Creating the Canal 1

Written by Rick Archer

October 2011

|

|

Creating the Panama Canal

Have you ever wondered how

they made the Panama Canal? Most people - and that

includes me - assumed they dug an enormous 50 mile trench

across the Isthmus of Panama. In fact, that was the

original plan - dig dig dig till the oceans connected.

Call it the "French Connection".

Many people do

not realize the French tried first. The French began work on a Panama Canal of their own back in

1880. They stayed with the project for 10 years until they

gave up in utter futility. The Americans had been

following the progress of the French closely. The USA

wanted that canal built in the worst way. But if they

took over the project, could they do any better?

When it was

proposed to build the Panama Canal there were those who

believed it was possible to cut down the backbone of the

Cordilleras until the waters of the oceans could sweep

through unhindered to a depth which even at low tide would

carry the largest steamship afloat. The "Dig Down"

concept was at the core of the French Connection Plan.

There were

others who held that a more feasible plan would be to lift

up the waters. This alternative plan was to raise the waters in

the middle of Panama to an

elevation as high as 85 above sea level. Then they

would lift the ships

to meet them using a lock system. The latter idea prevailed.

The American people owe their

triumph at Panama to this bold gamble.

|

|

The

French Plan... aka Dig Dig Dig... had called for

excavating the entire 50 mile stretch.

The Americans

proposed to connect the bend in the Rio Chagres

(see map) with

the Miraflores Lake by creating a giant gap in the

mountains. The American "Raise the Waters" plan

meant they only had to dig about one-fifth of the

way... 10 miles or so.

After

that, the Americans would raise the waters.

What exactly did that mean? How do you "raise

the waters"? Keep that in the back of your

mind; we will get to it later.

The

American plan was still a heck of a lot of work. They had to carve a gap

one-third of a mile wide and 120 feet deep through solid

mountain rock. It was the modern-day equivalent of

creating a replica of the Grand Canyon down in Panama.

The Grand Canyon took eons to create. How long would

it take humans to do it and was it even

possible?

In this case, it

really was nearly impossible. The time, effort and

expense involved turned out to be so great that the

engineers said afterwards they would have never attempted

the project had they known its difficulty in advance.

But try they did. And once they got into the project,

they were determined not to fail.

|

|

|

STAGE ONE -

THE BIG DITCH

|

In addition to its thick

jungle, Panama is extremely rugged. Panama has no giant

mountains like the Andes, but has plenty of mini-mountains and very large hills.

The major river of

Panama is known as Rio Chagres (find it on the map). You

can see the Chagres River is much closer to the Pacific Ocean than

the Atlantic.

However, since the Chagres is on the Atlantic side of the

Continental Divide, like the Amazon it is forced to take the longer

route to the Caribbean side.

What the engineers proposed to do

was dig out the 10 mile stretch between the bend in the Chagres at

Gamboa and

connect it to Miraflores Lake on the other side of the

Continental Divide.

There is a mountain

chain that runs through Central America that connects the Rocky

Mountains to the Andes.

Fortunately Panama has

the lowest point on the chain, but the lowest point was still 360 feet above

sea level. Located directly over the Continental Divide, this

was solid rock. Cutting a gap through it wasn't going to be easy.

|

|

|

THE

CULEBRA CUT

In order to connect the Chagres River

to the Pacific Ocean, the engineers would have

to cut through solid rock at a small town known as Culebra

located right next to the Continental Divide.

"Culebra" is Spanish for

'snake'. At first the men speculated this term referred to the

zigzag path of the linked chain of hills. However, once the

rattlesnakes began to slide out of the jungle on a regular basis, there was

no more doubt where the name came from.

The engineers would have

about 10 miles of hills and rocks to deal with before they finished.

Of this ten mile

stretch, fortunately only one

mile required abnormally hard work - the stretch right along the

Continental Divide.

This difficult stretch was nicknamed the

Culebra Cut.

|

|

The entire 50 mile body

of water that crosses Panama is considered the "Panama Canal", but

it was this 10 mile stretch that involved the lion's share of the

work. It was a massive project.

The French had

tried to build a canal in this same spot starting

in 1880. Most of the hard work was done by blacks recruited

from impoverished Eastern Caribbean islands. Some of them

had been slaves as children while most were descendants of the slaves who

had worked the sugar plantations.

Little did those men

realize they were facing a death sentence. Over 22,000 men

would die from malaria and yellow fever. Sad to say, most of them

died in vain. The French got nowhere. In 1890, the

French threw in the towel.

The United States

took over in May 1904. The Americans started work

on a wider, but not so deep a cut. Unlike the French

who believed it was possible to create a canal at sea level, the

Americans had a new plan based on an elevated

lock-based canal.

Unfortunately,

both plans had the same obstacle: a hole had to made in the

mountain range.

|

Yes, man had dug

tunnels through massive mountains before. And yes, man

had widened existing gaps in mountains created by rivers to

build railroads and highways.

However, knocking

a gap through a mountain where there was no previous river

gap to work with was almost unthinkable.

Fortunately,

in the enormous mountain chain stretching from Alaska all

the way to Chile, there was one single point where the mountains

had conveniently turned into low-lying hills - Panama.

The lowest point

in the saddle between Gold Hill on the east and Contractors

Hill on the west was only 333 feet above sea level.

That is where the cut would go.

The depth wasn't

the biggest problem; it was the length. They would

have to cut through ten miles of rock. That was a

daunting task.

The always

cheerful American

press had a name for this 10 mile valley.

They called

it "The Big Ditch".

|

|

|

|

The new plan called for a bottom width of 300 feet. This

required the creation of a valley up to a third of a mile wide at

the top and eight miles long. The gap would have a vertical

distance from the bottom to top 120 feet deep.

That would call

for a lot of digging.

The Americans

had one huge advantage over the French - the French had

already done nearly half the work!

Of the entire 50

mile Panama Canal, the French had already started work on 11

of the miles. The Americans had a big job ahead of

them, but at least they weren't starting from scratch.

A vast amount of new

earthmoving equipment was imported and a comprehensive system of

railways was constructed for the removal of the immense amounts of

earthen and rocky spoil.

Major David du Bose Gaillard, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, was put

in charge. Gaillard brought dedication and quiet, clear-sighted

leadership to this difficult, complex task.

|

|

|

The scale of the work was massive. Hundreds of large steam drills

bored holes into the mountainside. Tons of dynamite were planted

were planted in these holes.

They blasted

the rock out and excavated it using steam shovels which transferred

it to trains. Dozens of trains took

the loose dirt and rock from the shovels to landfill dumps in the

Pacific Ocean

about twelve miles away.

