|

THE

WIZARD OF OZ

Rick Archer's Note: The following story is

important to me for several reasons.

Recently a

neighbor mentioned he had retired. After I

congratulated him, he said he needed to send me his non-work

email address so he could continue receiving the SSQQ

Newsletters. It turns out he likes some of the jokes

and stories.

Flattered by his

interest, I asked if my stories helped him believe in Fate.

He answered with

a smile, "One thing I'm certain of is that you believe in

it."

Which is true.

I am a firm believer in Fate. Which is why I like this

story. It has Fate written all over it. It is

the story of how a talented and very proud man got taken to

the cleaners twice in a row at the peak of his career.

A street hustler conned him to the tune of a half million

dollars while some Aussie guy named Rupert Murdoch stole his

life's work right out from under his nose. Talk about

a double dose of humiliation. He lost his job and he

lost his reputation.

Knocked for a

loop, some people might have thrown in the towel. Not

this guy. He came up with one of the ingenious

comeback plans I have ever heard of. He waved his

magic wand and produced a movie known as Urban Cowboy

out of thin air.

I doubt anyone

else has ever told this man's story. The only reason I

know the tale is because my dance career hitched a ride on

this man's comet. As he soared, so did my career as

Houston's first Country-Western instructor. This is a

very curious tale; I think you will enjoy it. --

Rick Archer

|

|

MAGIC CARPET RIDE

the disco

years

CHAPTER EIGHTY SIX:

THE WIZARD OF OZ

Written by Rick

Archer

|

|

SEPTEMBER

1979. THE YEAR

OF LIVING DANGEROUSLY

THE MYSTERIOUS WIZARD OF OZ

|

|

Rick Archer's Note:

So what exactly

led to my career as a Country-Western dance instructor?

Probably the best place to start is the secret behind Houston's

strange Western Transformation in 1979. The spark that started

this bizarre Transformation was the opening of

Cowboy, the first C&W club to ever attempt to

attract wealthy professionals to a kicker joint.

Starting with Cowboy

in February 1979, over the next six

months two dozen or so Houston-area

Discos had closed only to reopen a month later as a

Western dance hall. As the result of these unexplained changes, at the start of September

only four well-known Discos were still standing...

Annabelle's, elan, Tingles, and Pistachio Club.

This phenomenon

upset me no end. The Death of Houston Disco Clubs was like

Russia burning its crops to stop Napoleon. Without

food to feed his troops, Napoleon had no choice but fold his

tent and head back to France. By comparison, if my students did not have a place to

dance, Disco would starve to death.

Here is what was

weird about Houston's Western Transformation.

Simultaneous to the demise of Disco in Houston thanks to the

Country-Western threat, Disco was hitting its absolute popularity

peak in every other part of America. Indeed,

while Disco was on its death bed here in Houston, it was

gangbusters everywhere else. Houston was the lone exception.

"Why?", I asked. What possible

reason could explain why Disco was facing a premature death

in Houston? I asked around,

but no one had any idea. We figured it had something to do with

John Travolta and this strange movie he was filming, but as

I would later learn,

that was just the tip of the iceberg. Clearly there

was more to this mystery. At the time, my

conclusion was that someone was orchestrating these changes

behind the scenes. In my thoughts, I referred to the

mystery man

as the Wizard of Oz.

|

|

As it turned

out, I was absolutely correct. There was indeed a Wizard of

Oz behind all these changes. Now for the

irony. I never learned who he was until 40 years later.

Why did it take so long? For one thing, although there

were plenty of articles about John Travolta, Gilley's,

and the filming of Urban Cowboy, there were no

articles in the newspaper to explain the Western

Transformation.

Why not?

Because no one particularly cared. Curious, maybe, but

not threatened. Wait, let me change that.

There was one person who cared. Me. I would

venture a guess I was probably the only person in

Houston whose profession was threatened with extinction by

Urban Cowboy. It wasn't like anyone else

was out of a job. The club owners still owned a club

while all the bartenders and waitresses had to do was go out and buy a pair of jeans. Sure, there were other Disco instructors who

were inconvenienced, but they just went back to teaching

Ballroom. And yes, my Disco students were very

irritated, but unlike me, they did not wrap their entire

existence around Disco. If Disco went away, they would

adapt. Not me. Disco was my identity, my

reason to be happy. Why not teach Ballroom? I

hated Ballroom dancing and I hated the music. Why not

teach Western? I hated the music and there was nothing

to teach.

|

|

Given how much I loved to teach dance, my

depression grew worse as my Disco classes grew smaller.

The end of my dance career seemed right around the corner.

The worst part of it was my inability to grasp what

had caused this bizarre turn of events. My

helplessness was driving me to madness. Why?

It made no sense.

Since there was no Internet in 1979,

it was not until I

began writing my book that I began to research the whole story.

As it turned out, the behind-the-scenes tale of Urban

Cowboy was amazing. I doubt you will ever read

a stranger story in your life.

|

HOUSTON'S WESTERN TRANSFORMATION

|

|

Before we begin the

background story of Urban Cowboy, let's read this article

about Houston's Western Transformation again.

|

| |

|

C&W

Nightclubs Riding High

Written by Michael Demarest

Time Magazine, 1981

In 1975 Houston had at most a dozen Cactus

Cabarets.

By the time 1981 rolled around, Houston now had more than 300, few of which cared to

emulate Gilley's Dodge City outlaw style.

In February 1979,

McFaddin-Kendrick, a Houston-based conglomerate, opened

Cowboy, the city's first upscale Twostep saloon

after doing extensive market research. Following its success with

Cowboy, McFaddin-Kendrick

then went on to launch a national chain of 40 western barns that

mixed country music with disco music.

Cowboy's success revolutionized the club industry. Before then, there was no such thing as a "classy"

country place. It used to be your choices ranged from

your standard

country dump #1 such as Gilley's to your standard country dump #2.

No one recognized the market for

"attractive" western clubs even existed. For that

matter, no

one had any idea it was possible to successfully mix disco

music with

country and western under one roof without people killing

one another. However, once Cowboy took off for the moon in

typical Space City fashion, everyone else jumped on the

bandwagon and opened Cowboy imitations.

The most successful,

Fool's Gold and San

Antone Rose, were located in affluent Houston residential

areas and, like Cowboy, catered to the Gucci gauchos.

Imitation proved to be the most sincere form of flattery.

|

WHAT EXACTLY IS A 'CACTUS CABARET'?

|

|

|

What a shame the

William Demarest article was not published in 1979.

Since I did not know the future, I was deeply immersed in gloom

at this stage. I was dying to know the

answer behind all of these unexplained changes, but no one

could help me.

Every now and then someone asks me if I would have done

anything different about my problem. Yes, if I had to

do it over again, I would have visited Cowboy

when it opened. As

it stood, I would not visit Cowboy until November

(two months further down the road from our current

point in the story).

As one can imagine, Joanne's Cactus Club was a

good example of William Demarest's "Cactus Cabaret"

reference. What a dump! Now here is the irony.

As it stood, I labored under the

misconception that Cowboy was just another

dreary, run-down Dodge City honky tonk that looked just like Cactus Club.

Such was not the case. In reality, Cowboy

was a veritable palace. But I did not know that

because I refused to visit the place. As we shall

see, I would pay a serious price for my Ostrich-style unwillingness to

face my fears.

|

We

have a saying here in Texas: "Don't put the Cart

Before the Horse."

This

is another way of reminding us the 'Effect' should

follow the 'Cause'. In other words, first you

have Saturday Night Fever, then you have

30 new Discos in Houston. Cause and Effect.

Such was not the case with Urban Cowboy.

The movie was not scheduled to appear until June 1980.

So why are all these Western clubs opening ONE YEAR BEFORE Urban

Cowboy?

I knew this mysterious Cowboy

had somehow initiated these 'Disco to Western'

changes.

I also knew John Travolta and Gilley's

were connected to the mystery. What I did not

understand was why the Disco clubs were in such a hurry to

close down and reappear as Western clubs.

When Cowboy first appeared in Houston at the

start of 1979, Disco clubs throughout America were doing

sensational business. This was true in Houston as

well. If Houston's clubs had maintained a Disco format

throughout 1979, I guarantee these clubs would have made a

healthy profit. Therefore the decision to switch to a

Western format one year early was totally unnecessary.

