Chapter 6 -

Reflections on D-Day

Story written by Rick Archer

|

The Remarkable Sgt Streczyk

|

Rick Archer's Note: During my research, I poked my nose

into six different books and probably twenty different websites looking for

information. Sgt Phillip Streczyk's name popped up in

every story I read about this day with amazing frequency. Everything ever said about the man was full of tremendous praise.

Lt John Spalding, DSC recipient, on Streczyk:

"My assistant section leader was T/Sgt Phillip Streczyk. The

sergeant, who was later wounded in the Hurtgen forest action, was the best soldier I have ever seen.

He came into the army as a selectee and worked his way up to platoon

sergeant. He was in on landings at Oran and in Sicily. If we had

more men like him, the war would soon be over."

Captain General Ed Wozenski

on Streczyk: "Sergeant Streczyk

was one of my platoon sergeants. I think that he’s the

greatest unsung hero of World War II. To the best of my knowledge, he was the

first one on the beach and it was the path that he took that I

picked up. The rest of our battalion followed, 2nd Battalion 16th

Infantry, and then later on I think almost the whole corps went up

that same path."

Sgt. Clarence

Colson, DSC recipient, on Streczyk:

"He wasn't West Point material but I'll tell you what: there wasn't

a braver man that ever walked the ground."

Pfc. Bruce Buck

on Streczyk:

"Streczyk was good. He knew what he was doing."

|

|

|

Citation:

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the

Distinguished Service Cross

to Phillip Streczyk, Sergeant,

U.S. Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military

operations against an armed enemy while serving with Company E, 2d

Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division, in action

against enemy forces on 6 June 1944 near Colleville-sur-Mer, France.

In the face of vicious enemy fire, Sergeant Philip Streczyk led his

section across the beach.

He cut through the

enemy wire,

led his platoon

through a minefield and up a steep hill overlooking the beach and by

this action opened a beach exit. He then led his section in an

attack on an enemy emplacement, the fire from which had prevented

the establishment of a vitally needed beachhead in that sector.

In a vicious fight, Sergeant Streczyk set the example for his men in

leading the attack. The destruction of this enemy strongpoint

contributed materially to the success of the invasion effort.

The valor, initiative and disregard for his own safety exhibited by

Sergeant Streczyk exemplify the highest traditions of the military

forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself,

the 1st Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

|

Contradictions

One

of my favorite resources for studying D-Day was an excellent website known

as

War

Chronicle.

More than half of what I have written for this chapter was based on

material that came from

War Chronicle. The W.C. website has a special section

devoted to

Soldier's Tales

in the First Infantry Division that the men belonged to. Lt

John Spalding and Phillip

Streczyk were part of the First Infantry Division, better known as

"The Big Red One". The Big Red One was a fabled fighting unit

that got its name from a shoulder patch with a red '1' on it.

On the War Chronicle website there are oral histories from Spalding, Capt Wozenski, Bieder,

DiGaetano, Colson, and several others.

As I read through those different stories, it became readily

apparent that there were several glaring inconsistencies. For

example, Spalding stated that Louis Ramundo was killed at the beach.

"Pfc. Lewis J. Ramundo was killed here,

the only man killed in my

section on the beach at D-Day."

On the other hand, Clarence Colson distinctly remembered

Ramundo getting killed shortly after Colson took out a pillbox

single-handedly up on top of the ridge. Colson claimed a

sniper got Ramundo as he went down the hill. Considering Spalding

said he only lost two men all day (Fred Bisco died in the afternoon at

Colleville), you would assume Spalding would remember the correct

location of Ramundo's death. And perhaps he did. Maybe

Colson got it wrong.

In Spalding's oral history, he distinctly remembers DiGaetano

ditching the

flamethrower into the water.

Spalding's words: "About this time Pfc. Vincent DiGaetano, who was

carrying a 72 pound flamethrower, yelled and said, "I'm drowning,

what do you want me to do with this flamethrower?" Streczyk told him

to drop it, so he did. In addition to the flamethrowers and many

personal weapons, we lost our mortar, most of the mortar ammunition,

one of our bazookas, much of the bazooka ammunition."

After that, Spalding never mentioned the flamethrower again in his

oral history.

However, in Vinny DiGaetano's oral history, he specifically said,

"We got the flamethrower

out and went to a pillbox [at WN64]. The

Germans come out, Aaaaah! They didn’t even know we had a frigging

flamethrower. They were hiding in the back or something. If you get

them, they know about it. Had to be like napalm. In 30 seconds, or a

minute, all gone. The tank was empty. Goodbye."

Another contradiction I found dealt with casualties in Spalding's

company. Spalding said 2 men died. He took in a boat of

32. So why did he wander around that hill all day with 20-22

men? Streczyk's report said they lost 12 of 32 getting to

shore.

"Streczyk

got 32 men onto the sands, took 12 casualties mostly from bullet

fire in getting across the beach, and continued onward immediately

with 20 men."

16-E Report Obviously Streczyk's report seems to make

more sense.

Personally, it really doesn't matter very much at this point.

I only care because I was trying to piece together a reliable story.

In the cosmic scheme of things, D-Day took place nearly 70 years

ago and we won the battle. So obviously contradictions like these are no big deal.

But I found lots of

contradictions... which makes perfect sense because so much happened that day.

There is even a term for it... "the fog of war". If facts

can't be reconciled, the historians chalk it up to "the fog of war".

Spalding clearly respected his talented Sgt Streczyk. He said,

"My assistant section leader was Sgt Phillip Streczyk. The

sergeant, who was later wounded in the Hurtgen forest action, was the best soldier I have ever seen.

He came into the army as a selectee and worked his way up to platoon

sergeant. He was in on landings at Oran and in Sicily. If we had

more men like him, the war would soon be over."

|

So now it is time to bring up a contradiction that is a real

headache. Streczyk's DSC

citation read:

"He

cut through the enemy wire..."

