Brevity and Brexity:

A Brief Look at English

History

Written by Rick Archer

rick@ssqq.com

Last Update: January 2017

|

Rick Archer's Note:

Due to my

2017 New Year's Resolution to become better known for my

Brevity, the following is an extremely brief article about Brexit and

Marla's upcoming 2017 cruise to Merry Old England... or, as

I prefer to say... the Texas Renaissance Festival on the other

side of the Pond.

Last October, Marla and I

visited Europe on our wonderful Greek Isles cruise.

During

our stay, we learned that Continental Europe is so mad at

England over Brexit, they don't want to have anything to do

with England anymore.

In their minds, England doesn't

belong in Europe. Go jump in the Pond.

|

|

Ireland and Scotland don't

want England anymore either. They never liked England to

begin with and they still don't. Both countries wish

England would go away and leave them alone for good. Do you

blame them? Of course not!

Keep in mind that Ireland

and Scotland both voted to stay in the European Union.

Ireland and Scotland hold England responsible for the Brexit

Fiasco. Plain and simple, Brexit was England's fault

entirely.

Unlike Donald Trump who

wants to make America Great again, Ireland and Scotland

would prefer to take the 'Great' out of Great Britain

and tell England where to put it. I guess Scotland and

Ireland aren't feeling very Greatful anymore.

Understandably, England is

feeling lonely and isolated. She needs a friend. As always

whenever England is in trouble, the erstwhile Mother of

America begins to look longingly in the direction of her

former Colonies in North America. Both the United States

and Canada have responded with open arms, but the USA has

been the more enthusiastic of the two. And why is that?

Donald Trump.

Donald Trump wants to take

Great from Great Britain and bring it over here to help make

America Great again. That has been part of his plan all

along. I am completely serious... feel free to tell this to

any news channel and I have no doubt they will accept it as

fact.

| |

I may be a hermit

these days, but I

still know stuff. For one thing, I

know that Texas is really big. It is three

times bigger than the United Kingdom.

However, in the interests of

humility, size isn't everything. For example,

Great Britain once ruled the world and Texas was

once controlled by Mexico. Some say it still

is. Build the Wall.

Speaking of Donald Trump, I am privy to inside reports that Donald... no stranger himself to Brexit-style elections...

has invited England to forget about Europe and consider

becoming part of North America instead. England is said to

be very tempted, especially after Trump promised to unite

the countries with a series of floating Trans-Atlantic golf

courses known as 'Putting on the Pond.' No sand

traps, but I hear the water traps will be very deep.

This is pure synchronicity.

By amazing coincidence, my dear wife Mystic Marla predicted

closer ties between America and England when she decided to

schedule her 2017 British Isles cruise. Although I have

never visited England, this place is close to my heart. My

family roots on both sides are about as English as they

come. I am part Welsh and mostly English.

I have a question. How many

of you know where 'America' got its name?

Believe it or not, the name

can be traced back to Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian mapmaker

and navigator who followed in the footsteps of Columbus.

After drawing some of the early maps of the New World, his

name became associated with the two continents.

|

|

| |

Sad to say, even though I am

English from top to bottom by heritage, I confess I do not

know much about English history. Curious, I decided to

start by figuring out where its name came from.

Was 'Eng-land' named

for some guy named Eng? Alas, I was disappointed. There

was no one named Eng.

The 'Britons' were to

the island as North America's Indians were to the Spanish,

French, and English. The Britons were the first occupants

of 'Britony' and 'Brittany'. The Britons

were there long before Christ. The Britons were the people

the Romans fought back in the days of the Roman Empire. It

was the Romans who named the island 'Britannia'.

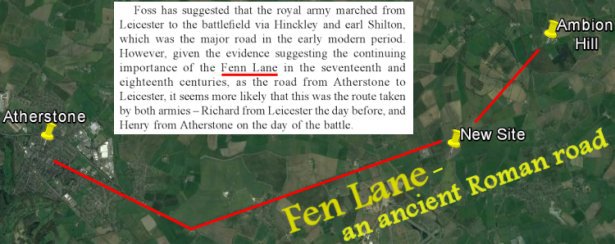

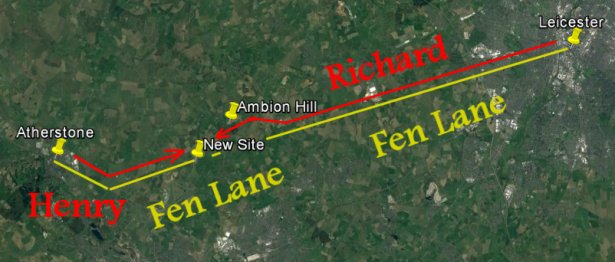

During their 400

years of occupation, the Roman influence on England was profound. In

that time, the Romans built walls,

cities, forts and roads. They

set the laws and the customs that people lived by. The

Romans brought a sense of order to a land that had only

known chaos. Prior to the Romans, Britain was a disparate

set of peoples with no sense of national identity beyond

that of their local tribe. In the wake of the Roman

occupation, every 'Briton' became aware of their 'Briton-ish (British)' identity. In other words, 'everyone

who belongs here is British and everyone who doesn't belong

here is Roman'.

The Romans did the island a

real favor by civilizing the place somewhat. Interestingly,

the Romans did the same thing for Spain and France.

England, France, and Spain dominated Europe for centuries

simply because the Romans had been there to organize

things. Oddly enough, Germany remained disorganized. Did

you know that Germany did not become a country until 1871?

Can you guess why it took them so long?

I know the answer... Germany

was the only major European area that the Romans were never

able to conquer. Consequently 'Germania' as the

Romans called it remained divided into hundreds of small

territories until late into the 19th Century. Can you guess

who began the German Unification?

Napoleon. Once Napoleon

kicked the Catholic Church out of 'Germania' and

confiscated most of its lands, Germany was finally able to

begin unification. I am not a big fan of warfare, but it

obviously serves a purpose. I find that both disturbing and

fascinating.

Speaking of warfare, the

Romans left Britannia when they had to go back and defend

Rome against those nasty German barbarians who were swarming

all over Western Europe in the 4th century.

| |

|

However, Rome would never be

forgotten.

Every generation of British

inhabitant that followed the Romans - be they Angles,

Saxons, Normans, Danes, Vikings - would strive to be the

next Romans. Each was trying to regain the glory of that

long-lost age when Britannia began the

long road towards being a unified island.

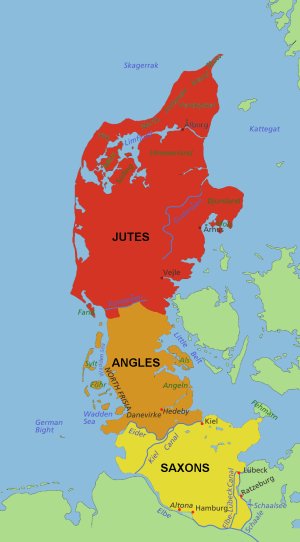

The Angles and the Saxons

were the Johnny-come-latelies. They were part of the barbarian

invasion of Europe that took out the Roman Empire. The

Angles and the Saxons were two separate tribes who occupied

adjacent territory in Southern Denmark and Northern

Germany.

For a while, the two tribes

were content to stay where they were. However, in the 5th

century, as more barbarians moved into

their area, they decided to

migrate. There are theories that

suggest the two tribes became aware of the vacuum created by

the departure of the Romans and moved west to take

advantage.

The Angles and the Saxons

carved out territory to call their own along the eastern and

southern coast of Britannia. Historically, the Anglo-Saxon

period denotes the period in Britain between about 450 and

1066, the dates of their initial settlement

all the way up

to the Norman

conquest.

The 'Angles' migrated

from Schleswig-Holstein, an area on the northern border of

Germany and the southern border of Denmark. The Angles

mostly settled in the easternmost part of the island. This

area became known as 'East Anglia'.

Just to the north was 'Northumbria',

another Angle-dominated area. The North Sea currents would

typically take any westward-bound ship leaving Denmark

directly to these two spots. The word 'Land' comes

from German. As one might guess, the 'Land of the Angles'

was eventually shortened to 'Angle-Land'

and then to 'England.'

The 'Saxons' were a

Germanic people who occupied the area in Schleswig-Holstein

just south of the Angles. Since they were used to occupying

land south of the Angles, the Saxons settled on

areas

to the south of East Anglia in places near to rivers or the

sea which could be easily reached by boat. The Saxons used

a river known as the Thames to occupy the settlement known

as 'Londonium' that had been abandoned by the Romans.

|

| |

|

The Jutes did not play as

prominent a role in English history as the better

known Angles and Saxons.

That is because the Jutes were

so well-established in the geographically favorable

spot where Denmark lies today that they felt less

pressure to move.

That said, some of their

people migrated as well. These travelers

generally settled in an area known as Kent.

|

| |

|

The Anglo-Saxons would

eventually take control of most of Britain, although they

never managed to conquer Scotland, Wales and Cornwall.

The word 'Folk' comes

from 'Volk', the German word for 'people'.

Think 'Volkswagen'. As the Saxons moved into

southeastern, southern, and central parts of the island,

they gave German names to their regions.

NORFOLK

were the north

folk.

SUFFOLK were the south folk.

The ANGLE

SAXONS settled in ESSEX, home of the east

Saxons

SUSSEX were the

south Saxons

WESSEX

were the west Saxons.

There were so many

of these Angles running the place that the island became

known as ANGLIA, then ANGLE LAND,

then ENGLAND.

The stretch of water

between England and France was used so often by the Angles

that it came to be called the 'Channel of the Angles',

later shortened to the ENGLISH CHANNEL.

Although France used the

same waters, the Angles... or 'Anglish' or English if

you prefer... used these waters a lot more for an obvious

reason. The English were a seafaring people... or they

would not have gotten to this island in the first place.

|

|

| |

|

One might ask if the word 'Angel'

and 'Angle' are related. Apparently not. 'Angel'

comes from the Latin word 'angelus' which comes from

the Greek word 'angelos'.

This makes complete sense

because the Angles were no Angels. In fact, the Angles were

a fierce, warlike people who would murder anyone who got in

their way. Sad to say, but the English were a cruel and

brutal people from the very start. Ask the Scots and the

Irish if you doubt my words. Or ask how many Indians were

massacred by English colonialism in India and North America.

France would no doubt also agree with

my assertion that the English were a rough bunch as well.

If ever there were two

countries that did not get along very well, that would be

England and France. Oh my gosh, those two have been going

at it for centuries. Did you know that France and England

are only 20 miles apart? At a spot near Dover (England)

and Calais (France), the distance is so short that people actually

swim across the English Channel. People with binoculars can

actually watch someone swim the entire distance.

This proximity has led to

many a battle between the two countries. At

one point France and England were

at war with each other for over 100 years. As a bit of

history, The Hundred Years' War was a long struggle

between England and France over who would succeed to the

French throne. The conflict lasted on and off from 1337 to

1453, so it might more accurately be called the '116

Years' War.' But that's not a very catchy

name, is it?

As it turns out, English

history is very interesting. So I

researched several of the highlights to include in this

article. However, before we begin, let's find out how

much you know about English history.

•

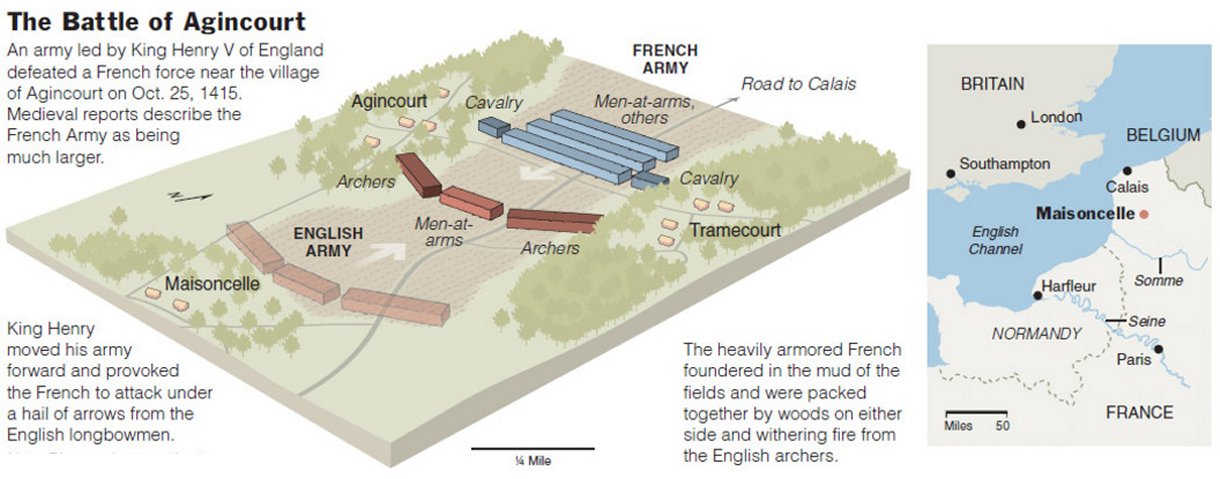

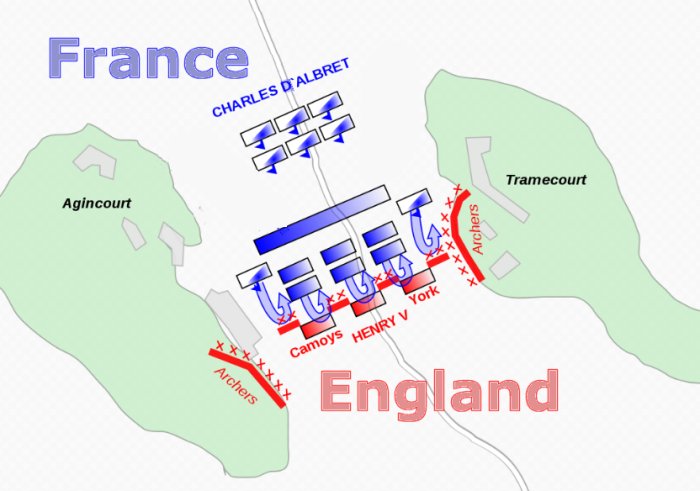

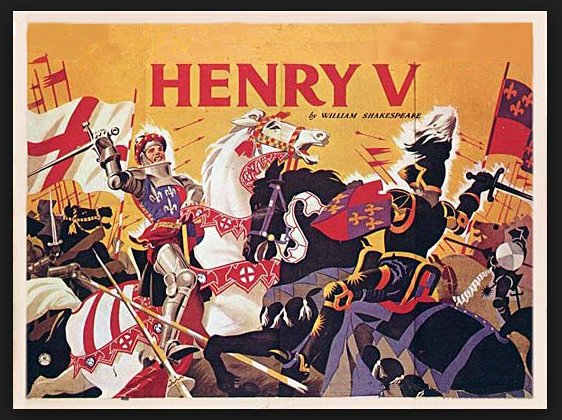

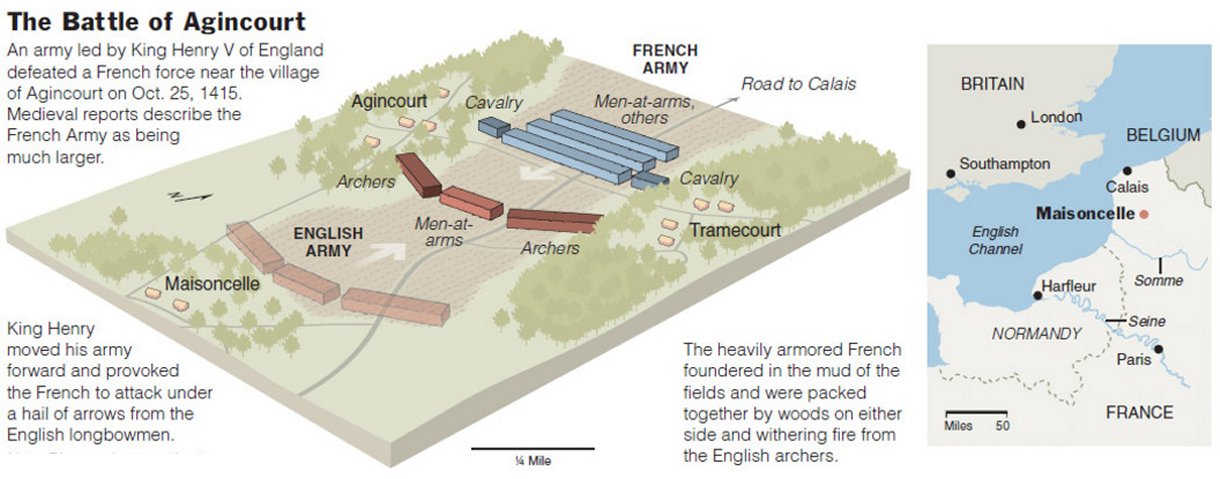

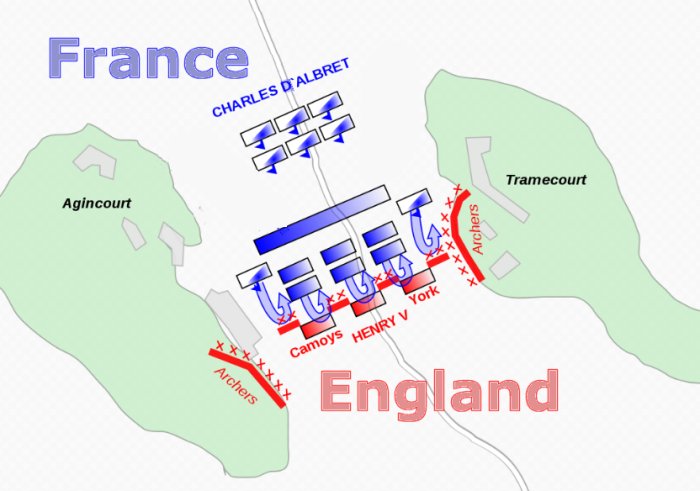

We will start with a

fun question. During the Hundred Years War, the most famous battle

in English-French history was won by England due primarily

to the Archers. Can you name the battle?