Hey, guys, what's the

rush?

For this reason, I was convinced some sort of mastermind was

responsible. Clearly these club owners were acting on

inside information.

|

|

Of course I was panic-stricken. It was not just my

career that was threatened, Disco was my entire life.

It was everything I lived for, my total identity, my only

claim to fame. The fear of becoming a nobody again haunted me

night and day. I ripped my hair out trying to

understand why these Disco clubs would shut down for a movie

that was not even filmed yet. Furthermore, the total

unanimity led me to believe these club owners knew

something that I didn't. If one or two clubs had

changed their spots, I could understand that. But

thirty clubs? Maybe even forty clubs? Good

grief, I was witnessing something akin to a buffalo stampede!!!

Making things even weirder, no one seemed to care about

Urban Cowboy, at least not in my circles.

Given zero interest in Western dancing among the people I

knew, on

the surface this stampede seemed like a huge gamble.

Disco was making Big Money in 1979, so why trade a sure thing for an unknown?

My conclusion was that these dance club owners had to know

something exclusive only to them. What could it be? Since these developments made no sense, I

developed a theory that something was going on behind the

scenes that no one but a select few here in Houston were in

on. There was someone out there, some sort of 'Wizard

of Oz' who orchestrated these changes.

But who was it? Who could it be? Tell me his

name so I could go shoot him!

|

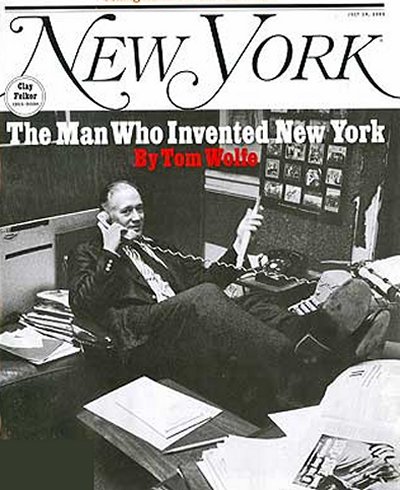

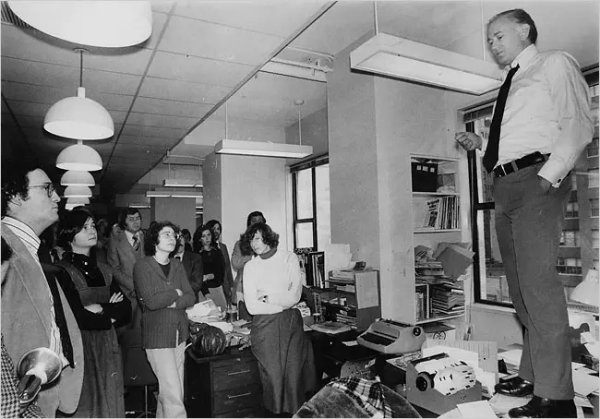

CLAY FELKER: THE MAN WHO

INVENTED NEW YORK |

|

Rick Archer's Note:

Before we begin, please keep in mind

I wrote my story about Clay Felker 40 years after the events

described. What I have written is based entirely on

snippets culled from various Internet stories.

Considering there is not one piece of first-hand knowledge

involved here, I apologize for any inaccuracies. That

said, I think the story I have shared is pretty close to

what took place at the time. Although the Reader may

recall I covered these details at the start of my book, I

hope you won't mind if I review the story for better

understanding.

|

As founder and editor of New York

magazine, over the years Clay Felker published one

ground-breaking story after another. Often referred to as 'Mr. New

York', Felker had three great talents. First, he

hired the best writers in the world. Second, he threw

the most lavish parties New York had ever seen.

Celebrities and politicians craved an invitation.

During those parties, Felker and his talented writers made

sure to pick up on the latest gossip and use it to their

advantage. Third, Felker had a gift for spotting a

good story. Nancy Newhouse, a senior editor in the

early years of

New York magazine, once said this about Clay Felker:

"I have never seen

anyone who was as open to his intuition as Clay was. He

had no barriers between his intuition and himself. Most

of us have all kinds of defenses. But with Clay, there

was no barrier. Sometimes he was wrong, but he was right

enough of the time, spectacularly right, that it was

astounding."

In other words, Clay Felker was the guy with his finger on

the pulse of the Greatest

City in the World. Or, as Tom Wolfe put it, he was the Man

Who Invented New York.

Clay Felker was famous.

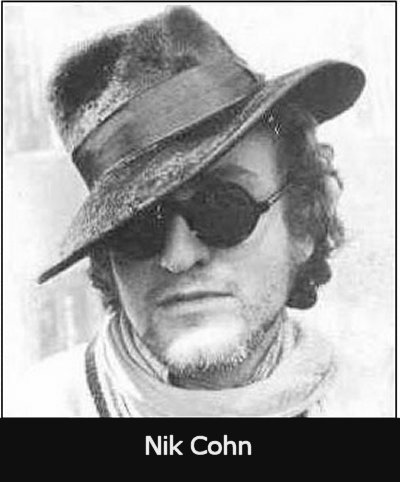

He was,

a major Somebody. However, at the height of his career, a

Nobody named Nik Cohn used Felker as springboard for one of the greatest scams in

journalism history. This is a great story, but why is

it relevant to my book?

Rick Archer owes his entire dance career to this tale.

|

|

|

In a 2016 article written for The Guardian,

Nadia Khomani had this to say about Nik Cohn:

"Saturday Night Fever was released in 1977, and has since

grossed $285m worldwide.

The soundtrack became one of the

best-selling film albums of all time after staying at #1

for 24 consecutive weeks, reinvigorating the Bee Gees' music

career in the process.

John Travolta became one of the

youngest actors ever to be nominated for the best actor Oscar.

Decades

later, not many people remember that this phenomenon was down

to one man: Northern Irish rock critic Nik Cohn thanks to

his story Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Nights in

New York magazine."

|

Catapulted to fame when Saturday Night Fever

became a smash hit, Nik Cohn began living the high

life. Nadia Khomani captured

Cohn's upgraded lifestyle in vivid fashion.

"Picture it: A writer pens a magazine article, an instant

sensation. Producers come calling, he sells the rights for

tens of thousands, the tabloids give him a nickname,

acquaintances greet him as a friend, checks flood in, he

attends the premiere of his film in Los Angeles with a

famous disco singer on his arm. It's glitzy, it's glam, it's

Hollywood, baby. But as he makes his way through the frenzy

outside the theatre, through security, paparazzi and

screaming teenage girls, he is filled with moral panic. Why?"

What is this 'Moral Panic' Ms. Khomani refers to?

In 1997, 20 years after his glory days, Nik Cohn confessed he had made up the entire story

and slipped the counterfeit tale past Clay Felker.

That was pretty slick, but the real pay-off came when Cohn

turned around and exploited producer Robert Stigwood for a

bonanza that was the stuff of dreams. Stigwood had

made a mistake. He had signed Travolta to a Million

Dollar contract only to find out after the ink dried that

Grease was not available to be filmed for

another year. Spotting Cohn's fake story in New

York magazine, Stigwood knew instantly Travolta would be

perfect as the moody dance stud with a big chip on his shoulder.

|

|

So how exactly

did Nik Cohn pull this off? He had the

advantage of inside information.

Back in England, Cohn

had been hanging out with a famous rock group known as

The Who ('Who are You', 'Pinball Wizard').

Robert Stigwood was their manager. During the filming

of Tommy, a rock musical based on an album

recorded by The Who, Cohn was invited by the band's leader,

Pete Townshend, to visit the set. That is how

Cohn met Bill Oakes, an RSO music executive (Robert

Stigwood Organization).

When Stigwood relocated

his operation to

New York City, Oakes invited Cohn to come along and sleep on

his couch till he could find a place of his own. Cohn

parlayed his connections with RSO into a job as music critic

for Felker's magazine. That led to an assignment to

check out the dancing at a Brooklyn nightclub. As it

turned out, there was street brawl right in front of the

Disco. Nik Cohn was too afraid to even get out of his

taxi. So he watched a while, then decided to use his

imagination to write a fake story based on characters he had met in

the London Mod Scene.

After he

finished, Cohn handed the article to Bill Oakes and asked him to

take it over to RSO as a potential movie script.