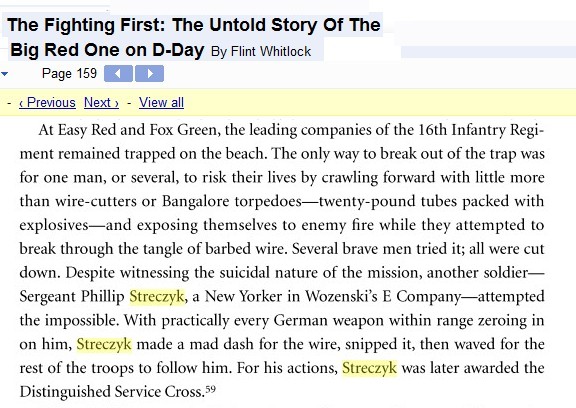

In his book The Fighting First, Flint Whitlock clearly

described a remarkable story of how Streczyk bravely rescued the

D-Day invasion by risking certain death to create the

first opening of the entire day!

[Read caption]

The caption describes an effort so heroic that I would say Streczyk

deserves the Medal of Honor! But there seems to be some

sort of problem here.

John Spalding had this to say about the

barbed wire incident, "Down

near the water's edge we ran into wire.

S/Sgt. Curtis Colwell

blew a hole in the wire with a

bangalore. We picked our way through; I personally didn't see

the gap he had blown, but I was still in a daze."

As I researched this story, it bothered me no end that Lt. John

Spalding would praise Streczyk so highly in his post D-Day

interview, then completely fail to mention how Streczyk had

risked his life to advance the troops at the barbed wire. This

obvious discrepancy made absolutely no sense to me!

|

|

Ask yourself this question: Thousands of men are pinned down

by withering fire on the beach. No man dares move or risk

death. Sooner or later the German tanks are going to show up

and send every one of these men to oblivion. Desperate to

survive the killing fire, one man rushes to the wire and is gunned

down. Another man rushes to the wire only to be gunned down as

well. There are two dead bodies as a reminder to all that

there is no chance in hell of success. Amazingly, a third man

- Streczyk - rushes to the wire and

risks his life to cut the barbed wire, the act of which provides the

absolute turning point of the day. Now here is the

question: If the fate of your entire company, much

less the entire V Corps, much less the success of the entire Allied

Invasion rested on breaking through that barbed wire and your

Sergeant leapt down on the ground and furiously begin snipping away

while bullets struck the ground just inches from his face - an act

of incredible heroism - do you think you would remember that?

Do you think you would get the guy's name straight?

I think, yes, we can all agree we would remember that incident and

get the facts right. No fog of war could possibly make us forget

the incident or get the wrong guy.

Spalding struck me as an intelligent man. He remembered all

sorts of details. His oral history is six pages long and full

of times, names, and incidents. It is a lucid, coherent

document.

So how on earth did Spalding fail to mention the incident with

Streczyk and cutting the hole in the barbed wire? After

all, that was an amazing action that should have earned Streczyk a

Medal of Honor! Did Spalding's glaring omission cost Sgt

Streczyk the highest possibly honor our country can bestow?

I doubt it. That's right, I doubt it. I do not think Streczyk cut that wire. I want to believe Streczyk was an

incredible hero - and barbed wire or no barbed wire I still think he was an incredible hero - but

I don't think he cut that wire.

I believe it happened just like Spalding said - Colwell blew a hole

in it with a bangalore torpedo. Furthermore, there was no

heavy fire. It probably wasn't anywhere near the suicidal mission

Whitlock described.

Nor do I believe there were dead people who had failed trying to cut

that wire before Streczyk.

I think that entire story is nonsense. This sector of the beach was in a

rare area of reduced gunfire; we discussed that in the previous

chapter. Dawson's men

nearby didn't have any trouble blowing their barbed wire, so why

should Spalding's company have trouble either?

Don't get me wrong - based on what I read, I am huge admirer of

Phillip Streczyk. If this really happened, I think we should

all stand up and applaud! Then we should demand his war record be reviewed

and get him that Medal of Honor!

However, like I said, I don't think Streczyk was robbed on wire

cutting issue.

I think the culprit here is one of two people.

One possibility is that Mr. Whitlock, author of the Fighting

First (2005), either let his imagination get carried away or

accidentally copied someone else's faulty information. Before

anyone be

too quick to judge, let me say I am sure I am guilty of the same thing

- I wrote this entire story about D-Day based on other people's

reports!

I have no way of knowing the 'truth' of everything I have written.

That said, I think Mr. Whitlock's passage about Streczyk is clearly

wrong. Here

is something I found on the Internet:

Distinguished

Service Cross To Curtis Colwell, awarded for actions

during the World War II

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act

of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the

Distinguished Service Cross to Staff Sergeant

Curtis Colwell

(ASN:

6662084), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in

connection with military operations against an armed enemy while

serving with Company E, 2d Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment,

1st Infantry Division, in action against enemy forces on 6 June

1944, in France.

Under the heavy

enemy rifle, machine gun and artillery fire of the enemy, Staff

Sergeant Colwell fearlessly cut a gap in the wire. He then led

his section through this gap in the wire and through the mine

field beyond the wire.

As his section

approached its objective it came under fierce enemy machine gun

fire. Completely ignoring his own safety, Staff Sergeant Colwell

led his section in a successful assault upon the machine gun

position. Staff Sergeant Colwell's determined leadership,

personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty exemplify the

highest traditions of the military forces of the United States

and reflect great credit upon himself, the 1st Infantry

Division, and the United States Army.

So a DSC was given to two different men in the same company and both citations mentioned

the barbed wire. I suppose it is always possible that

Streczyk, not Colson, was indeed the man who cut the wire.

Mr. Whitlock wrote THE UNTOLD STORY OF

OMAHA. Perhaps Mr. Whitlock has learned something new.