•

Do you know who the Black Prince

was?

•

Do you know what the Hundred Years

War was fought over?

•

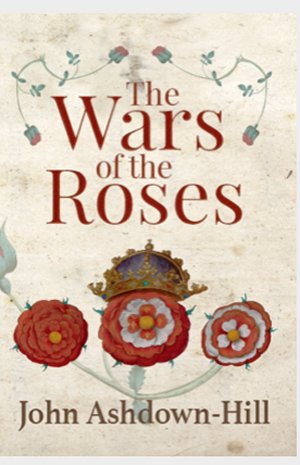

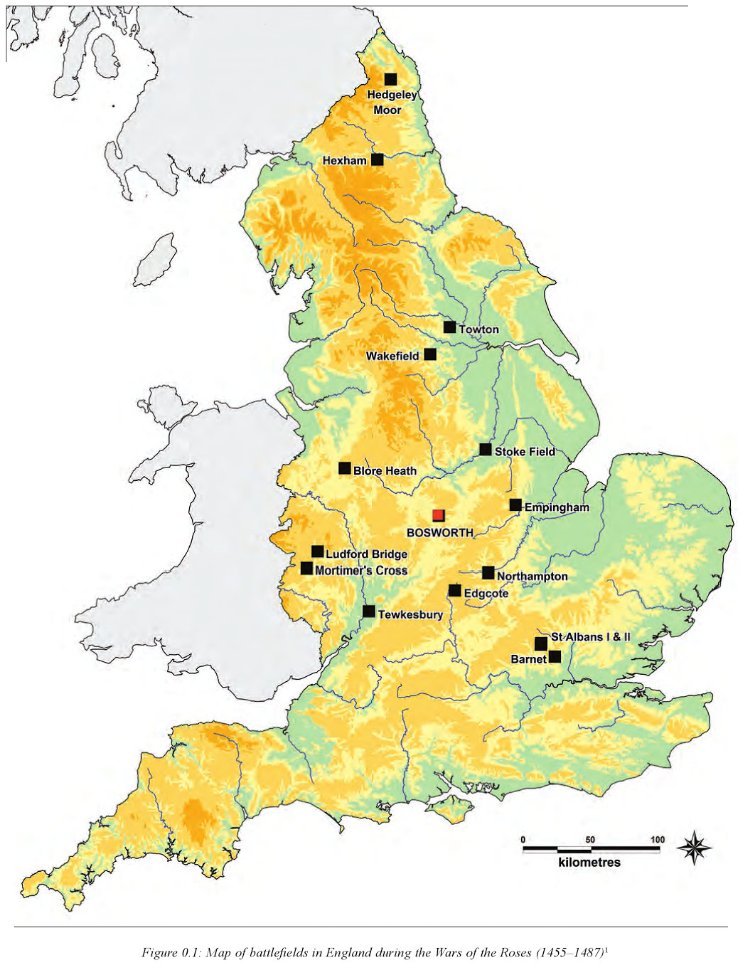

Do you know what the War of

the Roses was about?

•

Who spoke 'A horse, a

horse, my kingdom for a horse?'

•

Why is the date 1066

important?

•

What English monarch

murdered the closest claimant to the throne only to later

name their child to be succeed them?

•

Who was the most over-rated

King in English history?

•

What

was the name of the battle that ended the War of the

Roses?

Are you curious to know the answers?

If so, read on!

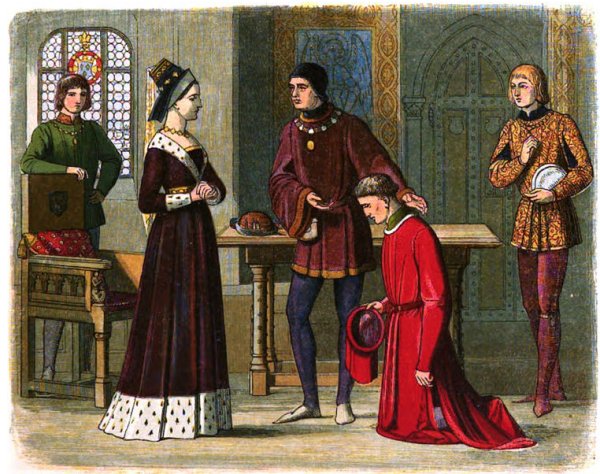

William the Conqueror and the

1066 Battle of Hastings

One of the reasons English

history is so fascinating is that there was always so much

drama surrounding the King. There were certain periods when

there was no clear successor to the throne. Two, three,

maybe even four people might have a legitimate claim to the

throne. Consequently there were plots, rebellions and

assassination attempts galore. There was always someone new

scheming to get rid of the current King and put someone

else on the throne.

the Battle

of Hastings was a perfect example

of the chaos that ensued every time an English King or Queen

died. The English loved war so much that transitions were

basically an open invitation to renewed bloodshed. Sort of

like America today... just kidding.

So what was the Battle

of Hastings all about?

King Edward the Confessor

was childless. His death in January 1066 set up a

succession struggle between several claimants to his throne.

Harold was crowned king shortly after Edward's death, but

faced multiple threats. First came Tostig, his own brother

who had been exiled. Tostig persuaded Norwegian King Harald

Hardrada to join him in the fight. There were two battles

in September 1066. Tostig and Hardrada won the first round,

but Harold won the rematch, killing both Tostig and Hardrada

in the process.

| |

|

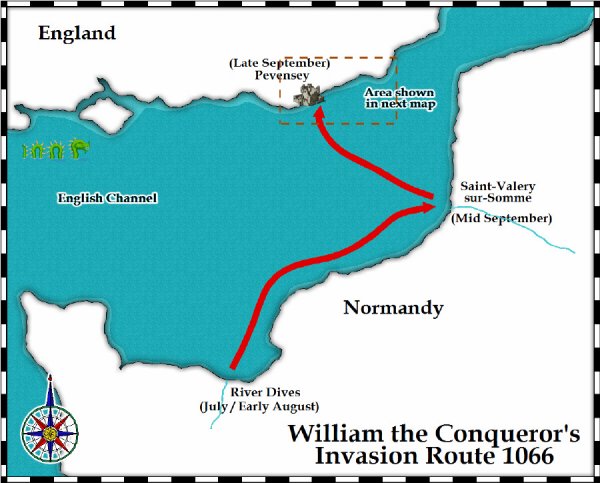

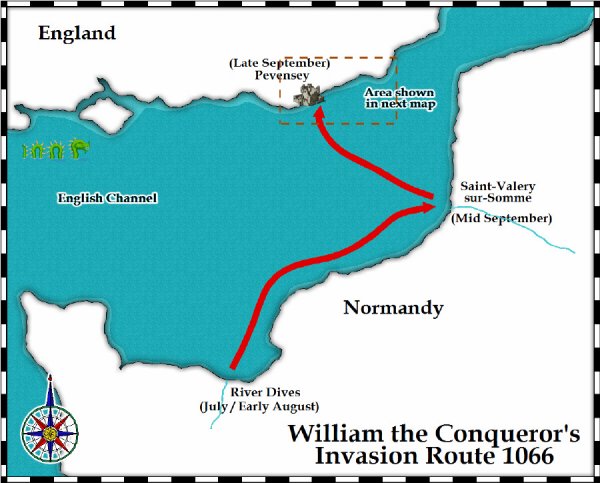

Now Harold had to face

William of Normandy. Normandy, of course, is where D-Day

took place in 1944. Normandy lies right across the English

Channel 100 miles to the south of England.

William wanted to be the

next King of England. William claimed that both Edward and

Harold had promised him the throne, but English supporters

of Harold challenged this. Basically, William had no real

claim to the throne, but that didn't matter. As always, 'Might

makes Right.'

While William was building ships

in Normandy, he also

assembled an invasion force. The

fleet sailed 60 miles

from the mouth of

France's Somme River in October 1066 and

landed on the English coast near Hastings, a town

50 miles southeast of London.

King Harold of England met William's

army just north of the coastal town of Hastings.

The two sides were evenly

matched. Consequently the battle lasted all day from

morning to sunset.

Early efforts of William's invaders to

break the English battle lines had little effect, so the

Normans tried a trick. They pretended to flee in panic and

led their pursuers into a trap.

Harold was one of the

victims. Legend says he was shot in

the eye with an arrow. His death near the end of the battle led to the

retreat and subsequent defeat of his army.

|

|

| |

|

A little known fact is that

Harold's defeat at Hastings was attributed to his appalling

lack of Archers. Makes perfect sense to me.

Everybody knows how important Archers

are.

After a few cleanup

skirmishes, William was crowned as the

English king on Christmas Day

1066. And there you have it... a Frenchman sat on the

English throne. The world had turned upside down.

William spent his entire life dealing

with the shame of being born a bastard. Even to his

death, there were whispers about his ignoble birth.

Rumor has it that even his eventual wife snubbed him over

this issue.

When William

asked for the hand of Matilda of Flanders, a granddaughter

of France’s King Robert II, she demurred

due to his illegitimacy.

According to legend, the snubbed Duke

tackled Matilda in the street, pulling her off her horse by

her long braids. In any event, Matilda

consented to marry him. Matilda

would go to bear her Conquering husband 10 children.

Maybe there is something to be said for the Tarzan approach.

| |

|

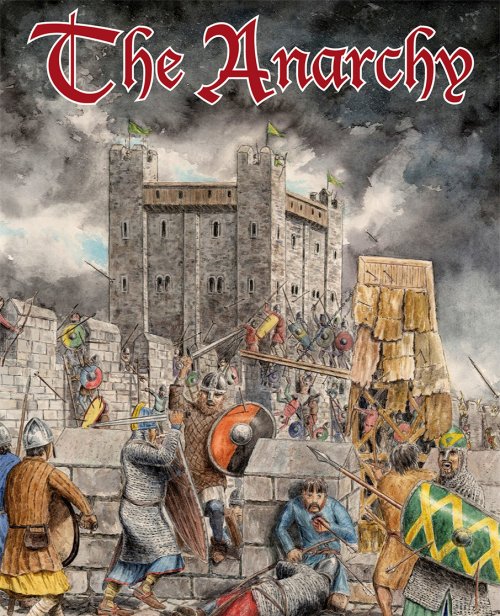

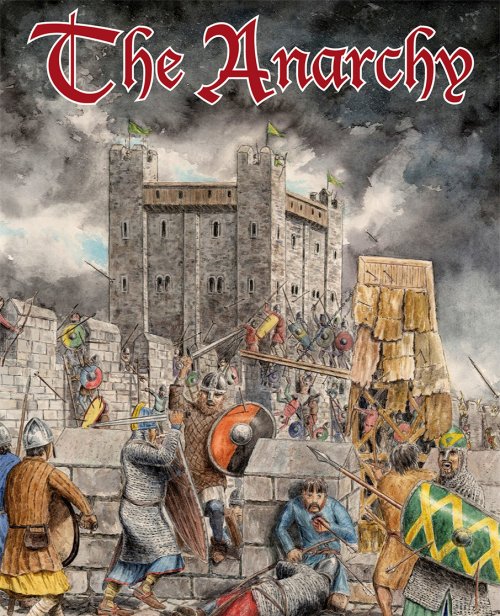

The Anarchy,

1135-1154

|

| |

|

The Anarchy was

a lawless time in England more or less like

America's Wild West. No one was really in

charge. The problem began problem started 70

years earlier when William the Conqueror, a

Frenchman of sorts (Viking bloodline, birth on

French soil), became King of England following the

Norman Conquest in 1066.

The repercussions were

profound as the invasion created an Anglo-Norman

elite, i.e. French barons whose main interest was in

France, but used their money and power to obtain

territory in England. In other words, England

became something of a French colony. These

barons now had estates and holdings in France as

well as in England.

To understand medieval France

and England, realize that 'Kings' in both

countries had only limited power. The barons

all had smaller Kingdoms of their own complete with

armies and castles. Sometimes they obeyed the

King, sometimes they didn't.

The most powerful English

barons typically lived back in France and visited

England from time to time. France itself was a

loose collection of counties and smaller political

units that were under only the minimal control of

the French king. In other words, England was

very disorganized and France wasn't really all that

much better.

Therefore, the barons ran wild.

Like little piggies, these barons wanted to rule

over as much land as possible no matter what the

cost. The easiest way to get land was to pick

a fight.

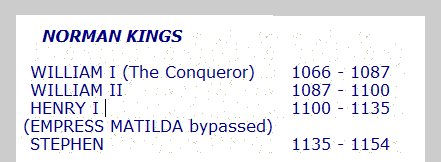

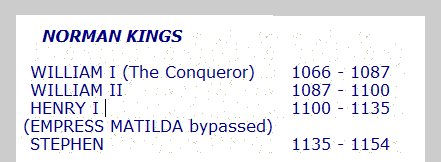

William II and

Henry I were the sons of William the

Conqueror who took over after his death. They

were called 'Kings', but really they were

more like the biggest baron of all. They

called the shots, but rebellion was always a

problem. The Anarchy began

when Henry I died suddenly.

|

|

| |

Geoffrey

Plantagenet and Empress Matilda

|

| |

|

|

The story of The Anarchy

begins with Empress Matilda.

One of real problems with

deciphering English history is that English Kings

were unimaginative when naming their heirs.

There were eight Henrys. There were eleven

Edwards. Henry

and Edward and Edward and Henry. On and on. Good grief, there

were more Edwards and Henrys than there are Star Wars episodes. If it wasn't for

Roman numerals, I don't know what the English would do.

Even the women got in the act.

William the Conqueror had four Matildas... his wife Matilda

of Flanders, his daughter Waltzing Matilda, his

daughter-in-law Matilda of Scotland, and his granddaughter

Empress Matilda.

|

| |

|

Here is the funny thing. For a

long time there, I

thought I was reading about the same woman. After all,

how many Matildas can there be in history? Then I got

suspicious when the stories didn't make any sense. It took me

20 minutes of

cross-checking to suddenly realize there were four of them!