Kevin McCormick

was

in charge of film development for Robert Stigwood. The

moment McCormick read the

story, he saw the potential

and engaged Nik Cohn in preliminary talks. Cohn agreed to $10,000 for an option on

his article with Kevin McCormick on board to

produce the movie if Stigwood approved. However the deal had not been

finalized.

When Cohn told

his buddy Bill Oakes about McCormick's interest, Oakes said, "Before

you go back, why don't you see if you can get your story published? Stiggy

(Stigwood) is a lot more likely to pay

attention if you can get it into New York magazine

first."

|

|

|

Cohn was an aggressive guy. He could have waited to

approach Felker at work the next day, but he was impatient

to get Stigwood on board.

That night Cohn went to the trouble of tracking

the editor down while Felker and several friends ate dinner at a posh New York

restaurant.

Imagine the chutzpah. Try to

picture the nerve it took for this

scruffy street hustler to walk uninvited into a restaurant

and interrupt his boss while Felker entertained celebrity friends. Right in the middle of the meal,

some lowly unknown music writer breaks in to pitch a story

about a bunch of poor Brooklyn teenagers who liked to dance.

Startled, Felker decided to listen as Cohn explained that his story depicted the dance

world of disadvantaged teenagers who lived in Brooklyn.

Every Saturday night this tight-knit group wrapped their entire lives

around Disco dancing in the clubs.

To Cohn's dismay, Felker

laughed in his face. Ridiculous! Then

Felker rubbed it in. With Cohn standing there, Felker

embarrassed the young man by asking his dinner guests what

they thought about a story covering

the Saturday night dance habits of young working-class

Italian-Americans.

Understandably these important

cognoscenti scoffed.

Who gives a flip about a bunch of teenagers who like to dance on Saturday

night? They had heard it all before. This lame

story could just as easily been written about dancing to

surf music in Beach Blanket Bingo.

Hearing the scorn in his friends' voices, Felker told Cohn to forget it.

To him, Disco music was a fringe phenomenon

exclusive to boring lower-class youth. No one who read

his magazine could possibly be interested.

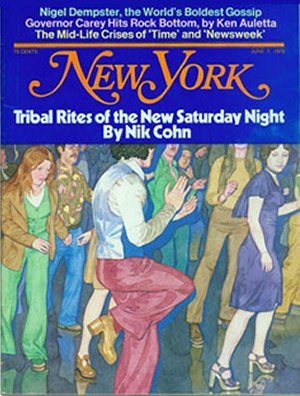

Cohn was crushed, but he wasn't going to give up easily. He

went behind the editor's back to speak to Felker's business partner Milton Glaser.

Glaser liked James McMullan's artwork so much he decided to

champion the story. Despite mixed feelings, Felker

gave in and let the story run. Nik Cohn's

story, Tribal

Rites of the New Saturday Night,

was published on June 7, 1976.

|

The moment

Cohn's Disco story was published, Bill Oakes made sure

a copy of the magazine landed on Stigwood's desk.

Timing is everything. At the exact moment beads of

sweat began pouring off Stigwood's brow over his

Grease dilemma, Stigwood noticed Cohn's Disco

story right in front of his nose. Stigwood recognized

instantly that he could plug Travolta into this story, but

then he panicked.

"Oh my God," Stigwood thought, "what if someone

else sees the potential in this story?"

Here's the funny thing.

What potential? Disco was hardly a household

word in those days, but Stigwood did not know that.

All he knew is Travolta needed a movie to star in this very

minute and this story had appeared out of nowhere like a

gift from the Universe. Although the details are

murky, there is reason to believe Oakes was keeping Cohn

posted on the developments. Look at it this way.

It was quite a coincidence that Cohn wrote this story at the

exact same moment Stigwood was agonizing what to do about

Travolta. That is why I sometimes wonder if Cohn knew

about Stigwood's 'Travolta problem' ahead of time

when he wrote his fortuitous story.

In 2007, Sam Kashner wrote a terrific story about

Saturday Night Fever in Vanity Fair.

One particular item caught my eye.

"Back in the

Seventies it was almost unheard of to buy a magazine

article for a movie, but 'Tribal Rites' attracted enough

attention that producer Ray Stark (Funny Girl) and a few

others bid on it."

Sam Kashner made the point that Robert

Stigwood was not the only person who noticed the dramatic

potential of Nik Cohn's story. My theory is that once

Cohn got his article published, he pitched his story to

every producer in town, thereby driving up the price.

One thing for sure, Oakes came back and told Cohn that

Stigwood was hooked on the story. "You won't

believe this, but Stigwood told his lawyer he thinks this

movie will make a hundred million!" Oh

really? Since the deal with McCormick had not been finalized,

once he knew about Stigwood's interest, Nik the Slik raised the price. Cohn let

it be known to all concerned that another producer had read the story in Felker's

magazine and was really interested. Imagine that. "Gosh, I'm

sorry, but my price tag has just gone up."

Hmm.

Stigwood's lawyer

smelled a rat.

Sensing they were being hustled, the

lawyer suggested

Stigwood back off. Stigwood would

not hear of it. After all, Stigwood's intuition told him

this movie could be worth a hundred million

dollars.

Convinced he had to have this story at

all cost,

Stigwood

said,

"I'm going to pay the kid whatever

he wants!"

After telling

the lawyer he would handle it himself,

Stigwood

nailed

down the deal by

offering Cohn

the moon and the sun.

First

Cohn was paid $90,000

for rights to his story. Then Stigwood gave

Cohn

first

shot at writing the screenplay for a guaranteed $150,000.

It did not stop there. Cohn negotiated percentage points

for the

upcoming soundtrack album.

This was unheard of. Yes, musicians got

percentage points, but never a writer. It had never been done before.

However, Cohn had

seen how much money The Who had made from

Tommy. Well aware he had the man over a

barrel, Cohn used his street smarts to con

Stigwood.

Who can imagine how much money Cohn made

once the music album became a best-seller? Estimates pegged it

at $500,000, maybe more.

What an incredible

stroke of luck! The

intricate timing caused by Stigwood's dilemma had transformed Cohn's story from a $10,000

windfall into a half-million Bonanza. Read that again:

Half a million for a fake story. It was the scam of

the century.

|

THE MOST BITTER MAN IN

AMERICA |

|

Rick Archer's Note:

If I had one wish, I would have loved to interview Clay

Felker. I combed the Internet high and low for any

sort of insight into his reaction after getting flimflammed

by Nik the Slik. Unfortunately I found nothing, not

even a tidbit. Since Mr. Felker passed away in 2008, I

suppose his private thoughts will follow him to his grave.

That said, I believe I know enough about this story to make

some educated guesses. Just remember to take

everything I say with a grain of salt. I do not wish

for anyone to mistake my conjectures as "Fact".

Let me start by explaining why I am so fascinated with Clay

Felker. First of all, I owe my dance career to this

man. I am not going to say why just yet, but take my

word for it. Clay Felker is the man who did more for my dance

career than any other person. I would be more grateful

if he hadn't caused me an

untold amount of misery by instigating Houston's Western

Transformation without telling me what he was up to.

However, since we never met, maybe I should be more

forgiving.

In addition, I have a deeply personal reason

to explain my interest. I would like to ask Mr. Felker

if he believed in Fate like I do.

Let me start by reminding everyone that my former boss,

Lance Stevens, called me "The Dance Teacher who Couldn't

Dance". It wasn't a very nice thing to say, but at the

time it was true. In the first year of my dance career

I was woefully inadequate. Nevertheless, right before

his eyes two really strange things happened. Slowly

but surely I turned into an excellent dancer. Practice

makes perfect. But even more remarkable was how my

Disco program grew to gargantuan proportions that dwarfed

the best Stevens could do.

How do you suppose that made my boss feel? Bitter.

That would be my guess. Stevens surely

had to wonder how a clod like Rick Archer pulled it off.

Was he suspicious of my Lucky Breaks? I speak of

things such as the Crossroad Synchronicity, the Partner

Dance Crisis, my chance meeting with Deborah Gordon, my

chance meeting with Glen Hunsucker, and the incredible

contributions of Victoria. I have tried very hard to

explain how I would have been hard-pressed to succeed on my

own merits. Stevens could see with his own eyes how

inept I was. So what could explain

my phenomenal success? Well, you already know my

answer. I gave credit to God and Fate. But I

doubt Stevens was wired to think that way. The

poor man must have been mystified to see me succeed against

all odds.