Maybe he uncovered the secret of who really cut the wire. If so, then Mr. Whitlock should come forward and make sure Phillip

Streczyk receives his long overdue medal.

But I doubt that is the case. My money is on Colwell.

Another possible culprit behind the discrepancy might be the mysterious

16-E Report (16th Infantry, E Company). This was a

report of the events of the day written shortly after D-Day ended. This report

is an unsigned and undated field report. It was rumored to be

written by the famous war historian SLA Marshall. This 16-E

report seems like it was the first documentation of the events of

D-Day for Company E.

In the 16-E report, Phil Streczyk's name is quoted 13 times.

Spalding's name is not mentioned once. In fact, this entire report

reads like Streczyk was the only man on the field that day.

Here is an excerpt:

Streczyk’s

section—which was to contribute one of the most intrepid

actions of the entire day—came in exactly where “F” was supposed

to land. (See overlay: The place of landing was identified by

Streczyk’s surviving members and by Streczyk during

the interview.)

Streczyk got 32 men onto the sands, took

12 casualties mostly from bullet fire in getting across the

beach, and continued onward immediately with 20 men. The German

strong point (WN62) —covering EXIT 3 on the eastern side—when the debouchement

took place was to the party’s immediate left, and from this,

they were drawing most of the fire.

Dead ahead of them was

a small ravine and their approach was direct toward it.

This put

them a little to the left of the first line of emplacements

serving as an outwork of the strong point WN64. A communications trench led

back from the emplacements. The party moved rapidly up the draw,

then went right and slightly up the hill in such a way that they

emerged on the rear of the outwork before the enemy had noted

the movement (Streczyk). The 14 Germans inside the work

were caught flat-footed. The party attacked them with grenades

and bazookas and they made a futile attempt to reply with

grenades: several were killed, two were captured and the others

got away.

The party then attacked strong point WN64 from the rear, and had its

rearward exit covered before a shot was fired. From the cover of

an outer trench, they engaged it with grenades. The enemy fire

gradually fell off as the occupants went to cover, but there was

no sign of a surrender. For 4 ½ hours, Streczyk’s men

stayed there, keeping this point neutralized and thereby greatly

assisting the movements of “G” and of other units across the

beach. Yet they did not feel strong enough to assault it

directly and under the conditions in which the men were

employed, the Streczyk party was wholly scattered with

each man fighting his own battle and doing whatever he could to

harass the enemy.

In this time they took 21 prisoners and left

an equal number of German dead behind without themselves losing

one man. They had kept under cover in the outworks, worked in

small groups through the trenches and gradually reduced the

enemy strength so that strong point WN64 was not capable of any strong

action. The strongpoint had not yet been conquered, but it

had become “contained.”

Streczyk’s men had blown the wire confronting the ravine just

after landing. There was thus a

convenient avenue for the

advance of other troops. Fitzsimmons, who had landed well over

to the left, came up shortly after 1100 and learned about the

breach. The Company Commander, Capt Edward Wozenski, then decided to

move laterally along the beach toward Streczyk and he and

Fitzsimmons set to work rounding up the men. They could only get

about 1 ½ squads together. Wozenski then tried to get smoke laid

on the beach to cover the movement to the right but this was

unavailing. The party then moved on along the beach.

Streczyk said that after getting to the top of the hill,

his party moved west, not east, and that in so doing, they

crossed the route by which Dawson and his men had moved inland

from the beach. He was positive that the party had moved to the

right after reducing the SP [Strong Point]. The other men agreed that

this was the line taken by the small parties which came up on

Streczyk’s rear. Fitzsimmons said that the groups which came

up later and took the same route were not seriously checked by

fire on the beach nor in their journey up the hill.

For someone said to be an 'unsung hero', someone was certainly

singing Streczyk's praises that day!

My guess is that whoever wrote this report interviewed Streczyk, but

not Spalding.

After Spalding's platoon had taken out

WN64,

Spalding stayed up top while Streczyk took the prisoners down to the

beach. The beach is where the reporter would be. Therefore Streczyk was likely the man first interviewed about the amazing

breakthrough. That said, why Spalding's name doesn't appear a

single time in the

report is a

fascinating mystery.

So what do you think? If you read that 16-E report and that report

only, you might conclude Streczyk was the unit leader and that

Streczyk was heavily responsible for the breakout. Don't you imagine if this was the first and only report of the events of D-Day and it

was allowed to circulate long enough, this report could be the

likely origin of the Legend of Phillip Streczyk?

Let me

clarify - Streczyk had every right to explain his role in the

remarkable accomplishment of taking out an entire Nazi stronghold

with only 20 men. That is amazing! But what about

Spalding? I find the whole thing curious. This must be the

'fog of war' in action.

There clearly was some monkey business in reporting the facts of the day on

someone's part,

possibly even more than one person, but let's keep one thing in mind

- whether Streczyk cut the barbed wire or not, whether Streczyk deliberately

forgot to mention his Lieutenant's name or not, the one undeniable truth is that

Phil Streczyk risked his life time and again on D-Day. Phillip Streczyk was

the main reason for the eventual

takedown of Strong Point

WN64.

Rick Archer's

Note: Here is my point. I am trying to create a

reasonably authentic recounting of what took place at Omaha

Beach on D-Day. That said, in my search for the

truth, I am handicapped in several ways. First, I am

depending on the words of both published writers and Internet

writers I do not know for their accuracy. In so doing, I

am well aware that most of these writers are just as dependent

as I am on other sources to get at the facts. Like the

Bible, every time a story gets retold by a secondary person,

there is a chance the facts get skewed a bit.

My other handicap

is that there is probably no living member of Spalding or

Dawson's unit to interview. Fortunately, there is

one source of new information... the children of the soldiers.

I have corresponded with Stan Karas Jr, son of Stan Karas,

second in command to Joseph Dawson. My next chapter,

Company G, is based on that correspondence.