Empress Matilda's father was Henry I,

the youngest son of William the Conqueror. Henry I

suffered a terrible misfortune when his two sons drowned.

This took place when the White Ship sank on its way

from France back to England.

Stripped of his two male heirs, Henry I broke tradition and

specifically named his daughter Empress Matilda to be his successor.

So why was Matilda an Empress?

Matilda had once been married to a

German king who was named ruler of the Holy Roman Empire.

This made her the Empress of the Holy Roman

Empire, an institution in continental Europe under the

jurisdiction of the Catholic Pope. However, her husband's death had sent Matilda back to

England as a widow at 23.

Matilda was eventually

forced to marry Geoffrey Plantagenet, the Count of Anjou,

a wealthy French landowner. Matilda was very unhappy

about this. For

starters, she was 25 and Geoffrey was only 13. She had

once been an Empress, now she was marrying down to a mere

Count. Boo hoo hoo.

Matilda's father pointed out that this

marriage would combine two of the most powerful Anglo-Franco

families ... the Normans and the Plantagenets. Henry I

chose Geoffrey to sire his grandchildren because his lands

were strategically placed on the Norman frontiers and he

required the support of Geoffrey's father, his erstwhile

enemy, Fulk of Anjou. He accordingly forced his highly

reluctant daughter to marry the fifteen year old Geoffrey.

Matilda wasn't happy about it, but she

got with the

program and married Geoffrey. The pair disliked each

other from the outset of their union and neither was of a

nature to pretend otherwise and so the scene was set for an

extremely stormy marriage. They were, however, finally

prevailed upon by the formidable Henry I to do their duty

and produce an heir to England. They had three sons, Henry

was the eldest of these and always the favourite of his

adoring mother.

Eight years after her 1127 marriage to

Geoffrey, things got interesting. Matilda's

father Henry fell ill and died suddenly in 1135. This meant Matilda

was now the heir to the English throne and the ruler of

Normandy. Unfortunately, the English barons who had vowed to support the accession of Matilda to

the throne reneged. Stephen of Blois was a well-known,

popular figure among the barons of Anglo-Norman society.

He also had the advantage of being right across the English

Channel when news of the king's death was spread.

Meanwhile Matilda was stuck in the center of France and

unable to press her case in person.

Stephen was attractive to the English

barons for two reasons. One, he was not only the

direct grandson of Henry I, the king had always treated

Stephen as a favorite. Second, these men were not too

keen on putting a woman on the throne. The English Council acted

like they were still stuck in the Dark Ages and denied Matilda the crown. They

stepped aside and allowed Stephen, Matilda's cousin, to

seize the throne instead. Matilda had been cheated of

her crown.

Matilda was royally

irritated. It did not help that

Matilda was haughty, disagreeable and

ill-tempered by nature. So naturally Matilda went to war

against Stephen.

That's what everyone did back in those days. It didn't

do her much good. She won a few battles, lost a few

battles, then got frustrated and gave up. The

Anarchy was not going in her favor

at all. By the late 1140s the active

phase of the civil war was over. In a huff,

she returned to France and fumed.

Stalemate.

Matilda was determined to have the last laugh.

As it turned out, Matilda had a strapping son at home.

Henry Plantagenet was her son by Geoffrey

Plantagenet. Born in 1133,

he was three years old when his mother was

cheated of her inheritance. By age

nine, Matilda had Henry fighting at her side. However,

they just couldn't seem to break though.

Then someone new appeared. Matilda

would receive help from an unexpected source... a woman her

husband had just had a fling with.

|

|

|

|

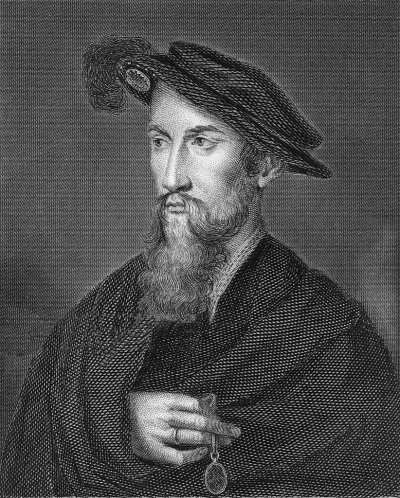

Geoffrey Plantagenet

of Anjou

|

| |

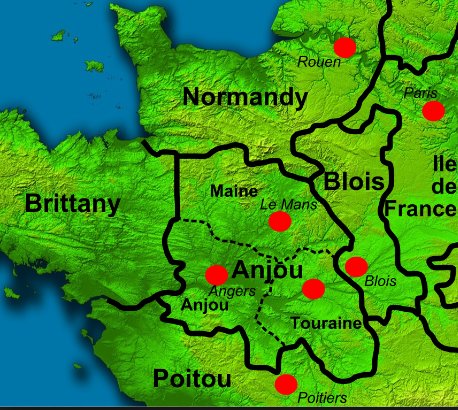

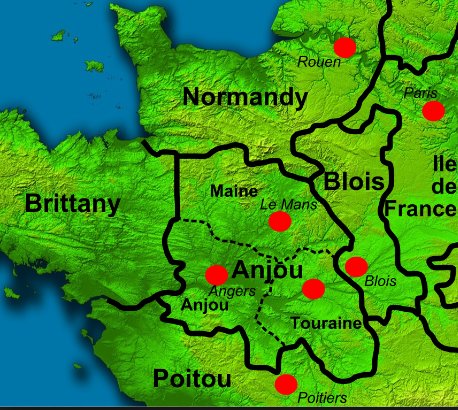

Geoffrey Plantagenet

was a powerful man who ruled over his ancestral domain of Anjou.

The House of Plantagenet had extensive land holdings

in France.

Through her birthright to

William the Conqueror, Matilda also had

extensive claims in Normandy which was neighbor

to

Anjou. Count Geoffrey had little

interest in England, but he was very

interested in Normandy. Geoffrey

initiated a war to obtain the duchy of

Normandy, but it was slow-going.

It became clear to Geoffrey that Stephen

would need to be challenged in England in

order to bring his own conflict to a

successful conclusion. So in 1139

Matilda invaded England. From the age of

nine, their son Henry was repeatedly sent to

England to be the male figurehead of the

campaigns. This made sense since Henry

would become king if England could be

conquered.

While his wife Matilda was off in England

fighting Stephen, Geoffrey invaded Normandy

on behalf of his wife. The Norman

barons initially opposed him, not through

loyalty to King Stephen, who had only

visited Normandy on but one occasion, but

from hatred of their traditional enemy,

Anjou.

While Geoffrey was attempting to conquer

Normandy, he was also forced to put down

three rebellions in Anjou created by his

younger brother. The threat of

rebellion not only slowed Geoffrey's

conquest of Normandy, it is the main reason

he could not intervene in England to aid his

wife.

|

|

|

| |

Eleanor of Aquitaine

|

| |

|

Eleanor

of Aquitaine

(1122-1204) appeared in the middle of Matilda's

fight in England and Geoffrey's fight in Normandy

and Anjou. Life would never be the same.

Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, is a

determined woman who plots and schemes an astonishing

path between two equally powerful men in twelfth century

Europe.

This is a woman who can

maneuver and manipulate to

safeguard her own lands as effectively as any

power-grasping lord. Eleanor is single-minded in her

struggle to keep her inheritance intact, leading her to

reject one husband and take another who will fulfill her

desires.

Eleanor intends to reign as Queen and is

prepared to bring scandal down upon herself in pursuit

of her ultimate prize. Hers is a story of power,

political intrigue, passion and love.

This restless queen will sweep across the 12th

century, changing the face of Europe.

Eleanor's story is fascinating. She was the

daughter and heir of the imperious William X, Duke

of Aquitaine and Count of Poitiers. Her father

possessed the largest domains in northwest Europe,

indeed larger than those held by the king of France,

Louis VI from the House of Capet. When her father

died in 1137, Eleanor, 15, came into her

inheritance. Complying with the dictates of a

territorial agreement, she married Louis VII, heir

to the French throne. Barely a month after the

wedding, King Louis VI died, thrusting Eleanor’s

16-year-old groom to the throne of France.

Eleanor found court life as queen of France

stultifying. Her timid, sweet-tempered and devout

husband exasperated her. Formed during her

childhood at the court in Poitiers where she was

rarely disciplined and always admired, her strong

ego impelled Eleanor to create a lofty royal vision

for herself, one that did not encompass the

subordinate role as queen of France.

|

|

|

|

After a

decade of marriage to Louis, she was as beautiful

and capricious as ever, but even more headstrong and

domineering toward her husband. From 1147 to

1149 Eleanor insisted on accompanying him during the

Second Crusade. Apparently the adventure

carried a rude awakening... Crusading was no fun.

According to Simon Schama, “Eleanor was dismayed to

discover that crusading was an arduous, pious

business. She quickly developed an unhealthily warm

relationship with her uncle, the slightly impious

Raymond of Poitiers.” While her husband fought

battles in the Holy Land, Eleanor spent her time in

arms of Raymond in complete comfort for the duration

of the crusade. This understandably caused an

estrangement.

Though at one time Louis had adored his wife, after

15 years of marriage he was willing to let her go

for the sake of the Capetian royal line.

Eleanor had not borne him a son and heir, only two

daughters. Eleanor, on cue, illuminated her

predicament, explaining that her husband’s

infrequent visits to her bed accounted for the

fruitlessness of their union. In the end, the

marriage was annulled on the convenient grounds of

consanguinity: Eleanor and Louis were too closely

related for the church to tolerate.

|

|

|

|

As Duchess of Aquitaine,

a massive duchy in

southwestern France, Eleanor was the most eligible bride in Europe.

Men came calling.

Following the dissolution of her marriage,

Eleanor regained possession of Aquitaine and

Poitou. This wealth combined with her

loveliness attracted suitors well before the

annulment was final, one of whom was Henry

of Anjou (a domain bordering Poitou), soon

to be known as Plantagenet.

One of the men who came calling was Geoffrey

of Anjou. Most historians agree that

Eleanor and Geoffrey were sexually intimate.

Historian Schama notes, “It was rumored that

Geoffrey of Anjou had personally verified

Eleanor’s appetite for passion before

recommending her to his son.”

Now Henry, Geoffrey's son, came calling as

well. The 30-year-old Eleanor and

18-year-old Henry felt passionately

attracted to one another. Henry’s

unsurpassed physical courage and keen

political acumen resonated with Eleanor’s

ambition for power. Another attractive

feature was that Henry, now the Duke of

Normandy and Anjou, could very likely become

the next King of England.

Asked some years before to assess Henry’s

chances of success of becoming King of

England, St Bernard of Clairvaux said of

Henry that ‘from the Devil he came, and

to the Devil he will surely go’.

It did not matter that Henry was reported to

be the spawn of Devil. That suited

Eleanor's tastes just fine. Not

exactly a shrinking violet herself, Eleanor

chose to be the Devil's consort.

Eight weeks after her annulment, Eleanor

married Henry in 1152. Instantly the marriage doubled

the land holdings of Europe's new power

couple.

Over in Paris, Eleanor's former husband

Louis VII flipped out. Louis not only

considered the marriage an insult to him, he

was also infuriated because Henry now

possessed a much larger proportion of France

than Louis did himself.

|

|

|

|

Henry Plantagenet

becomes King

|

| |

|

|

Strengthened by his

1152 marriage to Eleanor, Henry Plantagenet

wasted no time going back after Stephen.

Henry's mother Matilda was still seething

over her cousin Stephen's theft of her

crown. Based on Matilda's strong claim

to the English throne, Henry had a powerful

claim of his own. Indeed, his

grandfather Henry I had once called him the

future king of England.

Under the reign of the

usurper Stephen, for the previous twenty

years the Anglo-Norman realm had suffered

through a civil war fought out between the

adherents of Stephen and those of Henry’s

mother, the Empress Matilda. In this

time, lawlessness prevailed. It was

every man for himself. Northern

England had been seized by the Scots. The

Welsh had made substantial advances in the

West. England itself had been

partitioned between warring baronial

factions, each with its own competing and

still unresolved claims to land, castles and

local power.

The fighting between

Henry and Stephen continued, but no one

could

get the upper hand for long. Finally, the two armies

met at Wallingford to begin fighting the

battle to end all battles. Taking note

that neither side had an advantage and that

lots of men, barons included, were about to

die, cooler heads prevailed. The

Anarchy had been going on for 20

years. Enough was enough. Since

neither side's barons were keen to fight

another pitched battle, the barons had an idea... why not

ask the clergy to broker a peace?

So, much to the

annoyance of Henry and Stephen, the battle

was postponed. Stephen began to

examine a negotiated peace, a process

hastened by the sudden death of Eustace, his

son and heir. In the Treaty of

Winchester, Stephen recognized Henry as his

heir in exchange for peace. Stephen

conveniently died the following year in

1954. Henry was King; Matilda was

vindicated.