Lance Stevens saw himself as the best dancer and best

instructor in the city. He was the self-described "King

of the Whip". One picture after another lined the

wall trumpeting his impressive victories in major Ballroom

dance competitions. Stevens was at the top his game only to

see some snot-nosed brat steal his thunder. How did he

explain this unlikely development to himself?

|

I

came to see Clay Felker as a counterpart to Lance Stevens.

Felker was considered a genius.

The Internet is full of accolades for Clay Felker. I

read article after article praising his brilliance. Some say Felker was the man

who invented New York City thanks to one insightful story

after another. He hired gifted

writers whose articles gave the city its cachet. His

co-publisher Milton Glaser created the "I love New York"

logo. Felker was respected throughout the country as a

very clever guy.

And yet in the story that launched Saturday Night

Fever, one of the biggest stories of his career, Felker was totally fooled. He never saw it coming.

Here was a story that created a national phenomenon,

but Felker did not deserve a bit of credit for this

ground-breaking article. He wanted to reject it! Considering this was the man who was 'spectacularly right' most of the time,

it must have blown his mind to miss this one completely.

In a manner eerily similar to Lance Stevens, Felker was at

the top his game only to see some snot-nosed brat steal his

thunder. Although it is highly unlikely

Felker realized Cohn's story was a complete fraud at

the time, one can imagine the misgivings he felt when this

goofy story he had ridiculed magically skyrocketed to become a

major motion picture.

|

|

|

Clay Felker's decision to publish Nik Cohn's false

Disco narrative in New York

magazine was the spark that created the nationwide

Disco phenomenon. Everyone praised him for his wisdom

to anticipate this unknown breaking trend. Hmm. Do you

suppose this development gave him any

satisfaction? I doubt it seriously. Once

Felker realized he had been badly outsmarted by a street

punk, he took little pleasure

in breaking one of the biggest stories of his career.

The nightmare did not stop there. Try to imagine how

Felker felt when the film proceeded

to make everyone wealthy and

famous beyond their wildest dreams. Everyone but

Felker,

that is. Clay Felker, the mightiest clairvoyant of all,

Mr. New

York, New York himself, had been reduced to a footnote

by a nobody.

I

wondered if Felker benefitted in any way from Cohn's story. In my research, I was unable to find a single story to

suggest Felker directly profited from the cultural phenomenon

generated by Cohn's Disco story.

Did Felker make any money? I doubt it. Does the

editor of the Houston Chronicle get money from an

award-winning expose printed in his paper? Probably

not. I could be

wrong, but I don't think Felker made a dime off

Saturday Night Fever. Meanwhile Nik Cohn

became famous and made an estimated half million dollars.

|

Perhaps Clay

Felker was too hard on himself. From my perspective, he never had a chance where

Saturday Night Fever

was concerned.

No one could have seen this result coming. That is

because it was Supernatural! If you think I am

kidding, nope, not this time. Robert Stigwood had John

Travolta and the Bee Gees in his pocket with no idea what to

do with them. Poof! Like the answer to a prayer,

the perfect story magically appeared out of nowhere. The luck of

having the perfect actor, the perfect story, and the perfect music

all at the same time was unbelievable. Thanks to this

Synchronicity, the Arrow of Destiny was pointed at

Robert Stigwood, not

Clay Felker.

Nik Cohn

had badly outsmarted Felker by planting a bogus article in

his magazine. Gaining credibility from getting his story

published over Felker's misgivings, Cohn's story attracted so

much interest that he was able to leverage Robert Stigwood

into the big payday. Then Stigwood turned around and waltzed off with the Grand Prize.

I imagine Felker felt badly used. No doubt his pride was hurt

as well. Given Felker's sterling track record, I really felt

for the guy. Despite his razor-sharp instincts for spotting unusual

lifestyles,

a story worth $285 million

(SNF box office)

had passed right

under the nose of the Great Trend Spotter. Even

more pathetic, the story was totally fictitious. If

Felker had been on his game, no doubt he would have caught

it. Instead Felker had to live with the humiliation of

being tricked by a street hustler (and the worst was yet to come).

|

|

So here is the

question I wanted to ask.

"Mr. Felker,

when you got hoodwinked, did it ever occur to you that you

were Cosmically Blinded so Nik Cohn could attain his

Destiny?"

I am just

teasing. I would have had too much respect for Clay Felker to

assume I have the right to ask such an impertinent question.

Nevertheless, in manner similar to Lance Stevens, surely

Clay Felker had to wonder how Nik Cohn, a menial staff

writer for whom he had little regard, managed to pull off a

half-million dollar score.

How do you suppose

Mr. New York felt about this? Personally, I think the most bitter man in America had to be

Clay Felker.

|

Readers may

recall I am fond of an Arabic Proverb known as "Two Days".

This proverb suggests that Life consists of alternating

cycles of Brightest Day-Darkest Day, Good Luck-Bad Luck.

When it is your Brightest Day, you can do no wrong.

When it is your Darkest Day, nothing seems to go right.

Something I have

always found fascinating is how people who are truly gifted

seem to have periods of their life where they really

struggled. Then one day I came across a unique J.K.

Rowling quote.

"Talent and intelligence will not inoculate anyone

against the caprice of the fates."

To me, this

quote suggested that we all are going to experience

hardship, even people with money, privilege, talent,

intelligence, and friends. Obstacles are programmed

into our life and we have to deal with them.

Currently in our

story, Stigwood, Cohn, the Bee Gees and Travolta have

embarked on their Brightest Day. Clay Felker?

This is his Darkest Day.

|

|

|

The main reason Nik Cohn got

away with highway robbery is because Clay Felker was badly distracted.

Felker was in the fight of his life trying to maintain control of

his magazine.

Felker was up against a

ruthless billionaire named Rupert Murdoch. Making matters worse, it was his

own fault for letting the fox inside the henhouse.

Of course we have to ask why would Felker let his guard

down. If you agree with Joanne Rowling, Talent and

Intelligence are no guarantee of protection against a loss

of Common Sense.

Felker was a terrific

editor, but he had one major weakness... he liked to spend

other people's money. Felker's expenses were

so exorbitant, they out-stripped the magazine's resources.

His lavish spending on limousines, office space, costly

parties and personal

chefs drew heavy criticism from his magazine's board of directors.

One day Felker demanded they buy him a house in the

Hamptons so he could throw bigger parties. That was the last straw. Clay Felker had

grown too big for his britches.

In 1976, New York was going broke. Fed up with

his

rampant spending, the board of

directors told Felker to find a solution or start looking

for another job.

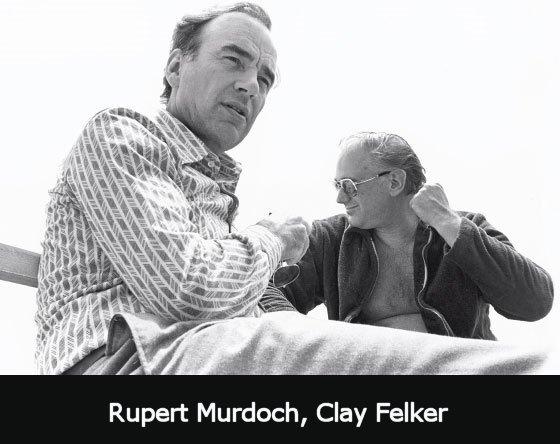

Clay Felker had recently been introduced to Australian media

mogul Rupert Murdoch by Katherine Graham, publisher of the

Washington Post. Graham asked Felker to

show the new kid in town around New York. The two

became fast friends, lunching downtown, lounging seaside in

the Hamptons and discussing mutual business ventures.

|

In November 1976, Felker made a bold move.

Taking note of Murdoch's deep pockets, Felker mentioned his boardroom

problems to his potential sugar daddy. Felker casually asked if Murdoch might be

interested in making an investment in the magazine.

Murdoch's eyes lit up immediately. Felker's suggestion was akin to asking the friendly

neighborhood fat boy to

watch his hot dog for a while. Murdoch smiled

politely, then offered an invitation. "Why,

sure, Clay, why don't you drop by the beach house this weekend?