Other trains took an

equally large amount to a project near the Gatun Locks which were

under construction.

In a typical day, 160

trainloads of material were hauled away from the 10-mile long valley

affectionately known as the "Big Ditch".

Actually, there probably

wasn't much affection involved. The work was incredibly

arduous. When it wasn't raining in cascades, it was miserably

hot.

|

|

|

|

At the busiest times,

there was a train going inbound or outbound almost every minute.

This meant the workload on the railroads required some skillful

co-ordination.

Six thousand men worked

in the cut, drilling holes, placing explosives, controlling steam

shovels and running the dirt trains. They also moved and extended

the railroad tracks as the work moved forward.

Twice a day work

stopped for blasting. After the blasting finished, the steam shovels moved in to

take the dirt and rock away and pile it into the trains. More than 600 holes filled with

dynamite were fired daily.

The excavation of the

cut was one of the greatest areas of uncertainty in the creation of

the canal. It could be dangerous. There were many unpredicted landslides caused by

destabilizing the pressure that had once compressed the loose dirt and rock on

both sides of the cut.

There were many minor

slides such as the rock slide pictured on the left. As

problems go, this was nothing compared to the gigantic mudslides.

|

The first slide

was the worst. Known as the Cucaracha Slide, it

occurred in 1907. The initial crack was first noted on

October 4, 1907. Soon it was followed by the huge slide of

500,000 cubic yards of clay. Months of work was

destroyed overnight

The black and

white picture on the right doesn't lend itself to

understanding the problem very well, but let's try anyway.

One problem is that this picture was taken after some of the

damage had already been repaired.

The white area

on the side of the mountain is where the gigantic mud slide

broke away. The mud oozed and dispersed into the

channel. Those steam shovels had to excavate the slide

and start over.

Another

very destructive slide occurred in nearly the same place in

1912 when the canal was nearly complete.

Seventy-five

acres of dirt near the town of Culebra broke away. It

moved foot by foot into the canal, carrying hotels and club

houses with them down into the valley.

It took nearly half

a year to repair the damage.

|

|

|

|

|

Here are

four

different

views of

the 1912 landslide that

caused

so much consternation.

In the

picture on the left, the steam shovels appear to have

already made some progress clearing the area.

|

|

|

|

|

I added the red arrows to illustrate that you are seeing two

different angles of the same problem.

As you can see, at first the mud slide completely dammed the Canal.

|

|

|

|

|

The first slide in 1907

caused many people to bring up the sore subject again that the

construction of the Panama Canal would be impossible. It was

such an enormous setback that the opponents of the Canal argued long

and hard that now was the time to acknowledge the entire project was sheer

folly and quit.

Gaillard was undeterred.

The big slide was a setback, but not a catastrophe.

He described the slides as "tropical glaciers". A glacier, of

course, is made of slow-moving ice. The Big Ditch slides were

made of mud instead of ice, but were just as disheartening. It

was painful to see so much work undone, but that was the risk they

took. When you loosen the

earth, it has a mind of its own.

The huge mounts of clay

were a tough problem because it was too soft to be excavated by the

steam shovels. Eventually Gaillard's engineers discovered the

clay could be removed by sluicing it with water from a high level.

The slides still

continued to cause minor problems after this, but the trick of

liquefying the clay had turned the corner.

Overall the Panama Canal

took ten years to finish. The delay caused by the various slides was estimated at two and a half years.

Nevertheless, even despite the delays, the work on the Big Ditch was

completed two years ahead of schedule. Much of

the credit was given to Gaillard's steady leadership.

In a sad twist of fate,

Gaillard died from a brain tumor in December 1913. He never

saw the opening of the canal a few months later in 1914.

The Culebra Cut, as it was originally known, was renamed to

the Gaillard Cut in 1915 in his honor. However, from

what I gather, the original name still continues to enjoy great

popularity, especially with those who speak Spanish. So

consider the Gaillard Cut to be its formal name, but the

Culebra Cut seems to be the nickname everyone uses.

Whatever the name, much of the credit deservedly goes to David

Gaillard.

The term "Culebra Cut"

specificially refers the toughest one mile cut at the Continental

Divide. However, over time, the term "Culebra Cut" has come to

also refer to the entire 10-mile valley from Gamboa to the Pedro

Miguel Locks once known as "The Big Ditch".

|

|

|

|

This is

the most dramatic part of the Culebra Cut. Notice the

Pedro Miguel Locks and Lake Miraflores in the background.

That is Panama City way in the back.

This image is so

serene that Cruisers looking up from water level are fooled.

They often by have no idea the amount of work

that went into cutting that gap. To them it just looks like

big hills on either side of the canal.

People exclaim, "Oh, look at

the cute little terraces! Wouldn't that be a pretty spot for a hanging garden?"

|

|

|

|

RIO

CHAGRES

The Chagres is the

Mississippi River of Panama. It is 120 miles long and serves as the main escape

route to the ocean for much of Panama's rainwater.

But which ocean does it go to?

There is an enormous,

unbroken mountain chain in the Americas that starts up in Alaska,

continues through Canada and the US as the Rocky Mountains, on

through Central America, and then down through South America as the

Andes Mountains. It is sometimes called the "Cordillera of the

Americas", 'cordillera' being the Spanish term for "chain of

mountains" (actually that unbroken

chain is now broken for the first time thanks to the Culebra Cut, but you know what I mean).

The Continental Divide

is the name given to the mountainous highpoint that separates the water

systems that drain into

the Pacific Ocean from those river systems that drain into the

Atlantic Ocean (including those that drain into the Gulf of Mexico

and the Caribbean Sea).

For example, in the

United States, the majority of rivers head east due to the placement

of the Rockies in the west. But not all Rocky Mountain streams

head to the Mississippi River. The major exception is the

Colorado River. Located on the western side of the Continental

Divide, the Colorado River heads southwest towards the Pacific,

carving out the Grand Canyon along the way. Obviously some waters head

east while other waters head west. That's why it is called

"The Divide".

So what about the Rio

Chagres? Where does its water head... Pacific or Atlantic?

That is actually a very clever trivia question. Thanks to the

Culebra Cut, Rio Chagres is the only river in the world that empties

into two oceans.

But it wasn't always

that way.

The Chagres is on the eastern side of the Continental Divide, so its

original ocean of choice was the Atlantic.

The Chagres River is one

of the moodiest streams in the world. One day

it flows along as a peaceful, lazy little tropical river barely over

two feet deep in some places. It moves sleepily on its journey to the sea.

But watch out when it

rains! After

rainfall, the Chagres becomes a wild, raging torrent with waters 40 feet deep

racing madly toward the sea.