In addition, I

have corresponded with Ron Streczyk, the son of Phillip Streczyk.

Mr. Streczyk has helped me understand his father's

accomplishments at D-Day. From what I gather, Phillip

Streczyk was nothing short of a one man wave of destruction.

In particular, Ron

Streczyk added a fascinating insight on one of the many unusual

stories about his father.

Sgt. Clarence Colson, himself a DSC

winner on D-Day, said this about Phillip Streczyk:

"I

remember Streczyk. I knew him all the way through. We had an

awful time keeping a helmet on him. He didn’t want to wear a

helmet.

In

Africa he snuck up around and somehow stole a German

motorcycle [Laughs] and came riding that thing into camp

[Laughs harder]. I remember that very distinctly. I can see him— brrrrrmmm— coming like a wildman.

We almost shot him. Good thing he didn't have a helmet on;

we recognized him at the last second and held our fire.

But, boy, he just

didn’t seem to care. Or he just figured the Good Lord was taking

care of him, I don’t know. Ordinarily, you’d keep your head down

and peek a little. You don’t just stick it out like robin,

shoot me, you know. I heard he was supposed to get the

Medal of Honor. They tried getting it for him. But anyway they

wouldn’t give it to him."

I would now like to offer Ron Streczyk's reminiscence

regarding Colson's anecdote. In June 2016 I received

this email from Mr. Streczyk.

June 28, 2016

Clarence

Colson speaks about "not seeing Streczyk for a coupla'

days".

When I was a

boy and my father was gone, one day I was watchingHogan's

Heroes was on the small screen, TV as we knew it.

My father had mentioned something about being POW.

Unsure what a POW was, I asked my mother about POWs and Dad.

My mother's

reply was, "Yeah, they took him prisoner a couple times.

Once for two days and once for one day."

Reading your

story about my father and coming across Colson's comment

jogged my memory. Colson concluded that my father

stole a German motorcycle. He would be correct about

that, but I believe he left something out. What

Colson probably did not realize was that my father [Streczyk]

was a captured POW for this two days absence and he

escaped.

Dad not only

escaped from enemy hands but he stole an equipped vehicle to

get away. The German soldier or soldiers in charge of

that vehicle most likely perished in the process.

Now the

question arises, what in hell was Dad doing away from allied

lines far enough to get himself captured?? One

possibility is that he was doing risky reconnaissance, no

easy task in the desert where there is no place to hide.

And that

incident took place right after he saw Christ. In my

father's own words, "We were in a foxhole, just me and

another guy for two, three days. Pinned down.

Bombs everywhere. I was so scared. We were

shitting in our helmets and throwing it out. I prayed

to god to let me out. That's when I saw Jesus and he

said, "You're going to make it out of this war OK."

Those were my father's own words.

Perhaps this

was the beginning of my father's blaze of glory.

Perhaps he felt courage born of a divine mission.

Please let me point out that my father saved far more enemy

lives that he took.

Ron

Streczyk

I cannot escape

the feeling that Phillip Streczyk's accomplishments during World

War II were far more profound than we will ever know. As

always, I tip my hat to this authentic American hero.

Captain Wozenski

Streczyk's greatest patron was Captain Capt. Edward Wozenski, the

colorful and highly respected commander of E Company. Captain

Wozenski was a hero in his own right. I found a great

story about a moment when Wozenski's E Company suddenly faced a

German tank attack. Wozenski let the German tank rumble over

his foxhole, then jumped up and blasted it with a bazooka from behind

all the while calmly shouting orders.

Whenever Wozenski spoke of the events of D-Day, Streczyk's name came up time

and time again. Wozenski was not only proud of Streczyk, I

think the older man was fond of him in a fatherly way.

On D-Day,

Wozenski's first encounter with Streczyk resulted in one

of the few humorous moments of the day.

There had been far too much death for

any laughter.

However, even the Grim Reaper might see the humor in this one.

Capt Wozenski was rushing to the top to find out what was going on up

there. By chance, Wozenski ran into Streczyk as he was coming

down to give the men on the beach the good news about what had just

happened at WN64.

Narration by Capt. Edward Wozenki, Commander of Company E:

"So I'm climbing the bluff to see what the hell is going on up there

and I met Sgt. Streczyk coming down. I see Streczyk is coming

down with a big grin on his face and I assume it's because he’s happy to see me.

Well, I'm happy to see him too. Maybe he can tell me what is

happening.

And I say, “My God!” as Streczyk puts his foot on a teller landmine

right in front of my nose. I can't believe it. I’m

climbing up the cliff and the damn fool puts his foot on a teller

mine! He's about to get blown to bits and the damn fool is going to

take me with him!

I get sick to my stomach with fear and think to myself, “Wha-? How stupid could you be?"

Streczyk sees the horror on my face and laughs. “Oh, don’t let

it worry you, Captain, it didn’t go off when I stepped on it going

up either.”

It takes me a while to start breathing again. The mine is a

dud and that sonofagun did this to me deliberately! I think

to myself, "That Streczyk, I'm gonna

break his neck the first chance I get.”

[RA Note: I ran across a footnote stating this

incident was included as a scene in The Longest Day.

So I looked up 'Streczyk' in the 1959 Cornelius Ryan book that the

movie was based on. While I was poking my nose into the book,

I just happened to run across an interesting tidbit.

There on page 265 was this sentence, "A

hundred yards away Sergeant Phillip Streczyk had his fill of being

pinned down too. Some soldiers recalled that Streczyk almost

booted men off the beach and up the mined headlands, where he

breached the enemy barbed wire."

Cornelius Ryan, the man who wrote the Longest Day, the most famous book about

D-Day, may have been the source of the Streczyk barbed wire

legend.

And who was Ryan probably interviewing when he heard

that story? Ed Wozenski. Wozenski's name appears in the

same paragraph. Therefore I think Wozenski is the person who

created the barbed wire misconception. However I don't think it was intentional.