Let's

have a talk!"

Felker must have been in some sort of fog. Or perhaps

he had fallen under the spell of 'Cosmic Stupidity'.

You knew I was going to bring that up, didn't you? Ordinarily a shrewd man with killer instincts, Felker

had missed what Nik Cohn was up to and now he missed

what Rupert Murdoch was up to as well.

Felker

did not seem to understand was that Murdoch was looking to

expand his media empire. That was why Murdoch had come to

New York in the first place. Murdoch had started with

the purchase of the New York Post,

a blue-collar tabloid. Now for his next conquest, wouldn't it be nice to have a

way to reach the city's wealthy movers and shakers?? Thanks to Felker's big mouth, Murdoch had just realized

the smart,

sophisticated New York magazine was in play. Murdoch

licked his chops.

Meanwhile Felker remained blind to the danger. He was

so certain that Rupert Murdoch was a well-meaning buddy,

Felker poured his heart out to Murdoch during that fateful

weekend in the Hamptons. Journalist Susan Braudy

offered this startling eye-witness account:

|

"I had dinner with

Rupert and Clay

at

Murdoch's rented house in Southampton. I was there

as a weekend houseguest of Clay Felker, the

publisher of New York magazine. Murdoch's

daughter and son served steak and fresh baby peas. Flawlessly

tasteful. Intimate. A stealthy trap. For Murdoch, the

dinner party was a high-level espionage mission.

Clay had no

inkling that Murdoch was secretly positioning himself to

steal New York magazine out from under him. Clay was loquacious

throughout the meal. He explained Manhattan things to

Murdoch who Clay clearly saw as a bit of an Aussie rube. Clay

waxed eloquent about his writers Aaron Latham and Gail Sheehy (who were

also present at the meal). He explained my presence in

terms of Ms Magazine which he had helped

launch and where I wrote and edited.

Clay bragged about

his fabulous parties. He confided to

Murdoch that he got his best stories by listening to

dinner party conversation. He was oblivious that

this time it was Murdoch who was doing the listening,

turning the tables so to speak. Clay got no stories

at this dinner because Murdoch said almost nothing. He

asked one or two flattering questions and that was it.

Murdoch was doing to Clay what Clay usually did to

everyone else... listen.

A month or so

later, Murdoch seized New York magazine

and instantly fired Clay despite assurances to the

contrary."

|

|

Clay Felker had been out of his mind to speak so candidly to

the fox.

Andrew Tobias, one of Felker's writers, had this say:

"Clay was not great with money. He was always

asking me for financial advice like how he could stint

on his editorial package. Clay's bread and butter

was creativity. The stories and graphics and

writing meant far more to him than profits. Then

came the day he met a terrific young Australian

publishing tycoon. Clay told me, "Andrew, you've got to go meet this guy!"

Clay assumed he was setting up Murdoch to be

his shining knight. When Clay sent me over to visit Rupert Murdoch,

Murdoch ended up interviewing me about the magazine.

That's when I got that funny feeling. Sure enough,

to Clay's

consternation, Murdoch grabbed the magazine right out from under him."

Once Murdoch realized Felker had alienated the board of

directors, he saw his opening. At the same time

Murdoch was sharing meals with Felker, he was negotiating

behind Felker's back with the magazine's majority

shareholder. Murdoch waved big money at the Board and

they took it.

Clay Felker never saw it coming until it was too late.

Once he realized what Murdoch was up to, Felker tried to persuade

his friend Katherine Graham at the Washington Post to

intercede. When Katherine Graham learned of Murdoch's backdoor

dealings, she called Rupert Murdoch to beg him to

reconsider.

"Don't do this to the boy, Rupert. Don't destroy this boy, don't take this boy's

magazine from him."

Murdoch could

have cared less. Murdoch sensed

weakness. He was a shark and there was blood in the

water. Felker might be a great editor, but he was

a bad businessman. The moment Murdoch bought the

New York

magazine, he told Felker to hit the road.

Despite Felker's deep connection to his baby, Felker was of

no use to Murdoch. He didn't want Felker around.

A ship cannot have two captains.

Felker felt betrayed, stabbed in the back.

He expected Murdoch would help him acquire

New York magazine,

not take it for himself. He had trusted the wrong person.

Felker was down to one last hope.

His stable of talented writers

was deeply loyal. They threatened to revolt

if Murdoch fired Felker. However, the writers got nowhere.

Murdoch called their bluff. If they left, Murdoch said

he would replace them

faster than the furniture. There's always another

college graduate hungry to make their mark. Besides, try finding another job in

this market, especially after Murdoch put the hex on them. The revolt collapsed

faster than a punctured balloon.

Here is how Richard Reeves, one of Felker's stunned writers, put it:

"This was a time that

we all thought the power was with the writers,

with the creative people. We were wrong. In a way we

were forced to learn what

they already knew in Hollywood: That's not the way it is.

The power is with the money. While we wrote about

that all the time, and while Clay understood that fact

of life

intellectually, as a businessman I don't think he got it."

1976 and

1977 were tough years for Felker. He

was outsmarted by Nik Cohn, outfoxed by Rupert Murdoch.

The toughest blow of all was losing his beloved

magazine. When

Murdoch showed him the door, Felker was

heart-broken and devastated. He was also out of a job.

Humiliated, Felker

lost his pride, he lost his job, he lost his reputation

and he lost the most precious thing in the world, the magazine

he had created. Clay Felker had been synonymous with

New York magazine. But

not any more. People laughed at his downfall.

Clay Felker was called a loser, a chump.

|

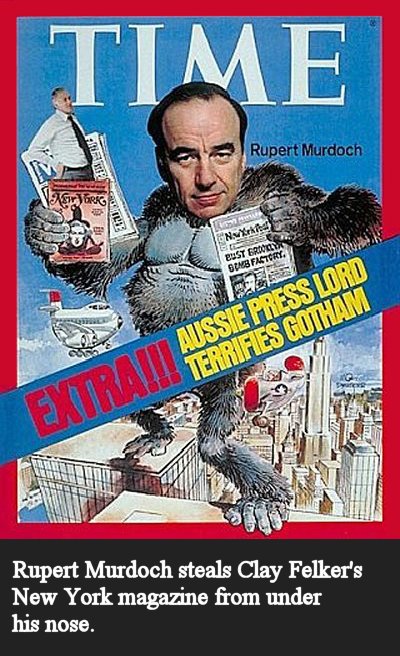

Media mogul Rupert Murdoch, a

supposed friend,

had

betrayed a gentleman's agreement in order to seize control of

New York

behind Felker's back.

After

Murdoch confiscated the magazine,

Felker was unceremoniously

fired. Not only did Clay Felker lose the most

important thing in his life, he was badly humiliated when

news of his

failure in the

nasty power struggle became public knowledge.

This was a painful blow. No one but

Felker knew the inside story how Nik Cohn had embarrassed him.

However, the

Murdoch situation was much different.

Felker's giant

reputation was badly tarnished when news came out how

Murdoch had tricked him. Imagine what it must feel

like to become the laughingstock in the media capital of the

world.

On a personal note, I was very drawn to Felker's story.

It reminded me of the dread I felt back when the

fall of Disco threatened my dance program. Quite

frankly, New

York was just as important to Clay Felker as my

dance program was to me. It was his baby, his reason

to exist. I also related to Felker's bitter defeat at

the hands of the cunning Mr. Fox. Clay Felker's big

mouth cost him his job the same way my big mouth got me

thrown out of graduate school. The knowledge that I

had caused my own downfall was searing, so I imagine Felker

was equally devastated. No doubt he was keenly aware

his self-destructive behavior had gotten him into this fix.

Brightest Day, Darkest Day. This was Felker's Darkest

Day.

Saturday Night Fever

was being filmed in Brooklyn at the same time that Clay

Felker was wrestling with Rupert Murdoch. Shortly

after Felker was fired in late 1977, the movie debuted in

December. At the exact moment

Clay Felker was thrown out, he was forced to watch helplessly as box office and soundtrack made

Saturday Night Fever one of the most lucrative films in

cinematic history.

This had to be the lowest moment of his

life.