|

|

| |

|

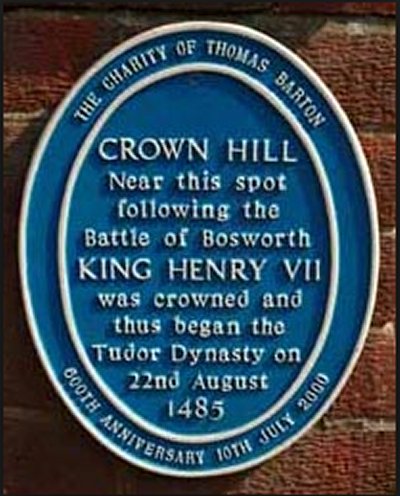

Henry II and

the Plantagenet Dynasty

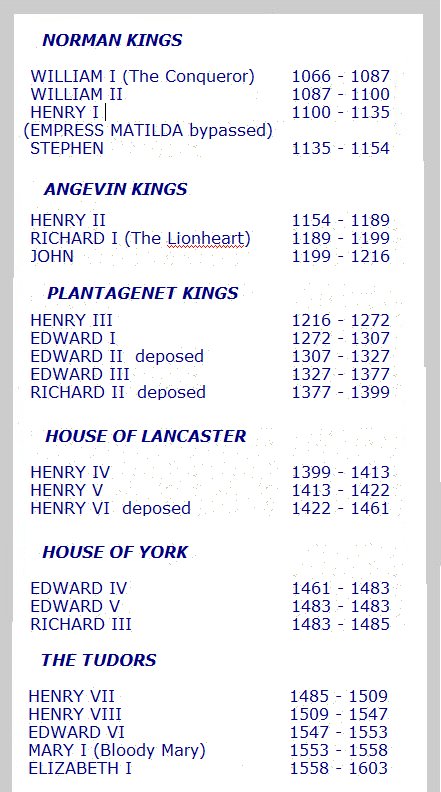

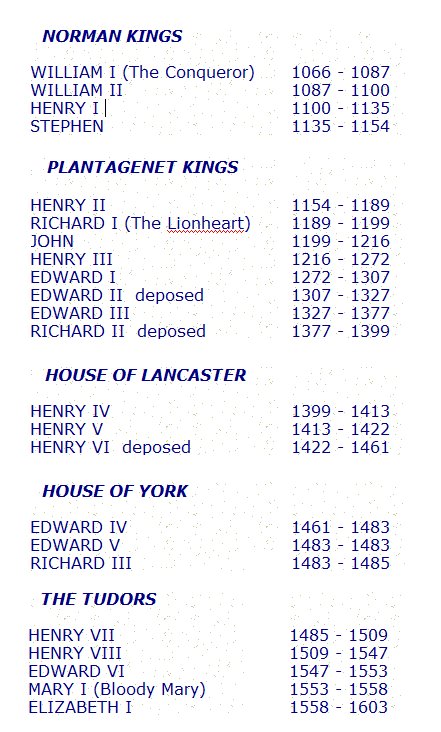

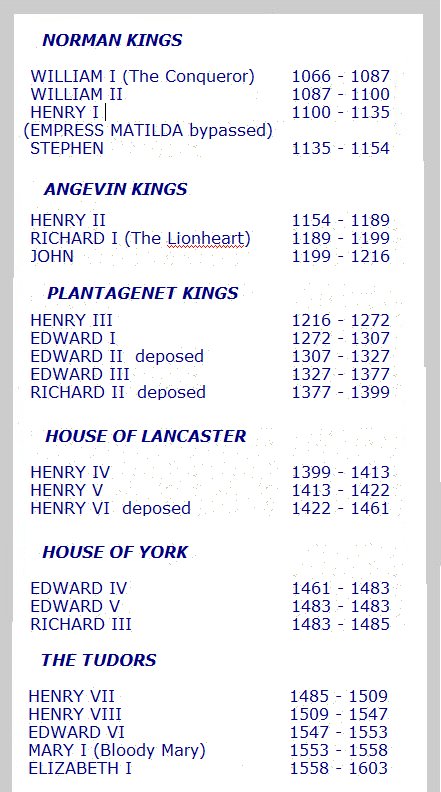

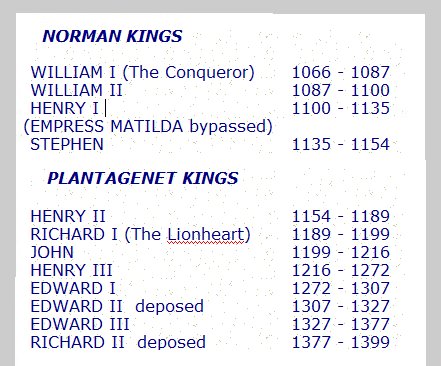

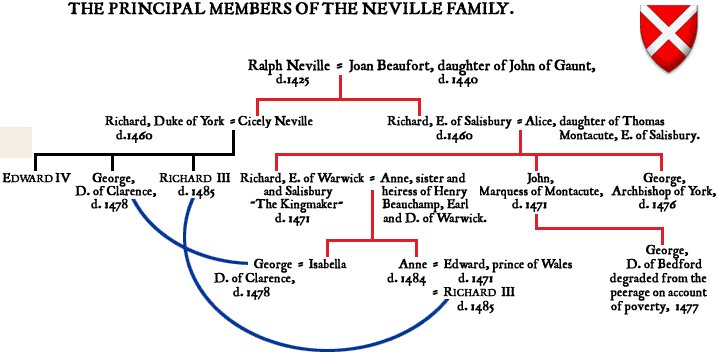

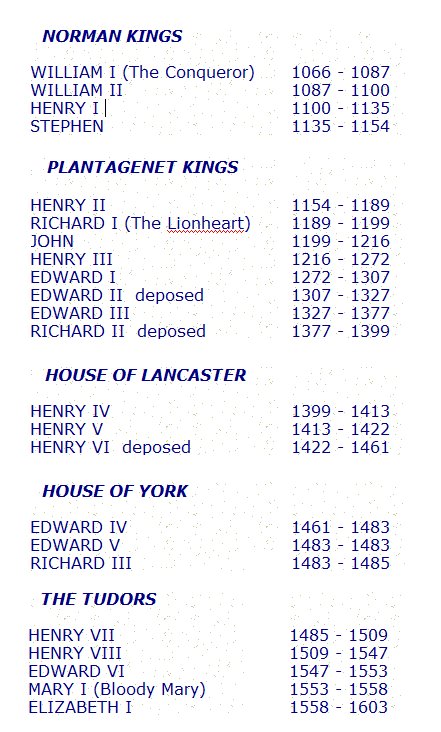

Ruling from 1154-1189,

King Henry II would emerge as one of

England’s, indeed as one of Europe’s,

greatest kings. The Plantagenet

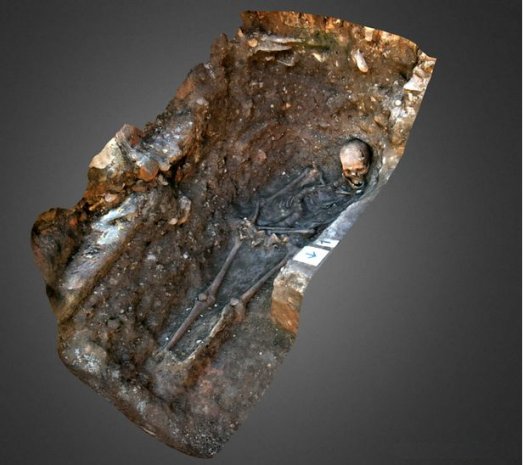

dynasty founded by Henry II

would hold the English throne

for three and a half centuries (1154-1485), starting

with the 1154 accession of Henry II and

lasting until

1485 when Richard III died.

King Henry III was the

grandson of Henry II through King John.

Henry III had two sons... Edward I and

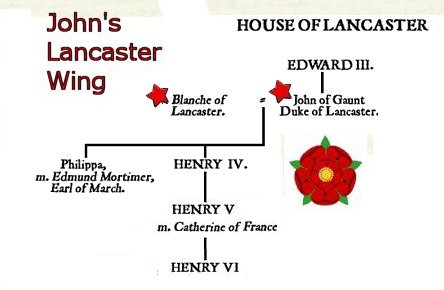

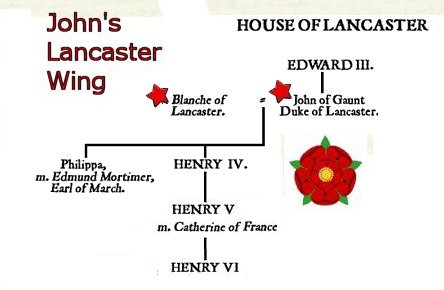

Edmund Crouchback. ANGEVIN KINGS

The House of

Lancaster was a branch of the royal

House of Plantagenet. The first house was

created when Henry III created the Earldom

of Lancaster—from which the house was

named—for his second son Edmund Crouchback

in 1267.

Over time, the House

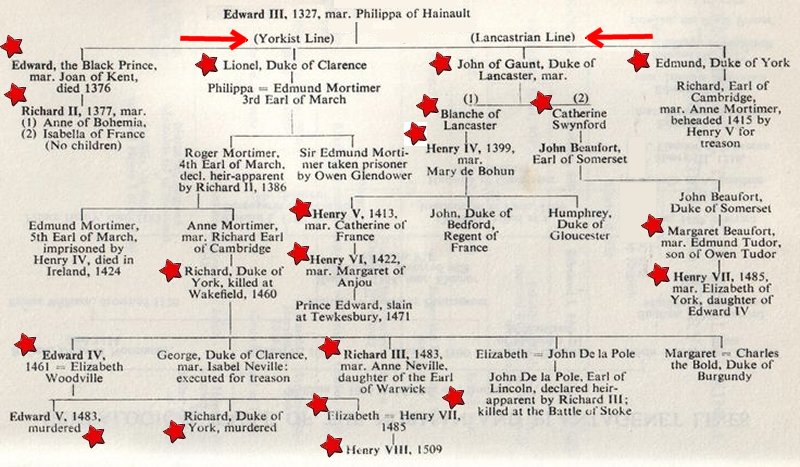

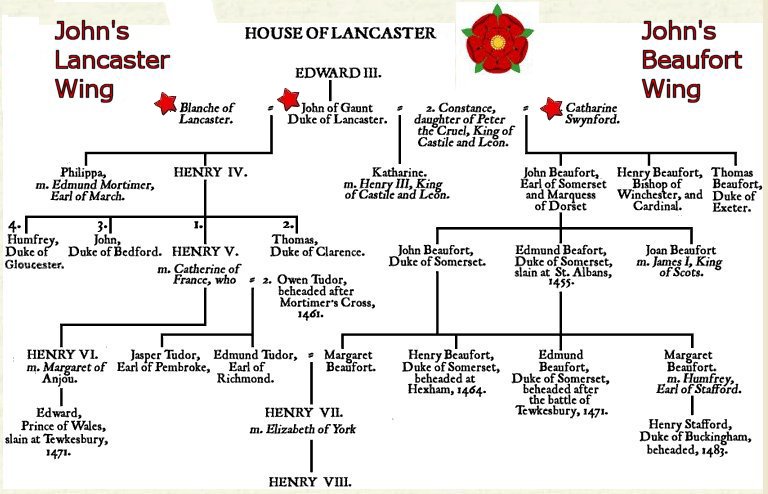

of Lancaster subdivided into two wings.

The 1359 marriage of John of Gaunt from one

wing of the House of Lancaster to Blanche

from the other wing of the House Lancaster

reunited the two wings. Starting in

1399, the House of Lancaster would give

birth to three future kings.

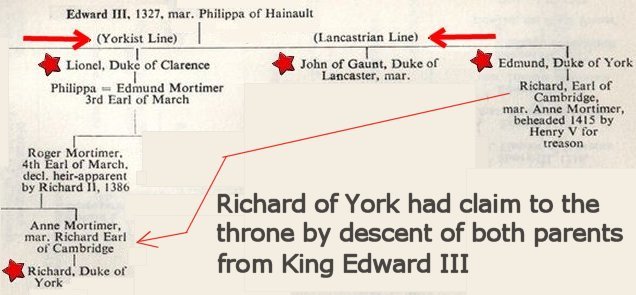

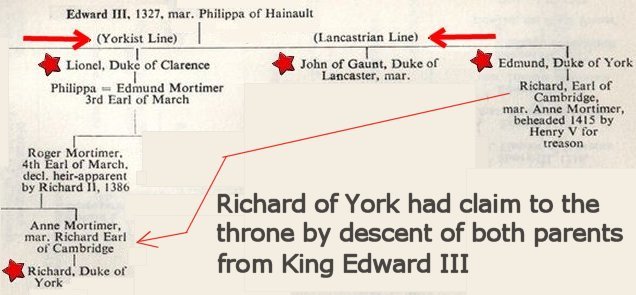

Meanwhile, King Edward

III was the grandson of King Edward I.

As we shall see, Edward III was a pivotal

figure in English history.

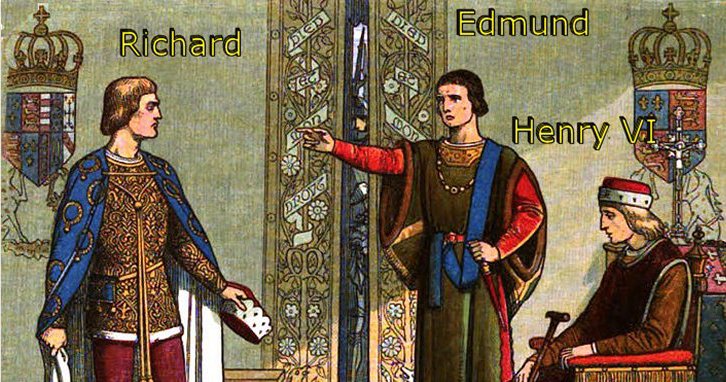

•

Edward III named John

of Gaunt, one of his sons, the Duke of

Lancaster.

•

Edward III named

Edmund, another other son, the Duke

of York.

•

Edward III had yet

another son, Lionel, whose descendent

Richard, Duke of York, would

play a key role in English history.

Are you following all

this? If you haven't already guessed, English history

is very complicated. So let me simplify things

a bit.

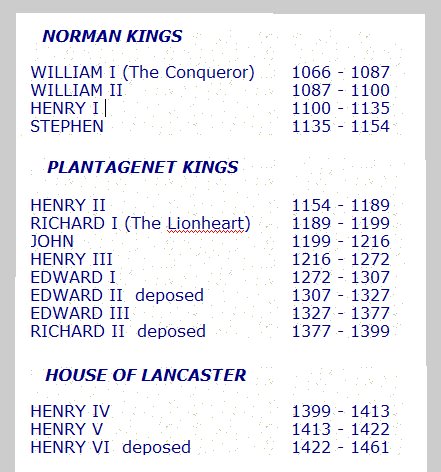

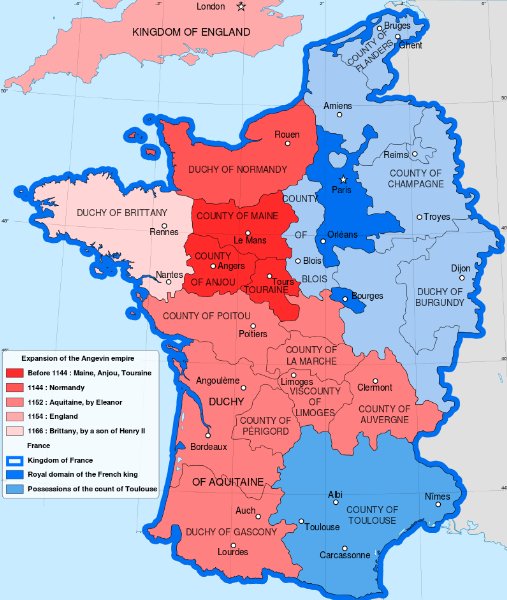

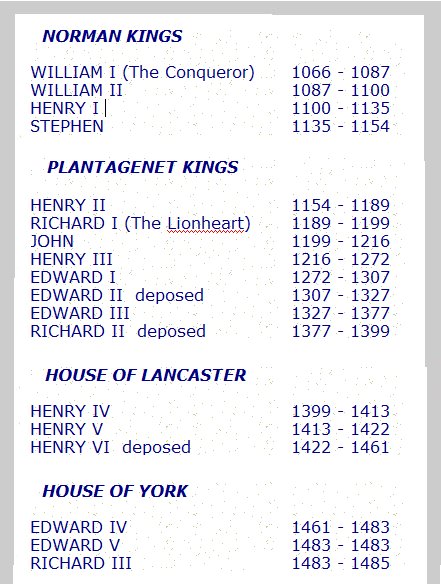

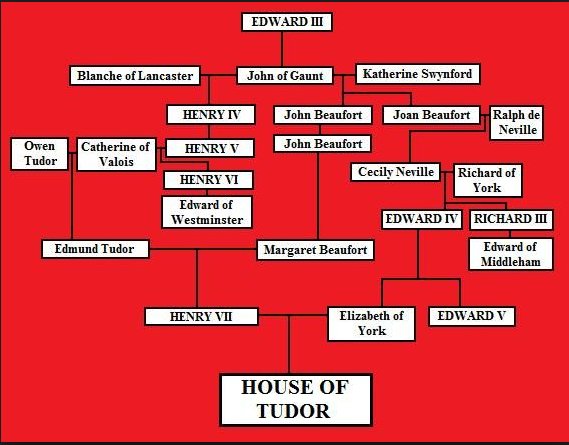

The bottom line is

that the Angevin kings... Henry II, Richard

I, John I... were Plantagenets. The

Plantagenet kings... Henry III, Edward I,

Edward II, Edward III, and Richard II...

were Plantagenet kings. The Lancaster

kings... Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI...

were Plantagenet kings. The York

kings... Edward IV, Edward V, Richard III...

were Plantagenet kings. The Tudor

kings and Queen Elizabeth were Plantagenets

as well.

It all started with

Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine.

|

|

|

| |

|

Henry II and the

Angevin Empire

|

| |

|

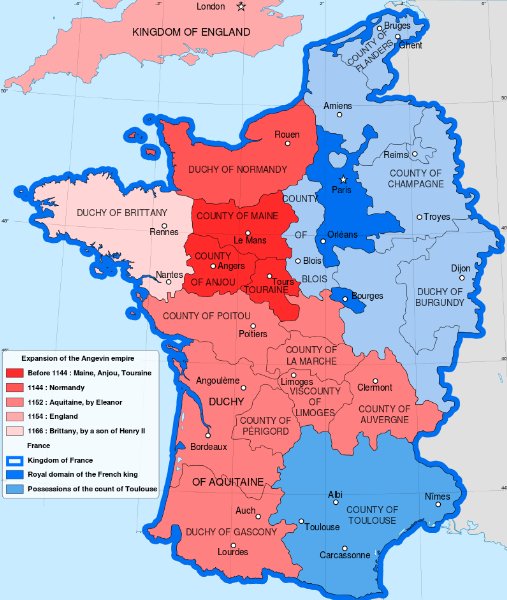

The term

'Angevin' is a reference to the duchy of 'Anjou',

birthplace of Henry II.