Up in the mountains of

central Panama, the Rio Chagres and its tributaries receive up to

100 to 200 inches of rainfall each year. So is that a lot of rain?

By comparison, the island of Kauai, one of the

wettest spots on earth, gets 460 inches per year while my hometown

of Houston, Texas, gets about 50 inches. So, yes, as you might gather,

even 100 inches is a lot of rain.

When it rains, the

Chagres goes into action instantly. Unlike the gigantic

peaks of the Rockies and the Andes that deposit much of each

rainfall into lakes and ponds, when it rains in Panama, very little

rainwater is contained. Instead the water is delivered almost

instantly to the Chagres. And since practically every other

major Panamanian river connects to the Chagres, back in the old days

this peaceful stream would instantly turn into a raging beast any

time there was a storm.

At these times, the Chagres River

would rush like a raging monster

through narrow riverbeds and canyons with sheer limestone cliffs.

Doubtless many an unsuspecting

Indian in a canoe has been startled by the sudden surge in the river.

However, towards the end

of its journey to the Caribbean, the Chagres would slow down as it flowed into a giant

valley. Before the transformation of Rio Chagres, this valley

was a vast swampland that would periodically flood whenever

there was a significant rain. The valley operated as a

gigantic retention pond. Let me add this swampland was largely responsible for breeding the

massive

swarms of mosquitoes that plague Panama.

Malaria is the curse of

Panama. It is a mosquito-borne infectious disease common to

tropical and subtropical regions, including much of Sub-Saharan

Africa, Asia and the Americas.

Malaria is prevalent in

these regions because of the significant amounts of rainfall and

consistent high temperatures. The last ingredient necessary is

large pools of stagnant water. The Chagres Valley was the

perfect breeding ground. This large, flat marshland had

everything - a warm, consistent temperature, high humidity, along

with abundant stagnant waters providing mosquitoes with the

environment they need for continuous breeding

|

Gold!!

|

The

Rio Chagres has a very colorful past. That color would be the

color of gold.

Or maybe red for all the blood shed fighting over the gold.

It is likely that more gold has passed down the Chagres than any

other river in the world. When the Spanish Conquistadors

looted the Incan Empire in the 1500s, the fastest way to get their

gold from Peru on the Pacific side back to Spain was across Panama

using the Chagres.

The coming of the

Spanish to the Americas was a curse of the highest magnitude for the

people who already lived there. The two words

that best described the Spanish were greed and cruelty. Death,

destruction and disease followed the Spanish wherever they went.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

was a nobody farmer in northern Spain who would lead a rags to riches life.

Captivated by news of Columbus and his discovery of the New World,

Balboa joined an expedition in 1501 that

landed in Panama. There weren't enough men to take on the

hostile natives, so the expedition didn't stay long. The ship headed

back to the Spanish settlement in Hispaniola (today's Dominican

Republic).

In Hispaniola, Balboa became a pig farmer,

but not a very good one. Deep in debt, in 1509 he stowed away on a ship

headed to Panama. He hid inside a barrel with his dog. When

discovered, Balboa nearly thrown overboard by the unpopular

captain Fernández de Enciso. Fortunately

Balboa was a fast talker. He was spared after claiming he knew

everything about their destination.

That was the break he needed.

During the trip, Balboa

became popular with the crew. Balboa had charisma and was

quite the storyteller. He kept the crew fascinated with tales

of what he had seen on his first visit to Panama. Plus

they liked his dog (just kidding). By the time the ship made it to

land, Balboa had somehow managed to become the unspoken leader of

the crewmen.

|

|

|

|

The ship landed in

Colombia at a small Spanish settlement that would someday become

modern day Cartagena. When the ship arrived, the men

discovered the settlement was virtually leaderless. A soldier named Pizarro

with no rank was in charge because the captain had been

wounded by a poison arrow and had returned to Hispaniola. The

natives were busy subjecting the few remaining Spanish to relentless

attacks.

Balboa suggested an area

he had been to that was much less dangerous. On Balboa's word,

the Spanish got

in the ship and sailed 180 miles to a place called Darien.

This location was just a few miles from today's Panama/Colombia

border.

At Darien, it was good

new/bad news. As it turned out, the natives were just as

hostile as they had been at the other place. The moment they

landed, the Spanish had to fight for their lives. The moment

they put to shore, they

encountered a force of 500 villagers armed and ready for battle.

Badly outnumbered, the Spanish won a fluke victory when the leader

panicked and headed for the jungle. His men gave up and ran

after him.

To their amazement, the Spanish discovered the villagers had left

behind a vast treasure trove of golden ornaments. The world

would never be the same.

The victory led to the founding of Santa María la Antigua del

Darién on the spot of their landing. As it turned out, Balboa had been right. Other

than that single tribe, this was indeed a relatively calm region.

The Spanish were finally safe. Balboa's successful gamble

earned him respect among his companions.

Meanwhile, Fernández de Enciso, the

much-disliked Captain, made a serious

mistake. He kept confiscating the gold trinkets found by the

men. The men grew increasingly hostile towards the Captain whom

they considered a greedy despot.

|

|

Balboa took advantage of the situation.

Acting as the spokesman for the disgruntled settlers, while Fernández de Enciso

was away, Balboa took the

position of alcalde mayor for himself. Upon his return, Fernández de Enciso

did not try to get the position back when he saw the men had turned

against him. Instead he left for Hispaniola and would spend the rest of

his life trying to get Balboa arrested.

His nemesis gone, Balboa settled in.

He made sure his men were safe by defeating various tribes and befriending others.

He made sure to explore the nearby rivers, mountains, and the sickly

swamps. The men discovered the thick jungle made

further exploration both difficult and dangerous, so they never went very

far. The existence of the nearby Pacific Ocean 50 miles away remained a secret.

Balboa succeeded in

planting corn, received fresh supplies from Hispaniola,

and got his men used to life as explorers in the new territories. He

was always searching for gold and slaves and ways to enlarge his

territory. Balboa managed to collect a great deal of gold, much of

it from the ornaments worn by the native women. He obtained the rest

by violence.

Balboa, the former

stowaway, faced constant threats from visiting Spanish officials

who upon discovery of his lack of "official" authority

would threaten to

have him removed. Balboa showed an uncanny political savvy for

survival that allowed him one narrow escape after another.

Like the Old West, Balboa took advantage of his remote

location from Spanish Law.

Even his own men became

a problem. Balboa was able to quell revolts among those of his

men who challenged this authority.