Everyone who touched this movie got

rich. Nik Cohn came away with $500,000. Robert Stigwood made $300

million. Travolta and the Bee Gees rocketed to

stardom. Felker was aghast to realize he was the big loser

in this amazing bonanza. In particular, he seethed at

the indignity of letting Nik Cohn leapfrog to the

stratosphere using his unwitting shoulders for lift-off.

Bitter

at his fate, Clay Felker decided he had a score to

settle.

Feeling like a chump, it is fair

to assume Clay Felker sought redemption.

But what was he going to do about it?

|

|

Rick Archer's Note:

Keep

scrolling.

The story of Clay Felker's

comeback attempt follows below.

Thank you

for reading!

|

|

MAGIC CARPET RIDE

the disco

years

CHAPTER EIGHTY SEVEN:

REDEMPTION

Written by Rick

Archer

|

|

|

Rick Archer's Note:

'Casey at the Bat'

is the classic American metaphor for the dangers of complacency.

Mighty Casey is the best baseball hitter of all time.

He has never failed in the clutch. Casey is so

confident in his ability to hit the ball that he is unable

to fathom striking out when it matters the most. When he went to bat

for Mudville's big game, Casey was so sure he would hit a home run that he didn't

bother swinging at the first two pitches.

Unfortunately, when Casey

swung at the third pitch, he missed it completely.

Strike Three. Casey was out, game over.

|

In 2007,

Sam Kashner penned a detailed 17-page account about how

Saturday Night Fever

was made. Kashner dutifully added the name of every

single person involved in the project.

Writer Nik Cohn's name was listed prominently.

Rumor has it that Cohn made upwards of a half

million dollars in return for his unethical behavior

in sneaking a false story under Clay Felker's nose.

Producer Robert Stigwood's name was listed prominently.

Trusting his instincts, Stigwood was rewarded with

$285 million box office and $40 million soundtrack

based on a $4 million investment.

What about Clay

Felker? Without his permission to run the

story, Cohn and Stigwood would have never made their

fortune.

Considering the

thoroughness of Mr. Kashner's article, if Clay

Felker had been involved in the making of Saturday Night

Fever, we would suppose his name would have appeared,

yes??

In a 10,000

word article,

Clay Felker's name was nowhere to be seen. Well,

actually, change that. His name did appear

once:

"Cohn went back to the disco with artist James

McMullan, whose illustrations for the article

helped persuade Cohn's underwhelmed editor in

chief, Clay Felker, to run it. The title

was changed from "Another Saturday Night" to

"Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night," and a

note was added insisting that 'everything

described in this article is factual.'"

|

|

If we analyze

this development from a Mystical point of view, a

case can be made that Clay Felker's usual sharp

instincts were dulled by Cosmic Blindness.

Suffering through his Darkest Day, Felker's mistake

allowed Nik Cohn and Robert Stigwood to enjoy their

Brightest Day. Or we can ignore

the Mystic implications and just say Felker had a

bad day at the office. Distracted by his

problems with Rupert Murdoch, clearly Felker was on automatic pilot

when he published the Disco

story. Imagine his stupefaction when the story became important

to the tune of $280 million box office and $40 million

soundtrack based on a $4 million investment.

Felker

was undoubtedly fit to be tied. How

on earth could he have missed this Disco phenomenon? After

all,

wasn't Clay Felker supposed to be the ultimate trend-spotter?

Clay Felker was the man who prided himself in spotting

trends before all others. And yet the one time his

talent could have really paid off, Felker missed it. Disco

was a trend that had been placed right under his nose and

all he did was sniff with contempt. Now everyone

around him was getting rich and Felker had

absolutely nothing to show for it. Given that Felker

never made a dime off the cultural phenomenon that

defined the Seventies, I would imagine Clay

Felker felt badly used. I have to believe that

Clay Felker became obsessed with getting the chance

to set things right.

|

|

Rick Archer's Note:

Before we begin, let me remind everyone that my story about Clay Felker is based on

best-guess insights gleaned from stories found on the

Internet. I put myself in his shoes and tried to

imagine what went through his mind. Given that I have

no first-hand knowledge, I cannot promise

100% accuracy. However, I think I came close. Personally, I

find the story of Felker's Comeback

Trail to be remarkable.

|

|

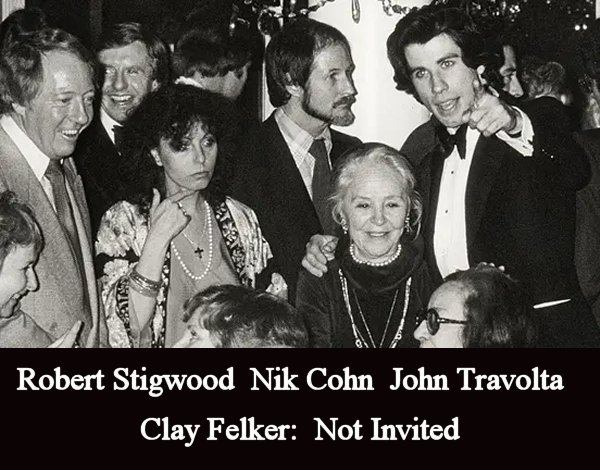

One of my

favorite stories about Saturday Night Fever

was the L.A premiere party on December 7, 1977.

Faces in the crowd were all sorts of celebrities

including Farrah Fawcett, Chevy Chase, Jim Brown,

Michael York, Kristy McNichol, Carly Simon,

John Travolta, Robert Stigwood, and the entire cast

from the movie.

Sitting at home

that night in New York was Clay Felker. He was

not invited to the premiere. Why not?

Because he did not have a single thing to do with

the movie. Felker was not in a good mood.

For one thing, he was unemployed thanks to a certain

Mr. Murdoch. In addition, he was astonished at

the reception Stigwood's movie was garnering.

His mood grew worse when he heard this virtually

unknown movie had become a box office bonanza to the

tune of $280 million based on a $4 million

investment.

One also has to

wonder when he saw that Nik Cohn was there that

night accompanied by his date, the glamorous Yvonne

Elliman. To refresh your memory, Ms. Elliman

had a Number One hit on the soundtrack titled "If

I Can't Have You."

Nik Cohn.

Half a million. Yvonne Elliman. National

acclaim. That's Hollywood, baby. My

guess is that Felker wanted to murder the guy.

|

|

For all the success tales that weaved through the improbable

Saturday Night Fever saga, there was one

person who was left with his bat on his shoulder.

Clay Felker. He struck out. Try to imagine how Felker felt when the movie proceeded

to make everyone wealthy and

famous beyond their wildest dreams, everyone but him that

is. Clay Felker was proud man reduced to a

laughingstock. Start spreading the news... Once the

talk of the town, rumor had it that Rupert Murdoch and

Nik Cohn had outsmarted the great Clay Felker while Robert Stigwood had waltzed off with the Grand Prize.

Filled with bitterness, my guess is Clay Felker craved a

second chance.

I

doubt seriously Clay Felker ever got even with Rupert

Murdoch. However, I am

quite sure Felker wanted to get even with Nik Cohn.

He probably wanted to strangle the guy. Considering

Felker's extensive contacts, I imagine he knew a mob boss or

two willing to do him a favor. Probably the only thing

that saved Cohn's life was the fact that Clay Felker did not

yet know the Disco story was a complete fraud.

As for Robert Stigwood, I cannot see where Stigwood did

anything wrong. Yes, he paid a King's Ransom for the

fake Disco story, but that had nothing to do with Felker.

If there were hard feelings between Stigwood and Felker, I

remain unaware. However, I imagine Stigwood's uncanny

success wounded Felker's pride. It is likely that Felker wanted to prove he was

just as smart as Robert Stigwood.

The moral

of Casey at the Bat is to swing at every pitch because you might not get another chance.

1976 was the year that Mighty Clay Felker struck out.

Still smarting from letting the Nik Cohn story sneak out from under his nose,

I believe Felker craved a second chance. I would bet

money that Felker became obsessed with

payback. Felker had an idea. If Nik Cohn could trick him, then he could trick

him right back. He had a plan to beat Nik Cohn and Robert Stigwood at their own

game. As we shall see, Felker's plan had an element of genius.

Felker's first move on the comeback trail was to get a job

as publisher and editor of Esquire Magazine in

1977. This turned out to be a shrewd move. His

next move was to look for a way to hijack Stigwood's

lucrative

sequel to Saturday Night Fever before Stigwood did it himself.