Thanks

to a perfect storm of good luck, Henry came to rule

over the most extensive collection of lands that had

ever been gathered together under an English king.

•

From his father, Geoffrey,

Henry succeeded to rule over Anjou, Maine and the

Touraine: the counties of the Loire valley that had

previously blocked Anglo-Norman ambitions in the

South.

•

From his mother, Matilda,

daughter and sole surviving legitimate child of the

last Anglo-Norman King, Henry inherited his claim to

rule as king in England and as duke in Normandy.

•

From his wife Eleanor, Henry

found himself in possession of a vast estate in

southwestern France, stretching from the Loire

southwards through Poitou and Gascony to the

frontiers of Spain.

This was

an empire in all but name. Henry's lands

stretched from the Cheviots to the Pyrenees, and

from Dublin in the west to the frontiers of Flanders

and Burgundy in the east. And this all just

for starters. Henry would acquire more lands

throughout his reign.

|

|

| |

|

Henry II of Anjou was more French than he was

English. His native tongue was French. A

brilliant soldier, he extended his French lands

until he ruled most of France. With territory

stretching from sea to shining sea, by the late

1170s, Henry ruled an estate that eclipsed anything

that had been seen in France since the time of

Charlemagne and in Britain since the fall of Rome.

In its cultural and political sophistication,

Henry’s dominion badly outshone the Capetian kings

of France. Louise VII, struggling to maintain his

rule over the immediate vicinity of Paris, could

only look on in astonished but for the most part

impotent amazement. Henry had set England on a path

to becoming one of the world’s most dominant

nations.

So was Henry II a happy guy?

One can only wonder. Henry would prove to be a very

controversial king. Although he had succeeded

in wresting control of England from the barons who

had gotten too big for their britches, he quarreled

with everyone under sun including his wife, his

sons, the barons, Thomas Becket, and King Louis of

France.

Henry quarreled a lot his

wife. By temperament Eleanor was just as fiery

as Henry, and as determined to stake her own claims

to rule. Despite their

turbulent marriage, they did find the time to produce

eight children, mostly notably King Richard I the

Lionhearted, the son who would succeed his father.

Henry had one very bad habit.

He did not like to share his lands. He did not

share his inheritance with his brothers and he had

trouble sharing his estates with his sons.

Naturally his sons turned rebellious. And when

they did, his wife took their side. As a

result, Henry’s domestic life was far from tranquil.

Henry lost his temper with Eleanor and had her

imprisoned under house arrest for sixteen years.

She would not be freed until his death in 1189.

Henry is remembered for his

quarrel with Archbishop Thomas Becket. After

Becket's subsequent murder in Canterbury Cathedral

on 29th December 1170, his sons turned against him,

even his favorite son John. Henry II spent all

his later years fighting wars with his own sons.

Henry II died a bitter man, hated by practically

every noble on either side of the English Channel.

|

| |

The Legend of Eleanor

Lives On

|

| |

Eleanor was Queen of England

for 44 years (1154–1189).

Over the first

thirteen years, she bore Henry eight children: five

sons, three of whom would become kings; and three

daughters.

However,

over time Henry and Eleanor

became estranged. Henry imprisoned her in

1173 for supporting her son Henry's revolt against

her husband. In

1173, Eleanor’s son “Young Henry”

fled to France. He was

apparently plotting

against his father to

seize the English throne.

Eleanor

was rumored to be actively supporting her

son’s plans against her estranged husband,.

She was arrested and imprisoned for treason.

Once apprehended, she spent the next 16 years

shuttling between various castles and

strongholds in England. She

was constantly suspected of agitating against

her husband’s interests.

Some even say she played a role in the death

of Rosamund, Henry's

favorite mistress.

Eleanor was not released until 6 July 1189,

when Henry died and their son ascended the English

throne as Richard I.

|

|

| |

After

Henry's death, Eleanor became a babysitter of sorts

for her son Richard who went off to play in the

Crusades.. Eleanor ruled the country as Regent

in Richard’s name while he led the Third Crusade.

Eleanor

lived to the remarkable age of 82. She was

able to see her youngest son John crowned king after

Richard’s death and was employed by John as an envoy

to France. Eleanor would eventually retire as

a nun to the abbey at Fontevraud, where she was

buried upon her death in 1204.

Endowed

with intelligence, creative energy and a remarkably

long life, Eleanor of Aquitaine played a major role

in the 12th century. This was an impressive

achievement given that medieval women were

considered nothing more than chattel. Her

intelligence and enterprise served her well in the

chaos of the time as she negotiated the unrelenting

hostilities between Plantagenets and Capets,

crusades and struggle between church and state.

In a ruthless era, Eleanor stood tall.

Too bad

her sons didn't inherit her cunning. It had to

be a terrible shame to see her sons, Richard the

Lionheart and King John turn on their father and

then later against each other. Together they

brought the Angevin dynasty to the edge of

annihilation.

|

| |

|

Who is the

Most

Over-Rated King in English History?

Let's start

this

question by playing the Name Game.

My full name is 'Richard

James Archer.' English names hang like ornaments

throughout my family tree.

'James'

is my father's name. James is the most common male first

name in all of Britain. James is a royal name associated

with the Scottish house of Stewart. James I of Scotland was

the man who succeed Queen Elizabeth I in 1603. King James

was a patron of the arts as well as a talented ruler.

'Mary'

is my mother's name. Mary is the most common female first

name in all of Britain. The name Mary is sprinkled

throughout English and Scottish history. Bloody Mary, Mary

Queen of Scots, William and Mary, and of course the beloved

Queen Mary III. Queen Mary and her husband King George V

ruled during World War II. Queen Mary was the mother of

the current Queen Elizabeth.

'William'

is the fifth most common male English name. William was the

name of my grandfather and one of my uncles. William is

everywhere in English history. For example, William the

Conqueror. Remember him? William changed the history of

the world thanks to his conquest of England in 1066 at

the Battle of Hastings.

'Richard'

is a name of Germanic origin, derived from 'ROC' which means

'power' and 'HARD' which means 'hardy'.

That's me all right, Rock Hard Richard!

So let's

see how the most famous Rock Hard English King of them all

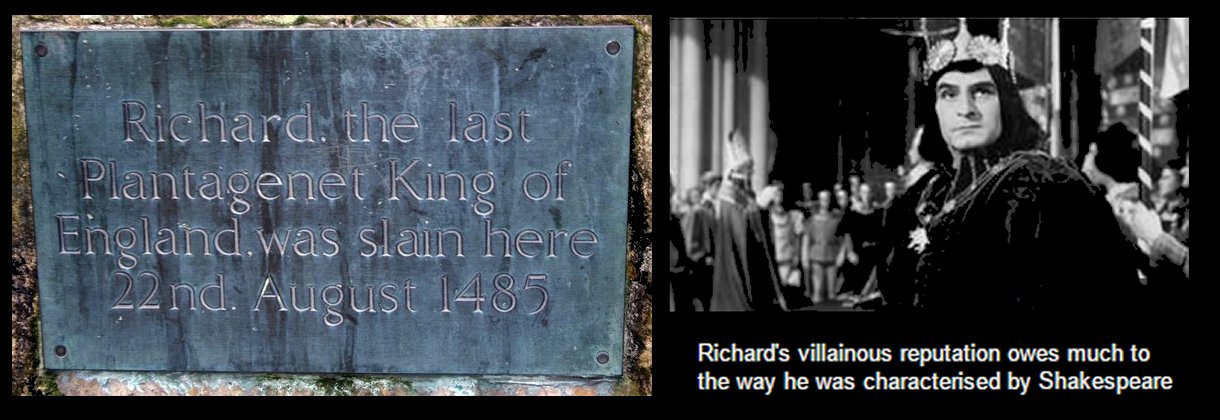

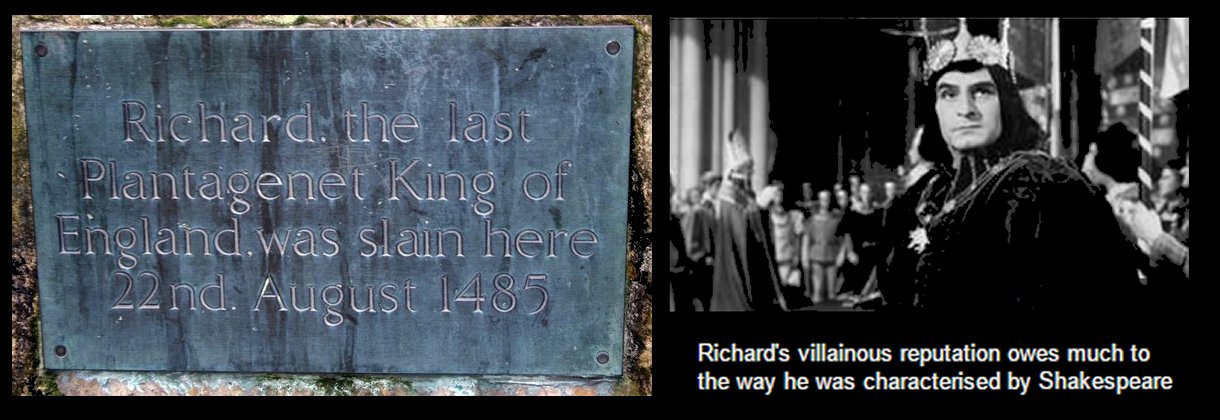

fared. 'Richard'

has been the name of four

different English Kings, two of whom were rotten,

one of whom became Shakespeare's greatest villain and the

fourth is considered the most overrated

King in English history. By

the way, I was named for the over-rated

one.

| |

|

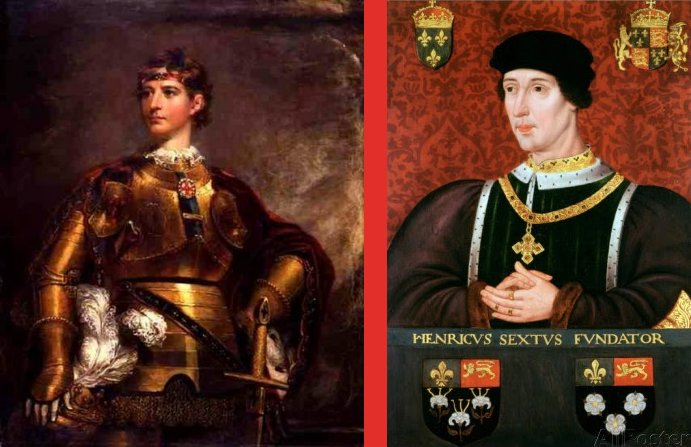

King Richard the Lionheart

|

| |

|

And that brings us to 'Richard

I', better known as King Richard the Lionheart, the

most famous Crusader of all!

(Let us pause

for the

trumpets to blare!)

According to my mother, King

Richard the Lionheart was the man I was named for. I was

very proud to be named after the illustrious English King.

According to my father, our

surname 'Archer' descended from Robin Hood and his

Merry Men.

Gullible little critter that

I was, wow, here I was... part Richard the Lionhearted and

part Robin Hood!!

Alas, if only we could have stopped with

the Adventures of Robin Hood starring Errol

Flynn as Robin and Olivia de Havilland as Maid Marian.

That was defining movie of

my childhood. 3 Oscars! Much acclaim!

|

|

| |

|

|

In

the movie, Robin Hood

becomes my hero. He

is depicted

as a heroic outlaw folklore who, according to

legend, is a highly skilled archer and swordsman.

Traditionally dressed in Lincoln green, he is

portrayed as a champion of the

downtrodden, "robbing from the rich and giving to the poor"

with the help of his loyal band of Merry Men.

He

fights off the bad guys, keeping the Sheriff of Nottingham and evil

Prince John at bay while

noble Richard is away at the Crusades.

Then

Robin Hood comes to the rescue of King Richard when he

returns. There is a joke in

Hollywood that King Richard had an amusing

nickname... ‘Richard of the Last

Reel’. Film buffs love

to make fun of the fact that Richard appears

at the end of every Robin Hood film as the heroic,

and supposedly victorious, crusader monarch

returning to punish treacherous Prince John and the

wicked Sherriff of Nottingham.

Action! Adventure! Courage!

Chivalry! History!... well, not so much history.

To begin with, there are

strong rumors that Richard did not even speak

English. In his whole reign, he spent no more

than six months north of the Channel. For that

matter,

imagine my pain when I discovered Robin Hood... the

man who was the most famous Archer in

English history... may not

have actually existed.

The

subject of ballads, books and films, Robin Hood has

proven to be one of popular culture’s most enduring

folk heroes. Over the course of 700 years, the

outlaw from Nottinghamshire who robs from the rich

to give to the poor has emerged as one of the most

enduring folk heroes in popular culture.

But did a real

Robin Hood inspire these classic tales?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

What a shame it was I had to

grow up and learn the truth that the

greatest Archer of all time was probably a Hollywood

sham.

Robin

Hood, Fact or Fiction?

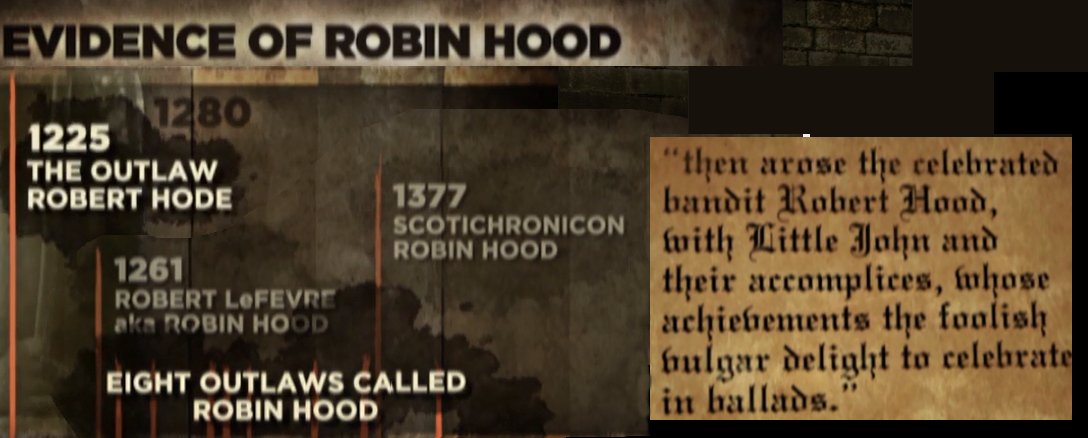

The History Channel suggests that Robin Hood

may have existed. In fact, research has turned

up mentions of eight different outlaws calling

themselves 'Robin Hood'. The problem is

that the first known mention took place in 1225.

'Richard of the Last Reel' died in 1189.

Whether Richard met the legendary

outlaw Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest, we do not

know, but it seems kind of

unlikely.

Personally I like the idea of

weaving legends together.

I think

this is a great idea. Davey Crockett can be

Abe Lincoln's best friend. Thomas

Jefferson can suggest improvements to Obamacare.

Vladimir Putin can

assassinate John F. Kennedy with a magic bullet

controlled by hackers. Donald Trump can grope

Pocahontas. Why let the truth get in the way

of a great yarn??

Alas, when I learned Robin

Hood was only a legend, I was fit to be tied. Half of my

gallant identity was gone. Well, no matter, I still had

Richard the Lionheart, brave Crusader, wonderful King. Yeah, well, then I

discovered that Richard the Lionheart was pretty much

useless as a King. During his ten years reign as King,

Richard spent at most six months of it in England. The rest

of the time he gallivanted across Europe and the Middle East

involved in the Crusades. Richard won a bunch of battles,

but he was unsuccessful in retaking Jerusalem from his

nemesis Saladin, the Muslim warlord.

Then Richard managed to get

captured in Austria on his return home. He spent nearly

three years of his reign in captivity until the ransom was

finally raised. Once he was free, Richard

returned for a couple of weeks, then left for France never even

bothered to set foot in England again.

