-heirs.

Postumus

(#18)

immediately began quaking in his boots. Postumus was well

aware of the Curse of the Imperial Palace.

Losing his two brothers really had him spooked. The boy confided

to a friend that surely he would be the next to die.

Sad to say,

the boy was right. Five years later, in 9 AD, Postumus was

gone.

So what happened to Postumus? He

ran into a shrew-bitch named Livilla.

So who was

Livilla? Livilla (#12) was the daughter of Drusus, the one who

died of gangrene in 9 BC. Losing her father at age 4,

Livilla had grown up without much

guidance. Livilla had grown up to be a wild

child brat.

No one could

tell her what to do.

Livilla

married her cousin Castor (#20), Tiberius' only child by his first

marriage to Vipsania. Castor had suffered from the same

neglect as Livilla. Growing up in his mother's home, Castor

had virtually no relationship with his father Tiberius. He

turned into a moody, resentful bully just like his father.

Castor was no prize... but neither was Livilla.

They were both lowlifes.

Livilla

couldn't stand her thug-like husband

Castor. So she started an

adulterous affair with the handsome Postumus, her distant

cousin. Livia picked up on it. Livia threatened

Livilla she was about to reveal

the affair to Augustus. Did Livilla really want to go live

on a wind-blown rocky island like Aunt Julia? Livilla quickly

caved in. She agreed to entrap Postumus in exchange for her

freedom.

The next time Postumus entered her room, Livilla

let the young man get most of her clothes off before

screaming "Rape!" at the top of her lungs.

Guards came

sprinting and witnessed Postumus as he

stripped Livilla

naked. Caught red-handed, Postumus never had a chance. He

knew he had been set up, but what could he do? The Curse of

the Imperial Palace had struck again. Down went another heir. With a heavy heart, Augustus sent Postumus into exile

on some lonely island.

Rumors

abounded that something wasn't quite right. Since when had

a tramp like Livilla refused any man,

much less a stud like Postumus? All the

men had to do

was knock. Even Augustus was unsure. Augustus began to

suspect he may have been too hasty sending Postumus away.

Augustus was always the last one to know,

but now even he grasped there was something fishy going on

inside the Imperial Palace. He made a secret trip to see Postumus on his island and perhaps clear the air. Postumus

told Augustus that he believed Livia had been killing those who could

prevent Tiberius. This was way too much for Augustus to

believe. Nevertheless, Augustus promised to petition the

Senate to allow the boy's return.

Once Livia

learned of the secret meeting, her sixth sense warned her

that trouble was brewing. There was a strange look in her

husband's

eye. She decided it was time for

August to go.

Why wait? After all, Tiberius was in position to take

over. So Livia began to rub aconite, better known as wolf's

bane, on the figs ripening in her husband's beloved fig

grove. In 14 AD, Augustus died. He was 75.

Tying up

loose ends, Livia's next step was to send an agent

named Sejanus to murder

Postumus on his island. There was no one left to oppose

Tiberius.

With the

death of Augustus, Tiberius took control. Rome was saddled

with a leader who had been turned by his mother into a

deeply bitter man. Needless to say, Augustus Caesar's

decision to turn the Empire over to Tiberius was

ill-advised, but what choice did he have?

|

|

Chapter Ten: Agrippina and Germanicus

|

| |

|

The 9 AD

Battle of Teutoberg Forest was the worst defeat in Roman

history. Three Roman legions had been ambushed in a remote German

forest thanks to the brilliant deception of a traitor

named Arminius. Arminius led the Romans deep

into the German forest straight into a

well-executed trap. A three day

slaughter at the hands of the barbarians

left not one man standing. The result

was a staggering loss of

25% of the entire Roman

army. Proud Rome was deeply

humiliated.

In 12 AD, Germanicus had led

Roman troops deep into Germania to avenge

the bitter Roman defeat at Teutoberg. Following his

decisive victory, Germanicus was a

supreme hero. He became known as 'The Roman

Alexander the Great'. Germanicus

grew to become

the most respected man in the Empire.

A majority of the Roman people strongly preferred

Tiberius' nephew Germanicus as emperor over cruel

Tiberius. Why wait for Tiberius to die? Germanicus

would do just fine!

This situation

had been festering for several years.

Tiberius, always the

paranoid one, believed he could be

assassinated at any moment.

Therefore he monitored the Germanicus situation

closely. Tiberius really didn't know what to

do. After all, Germanicus (#14) was his

nephew, the son of his beloved brother Drusus (#6).

Tiberius was reluctant to take action.

|

|

| |

|

Germanicus

was married to

Agrippina (#19). Agrippina was one of five

children born to Julia and Agrippa, the military genius who

was once the closest friend

of Augustus. Augustus loved

his granddaughter Agrippina

dearly. He was proud of her for giving birth to six

children. He Agrippina the Younger (#22), Lucius, Drusilla,

Drusus, Julia, and a strange kid named Caligula.

Augustus wasn't so sure about Caligula (#21). Noting

his bizarre tendency to crawl naked into the beds of his

three sisters, Augustus (and others) concluded there was

something not right about Agrippina's youngest son.

Augustus was equally proud of Germanicus,

34. This fine young man had become the spitting image of his amazing

father Drusus. Germanicus was not only

a brilliant general,

Augustus respected the man for paying

close attention to his wife and family.

Together Germanicus

and Agrippina and their six children

formed the shining light in the last years

of Augustus Caesar's life. Augustus had often expressed to Livia his

hope that Germanicus would one day succeed Tiberius as

emperor. Livia frowned every time

she heard that. The way Livia saw it, Germanicus was a real threat

to do just that. The only question was when?

After Augustus passed on in 14 AD,

Livia watched with concern as the popularity of Germanicus

grew by leaps and bounds. Livia knew full well the mob

wanted her gloomy son replaced with this hero. All

they needed was an excuse.

There was no love lost between Livia and Agrippina. Livia

was well aware that Agrippina hated her.

Livia knew that Agrippina suspected

that Livia had been behind the plot that sent her mother

Julia (#8) into exile.

Livia also knew that Agrippina had grown

into a dangerous rival. It was hard to predict whether

Agrippina would foment rebellion and try to propel her

husband to unseat Tiberius or simply attend to raising her

family.

Agrippina

was a savvy woman indeed. Agrippina had grown up in the Imperial

Palace and had heard all the rumors about

the Curse. Agrippina needed

no convincing. She knew the Curse was real. She had

witnessed her mother being sent to exile in 2 BC

never to be seen again. Agrippina had been there when

her two brothers Lucius and Gaius had mysteriously died on

military missions. Agrippina had watched in horror

when her brother Postumus was

shipped off to a deserted isle

on trumped up rape charges never to be seen again.

Agrippina had watched as her hale and hearty grandfather

Augustus had mysteriously taken ill and died

soon after. In other words, Agrippina had seen it all. Agrippina

had her suspicions who was responsible

for all these mysteries and thus was on constant guard.

In the

five years

since the death of Augustus, Tiberius and his henchman

Sejanus had ruled Rome with an iron fist.

Although Tiberius was an able

administrator, the Emperor had become widely hated in

the process. Tiberius and Livia both

knew all Germanicus had to do was snap his fingers to

create an uprising. However, so far

Germanicus had been a true patriot like his father

Drusus. Rather than stir up

trouble, instead Germanicus