As for the natives, Balboa

could be ruthless, but was basically a huge cut above the other

notable

Spanish invaders of the day. Although he had the ever-present threat of force

at his disposal, Balboa preferred to use

diplomacy and negotiation to earn respect among

the natives. Plus they feared standing up to him. An uneasy peace settled over the area.

|

|

After three years of

settling in at Santa Maria,

Balboa felt secure enough to begin a more extensive exploration of

the surrounding areas. However, he stayed pretty close to the

Caribbean shoreline, moving along the coast but not inland. Any trips deep into the interior

of Panama were deemed too dangerous.

At the end of 1512,

Balboa arrived in a region dominated by the native leader Careta,

whom he easily defeated and then befriended. Careta was baptized and

became one of Balboa's chief allies; he ensured the survival of the

settlers by promising to supply the Spaniards with food.

Balboa then proceeded on

his journey, arriving in the lands of Careta's neighbor and rival,

native leader Ponca. Ponca immediately fled to the mountains with his people,

leaving his village open to the plundering of the Spaniards and Careta's men.

Balboa had learned a secret - he could use the natives to help

conquer other natives. While Balboa was busy using the sword

to do God's work in the New World, the Spanish Inquisition was in

full swing back home. Considering how religious Spain was, it was

truly a barbaric empire.

Days later, the

expedition arrived in the lands of the leader Comagre. This

tribe of natives were reportedly dangerous, but Balboa was received

peacefully. Preceded by his reputation, he didn't even have to

fight. Balboa was even invited to a feast in his honor; Comagre, like Careta, was then baptized.

Spreading Catholicism was lucrative business.

The Spanish, as always,

were greedy for more gold. One day a squabble broke out

between the Spaniards and the Indians. The Spaniards were

unsatisfied by the meager amounts of gold they were being allotted.

Comagre's eldest son, Panquiaco, was angered by the Spaniards' avarice.

He

knocked over the scales used to measure gold and exclaimed, "If you

are so hungry for gold that you leave your lands to cause strife in

those of others, I shall show you a province where you can quell

this hunger."

Panquiaco told them of a

kingdom to the south where people were so rich that they ate from

plates and

drank from goblets made of gold. He added with a smile

that the conquerors would need at least a thousand men to defeat the

tribes living inland and those on the coast of "the other sea."

The other sea?

What other sea?

The promise of a new

kingdom rich in gold was a major lure, but Balboa's curiosity about

the sea was an even larger motivation.

Balboa returned to Santa

María at the beginning of 1513 to get more men from Hispaniola

for a major expedition. It was then that he learned that his old

enemy Fernández de Enciso had told the colonial authorities what had

happened at Santa María. Balboa was considered an outlaw.

After seeing that there would be no assistance from Hispaniola,

Balboa sent Enrique de Colmenares directly to Spain to look for

help.

Colmenares returned with two pieces of bad news. Enciso's case

was widely known in the Spanish court. Angered by Enciso's

allegations, the King was in no mood to send more men.

Therefore, Balboa had no choice but to carry out his expedition with

the few men that he had on hand in Santa María. This would be

a risky adventure.

Balboa had been told he

needed a thousand men, but he only had less than two hundred men.

However he did have several vicious bloodhounds. Yes, even the

Spanish dogs were mean. The natives had always been especially

terrified of the dogs, so he would take them along.

Balboa was undeterred by

the danger. He had waited long enough. So with just a few men

and a lot of guts, Balboa entered the interior of Panama.

Slowly but surely

Balboa fought his way through the thick jungle in search of "the

other sea". The expedition's rate of advance through the

jungle was at times only a mile a day. The rivers were swollen

during the rainy season. Numerous bridges had to be improvised from

tree trunks. Even in the sweltering jungle, the Spaniards wore

helmets and breastplates of polished steel, thick leather breeches,

woolen stockings, and thigh boots.

Heatstroke, hostile Indians, and disease began to thin their

numbers. Balboa was down to one-third of his men.

|

On September 25, Balboa

reached a small hill along the Continental Divide. The guides

whispered to Balboa that he could see the Great Ocean from the

summit. Balboa told his men to stay and set off alone.

From the high point Balboa viewed the Pacific

Ocean for the first time. Only a mere 12 miles separated

Balboa from the gigantic body of water. Balboa was the first

European to ever see this amazing ocean from the Americas. At

the top, he turned one way and then the other; he could see both

oceans quite clearly.

It was now 1513.

This had to be an awe-inspiring moment for the group. However

life is full of irony. Who would ever imagine that Balboa's

greatest moment would also mark the beginning of his end?

Among the men in Balboa's group peering down upon the great ocean

was none other than Francisco Pizarro, the man who would

conquer the vast Incan Empire 20 years later. However, before his days of

glory in Peru, Pizarro would first play a hand in Balboa's death.

|

|

|

After his discovery of the Pacific Ocean, Balboa returned to

Santa Maria. From there, he sent word to the King

Ferdinand of

Spain of his amazing discovery as well as a treasure chest

full

of gold as a present to the King. Since Balboa's

discovery was almost as impressive as that of Columbus, ordinarily you

would expect the King to be pleased. Not this time.

The gold

definitely got King Ferdinand's attention, but there also

these troubling reports made by the political enemies Balboa

had incurred during his illegal rise to power in Panama.

|

King Ferdinand

dispatched Pedrarias,

a Spanish nobleman, to

take charge in this lucrative new world.

Pedrarias was a tough guy known for his cruelty.

He landed in Panama in July 1514

along with 17 ships and 1,500 soldiers. Faced

with that kind of muscle, Balboa knew the gig was up.

His reward for discovery the Pacific was to lose his

job.

Balboa was no longer governor and mayor.

Balboa

was imprisoned as well. Fortunately, his

prestige and his fast-talking ability got him free,

but he was kept on a short leash.

Pedrarias was no

fool. Balboa was the local hero and had the loyalty of many. Pedrarias

kept a close eye on Balboa at all times. He knew as long as Balboa was around,

his own position would always be in danger in this remote

location.

Balboa

could tell he was

a marked man. For the next five years, Balboa did

everything he could to ingratiate himself with the

thug. Balboa went to the trouble of marrying one of Pedrarias' daughters, but

even that couldn't save him from

his ruthless father-in-law. Pedrarias refused to trust

Balboa's motives. He knew as long as the

popular Balboa

was around, there would always be the threat

of an insurrection.

In 1519, Pedrarias ordered Pizarro to intercept Balboa on

the way back from a mission. He gave Pizarro the

authority to execute Balboa on some trumped up charges.

It was basically a Mafia hit. There was no evidence

that Balboa was planning any coup; Pedrarias had simply

grown tired of keeping the threat around.