Richard

spent his final years fighting battles to reclaim

territory in Normandy.

My loyalty to Richard was further

shaken when I discovered he was either gay or bisexual.

Despite being married, Richard did not have a child.

Nor did he bother to return to his wife following the

Crusades. In addition, there is a curious historical

quote involving King Philip II of France.

Richard

the Lionheart and Philip II of France “ate every day at

the same table and from the same dish, and at night their

beds did not separate them.” Uh oh. What could this

mean??

However, historian Dr. John

Gillingham discounted the idea that

Richard was gay.

"The idea wasn’t even mooted

until 1948 and it stems from an official record

announcing that, as a symbol of unity between the two

countries, the kings of France and England had slept the

night in the same bed. It was an accepted political act,

nothing sexual about it; just two politicians literally

getting into bed together, a bit like a modern-day photo

opportunity."

So what was the story on this

kidnapping?

I hate to say it, but Richard was not

the nicest guy. During the Crusades, Richard quarreled

constantly among the French, German and

English contingents. Irritated, they all went home,

leaving Richard to fight on alone. After a

year's stalemate, Richard made a truce with the famous

Saracen ruler Saladin and

decided to head home. However, there was one problem.

Towards the end of his Crusade adventure, Richard was stuck with over

three thousand Muslim prisoners. Tired of feeding them

and unable to ransom them, Richard had their throats slit.

Richard's bad karma soon caught up to

him. Bad weather drove him ashore near Venice. Now he

had to head home on foot. Having insulted and alienated most of his

Christian allies while on crusade against Saladin, Richard

was unable to return to his kingdom in broad daylight.

He was caught sneaking in

disguise through the territory of Leopold, Duke of Austria, one

of the many enemies he had made in the Holy Land.

Leopold handed Richard over to the German emperor Henry VI,

who ransomed him for the huge sum of 150,000 marks.

This was literally a King's Ransom.

The ransom asked was about 2 billion pounds in today’s

money. Its payment required 25 percent of each

Englishman’s income for a year.

Interestingly, while Richard's ransom

nearly bankrupted his country, he became famous and

much-loved in the process. How was this possible?

Now we recall that Richard was

the son of Europe's

most famous mothers, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Eleanor just

happened be in charge of running England while Richard was

out of the country. Queen Eleanor originated the enduring

legend of ‘Good King Richard’ as a PR campaign by to persuade the citizens of the Plantagenet

empire to fork over the crippling ransom.

The raising of the ransom was a remarkable achievement.

Negotiations for Richard’s release took the best part of a

year, and after strenuous diplomatic efforts by Queen

Eleanor of Aquitaine, the payment of 100,000 marks – an

enormous sum, perhaps twice the gross domestic product of

the whole of England at the time – and the handing over of

hostages, the King was released in early February 1194.

After his release, Richard briefly returned to England and

was crowned for a second time. One month later he went to

Normandy, never to return. His last five years were spent in

intermittent warfare against Philip II, his alleged former

boyfriend.

While besieging the

castle of Châlus in central France he was fatally wounded

and died on 6 April 1199. He was succeeded by his younger

brother John.

John? John who? Surely not

the same Prince John who was the villain in

the Adventures of Robin Hood??

Yup, same guy. After all those

years spent scheming during Richard's absence, John ended up

being the King after all. And why was John made King?

Because the guy historian Dr. John Gillingham claimed was

straight didn't bother to produce an heir!

So how did John turn out? Not

very well. John has been termed 'the worst king in

English history'.

Short and fat, John was jealous of his

dashing brother Richard I whom he succeeded. John was

cruel, self-indulgent, selfish and avaricious. The

raising of punitive taxes united all the elements of

society, clerical and lay, against him. The Pope

excommunicated him and the English barons ganged on him.

On 15th June 1215 at Runnymede the barons compelled John to

sign Magna Carta, the Great Charter, which

reinstated the rights of all his subjects. John died

from over-eating. He was in hiding at the time, a

fugitive from all his enemies.

Let's

face it, when all was said and done,

Richard the Lionheart didn't accomplish much.

Richard lived to the ripe old age of 42. For

ten of these years,

1189-1199,

he theoretically ruled England...

History

suggests Richard spent at most six months of his

life in England. So here are the facts:

Richard

didn't win Jerusalem, he didn't produce an

heir, he ignored his country, he nearly bankrupted it with

his Crusades and his ransom, and stuck England with the

worst ruler in history.

And yet, if people in the streets of any

European city today were asked to name one English king,

many would probably answer ‘Richard the Lionheart’!!

How utterly crazy is that?

Fortunately Richard had a

good press agent... his Mom! During his reign, all the people back in

England heard nothing but good things about their missing

Good King

Richard. Even today Richard retains a similar good fortune...

or at least it did for a while. Back in the early days of Hollywood,

Richard was portrayed as a stud warrior, a defender of God,

a mighty Crusader and a noble King.

Richard's

reputation definitely benefitted from appearing

at the end of every one of a half-dozen Robin Hood

movies. Richard's modern-day

legend was built on

Robin Hood's modern-day legend and Robin Hood's legend was built on

Richard's and if you ask anyone, they will tell you

both

men were real

and both were great heroes. That's

Hollywood for you.

Recently Hollywood has been

less kind. Revisionist history seems to have caught up with

Richard. His reputation has taken a few hits, notably in

the movie 'Lion in Winter' where Richard can

be seen frolicking in bed with Phillip of France. So much

for my role model.

Wikipedia sums Richard up as

'a bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler, and a vicious

man. During his ten years' reign, he was in England for no

more than six months, and was totally absent for the last

five years.'

And did Richard die a noble

death? Not exactly. Richard died rather ingloriously from

gangrene following a crossbow

bolt wound in his shoulder.

Was Richard shot in battle?

No, Richard was walking

along the walls of his castle without his armor on. Some

kid down below took a potshot and hit him. Now that I

think of it, an Archer killed King Richard. No wonder I

have identity issues... I am at war with myself.

For a kid who grew up

worshipping Robin Hood and King Richard, history has not

been kind to me. I thought I was

named for the finest King in English history only to realize

I was named for the most over-rated one. But you know, it could have been worse.

Think about all the

poor little German boys named 'Adolf'.

|

|

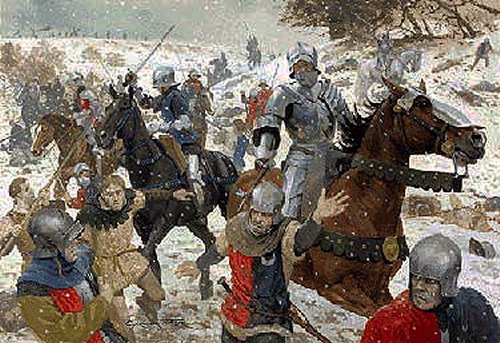

The Hundred Years War,

1337-1453

The Hundred Years War was fought over

ostensibly over the French Crown, but mostly it was

an excuse for English thugs and bandits to raid helpless

farmers and rape French girls. It was definitely

one of the most notable conflicts of the Middle Ages.

For 116 years, five generations of kings from two rival

dynasties fought to control the throne of the

largest kingdom in Western Europe.

If you ever wonder why the English

hate the French, think back to William the Conqueror who

imposed his French way of doing things onto England.

However, that resentment pales in comparison to the French

point of view. If you ever wonder why French hate

the English, start with

William the Conqueror and then follow the dots until you get

to the Hundred Years War. Virtually every English king

since William the

Conqueror brought havoc and misery to France

for centuries.

William the Conqueror was from Normandy, France.

Thanks to him, there was a succession of English Kings with

deep French ties that made them feel entitled to seek the

French crown as well as the English crown. That is what the

Hundred Years War was all about.

The Romantics like to point out that

armies of knights and archers battled for King and Country

on the field of glory. What utter nonsense. 'Chivalry'

may have the code word of the day, but little decency was shown.

At the end of many battles, helpless prisoners were

murdered in cold blood because the victors didn't feel like

feeding them. Unless a guy was worth some money in ransom,

it was easier just to slit his throat at the end of the day.

One time the English captured John II, the King of France,

in the 1356 Battle of Poitiers. The English set the

ransom price so high that the French had no choice but to

tell the English to go ahead keep him.

According to Stephen Clarke, author of

1000 Years of Annoying the French, the Hundred

Years War was basically used by the English as an excuse to

inflict 116 years of terror on French civilians. This

terror was conducted by out-of-control English bandits who

claimed to defend their king's rights. The truth was

they were actually hard at work enriching themselves and

having fun massacring as many helpless peasants as they

could.

As Clarke pointed out, for more than a

century, no town in the northern part of France was safe

from siege and plunder. Peasants could not work in

their fields without posting lookouts on hilltops, church

belfries, or up in trees. If a dust cloud was sighted,

the farmers would throw down their tools and run for their

lives. They knew that any man caught would either be

held to ransom if he was rich or put to death. Was the

death swift according to the prevailing sense of chivalry?

Are you out your mind? Chivalry? Absolutely not.

Each man was tortured hideously until he revealed where his

meager savings were hidden and where his wife and daughters

were hiding. Then the English would plunder the money

and rape the women. This was basically 100 years of

Genocide. Adding insult to injury, the Black Plague

took place and removed another 25% of the French population.

There's an old saying, 'Won the

battle, but lost the war.' In the French case, the

saying should go, 'Lost all the Battles, but won the war'.

Although it is true that the French eventually expelled the

English in 1453, the cost to France was beyond horrible.

In addition to one humiliating defeat after another in the

early stages of the war, the French saw their people

slaughtered, their towns destroyed, and their countryside

ravaged. The cost in human suffering was inestimable.

600 years have passed, but the memory is still there.

So what caused this brutal holocaust?

Don't worry, I will be brief, you can always count on that.

| |

|

|

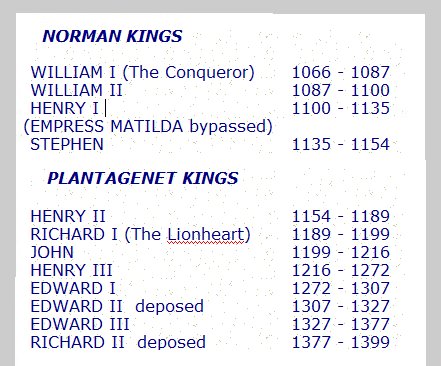

Henry II's successor was his son Richard I.

Like his father, Richard was 99% French. He

was born to French parents and was raised in France. We remember that King Richard the Lionheart spent

all of six months in England out of ten years of his reign.

When he wasn't off Crusading or being ransomed, he spent the

bulk of his time in France trying to extend his French

holdings. In other words, one of the most famous kings

in English history was 95% French and 1% English.

Sorry to say, Richard was a

bust and so was John, 'the worst king in English

history'. Henry III, John's son, wasn't

much better.

Edward I, also known as Edward

Longshanks, was perhaps the most successful of the

medieval monarchs. His reign marked a high point of

cooperation between crown and community.

However, we remember Edward the best as the villain

of Braveheart, the tragic movie about

Scotland's William Wallace.

Edward II was a waste of time.

Edward was a weak and incompetent king who spent

most of his time with his gay lovers. However,

he did marry and produced four children. The

eldest son, Edward III, would go down in history.

Edward III was a significant king in

English history. By my count, Edward was responsible for 150 years of war, 16 children,

and untold amounts of misery.

|

|

|

|

Edward III

Edward III ruled for 50 years,

(1327-1377), one of the longest reigns of any

European monarch. The sixth English King after

the renowned Henry II,

Edward was at heart a warrior. Edward III transformed

the Kingdom of England into one of the most

formidable military powers in Europe. His long

reign of fifty years was the second longest in

medieval England. Edward oversaw vital

developments in legislation and government, in

particular the evolution of the English parliament

Edward III was crowned at age fourteen after his weird

father was deposed by his mother, Isabella of

France, and her lover Roger Mortimer. At age

seventeen, Edward led a successful coup against

Mortimer, the de facto ruler of the country, and

began his personal reign. After a successful

campaign in Scotland, he turned his attention to France.

Edward declared himself rightful heir to the French throne

in 1337.

However, when his claim was denied,

he decided to attack France and press his claim. This started

he Hundred Years' War.

Edward's claim on the French throne was based on his descent

from King Philip IV of France, through his French mother

Isabella. His marriage to French princess Philippa

further reinforced his claim.

They always say make love, not war.

Well, Edward did both. Philippa and Edward had

thirteen children, including five sons who lived into

adulthood. The rivalry of those numerous descendants

would one day bring about the long-running and bloody

dynastic wars known as the War of the Roses.

|

As it turns out, Edward had a famous

mistress. Alice Perrers (1348–1400)

was a royal mistress whose lover and patron

was King Edward III of England. She met him

originally in her capacity as a

lady-in-waiting to Edward's consort,

Philippa of Hainault. Alice Perrers was despised

by many and was accused of taking advantage

of the far older king with her opportunistic

character, youth,

and beauty. Meanwhile, this mistress went on to become

the wealthiest woman in the land.

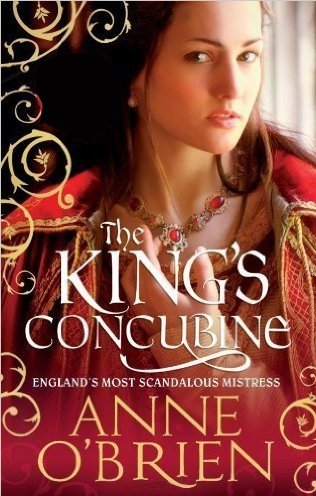

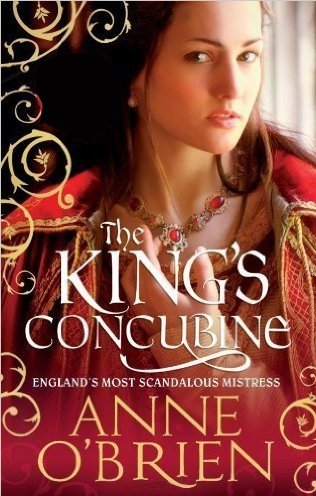

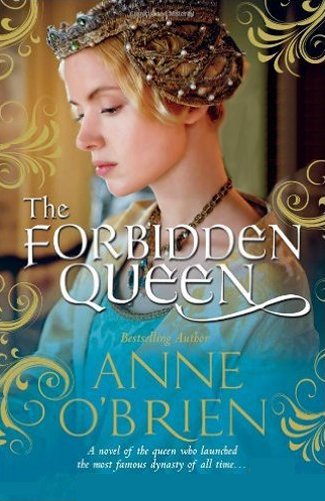

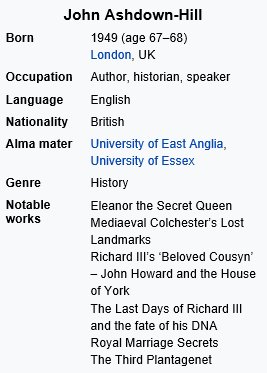

As we shall see, History is just as

fascinated by the women surrounding the

Kings as the Kings themselves. Anne

O'Brien is a former history teacher in

England who turned to historical fiction.

Let's see what she has to say about Alice

Perrers:

One marriage. Three

people. Proud king. Loving wife. Infamous

mistress. 1362.

Philippa of Hainault selects a young orphan

from a convent. Alice Perrers, a girl born

with nothing but ambition. The Queen has a

role waiting for her at court.

‘I have lifted you from nothing Alice. Now

you repay me.’ Led down the corridors of the

royal palace, the young virgin is secretly

delivered to King Edward III – to perform

the wifely duties of which ailing Philippa

is no longer capable. Power has a price, and

Alice Perrers will pay it. Mistress to the

King. Confidante of the Queen. Whore to the

court.

Her fate is double edged; loved by the

majesties, ostracized by her peers. Alice

must balance her future with care as her

star begins to rise – the despised concubine

is not untouchable. Politics and pillow talk

are dangerous bedfellows.

The fading great King wants her in his bed.