That's just how Wozenski remembered it. Blame it on the fog of

war. Like I said, I think Wozenski was fond of Streczyk.

They weren't just acquaintances, they were friends. Besides, you know

how those Polish guys like to stick together.

Captain Wozenski had another favorite anecdote about Streczyk.

This is a great story.

On D-Day as he was riding to shore in his landing vehicle, Wozenski

was shocked at the number of men floating around in the waves with

their life vests on. At first Wozenski feared those were

airmen. He thought the 9th Tactical Air Force or possibly the

8th Air Force had taken a hell of a beating and these people had

gone in the drink. Then he figured it out. These weren't

air force guys. These were tank guys.

That meant the amphibious tank battalion that was supposed to hit the beach

four minutes prior to H-Hour had apparently failed. These men

in the water were

forced to escape their swamped tanks as the giant metal

contraptions sank

straight to the bottom of the English Channel. Wozenski

didn't know what had happened at the time, but he cursed anyway.

Wozenski

knew enough to know if the tank men were in the water, then the

tanks weren't on the beach. This was not a good sign for the attack.

Sure enough, when Wozenski got to the beach, he saw only two tanks there

- both quickly disabled by German fire.

That confirmed his worst fear. He assumed this meant the other

62 DD amphibious tanks had sunk and the crews bailed out.

Wozenski also noticed there were no holes (bomb craters) on the beach for the men to hide in.

That meant the bombing attack had failed too. Wozenski was furious,

but reserved most of his anger for the tanks. It was one thing for the bombers to miss

their targets due to lack of visibility, but those swimming tanks were

supposed to be a sure thing.

He thought to himself, 'Those goddamned tanks were supposed to be the focal point of the entire attack. This

is

a disaster!!'

Wozenski groaned at the irony of it. These floating

tanks were

supposed to be the great secret weapon of the day. The

security surrounding these tanks during the build-up to D-Day was

practically as tight as the highly classified secret of the

Normandy landing location

itself. And now the entire tank force was in the drink.

How ridiculous.

Wozenski recalled, "We were all so secretive, sworn to such secrecy,

about these famous "DD tanks". Everyone knew those tanks were

terrible! They were supposed to be these incredible tanks, but

they performed so badly in tests we called them 'Donald Ducks'.

We pleaded with the tank guys to use the British model, the Hobart

Funnies, because they were proven to be successful in combat, but

they didn't listen to a thing we said. Those idiots almost

cost us the invasion.

So now here we are in Normandy, the day after

the attack, and Sergeant Streczyk, what a sense of humor that man

had, calls me over for a look-see into a bunker. The guy has a

grin a mile wide. I frowned. Uh oh, here we go again. Now what? Was he

going to fake blowing us both to pieces again?

So he drags me inside this massive bunker and points. There on the

wall the damn Germans had painted a picture of one of our precious

secret Donald Duck tanks just so they would recognize it. The painting was so pretty it reminded me

of a Betty Grable pin-up! I am surprised they didn't add a big

bosomed Fraulein sitting on the muzzle with a big smile on her face. Heck, that's what our guys would have done. Good Lord, the Jerries had known about our vaunted secret weapon the whole time!

All that secrecy! [Laughs] Streczyk and I howled over that one.

Those idiot tank guys didn't have a clue what they were doing."

In the same interview,

Wozenski went on to make his famous quote about

Streczyk:

"I think that

Streczyk’s

the greatest unsung hero of World War II. That's right, Sergeant

Streczyk, one of my platoon sergeants. Because he was the first

one off the beach. To the best of my knowledge, he was the first

one off the beach and it was the path that he took that I picked

up. The rest of our battalion followed, 2nd Battalion 16th

Infantry, and then later on I think almost the whole corps went

up that path."

Wozenski later went on

to say this:

"If Streczyk did

not earn a Medal of Honor, no one ever did. Thousands of men

were on the beach being killed like flies. To even lift your

head over the shingle was to invite quick death. Yet Streczyk

led a small group up the bluffs, cleaned out enemy pillboxes,

and released a flare to indicate his breakthrough, which the

others followed."

(source: Omaha Beach, Joseph Balkoski, pg 204)

The Legend of Sergeant

Streczyk didn't end there. Sgt. Walter Bieder told this

story:

"Two weeks after

D-Day, it was time to move out. It was a mess out there.

We passed

St. Lô. I looked at it in horror.

St. Lô was just about leveled to the ground by our aerial bombing. There wasn't

much left.

[Note: St. Lô was a town 20 miles from Omaha that was

the scene of fierce bombing. St. Lô was at the junction of

two important crossroads; the Allies bombed it to limit German

troop movements.]

The Germans were always threatening a Blitzkreig. Well,

St. Lô, damn, that was a Blitzkreig of our very own right there.

After we were finished with that spot, I think they had to build a

brand new St. Lô. The place was flattened!

The German Seventh Army was retreating and our planes were dive

bombing them and strafing them, tearing the Nazis up to hell.

We were on the move to cut off their retreat. At a town

called Mons, the

Krauts were on one road and we were over here. And

eventually we met.

Our platoon got up to a brick wall around a cemetery. The

Germans were in there surrounded. They were running around wild down there and the guys were

picking them off. Man, those guys were running. A couple of my men

said, “Fifty bucks I nail that son of a b—.”

Streczyk wasn't happy about shooting the Krauts cold-blooded like

that, so he decided to do something about it. Streczyk and

somebody else grabbed a jeep and drove it with a white flag into German lines.

Streczyk starts up with that Polish lingo again and

talked a bunch of Germans into surrendering. And they came

in by the hundreds. Hundreds of them! The

turkey shoot was over.

Streczyk

saved their lives. No doubt about it. We teased

Streczyk and called him "Sgt. York" for capturing the whole damn

German army by himself.