How do you steal a Sequel? Good question. Stigwood

owned the legal rights to Saturday Night Fever.

No doubt Felker would be sued to oblivion if he tampered

with Stigwood's property. Felker decided his only choice was to

make some sort of 'Disguised Sequel'. Easier said than

done. How does someone make a Sequel that isn't a

Sequel?

Looking for an answer to that question became Felker's

burning obsession.

Felker knew if he could find the right vehicle, he had the contacts and the skill to

pull it off. Felker had just as many

show business contacts as Stigwood. In addition,

Felker knew the Saturday Night Fever formula

by heart. Throughout the filming in Brooklyn,

Felker occupied a catbird seat which allowed him to

study every move Stigwood made. The problem was

finding the right vehicle. Fortunately, finding gold

in obscure stories was Felker's greatest skill. If the master trend spotter

could track down something similar to the

Disco story, he was certain he could emulate Stigwood's success.

|

After taking control of Esquire in 1977,

Felker began his search in early 1978.

Did anyone besides Felker know what he was up to? Perhaps

his wife Gail Sheehy and a few close friends, but Felker had

learned his lesson the hard way... Keep your mouth shut!!!

No more handing the farm to people like Murdoch.

So why the need for silence?

If Stigwood had the slightest idea what he was up to, the

game would be over. Felker smartly kept his cards to

himself lest this opportunity slip away. Even so,

Felker was not terribly optimistic.

Racing to beat Stigwood to the coveted Sequel,

Felker knew his secret plan was a long shot at best.

The thing about Darkest Day is that one's Brightest Day may

be right around the corner. Just remember to be

patient. Suddenly Felker got hot. He got a huge

break came when Stigwood decided there was no hurry to film

a sequel. Grease wrapped up

filming in California spring of 1978. Felker assumed Stigwood would

now turn his attention to making a Saturday Night Fever

sequel, but it did not happen. Since Stigwood had no idea Felker was

chasing him, he decided it was too soon to film the SNF sequel.

Instead Stigwood turned his attention to making Sgt.

Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, a 1978 musical mishmash starring the Bee Gees.

The irony here is that Grease marked the end

to Stigwood's Brightest Day. Now it was time for his

Darkest Day to begin. While Stiggy was in the process

of making three of the worst movies of all time, Felker was

looking to steal his Sequel.

|

|

Given this unexpected reprieve

by Stigwood, Felker scoured the land for some sort of idea.

This was not as easy as he expected. It took over six

months to find what he wanted. Finally Felker found

what he wanted. His inspiration took place on a summer

trip to Texas. In June 1978 Felker came to Houston to give a Journalism speech over

at Rice University.

Stigwood and Felker were on alternating Brightest

Day-Darkest Day cycles. Ironically, Felker's plane

touched down in Houston at virtually the same moment as one

of the great turkeys of all time, Stigwood's Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, was being

released.

Stigwood's star fell as Felker's rose.

The same held true for me. Felker's Darkest Day was my Brightest Day.

Stigwood's Saturday Night Fever launched my

career as a Disco teacher. Now Felker's

Brightest Day would create my Darkest Day. His grand

scheme to steal Stigwood's sequel is what put a premature

end to my career as a Disco teacher. Very curious how

this works, isn't it?

In June 1978 Felker was feeling dejected. Ever since the debut of

SNF, Felker had spent month after month scouring the land for a

solution to his 'Sequel' problem without success.

The clock was ticking and nothing had caught his eye.

The Houston airport made Felker's bad mood worse. As

he

walked through the terminal, Felker was surrounded by

neverending

images of

Saturday Night Fever. Now that the movie

had become the

reigning talk

of the land, Disco Inferno was raging. Felker was reminded of his

shame by Disco merchandise in every shop

he

passed. No doubt Felker

cringed each time he saw a picture of John Travolta to remind

him of his oversight. Wouldn't it be nice if he could

produce a movie of his own? Then he would be the one

to sell the merchandise in airports among other places. Gritting his teeth, Felker vowed to find a way to even the score or go nuts

trying.

|

Little did Felker realize

his luck was about to turn.

Felker was met at the airport by Bill Broyles,

editor of Texas Monthly magazine,

and Mike Levy, the publisher. They were sponsors of the media event

being

held at the Rice University School of Journalism.

First the men took Felker to dinner. Then Levy

and Broyles asked him what he wanted to

do next. It was late, 10 pm. Was he tired?

Would he like to go back to the hotel?

Felker shook

his head. Felker said he had never visited Houston

before. Would the men mind showing him around the city?

Broyles and Levy were more than happy to oblige.

As the three men got into Levy's car, Broyles suggested they visit élan,

Houston's favorite Disco. élan was just blocks away from

Felker's Galleria hotel.

Visit a Disco? Felker nearly vomited.

That was the last place he wanted to go. After

Felker said he could not stand Disco, Levy decided to try a different look at Texas-style nightlife. On

impulse, Levy and Broyles

drove Felker to wild and wooly Gilley’s in

neighboring Pasadena.

The moment Felker walked in the door, his

eyes grew wide as saucers. This vast honky-tonk

featured a country band, country dancing, a mechanical bull,

punching bags, pool tables, and scores of urban cowboys on

the prowl for urban cowgirls.

This was it! The moment Clay Felker saw dozens of

couples dancing to western music, the tumblers fell into

place. Felker had just found what he was looking

for. Felker's instincts said Gilley's was the

honky-tonk equivalent of

the Disco featured in Saturday Night Fever.

Felker had just hit the Jackpot!!

|

|

|

Previously Nik

Cohn had been in the right place at the right time.

Now it was Clay Felker's turn. Gilley's had given Felker the second chance he prayed for.

Give the man some credit. Right now two thousand

people were participating in what had to be the most alien

environment imaginable to Felker's elitist Eastern

sensibilities. It took some genuine

imagination to see the next 'Saturday Night Fever'

amidst this beer-fueled honky-tonk madness.

Fortunately, Felker was not put off by the

strange sight. Not at all. Felker's vision was

filtered through a rose-colored lens known as dollar

signs. Felker smiled. He was back in the Game.

Here is what I like about this story. How many people

could visit Gilley's and see its potential?

It would never occur to me, what about you? How many

people have the ability to see a run-down,

smelly honky-tonk

like Gilley's and make it sound like the second coming of Xanadu? Don't ask me

how he did it, but

Felker threw Ugly

into his spin machine and made Badass

sound beautiful.

Felker was about to

singlehandedly create a

National Country-Western Trend out of THIN AIR.

|

Give

the man some credit. Felker had the advantage of

knowing what he was looking for. There's old saying: "If

a pickpocket were to see a Saint, he would notice only the

man's pockets." If you or I visited Gilley's,

we would see the bull, the beer and the brawling. Clay

Felker was said to have a gift for spotting things others

missed. His instant recognition of Gilley's

as a substitute for the Brooklyn Disco club that served as

the setting for SNF was the perfect example.

Apparently this search had been on Felker's mind for a long

time. I base this conclusion on the fact that Felker

instigated his plan the moment he returned to his Houston

hotel that night.

On the drive back to the hotel, Felker said nothing to

Broyles and Levy, his Texas

Monthly friends, about his vision. Now that he

had found his pot of gold, Felker determined that stealth

was mandatory.

|

|

Preparing to beat Robert Stigwood to the

punch, Felker wasted no time.

Felker needed a country-western story similar to the Nik

Cohn story and he needed it fast. Minutes after

entering his room, Felker called his writer

friend Aaron Latham

at 3 am.

"Aaron,

get on a

plane and get your butt down to Houston pronto!"

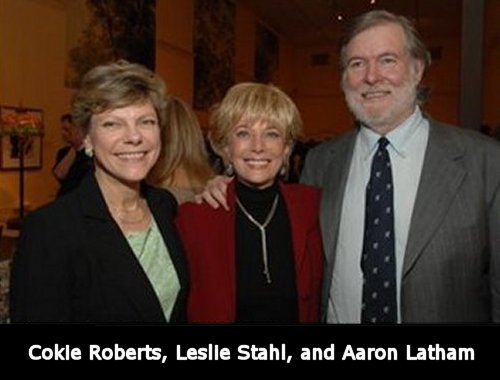

Aaron Latham was a Washington DC resident

married to

long-time

60 Minutes correspondent Leslie Stahl. Although

Latham was born in West Texas, he went to college at Princeton.