Her enemies want her banished. One mistake

and Alice will face a threat worse than any

malicious whispers of the past.

|

|

After his wife Philippa died, Edward had three

illegitimate children by his mistress Alice Perrers.

This brings our total to at least 16 children.

There might be more, but who has the patience? I found a website that drew a very unusual

statement

about Edward:

Conclusion: there is an extremely

high probability that a modern English person with

predominantly English ancestry descends from Edward III,

at a very minimum over 99%, and more likely very close

to 100%. The number of descendants of Edward III must

therefore include nearly all of the population of

England, and probably much of the populations of the

rest of the UK and Eire, as well as many millions in the

USA, former British colonies and Europe, so 100 million

seems a conservative estimate. Documenting one's own

descent from Edward III is, however, another matter!

There are two other footnotes to the

reign of Edward III.

First, England lost 33% of its population

due to

the Black Plague.

Second, France lost 33% of its

population to Edward's son, the infamous Black

Prince. No, France didn't really lose that

many, but it sure seemed that way.

|

The

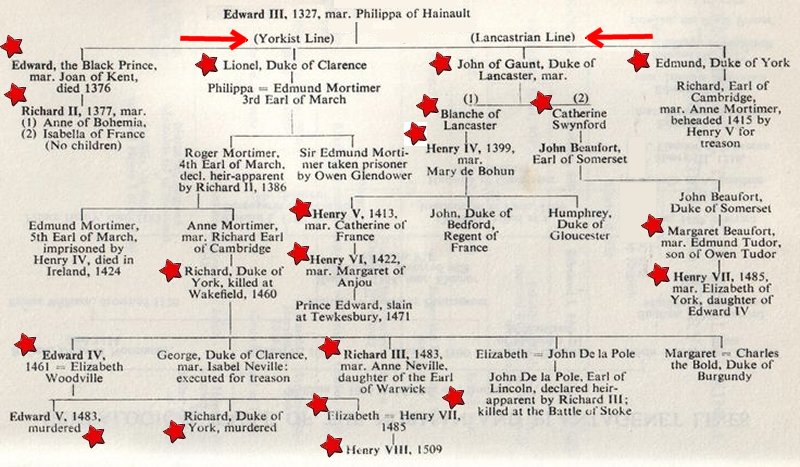

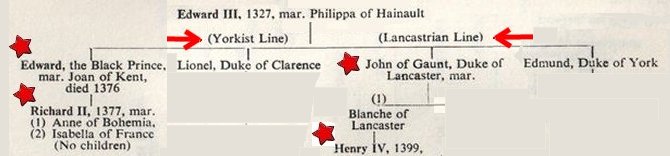

Lineage of Edward III

|

I have

discovered the hard way that any American who

undertakes the task of sorting out English genealogy and

ancestry is an idiot. There are some

remarkable stories to be told, but unless I explain

the complicated politics, the upcoming stories will

not make much sense. Therefore, after much

frustration, I have concluded that at least a

superficial understanding of what King Edward III

did would help

explain the complex story behind the remarkable

events soon to unfold.

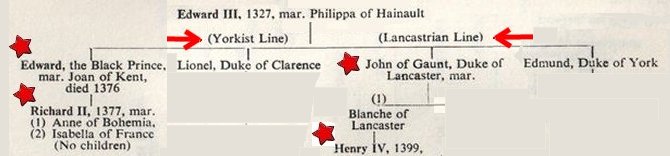

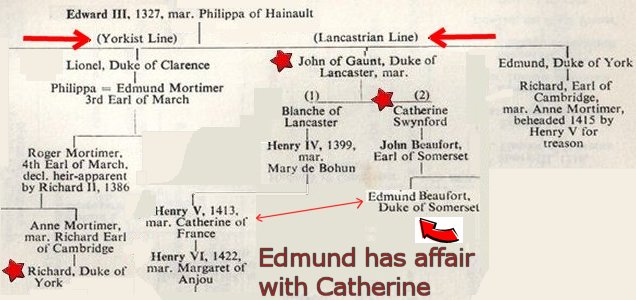

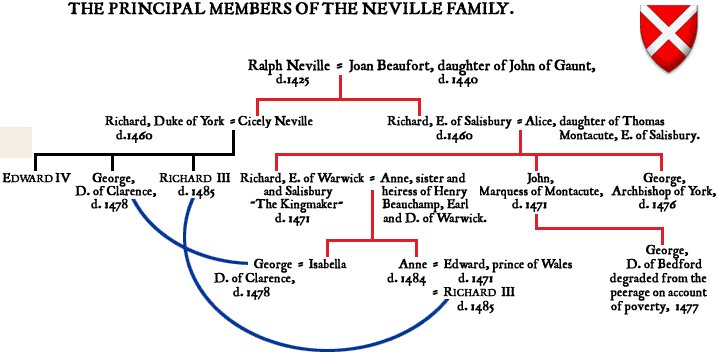

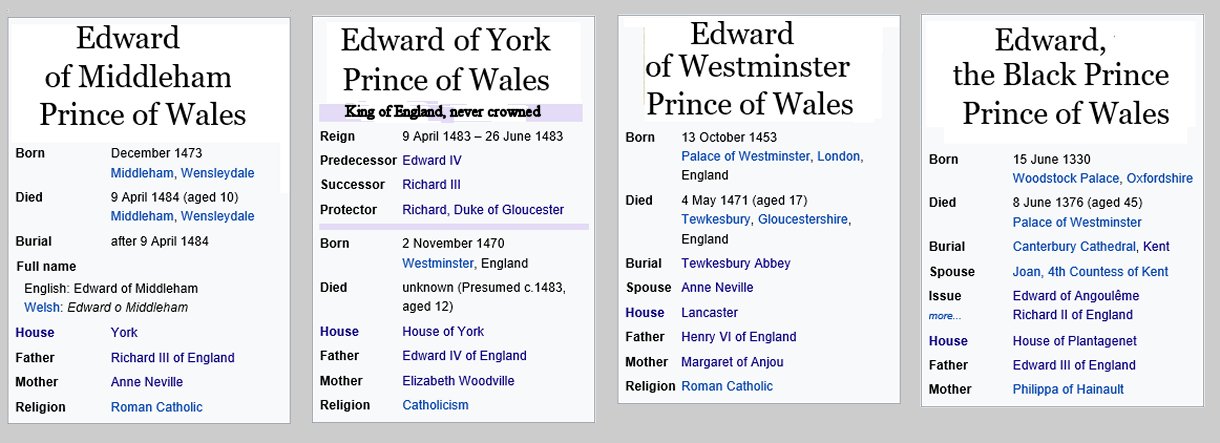

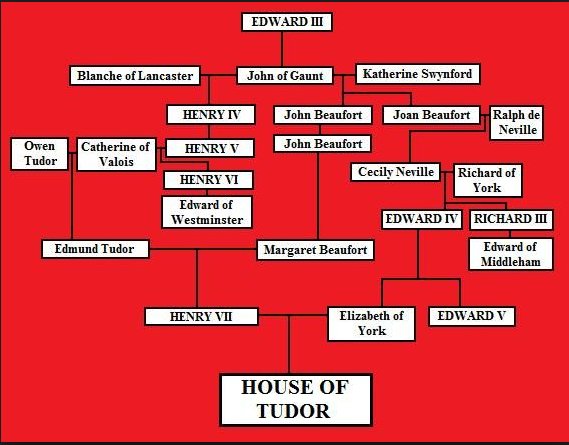

All four

of Edward III's sons contributed directly to English

history.

•

Edward III named John of

Gaunt, one of his sons, to become the Duke

of Lancaster.

•

Edward III named Edmund,

another other son, to become the Duke of

York.

•

Edward III had yet another

son, Lionel, whose descendent Richard,

Duke of York, would play a key role in

English history.

•

Edward III's son Edward,

also known as the Black Prince, would see his

son Richard II succeed Edward III as king.

Now that Edward III's four

boys have split off into different Houses, both

Houses had an equal right to promote one of their

members to the English throne. This splitting

would lead to brutal competition starting three

generations down the line.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

Edward, The Black Prince

|

| |

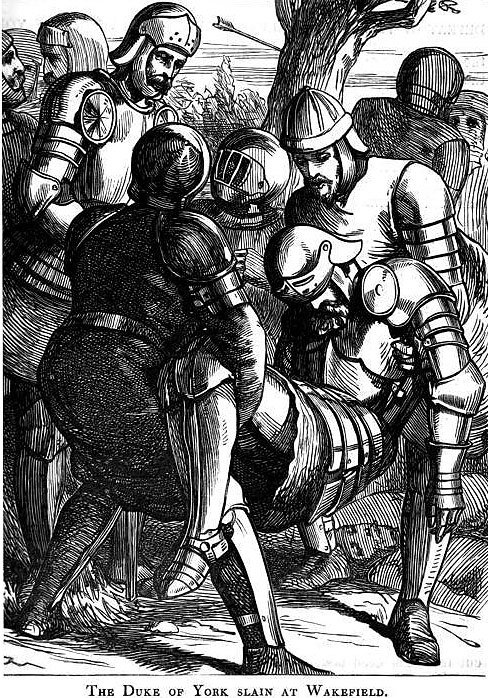

The most hated man

in France was the Black Prince. Sorry to say, but the French

got the worst of it during the Hundred

Year's War because all the battles took place

on French soil. The Black Prince was quite a

warrior.

Like father, like

son.

Although

the Black Prince was the

eldest son of King Edward III and Philippa of Hainault,

Edward of Woodstock (1330 –1376)

never became

king. He died one year before his father's death

after fighting a prolonged ten-year battle with a

mysterious, debilitating disease.

Due to his premature death, the throne passed instead to his

son Richard II, a minor, upon the death of the Black

Prince's father Edward III.

Edward of Woodstock was an exceptional military leader. His victories over the

French at the Battle of Crécy and the Battle of Poitiers

against superior numbers during the Hundred Years War

made him very popular in

England.

Unfortunately, Edward was

not a man of mercy. In fact, he was the

Black Prince of Destruction

who laid

neverending waste to France during the Hundred Years War.

Although this was

considered the Age of Chivalry, Edward never got the email.

Edward had a well-deserved reputation for

cruelty. He earned his title based on his habit of burning

the fields of his French enemies, laying waste to the towns

that he conquered, and executing thousands

of

helpless, unarmed French prisoners after his

battles.

He was despised by the French and admired by the

English. Whatever your point of view, there can be no doubt

that Edward was a brute. Hence

the name 'Black

Prince'. The only favor Edward

ever did the French was to die young, thereby

putting one of England's worst rulers on the throne.

|

|

|

| |

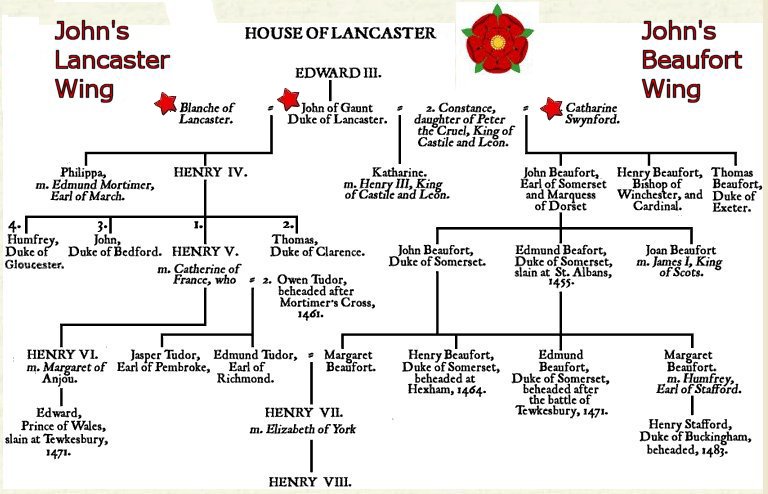

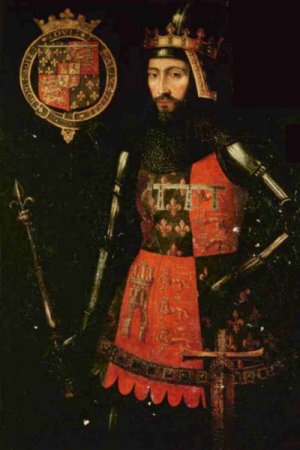

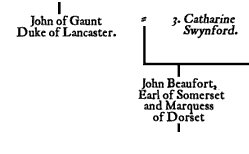

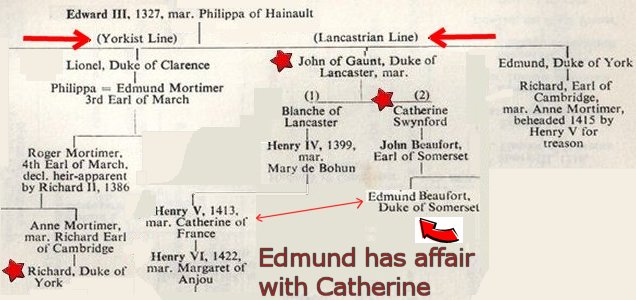

John of Gaunt,

House of Lancaster

#1 and House of Lancaster #2

|

Good old

King Edward III... remember him?

Edward III

was the king who started that awful Hundred Years

War and also found time to reproduce at a prolific

rate.

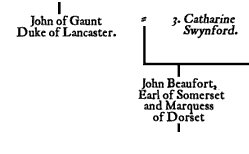

Edward's third male child by his wife Philippa was known as John of Gaunt.

John of Gaunt founded not one,

but two major wings on the House of Lancaster

family tree.

One wing

was

founded with Blanche of Lancaster, his first wife.

The second wing was founded with Katherine Swynford,

his mistress of 30 years.

Both

women were quite remarkable.

|

|

|

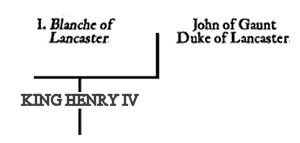

John of Gaunt and

Blanche of

Lancaster

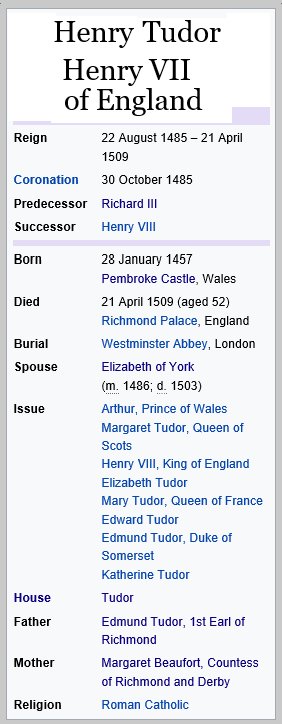

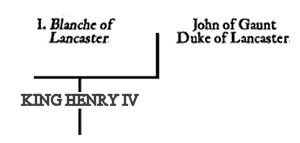

King

Edward noticed that Blanche of Lancaster,

daughter of Henry Grosmont, head of the original

wing of Lancaster, was not only filthy rich, she was

available.

So John

of Gaunt married Blanche of Lancaster in 1359.

She was 14 at the time. Since John was a

Plantagenet and the Lancasters were also

Plantagenets, I suppose they were cousins of a sort.

|

Blanche

possessed considerable land holdings. After

John

combined the estates King Edward gave him plus Blanche's

estate, John of Gaunt was now the richest man in

England after his father King Edward III.

Blanche

was remarkable... marrying at age 14, she had seven

children in eight years. Then suddenly she

took ill from complications following the birth of

her seventh child. Blanche died in 1368 at age

22.

One of

Blanche's children was Henry Bolingbroke, destined

to become the first Lancaster King, Henry IV.

After

Blanche's death, John had pretensions of ruling a

Kingdom. He was too far removed from the Crown

of England to expect advancement, so he married Constance of Castille,

Spain, in 1371. John

of Gaunt huffed and puffed for the next 23 years or

so, but the Spanish Kingdom gig never worked out.