[Note: Sergeant York was the most

famous hero of WW I. One of the final scenes of the 1941 movie

about York shows him and a handful of other survivors trudging

back to American lines with 132 German prisoners in tow.]

|

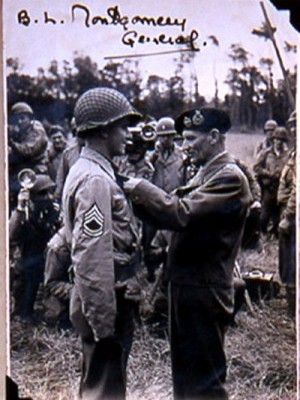

For Streczyk's

exploits on D-Day, he was

awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Be

sure to note

there is no mention of the disputed barbed wire incident.

Streczyk

was also honored with the British Military Medal, pinned on by General

Montgomery himself.

Streczyk's citation

states:

“For gallantry in

action against the enemy on 6 June 1944 near Colleville-sur-Mer,

France. T/Sgt. Streczyk was one of the first men to enter

the maze of trenches and dugouts in an enemy stronghold.

In desperate hand to hand fighting, Sgt. Streczyk cleared out

compartment after compartment. In this fighting he

captured an officer and 20 enemy soldiers. He then, with

complete disregard for his own safety and without assistance,

assaulted and destroyed an enemy machine gun nest.

The

heroic and courageous actions of T/Sgt. Streczyk were in keeping

with the highest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United

States.”

|

I think it is safe

to say that Streczyk was an

incredible hero. No, he probably didn't cut

the barbed wire. But I don't think that matters one bit.

Streczyk was the point man who led the amazing attack on

WN 64.

Badly outnumbered, the Americans dismantled

WN 64

one unit at a time.

Streczyk risked his life repeatedly as he led

each attack. Much of it was face to face combat in trenches... very

dangerous stuff. A well-thrown grenade or a hidden gunner

could mean instant death.

For Streczyk’s

amazing bravery that day and throughout the

entire war,

I hope someday Phillip Streczyk will receive the Congressional Medal of

Honor. He gets my vote.

And

I know just how to get Streczyk that award - make a movie about him. I would pay to see

that movie. I bet you would too.

|

|

|

Reflections

on D-Day

An Excerpt from

Omaha Beach: D-Day

Written by Joseph Balkoski

pg 168

No historical account can honestly classify any outfit that

landed on Omaha Beach on the morning of June 6 as "lucky".

Some units, however, may be defined as "less unfortunate" than

others.

Among those that may be

consigned to that category are Lt. John Spalding's boat team from

Company E and Capt Joseph Dawson's Company G, both of the 16th

Infantry.

Spalding's team had come

ashore shortly after H-Hour at a point halfway between the St.

Laurent and Colleville draws virtually alone.

About 20 minutes later,

Dawson's company followed in its wake. Although both groups

met heavy fire crossing the tidal flat, both companies managed to

reach the line of shingle rock at the high-water mark relatively

intact.

Here they had by chance

stumbled into a position where they were separated from German

strongpoints by a greater distance than any other 1st Division unit

that had yet landed - more than 500 yards.

Additionally, Spalding

and Dawson's men were partially shielded from enemy observation by

three decrepit stone cottages situated just beyond the shingle,

wrapped on two sides by sturdy stone walls several feet high.

From this place,

Spalding and Dawson were among the first Americans on Omaha Beach to

arrive at the unanticipated conclusion that the only way off the

beach would be over the bluffs, not straight through the beach exits

as the invasion plan had specified.

|

|

Into the

Teeth of the Defense

"Spalding

and Dawson were ... the first... to arrive at the

unanticipated conclusion that the only way off the beach

would be over the bluffs, not straight through the beach exits

as the invasion plan had specified."

Rick Archer's Note: I sat straight up in my chair when

I read that sentence!

I read over 30 different accounts of D-Day in preparation

for this article and Mr. Balkoski was the only person to directly point out

that the pre-invasion strategy was to attack the draws, i.e. the

gaps between the hills that were defended by strongholds on EITHER

SIDE. When I read this, my mouth literally dropped open.

So I started to review the other sources with a more discerning eye; sure enough, Balkoski was

right.

"the draws, the

natural exits off the beaches, were the main targets in the

initial assault plan. However, the strongly concentrated

defenses around these draws meant that the troops landing near

them quickly wound up in no shape to carry on a further assault.

Only in the areas between the draws, at the bluffs, were units

able to land in greater strength. Defenses were also weaker away

from the draws, thus, most advances were made there.

[Army

Military History]

Rommel built his entire defense around those strong points.

What military genius devised the plan to send our American troops

directly at them? Heinrich Severloh, the infamous Beast

of Omaha, killed 1,000 Americans singlehandedly. And how did

he do it? If I am reading this correctly, the answer seems to

suggest that our military strategy dictated our men would run

straight at the defenses

guarding a draw without any kind of protection!

"...the troops landing near them quickly wound up in no shape to carry

on a further assault".

That certainly is a

nice way to put it. I would call it 'senseless slaughter'.

I suppose it is always easier to criticize and hindsight is 20-20

and all the other clichés, but the one thing that has always

disgusted me about Omaha Beach was the stupidity of sending

those men into battle so totally defenseless. Now I am to understand they

were not only sent in defenseless, but they were deliberately sent into the

teeth of the defense as well! I can't seem to shake the image

of a bunch of smug military planners sitting at their comfortable

table drinking tea while they bandied about dry statistics of casualty

probabilities. These kids should not have been treated like

expendable toy soldiers or like plastic cubes in a game of Risk.

It makes me furious. By sending these young men into the teeth

of the defense, they were given little or no chance of survival.

I can certainly sympathize with Ed Wozenski, the commander who broke

down in sobs that night when he discovered he had lost 140 of his

200 men in battle that day. He felt a helpless rage that lofty

predictions of bomb craters on the beach to hide in and powerful

tanks to hide behind had been empty promises.