Balboa

lost his head. His

amazing run of good luck had run out.

|

|

|

The Spanish

Empire

The first man to the New

World gets the gold.

Thanks to explorers such

as Columbus (the Americas) and Magellan (Philippines) as well as

conquistadors such as Balboa, conqueror of Panama, Cortes, conqueror

of Mexico, and Pizarro, conqueror of Peru, Spain began to acquire

incalculable amounts of wealth.

Spain would exploit the

riches of South America, Central America, and the Caribbean for the

next four centuries.

This zenith of Spanish

influence would spread Spanish blood, culture, and language to far

regions across the planet. These were the days of the mighty

Spanish Empire.

|

|

Now it is true that the Spanish were powerful and

aggressive, but I also think they enjoyed the greatest

run of dumb luck in history. It started with Columbus.

Columbus had no idea what he was doing, completely

miscalculated the circumference of the Earth, but stumbled onto

the Americas nonetheless. That was sheer dumb luck.

He was so confused he thought he was in India of all places.

And now we celebrate Columbus Day once a year. Go

figure.

Even Balboa was

lucky. When he persuaded Fernández de Enciso to move

his men to Darien, 50 Spanish faced 500 armed natives.

But somehow the Spanish prevailed because the indigenous

people failed to realize that 50 guns shooting one bullet at

a time were not sufficient to stop 500 determined warriors.

Hernan Cortés

conquered Emperor Moctezuma and the vast Aztec empire aided

by the good fortune of being mistaken for the return of an

Aztec deity.

However, when we

speak of dumb luck, the man who takes the cake has to

Francisco Pizarro. Pizarro had the luck of taking on

the dumbest ruler in history.

Like Balboa,

Pizarro was another commoner with an uncommon amount of

ambition. Pizarro had nothing against Balboa.

Pizarro had served under Balboa in Panama for 18 years.

However, when asked by Pedrarias to take out Balboa, Pizarro was easily bought for the right price.

As reward for his part in the treachery, Pizarro was made

major of Panama City.

While at this post, Pizarro

heard rumors of vast wealth at some place called Peru 1,000

miles away. Pizarro was intrigued. Pizarro

immediately began a series of probes which seemed to bear

out the rumors.

Pizarro spent the next ten years in

various maneuvers trying to figure out what to do. He

was underfunded, undermanned, and had become

something of a renegade himself. There was a "wanted"

poster out on him. But his unrelenting ambition kept

him going.

In 1532, Pizarro

was finally close to the prize. He took on Atahualpa, the

ruler of the Incan Empire. From what I read,

Atahualpa might possibly be the dumbest ruler in history.

He paid zero attention to this new threat.

Although Atahualpa was in the middle of a civil war when

Pizarro showed up, he wasn't at all worried. And why should

he? There were fewer than 200 Spanish as opposed to

his 80,000 soldiers. That complacency was the mistake

that caused his death and doomed the Incan empire.

And just how did that happen? Basically Pizarro caught

the guy napping, but the sequence of events was so

far-fetched that I have trouble believing any of it.

The whole tale is non-stop Pizarro Bizarro.

It is also much too complicated to do in 3 million words or

less. Therefore I suggest for now we stick to our Panama

story and save that tall tale for the time we take a cruise

trip to Machu Picchu.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Suffice it

to say, after Pizarro miraculously succeeded in overthrowing

Atahualpa, pretty soon a vast amount of gold was suddenly

headed in the direction of Panama.

The Chagres

River is only 12 miles from the Pacific. Thanks to

Pizarro's amazing luck, overnight the Chagres became the

most important river in the world.

First the Incan

gold was shipped 1,000 miles from Peru to Panama City on

Panama's Pacific coast. From there it was transported

by mules

15 miles across the Continental Divide using El Camino Real

- the King's Highway.

At that point,

the gold was then loaded onto boats which used the

Rio Chagres to cover the remaining 40 miles to reach the

Caribbean side.

|

|

|

|

The

California Gold Rush

Strangely enough, 300

years later after the Spanish Dias de Oro, history would be repeated. The 1849 California

Gold Rush utilized the Chagres River in much the same way as Pizarro

had.

The spark that

created the bonfire were some extremely exaggerated press

reports about gold discovered in California. A

frenzied migration was triggered by the illusion that every

gold digger would automatically become a millionaire if he

could just get there in time. According to some

newspaper reports, gold was literally lying on the ground.

All a man had to do was bend down and pick it up.

There was a story circulating about a cleaning woman who

swept gold dust worth 500 dollars from a saloon floor within

a day.

Tales like these

spurred people's imagination and provided them with false

expectations. They needed to get there as fast as

possible before all that wonderful gold was gone. The fastest way

to get from New

York City to San Francisco was by boat - sail to Panama, cross the

Isthmus, then take another boat to California. Likewise, the

fastest way to transport gold back to the East Coast was

through Panama using the Chagres River.

|

|

There are some pretty

wild stories involving Panama from that era.

In the

early days of the Gold Rush, when word of the easy

pickings reached the East Coast, thousands of men in

the East dreamed of striking it rich. And what

was the fastest way to San Jose? Through

Panama!

|

|

So they

hopped aboard ships that dropped them off in Colon

on the Caribbean side. Then they took small

boats via the Chagres River all the way to the

Continental Divide. Then they walked a mule

path the final ten miles to Panama City to await the

next ship to San Francisco.

Except

there was one problem - There were no ships

waiting for them in Panama City.

What had

happened was that many crewmen had deserted their

jobs aboard ships the instant they reached San Francisco. They headed straight for

Sutter's Mill and other rumored

gold areas. No one in San Francisco wanted to work the ships;

like everyone else they wanted to strike it rich.

As a

result, one ship after another entered the harbor,

but didn't leave. At one point, the San

Francisco harbor was 7 ships deep in abandoned ships.

Until the captain could find someone to work for

him, they would sit there in the water like ghost

ships.

|

Meanwhile, thousands of

impatient would-be miners were stuck in

Panama City waiting for the next ship to come pick them up.

Each day when no ship showed up, these men grew increasingly

desperate. If they could just get there in time, they

would be rich! Going nowhere was driving them crazy.

Idle hands are

the Devil's workshop and Panama City was a boomtown without

a boom. Hundreds of men hung around the ticket

agencies waiting for news of steamers arriving. Still

others followed the agents around town just so no covert

actions would go unnoticed. They soon realized this

tactic didn't do a bit of good.

Left with

nothing else to do, the men spent their time with booze,

brawls, and brothels. There was gambling, stealing,

and constant arguing. During the day men roamed the

streets, drinking and frequenting the many gambling

establishments. Although the national pastime seemed

to be cockfighting, the gambling houses had roulette wheels,

faro banks, and monte boards to amuse everyone.