Constance died in 1394 still married to John. It would be

interesting to know what Constance thought of her

marriage. However,

for the sake of Brevity, I will do my best to look

away. On the other hand, John's next love

affair was more than I could resist.

|

| |

|

|

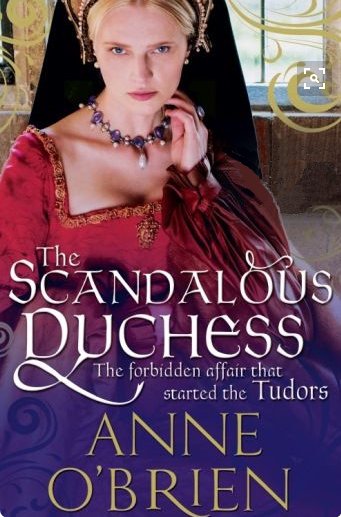

Katherine Swynford,

The Scandalous Duchess

|

|

Widow Lady Katherine

Swynford presents herself for a role in the

household of merciless royal prince John of Gaunt,

Duke of Lancaster, hoping to end her destitution.

But the Duke’s scandalous

proposition leaves her life of pious integrity

reeling... Seduced by the glare of

royal adoration, Katherine becomes John’s mistress.

She will leave behind

everything she has stood for to play second fiddle

to his young wife and ruthless ambition.

She will live in the

shadows of the most powerful man in England in the

hope of a love greater than propriety.

But soon the court whispers

– whore, harlot, vile temptress – reach the ears of

not just John’s bride but his most dangerous

political enemies.

As the Plantagenet prince

is accused of bringing England to its knees, who

better to blame than shameless she-devil Katherine

Swynford?

Dragged from the shadows,

Katherine must answer for her sins.

|

|

Katherine Swynford was a commoner who came to the

household of John of Gaunt as governess to his

daughters Philippa of Lancaster and Elizabeth of

Lancaster.

After

the death of his wife Blanche, John made Katherine

Swynford his mistress. She bore him four

children in the years between 1371 and 1379.

They were supposedly born in John’s castle in

Champagne, France, and given the name of the castle

as their surname; Beaufort. However it seems

just as likely that they were named after the

lordship of Beaufort, which had one belonged to

Gaunt and to which he still laid claim.

Katherine remained John's mistress for 30 years

during his marriage to Constance. How she put

up with this situation is anyone's guess.

That

said, for you hopeless romantics, I will share one

tidbit... John finally married Katherine in 1396 and made

her the Duchess of Lancaster. He then asked

King Richard II to legitimize their four children.

The

House of Beaufort had begun.

It is interesting to note that a descendant of

Katherine's previously illegitimate son John

Beaufort would on day produce a King

of England.

|

|

|

| |

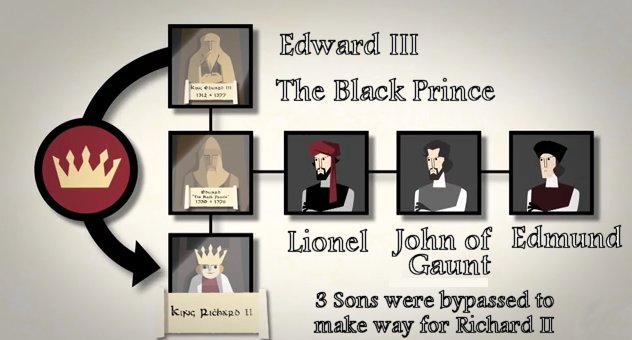

Richard II

Richard

II followed Edward III.

Richard was

not the son of Edward III, but rather the

son of the Black Prince. Richard II

was 10 when his controversial father died of a

mysterious ailment in 1377. No doubt the

French were thrilled to see this brutal man bite the dust.

|

|

| |

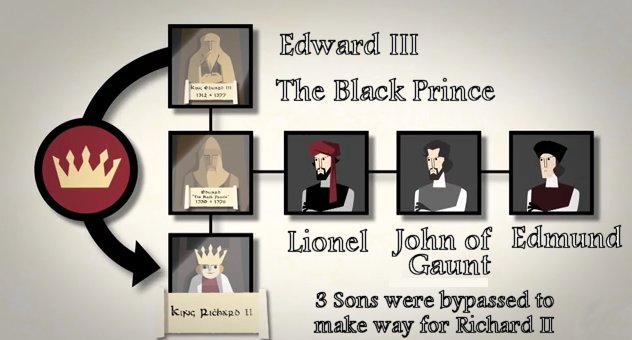

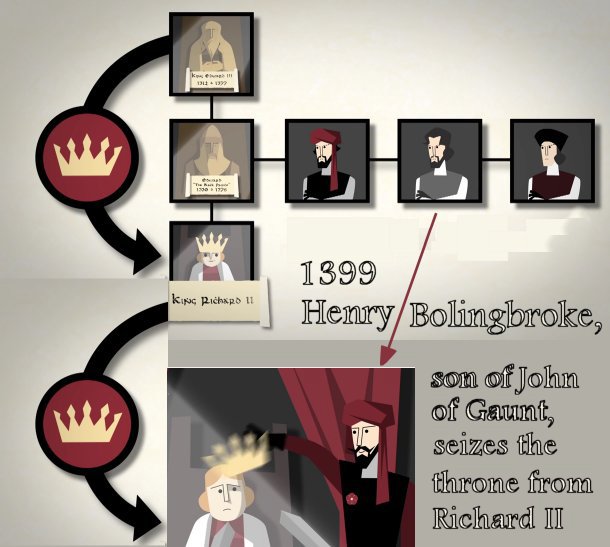

In a move that would have far-reaching

consequences, Richard II bypassed three

able-bodied sons for succession to the

crown.

By the laws of primogeniture, this ten year

old boy, Richard II, succeeded to the throne

ahead of Edward's three surviving sons

This skipping of an entire generation left

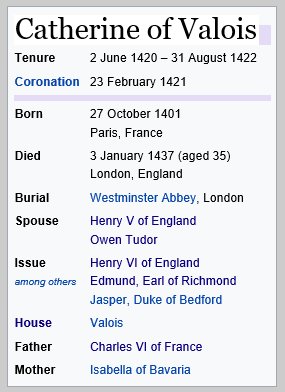

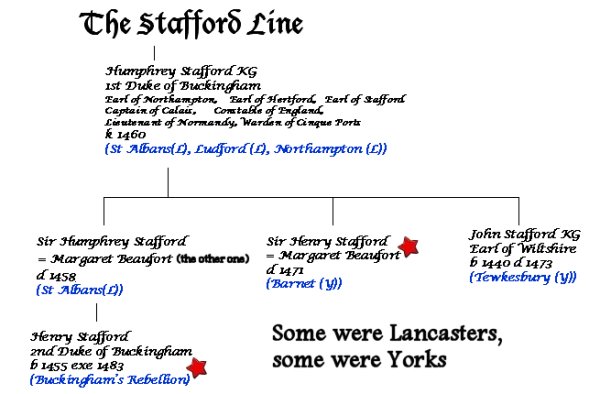

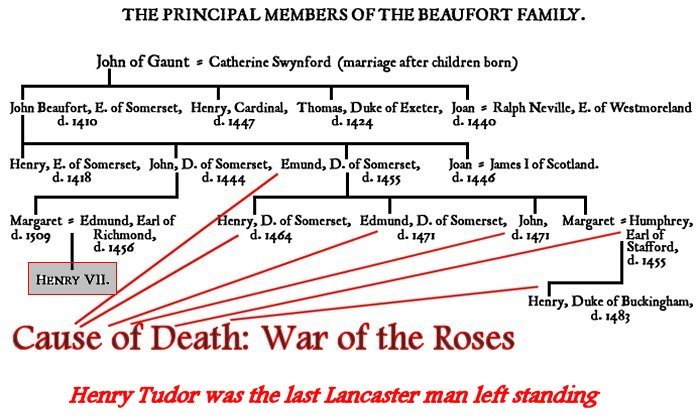

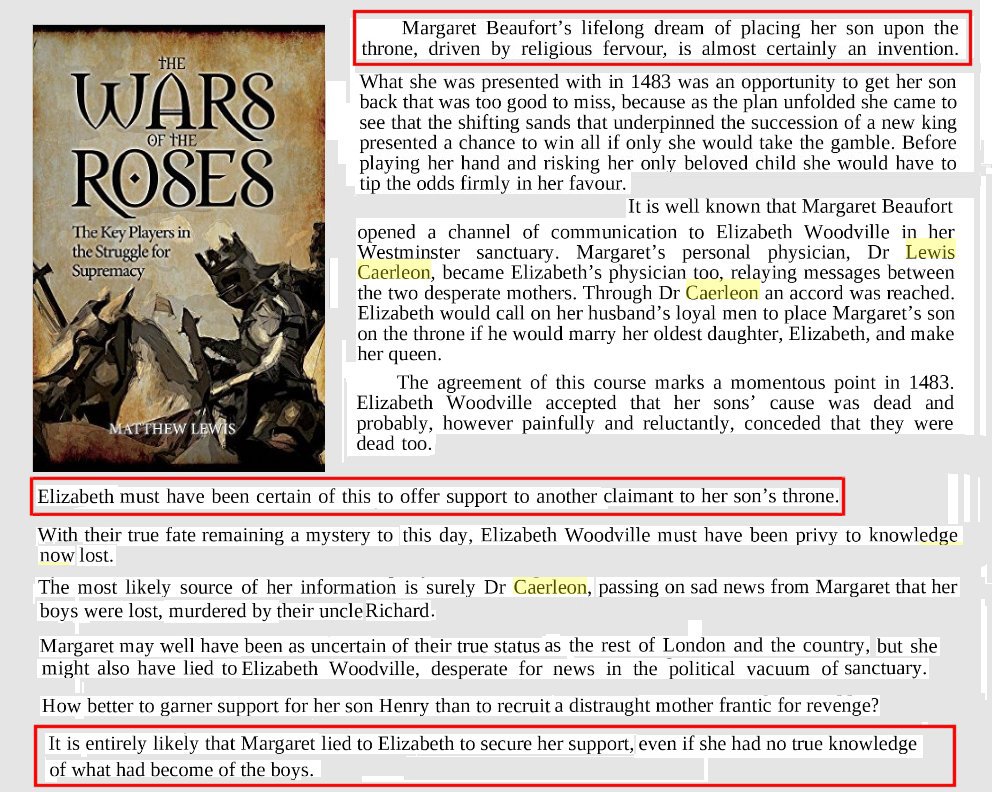

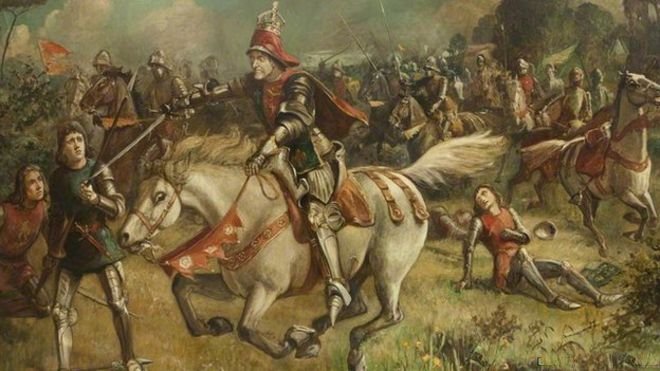

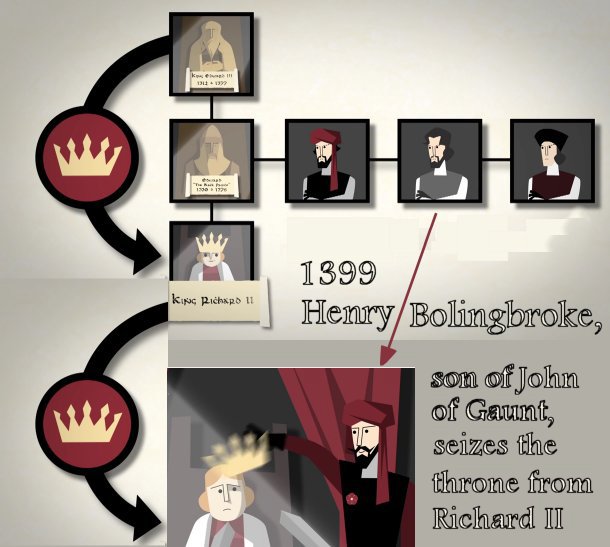

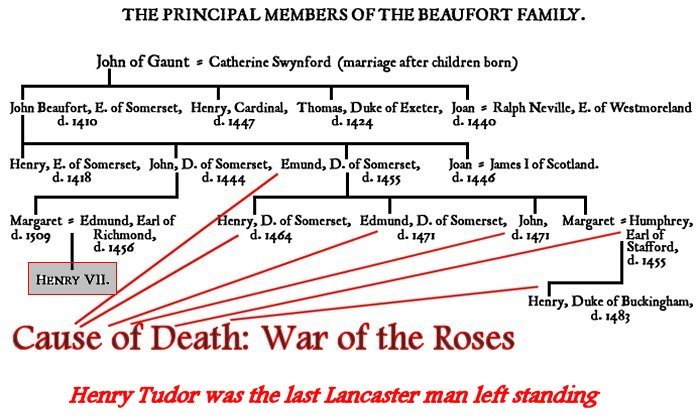

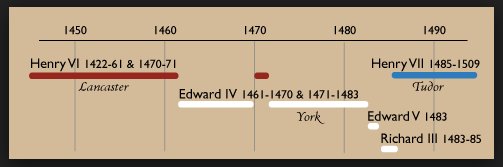

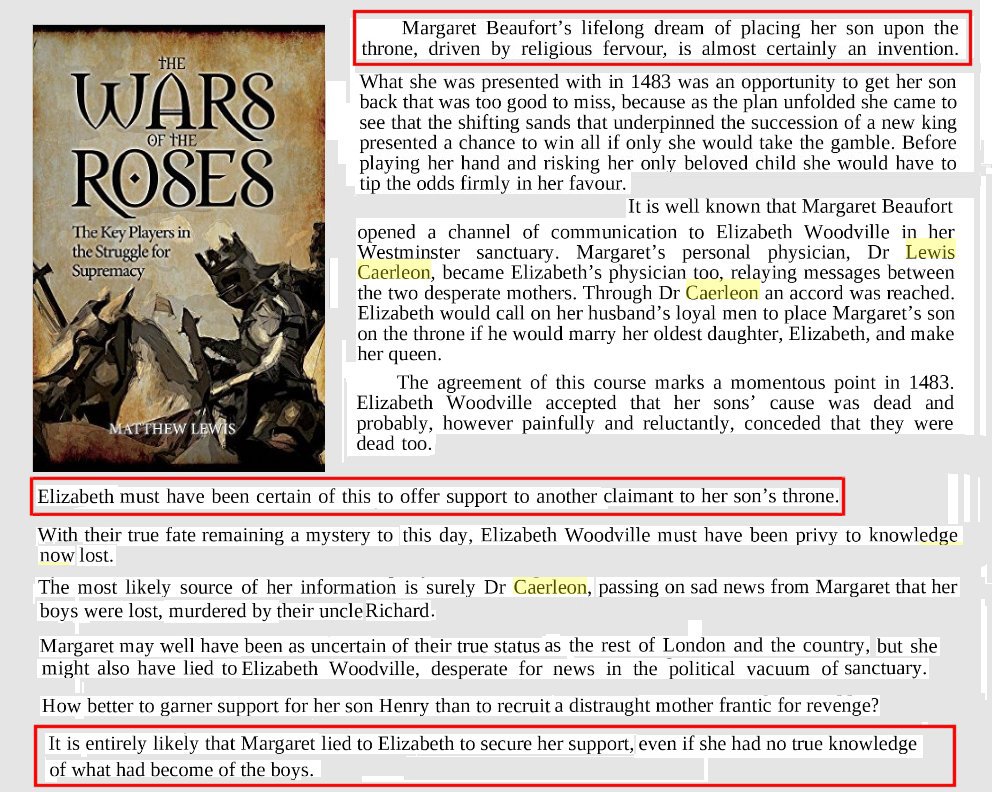

lingering claims to the throne among their