There cannot be any question of the bravery of the American soldiers

that day. I have little doubt that every single one of them

was scared out of their wits, but they tried their best anyway. As Patton pointed out, "courage is not the absence of fear, but rather

the ability to act in spite of fear." By that standard, our

men performed admirably.

Unfortunately - and trust me, I don't like saying this - it is my

impression that the men who planned this attack failed miserably.

The utter cluelessness of the planners was impossible to overlook.

There was little finesse; it was all brute force - "Send 10 men

straight at a machine gun and hope that one gets off a lucky shot

before he is mowed down".

If there is one book on Omaha Beach to read, I would recommend Mr.

Balkoski's Omaha Beach. He really seems to 'get it'.

Not only does Mr. Balkoski get it, so do the readers of his book.

I would like to share this review of Balkoski's

Omaha Beach from one of his readers.

"There are three

things I take away from Balkoski's

account.

One is the

remarkable resiliency, courage and resourcefulness of the

troops.

The other was

the pervasive constant foreboding the

planners must have felt that the Germans

would surely counter-attack

with the Panzers and push them off the beach before it was

secured. That fear can be the only

possible explanation for the many foolhardy risks taken.

Someone - thank

goodness we will never know who they were - sent those brave young men

straight to their death on one senseless 'Mission Impossible'

after another. In the movies those kind of missions always

succeed with only the nastiest person killed to convey 'realism'.

Nonsense. In reality those missions usually fail. On

Omaha, they all failed.

It is amazing

to me that the USA got the job done with so many mistakes. It was

basically sacrificing American lives.

Sixty-five years after the fact, Balkoski's book is a stark reminder

that to the soldiers on the beach the final outcome of this

assault was far from pre-ordained."

|

Improvisation

Rick

Archer's Note:

As we have read, credit for

the

initial turning of the tide of D-Day

goes to the work

of three men - Lieutenant John Spalding,

Sergeant Phillip Streczyk, and Captain Joe Dawson

- plus of course the brave men in their companies who participated in the raids.

Spalding, Streczyk, and Dawson were hardly the only the men to risk

their lives in the service of their country on D-Day. Nor were

they the only heroes.

There were many American heroes at Omaha on D-Day. I read several amazing stories

about

how the soldiers tried to assault the powerful WN strongholds defending the four "Gaps".

However, a case can be made that these three

men made the single most

important contribution of the day. They were the first to

reach the top and they were the first to take

out a strong point. Once

WN64

went down, suddenly it became safe to land on the beach for the

first time all day. The Americans poured everything into this

breach and gained the initiative.

One thing that I have not made clear enough is that Spalding and

Dawson were successful because they improvised the plan of attack.

They were told the entire point of the attack was to go directly

after the strongholds. Instead, once they landed, both men had

the sense to see the futility of that plan. Instead they took

their men straight up the hill even though it wasn't in their orders

to do so. As it turned out, this action led Spalding to

successfully take down a

WN

stronghold by coming in from the rear. Both men deserve credit

for their leadership skills and their common sense. And

Sgt Streczyk, of course, deserves credit for executing Spalding's

plans so brilliantly.

There is a distinct possibility that Rommel was the superior of all

the Generals on the field that day. His brilliant defenses

gave his small defensive force enough leverage to keep a vast attack

at bay. Who knows, had he been given another month or so to prepare and

more men to defend with, I might be typing in German now. Ach du lieber!

But there can be no question that the American fighting men were far

tougher than their German counterparts that day. I read accounts of

Germans surrendering or fleeing time and again. There wasn't a

whole lot of laying down lives for the Führer. On the other

hand, constantly defying death,

the Americans kept coming. At first, the American spirit was

broken. Then Dawson and Spalding made the difference. By

creating the first breakthrough, their success gave courage to

everyone else. After that, the Americans clearly became

the more determined fighting force. American military planning

wasn't very good, but we had great leadership on the beach.

Dawson and Spalding were just two of the many fine leaders I read

about who made the difference.

Streczyk, Spalding, and Dawson were the stars of the day.

Through

their courageous individual efforts as well as

the brilliant teamwork

of the soldiers they led up the hill,

these three highly decorated men were the

ones responsible for creating the first real breakthrough of the

day. They helped turn a losing effort

at Omaha into a miraculous comeback

victory for the Americans.

They saved countless lives of the men trapped on

the beach in the process.

Credit and the

Tendency to Generalize

Changing the subject a bit, I

could not possibly have done this much research without forming some

personal

impressions about the men I studied.

One thing I gathered from the comments of the men in Spalding's

platoon was that to a man they had nothing but admiration for

Phil Streczyk. These men said so much about Streczyk's initiative

and intrepid nature that I

could not help but get the impression that Streczyk was the unspoken

leader of the platoon at D-Day. There is a good chance

that Streczyk thought the same thing, but I won't pry that door open too

wide.

I also felt John Spalding quietly agreed that Streczyk was the main

reason for the platoon's success. As I read Spalding's Interview, he seemed to rely on

Streczyk at every turn. However, let's give Spalding some

credit here. Okay, this is Spalding's first action.

Rather than be some pompous fool, he had the sense to put his ego

aside and rely heavily on his experienced second-in-command.

That simply makes me respect Spalding more.

It seemed like the two men

complemented each other well. I got the sense that Spalding

was an intelligent and capable leader while Streczyk was the

impetuous man of action. When it came time to attack the

WN 64

fortress, Spalding sized up the best plan of attack, then took a

step back and let Streczyk go to work. Fire and Ice... pretty

good combination.

I am not trying to cause trouble here. Spalding did as well as

he could under the circumstances. However, at D-Day,

John Spalding was a young and very green Lieutenant.