In the

early days of the Gold Rush, there was practically

no police force in Panama City. This was a

somewhat uncivilized area in the first place, so the

citizens were ill-equipped to deal with this sudden

onslaught of impatient men trapped in their city.

Panama

City was quickly overwhelmed by this endless crush

of men. These were rough men to begin with and

now they were frustrated. Some of them turned

into thugs and took their anger out on the local

citizens. They treated the locals badly, hurting the

women and beating the men in broad daylight for no

reason. For a while there, the town was in a state

of near-constant mayhem.

One day

panic broke out. A ship came in with room for

about 1,000 passengers... but there were 3,000 men

waiting. There were insufficient controls

established for who would get those spots. The

bullies shoved people out of their way in their rush

to get to the front. The people they were

pushing shoved back.

Suddenly

there was fighting everywhere - gunfights,

fistfights, and knife fights. Miners were

fighting miners. Miners were fighting

Panamanians. The riot spread through the city.

Panama City was beset by dog eat dog lawlessness.

During the riot, many stores were looted for

provisions and supplies by men whose money and

patience had run out. It was an ugly mess that

took quite a while to restore order.

The

overcrowding problem was eventually solved in a

bizarre way. Stuck in Panama for months at a

time, many of the men got sick with fever, malaria

and cholera.

|

|

|

|

Just as the police force

was unable to cope with the roughhousing, the hospitals were not

much help either. Back in those days, there was no cure for

yellow fever. Whiskey was the main treatment. An adult

had about a 50-50 chance of survival.

Many of the would-be

miners died in Panama far from their homes. They were alone

and had no one to comfort them. In great pain and full of

fear, they died miserable deaths. Their Gold Fever had turned

into Yellow Fever.

Death by Panama Fever.

What an awful way to die. On the other hand, considering how

poorly many of these men had acted, some might say they got what

they deserved.

Meanwhile, up in the

California gold fields, many of the get-rich-quick types had

discovered it wasn't going to be as easy as they had believed,

Full of disappointment, they returned to San Francisco. Men began to

hire on ships to get them moving again. Panama City finally

returned to normalcy.

The heyday of the

Chagres River ended 6 years later. It was put out of the gold business by two railroads. First the

Old Panama

Railroad was completed in 1855. Then the USA completed its

first transcontinental railroad in 1869. From that point on, the

trains carried the gold.

Its glory days seemingly

over, the Rio Chagres returned to its role as chief waterway of

Panama. At that point, the

Chagres River should have disappeared into history as nothing more

than a footnote, but in 1880 it made a comeback when the French

began their attempt to build a canal.

Although the French

effort would fail, the Americans found a way to finally harness the

mighty Chagres River. They used the Chagres River to create the only waterway in

the entire world to directly link two great oceans.

The

construction of the Panama Canal at the turn of

the century had a real touch of irony. The same waters that

had once carried so much gold had suddenly become more valuable to

the world than gold itself.

|

|

Trivia Question: After the French effort to build

the canal failed, the United States immediately showed

interest in a canal project of its own. There were two

major routes under consideration, one through Panama and

other Nicaragua. In 1897 and 1899 two fact finding

commissions appointed by the United States Congress

recommended the Panama route. True or False?

(answer in a moment)

|

|

STAGE TWO -

THE BIG

BATHTUB

|

This picture makes me dizzy. Do you have any idea what you are

looking at?

This picture is an

overhead view of the Gatun Locks (upper right corner) and the Rio

Chagres dam (center).

The earth and rubble

eventually removed from the Big Ditch would be enough to bury

Manhattan to a depth of 12 feet.

So where do you suppose

all that dirt and rock went to? The nearby Pacific Ocean?

Well, yes, some of it did. There was an island about three

miles off the coast of Panama. Using the debris to fill in the

gap, the island was connected to the mainland. The area was turned into a

thin peninsula known as the Naos Island

Breakwater.

However, they had

another very important use for the rock spoil. Every day for several years 100

trainloads of waste rock and dirt were transported 30 miles from the

Culebra Cut and deposited

into the Rio Chagres valley.

What do you suppose they

were doing?

|

|

They were building a dam at a town called

"Gatun". Gatun was a small fishing village about six

miles inland from the Caribbean Sea that sat along the banks

of the Rio Chagres.

When people visit the Canal for the first

time, almost everybody has the same mental picture of

the Canal before their first visit -- a long narrow body of

water, twisting and turning through the jungles of Panama.

Unless they study up in advance, they

are very surprised to learn that

almost half of the Canal is just a

lake... and a very big lake

indeed!

It is time to learn about the

"The Big

Bathtub". The

man-made Gatun Lake is the amazing trick

the engineers used to finally tame the

churning waters of the

unpredictable Chagres River.

|

|

If you remember,

the French plan was to build a sea level canal, but the

American plan was raise the waters. But what on

earth were they talking about? They were planning

to create an artificial lake.

In the picture, you

can see the massive dam they put in front of the Rio

Chagres. Once the waters had nowhere to go, the entire Chagres Valley

filled up like a giant bathtub. The Chagres

River had been about 42 feet above sea level at its Gamboa bend.

Now, thanks to the dam, the river elevation reached 85 feet. They had

indeed raised the water.

The Chagres

Valley was gone never to be seen again. In its place

came Lake Gatun, the largest man-made lake in the world at

the time.

|

|

|

BEFORE |

AND AFTER |

|

Have you

ever seen a more amazing transformation?

They didn't

bother "lowering" the Rio Chagres by digging it out. Instead

they "raised" it. As you can see, by damming the

Chagres, a huge valley was transformed into an immense lake.

The new

Lake Gatun was 85 feet above sea level. That red line in the

water marks the path of the original Rio Chagres.

|

|

The Beauty Contest

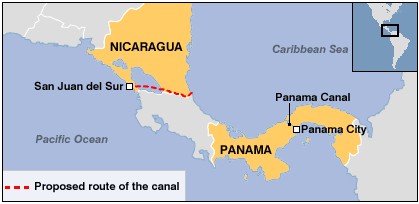

Before the

Panama Canal was built, it first had to win a beauty contest

with another proposed route in Nicaragua.

Trivia

Question: After the French effort to build the

canal failed, the United States immediately showed interest

in a canal project of its own. There were two major

routes under consideration, one through Panama and other

Nicaragua. In 1897 and 1899 two fact finding commissions

appointed by the United States Congress recommended the

Panama route. True or False?