After graduation, Latham remained on the East

Coast to begin his career. Latham had been Felker’s primary

Watergate reporter at New York in the early Seventies.

Developing a close rapport, Latham and Felker became amigos. This was good

because Felker needed someone he could trust.

If one word of his plan leaked out, Stigwood might cut him

off at the pass.

Aaron Latham had never heard of Gilley's, but that

didn't matter. Following Felker's emergency phone

call, Latham made a beeline to Houston. He understood

his mission.

Felker wanted him to cut and paste Cohn's Disco story into the

C&W environment at

Gilley's. Latham quickly

fast-tracked the

script that would give birth to Felker's precious 'Sequel in Disguise'.

|

Clay Felker introduced Aaron Latham to Sherwood Cryer, co-owner of Gilley's. As

the two men walked around the club, Cryer advised Latham on

various angles for the Esquire article.

Sherwood

Cryer had a big smile on his face. Cryer enjoyed walking

this stranger through the cavernous paths because Felker

had confided in him. After swearing Cryer to secrecy,

Felker confessed he intended to make

Gilley's the C&W equivalent of Saturday Night

Fever. Based on that conversation, Cryer crossed his

fingers. It was crazy to believe, but Latham's story

might just put

Gilley's

on the national map.

During his tour of the club, Latham met some

interesting Gilley's

regulars including the colorful operator of the mechanical

bull. Unbeknownst to Latham at the time, the bull

operator was an escaped convict hiding in plain sight here at

the club. The man somehow persuaded Latham into riding

the mechanical bull. Latham must have been a brave man.

Since beginners were sure to be thrown, it

took real guts to get up on that violent machine.

Sure enough,

Latham was quickly thrown off the bull. Latham

was hooked. Undeterred, he spent the rest of the

day trying to master the mechanical bull. Bruised,

beaten, sore all over, Latham laughed at how seriously he had

taken the challenge. He vowed to

make this mechanical beast the surprise star of his story.

Latham

hung around

Gilley's for a month. He

interviewed everyone in sight and

rode the bull every chance he got.

The more people he talked to, the more he realized many of

them had grown up in the Texas countryside just like he had.

They had moved to the big city to chase factory

jobs created by Houston's booming economy.

The Gilley's regulars brought their country ways with

them. Boots, cowboy hats, trucks,

Wrangler jeans, and love of country music played a big part

in who they were.

These people were straddling two worlds, City and Country,

part-Urban, part-Cowboy.

Latham smiled. Referring to these

uprooted kickers as 'Urban Cowboys', Latham's story would revolve around young men,

many of them chemical plants workers, who spent every spare evening

trying to impress women by riding the mechanical bull and looking for love on the dance floor.

Latham stated “the cowboy, the most enduring symbol of our

country,” needed to be reinvented, generation after

generation, by people of the American West.

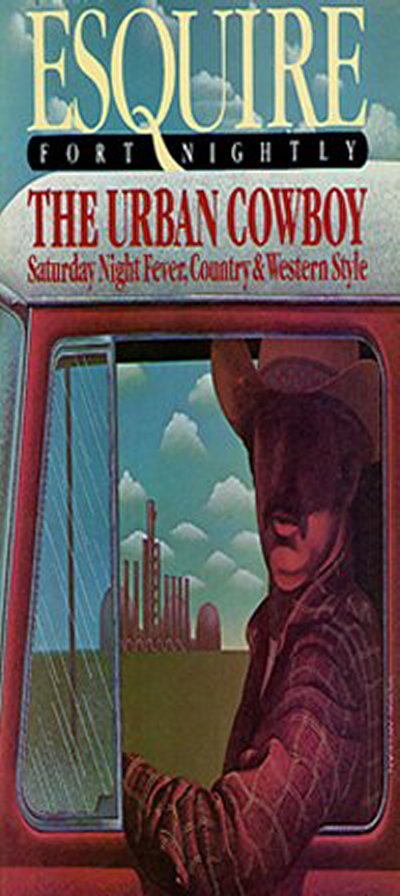

In September 1978, Latham's

Ballad of the Urban Cowboy and America's Search for True Grit appeared in

Esquire. This was undoubtedly one of the most pretentious

titles in history, but so what. The important thing was

Clay Felker's good sense to place a powerful subtitle

on the cover of his magazine:

'Saturday Night

Fever, Country-Western style'!!

Clay

Felker's headline worked like a charm. He made a

phone call to the same guys at Paramount Pictures who had

released SNF. The moment they got the

hint: 'Disguised Sequel!',

they took the bait. Then came Irving Azoff,

business manager of the rock band Eagles and several others.

He saw the chance to do for his

country music artists what Robert Stigwood had

previously done for

the Bee Gees. Azoff won the soundtrack bidding contest and began

producing Urban Cowboy. In a blinding

stroke of good fortune, John Travolta was available.

With Travolta on board, the success

of the movie was guaranteed. Pasadena, Texas,

became Brooklyn

with boots on, with a

hard-hitting story of directionless youth

with John Travolta as the Dancing Cowboy.

|

|

I

have to believe that Clay Felker's Urban

Cowboy project must have been deeply satisfying to

him. Considering the hardships he

had faced, Felker was

surely proud of himself. Putting this 'Disguised Sequel'

project together was an extremely clever move. But it

was not an original move. All Felker had to do was

follow the Nik Cohn-Robert Stigwood formula.

First, get control of Esquire, a substitute

for New York magazine.

Second, find a substitute for the Disco that served as the

location for SNF.

Third, hire Latham to replicate the Nik Cohn story featuring

directionless youth who spent countless hours dancing in a

club.

Fourth, publish the story in Esquire to drum

up interest in Latham's sto

Five, stress the Sequel aspect, "Saturday Night

Fever, Country-Western style"

Six, get John Travolta to emphasize the sequel angle.

Seven, contact the same guys at Paramount who had made a

fortune off SNF

Eight, sell the music rights to an Urban Cowboy soundtrack

item

Nine, market C&W clothing

Ten, publicize the movie to every media outlet in the

country using Felker's many contacts.

|

|

|

Clay Felker had the sense to

capitalize on his contacts in a very unique way. My

guess is that Felker began selling his Sequel to Hollywood

before Latham's story was even finished. There is ample circumstantial evidence to suggest Clay Felker contacted

everyone on his Rolodex regarding tie-ins to the movie.

It cannot be a coincidence that the

United States was inundated with Country-Western fashions

prior to the release of the movie. Nor can it be a

coincidence that the movie soundtrack was released well in

advance of the movie release. This, of course, was a

technique that Stigwood had introduced. In other

words, all the marketing was in

place long before the public had the slightest idea this project even

existed. Felker would go to orchestrate one of the

great pre-movie publicity campaigns in cinematic history.

This is speculation on my part, but it stands to reason that Clay Felker

tipped off Lance McFaddin. McFaddin was the director of Houston-based

McFaddin-Kendrick,

the company that specialized in opening fancy nightclubs

such as Foxhunter, élan, Ciao, Rodeo, and Cowboy.

Where do you suppose Lance McFaddin came up with his

ground-breaking idea to open a stunningly beautiful

counterpart to Gilley's, the ugliest club on

the planet? I am certain McFaddin used insider knowledge to

commission market research on the viability of an 'Upscale

Western Club'. Pleased with the survey results and privy

to the secret of Aaron Latham's upcoming Esquire

story, McFaddin decided to take a huge gamble and authorize

the expensive remodel of

Foxhunter necessary to create Cowboy.

McFaddin-Kendrick's February 1979 debut of Cowboy

became the opening

shot in Houston's Western Transformation. Once

the other club owners saw the overwhelming success of

Cowboy, they rushed to join the bandwagon.

So now we know the story behind the curious Disco-to-Western

chain reaction that ended my career as a Disco teacher. The movie box

office was $53 million, soundtrack earnings were $47

million. Although Saturday Night Fever

exceeded $400 million, this tidy $100 million payoff was

nothing to sneeze at. I think Urban Cowboy

did pretty well considering it was at best a rather tedious rip-off.

For that I tip my hat to Clay Felker, the Wizard of Oz.

|

|

|