So

what did you decide, Panama or Nicaragua? In fact,

both commissions recommended the route in Nicaragua as

superior.

|

|

So what made

Nicaragua so attractive? Nicaragua had one compelling advantage.

It had a massive lake in the middle of the country.

The lake

was 107 feet above sea level, so no digging would be

necessary. Since the lake drained to the Caribbean Sea

via the San Juan River, all they had to do was dredge out

the river a bit.

To the naked eye, 90% of the route

was easy pickings. Only the hills on the Pacific side near San Juan

del Sur would present any sort of problem. But since

its lowest point was 184 feet above sea level, even this

beat Panama's Culebra Pass at 336 feet.

On the other

hand, Panama was the shorter route, but it had no lake to

use for the "lake and lock" system typically used for canals

through uneven terrain. Furthermore, its major river,

the Chagres, was difficult to control while the San Juan

River of Nicaragua was not a problem. Nicaragua had

won the beauty contest fair and square.

|

When

Teddy Roosevelt decided it was time to build a canal

in 1901, both options were put on the table.

Nicaragua had the inside track.

The

French were absolutely panic-stricken. They

had all this money sunk into their failed Panama

project. The only possible way to recoup some

of their losses would be to persuade the Americans

to change their mind about Nicaragua. France's

New Panama Canal Company began a strong lobbying

effort to influence the final verdict. The

French offered to sell its equipment and license in

Panama at a major discount.

This

offer put Panama back in the running. Yes, the

Nicaragua route was superior, but the fact that the

French had already dug out 11 of the 50 miles needed

to finish the project definitely helped to balance

the scales. The French lobbyists persuaded

Congress to pass an amendment to a bill that would

allow the President to acquire the French company's

Panama property and concessions at a cost not to

exceed $40,000,000 and to acquire from Colombia

perpetual control of a canal zone.

If the

title and an agreement with Colombia could not be

reached in a reasonable period of time, the

President was authorized to proceed with a canal at

Nicaragua.

However,

all this was contingent on a vote. Congress

had the final say-so. Even with the French

concessions, some

old southern senator had it stuck in his brain that the only

place for a canal was Nicaragua. He

wasn’t an engineer but he did have a big

mouth in the senate. He used his influence to hold up

the process.

The debate went on and on in

Congress. There were rumors that

money was secretly changing hands during the debate.

This was going to be a close

and hotly-contested vote.

|

|

|

Then one day, a major

Nicaraguan volcano erupted

and there were

earthquakes. This

didn't help

Nicaragua's chances at all.

Volcanoes were Nicaragua's Achilles heel. This

country the size of New York had a very volatile

geology.

Known as

the Land of Lakes and Volcanoes, Nicaragua's

detractors said the geology was simply too dangerous

to risk this expensive project on. What if a

volcano erupted and seriously damaged the canal?

What if it became an ongoing problem?

Good

point. Now it was Nicaragua's turn to panic.

|

Frantic

Nicaraguan officials sent a

telegram to the US denying the eruption and earthquakes

had taken place. The southern

senator claimed his foes had made up the natural disasters. The truth was

that they didn’t. However, news traveled slowly

in those days, so the recent eruption remained more rumor

than fact.

Someone noticed

that a

popular Nicaraguan postage stamp was

engraved with a fuming volcano. One of the proponents of building

the

canal in Panama cleverly sent every

voting senator

a letter using that stamp

for postage.

When the vote

was taken, it was close, but Panama finally won by 4

votes. An

unconfirmed rumor hinted the blustering senator blew his top.

|

Chagres Valley Becomes Lake Gatun

|

The US engineers

breathed a huge sigh of relief when Panama was declared the

winner. By this time, all the US engineers

had decided Panama was a better choice.

For one thing, they

liked the fact that they could build on the work of the French.

Besides, Panama had a railway next to the canal site.

Nicaragua didn’t.

Furthermore, the French

had already cleared a lot of the jungle.

The clearing made it

easy to survey and measure distances. Nicaragua was still a jungle and

impossible to survey. There were simply too many unknowns

there.

On the

other hand, Panama still had its drawbacks. The

greatest difficulty of

the Panama route was how to

control the often-powerful

Chagres River and its many

tributaries. The

Chagres River rose in the

San Blas Mountains and drained a

huge basin of 1,320 square miles,

nearly half of Panama.

Controlling the Chagres was like telling the

Mississippi what to do.

The

upper section of the Chagres was a real monster

whenever it rained. However the Chagres slowed

considerably when it reached the vast

low-lying Chagres valley.

The general elevation of the valley

was

barely above sea-level.

That meant the Chagres River wasn't nearly deep enough to allow

a modern ship to cross it.

The only

solution would be to dredge a deep channel into the

Rio Chagres. But maybe not. Someone had an idea. Why not turn the

entire valley into a deep lake? Brilliant! No

digging necessary!

One of the major

factors in Nicaragua's favor had been the presence of its

massive Lake Nicaragua right in the middle of the proposed

canal route.

Yes, Panama had no lake comparable to Lake

Nicaragua, but the engineers had figured out how to

solve three headaches with just one stone. They could

tame the Chagres River and create a massive lake using the

same solution - put a dam across the Chagres in just the

right place. Plus now they had a good spot to deposit

all that excess rock and dirt from Culebra.

|

|

|

|

When the

engineers had originally studied the topography of Panama, they spotted

an unusual depression in the land near the Caribbean.

What could have created such an immense low spot in this

mountainous country? The features of the valley were

such that it didn't look like the Chagres River had created

it. The area was much too wide and "unsymmetrical" for

that. There was none of the usual tapering of hills

alongside the river.

That led to speculation that

the area may have been the remnants of a

volcanic crater. Many mountain lakes have formed in the cones

of dormant volcanoes.

However the

depression lacked many of the features commonly associated

with volcano craters. For one thing, volcanic craters

are elevated. This was right at sea level.

That led to

another theory that the vast Chagres Valley might be an impact crater.

In other words, a falling meteor might have created the giant

depression.

Whatever the reason, it was apparent to everyone that the terrain was

unusually well-suited to creating a reservoir. A line of hills on

all sides of the valley formed a natural

bowl.

Those hills helped make Chagres Valley a natural drainage basin. Parts of the valley

would flood whenever there was a heavy rainfall. This is what

led to marshy conditions that made this area a giant swampland.

|

|

But why was there no lake? Because there

was one noticeable opening in the ring of hills. The Rio Chagres was nearly

a mile wide at the gap where it left the valley.

No matter how

hard it rained, the Chagres would drain the waters

through that gap. The engineers noticed that the tall hills bordering the valley of the Chagres

meant there was no possible escape for any water if that gap could

be plugged.

If they

could just find a way to close that huge gap, the geography of the area

was ideal for the creation of a large lake.

|

Unfortunately a mile-wide gap is an unusually broad span for

a dam.

If they wanted to make an

earthen dam, they would need a huge amount of dirt.

Well, we know the answer to that. Thanks to the Big

Ditch, the Big Bathtub had all the dirt it needed.

So Lake Gatun was created by a

gigantic earthen dam

designed to bridge that mile-wide gap

between the two hills.

This dam project took all that dirt and rock from the

Culebra Cut and put it to good use.

Let's see if we

can get an idea of the magnitude.

In the picture,

Lake Gatun is to the right, Rio Chagres is flowing out to

sea on the left. That entire grassy

area was added to the sides of both hills to help create the

dam. Since Gatun Dam is slightly higher than 100 feet

tall, don't forget that grassy area is not only a mile and a

half long, it is also nearly 100 feet

high. That's a lot of dirt.

Compared to other dams,

a height of 100

feet is no big deal. For example, our own Hoover

Dam has a height of 726 feet because it was built to seal a deep

canyon.

|

|

|

However, Hoover

Dam's width

is only 1,200 feet. By

comparison, Gatun Dam is 8,400 feet

wide and juts

out a half mile into the lake

at the base.

By all

standards, the completion of the immense Gatun Dam was a major project

equally as important as the excavation of the Culebra Cut.

As predicted, creating Lake Gatun

solved many problems. The raging Rio Chagres would never cause

another flood. Take a quick look at the size of Lake Gatun. Anytime it rained, the water level of the lake

would simply rise a foot or so. Big deal. Any excess would spill over

Gatun Dam and run out to sea. The mood swings of

the temperamental Rio Chagres were finally tamed.

Thanks

to the creation of Lake Gatun, the Chagres River would not have to

be dug out. The United States

had just saved

a decade of more digging that a sea-level canal would have required.

This was an immense relief since the bottom of the

Chagres was hard rock, not soft sand like the Suez Canal. After all the problems with the Big Ditch,

no one was in much of a mood to do any more digging.

|

Once the

dam was finished, the waters of the Chagres were suddenly trapped

by the giant man-made mountain.

The Chagres slowly began to fill the valley

using the waters of its 1,320-mile

watershed.

Lake Gatun was created gradually over a period

between 1908 and 1911.

When

the waters finally touched the top of the dam,

Lake Gatun had become the largest artificial lake in

existence at 164 square miles with a shore

line of 1,100 miles.

The most

important statistic about

Gatun Lake is that it now rested 85

feet above the Atlantic Ocean.

That impressive

depth was more than necessary to get the job done. A

cruise ship, for example, required 25 to 28 feet of water

depth.

85 feet was more than enough. Lake Gatun was

perfect.

So what is the largest man-made lake in the world

today? I knew you were going to ask this question, so

I looked it up.

|

|

|

|

Unfortunately, recent projects

have completely knocked Lake Gatun off the Top Ten list. Some dam

going up in China on the Yangtze is supposed to break all the

records. However, at the moment Lake Volta in Ghana has the record with

3,275 square miles.

That makes it about 20 times larger than Lake Gatun.

Oh well. There's always a bigger fish in the sea and

I suppose a larger

artificial lake as well. Still, Lake Gatun doesn't have to

hold its head in shame; it is just as big as some of the most famous

lakes in the world. For example, it approximates

Switzerland's Lake Geneva in size.

The Chagres Valley was

not exactly one big level area, but rather many separate valleys

with differing elevations. During the flooding process, it took several years for the rain to fill the

convoluted valleys.

|

|

Whenever one valley filled, the trapped Chagres

water would start flooding the next lowest one.

Before

it was flooded, the Chagres Valley was a low-lying

area that drained slowly whenever it rained. This

vast swampland was perfect for two things - breeding

cattle and breeding mosquitoes.

|

|

The valley also had places that were heavily

forested.

In the process of

flooding the giant valley, the waters killed off all the low-lying forest. Today

nearly a century later ancient mahogany tree trunks still tower

over the water in certain places.

In addition,

submerged stumps form hidden hazards for any small vessels that wander off

the marked channels.

|

Trees weren't the only

things buried by the water. Raising the waters 85

feet meant that all sorts of things were covered up. For

example, several sections of the Old

Panama Railroad went underwater (a new one was built as part of the

Canal construction).

The town of Gatun went under as well.

So

did many farms and native villages. Fortunately Panama was not a

crowded country back in 1900. Everyone found new

property to start over without much trouble.

Slowly but surely, the

rising waters turned hills into islands.

100 foot hills became 15 foot islands. Some of Gatun's

new islands were large while others just barely poked their

nose above water. The cruise ship will pass several

of these forest-covered islands as

it crosses Lake Gatun.

Islas Brujas and Islas

Tigres are small islands which together hold a primate refuge.

Unfortunately, visitors aren't allowed.

Too many wild apes.

|

|

|

Since the flooding

process didn't happen overnight, the flood posed no danger for animals.

When the waters grew high enough to pose a threat, the animals

simply headed towards the nearest hill.

Not surprisingly, the

most popular hill was the widest and tallest one, Barro Colorado.

Once the animals made a new habitat there, they became permanently

trapped as the waters continued

to rise. Not that the animals minded. The island was

soon surrounded by so much water it became a sanctuary for them -

no predators could reach the place. The small animals

were safe.

Only the larger

animals like

jaguars disappeared from Barro Colorado

after the lake was flooded in 1914.

Because Barro Colorado was so isolated in the middle of the

giant lake, the island became a perfect spot for a game

preserve and a place to study nature undisturbed by the

influence of man.

That

is how Barro Colorado became

one of the world's

first biological reserves.

|

|

The Smithsonian Tropical Research

Institute has a permanent center on Barro Colorado island

dedicated to studying rainforest ecosystems.

Because the island's

diverse ecosystem has been little altered by humans, Barro

Colorado has been studied for over eighty years within a great

variety of biological disciplines.

Many scientific studies have been conducted

to document the changes in the species composition of the island.

|

|

The lake itself is home to crocodiles

- swim at your own risk - as well as manatees.

The favorite fish is peacock bass, a species introduced from

South America that is popular with

fishermen. Fishing charters for bass, snook, and tarpon

can be scheduled most easily in the town of Gamboa

located at the fork where the Rio Chagres

merges with the Panama Canal.

Wouldn't it be fun if

the cruise ship would stop in the middle of Lake Gatun and let its passengers

spend the afternoon fishing for their dinner? No fish, no

dinner. Hand me a pole!

|

|