Spalding must have done something right or

he wouldn't have been given the DSC. But I am just pointing out

that Streczyk was a veteran who had already earned the complete

respect of the men. It is to Streczyk's credit that he

seemed to support Lieutenant Spalding in every way he could in the

field. However... and forgive me if I step on someone's toes

here... I do have a lingering hunch that Streczyk had no problem

singing his own praises after the battle is over. And you know what?

I don't blame him a bit. Unless the true story has somehow

been obscured, from what I read Streczyk took most of the risks.

Therefore he

should get the lion's share of the credit.

And this brings up an interesting point. Who deserves the

credit? Who gets the credit? Does the credit always get

placed where it belongs?

There is an innate

human tendency to generalize. I am as guilty as the rest.

There were so many details in the D-Day story that it was usually easier

for me to say, "Spalding did this" or "Dawson did that". The

truth is that sometimes it was really Streczyk who did it. Or

Colson. Or Colwell. Or Bieder. Or

DiGaetano.

One

writer flat out stated, "I get the feeling that the writing of this

tale gives far too much credit to the leaders. The real heroes

were the men who did the fighting."

Isn't that the way it always is? There are ten other men

blocking for the Quarterback, but Elway, Manning, and Brady get the

headlines. There were two other Supremes besides Diana

Ross, but few people can name them today. Try naming the other

two guys on Neil Armstrong's trip to the moon.

Will

Spalding and

Dawson's names will go down in history? Or Streczyk?

Right now, I doubt that very few people have ever heard of any of

the three men. I certainly did not know who they were until I began

nosing around the story of Omaha Beach.

Someday that Viewing

Platform next to the Cemetery might just have a statue of Spalding

and Dawson.

Or perhaps someone

will name the bluffs on either

side of the Platform for them. That would be a nice gesture.

And easy to do as well. Why not a plaque in the exact area

where they reached the top for the first time? It would a

fascinating piece of history for all the visitors to learn.

But what about Streczyk? Does he get a statue too?

Or does he get the spare wheel treatment because he was merely a

sergeant?

I think it would be a

perfect gesture to honor Dawson and Spalding at the Platform, but if it means overlooking someone like

Streczyk, then, yes, I would have a big problem with that. It is a shame

when the Fighting Men don't always get the credit they deserve.

If you come away from this story with one memory, it might be that a

three-headed superhero named Dawson-Spalding-Streczyk won the

Battle. That is a perfect example of our need to 'generalize'.

Who can remember all the names? There were thirteen

WN

resistance nests on Omaha Beach alone. The conquest of every single stronghold

carried its own remarkable story. For example, on the other

side of the E-1 Draw, just 200 yards

across the draw from the

WN 64

stronghold that Spalding's men took out, there was a pitched battle led by two heroes named Gibbs and Skiba for control of stronghold

WN 65.

It was a great story, but I figured telling it would water down

the story of the initial penetration of the day.

Furthermore, just down the road to the east, there was a remarkable story of the

attack on WN

61

led by Raymond Strojny.

And what about what Jimmie Montieth did at

WN60? Or Walter

Taylor? Or Frank Peregory? Or William Williams?

There were four Medal of Honor winners from Omaha on D-Day.

Jimmie Monteith was one of them. He risked his life six or

seven different times leading a direct assault on strong point

WN60.

As you read the account, Monteith almost succeeded in taking the

fortress down by himself. He died in the process.

Carlton Barrett saved the lives of at least a dozen men by

dragging them to safety after they had been shot on the beach.

The point is that Barrett was being shot at in the process. He

risked his own life so many different times to save the life of others.

John Pinder

was a radio technician who refused to take cover when he lost his

equipment during the melee on the beach. He was wounded, but

went back into the water to retrieve his equipment. He was hit

again bringing it back, but hauled his equipment to shore and set up shop.

Bleeding and in great pain the entire time, Pinder relayed valuable messages to his

commanders until a third wound cost him his life.

Theodore

Roosevelt Jr, the son of President Teddy Roosevelt, did a

fabulous job managing the incredibly successful attack at Utah

Beach. He was the only General to actually risk his life and

go in with the first wave. The rest of the Generals

stayed on the ships.

Have you ever heard of any of these men? Many of you

probably remember Roosevelt from The Longest Day

movie... Henry Fonda did a terrific job of portraying Roosevelt's

courage in the movie. Consequently, before I began my research,

the Roosevelt/Fonda character was the only name

I remembered from the movie. But as for Monteith, Barrett, and

Pinder, I had never heard of them in my life. And guess what?

Not one of those brave heroes got their names or stories told in the classic D-Day book The Longest Day.

It is tough giving enough credit to everyone.

This story is just too big and there were too many heroes that day.

My little list barely scratches the surface.

The human mind just can't keep

track of all the stories. There are a lot of people in this

war who deserved credit, but didn't get it for this simple reason.

In a way, it is a shame that Spalding and Dawson get all the credit,

but that's the way it is.

Oh, by the way, did you notice I just omitted Streczyk's name?

That is because I am wrapping things up and it's time to generalize.

Every time someone generalizes, another name gets dropped off the

list. Streczyk was the leader, but he wasn't the Captain.

In the scheme of things, credit goes to Spalding, the preppy college

boy. When you see a map of D-Day, it says, "Spalding's Movements".

I don't recall one example of Spalding firing his weapon while

Streczyk risked his life time and again. But it says

"Spalding's Movements". Is that fair? No. Is that the way it is? Yes.

Tough luck, Streczyk. Too bad you didn't go to college. Now go away and be forgotten.

Maybe at the next cut, Spalding and Dawson are gone too.

Sometimes I wonder where the word "Generalize" comes from. In

the end, it was the General who got all the credit. Eisenhower

is the only name most people can mention. And he didn't fire a shot. He

didn't even step foot on Omaha that day. And yet 60, 70 years

later, Eisenhower remains as the only name linked to D-Day for most

people.

Isn't it funny how credit works?

|

|

The Three

Leaders of the Breakthrough

|

Captain Joe Dawson

being awarded

the DSC by General Eisenhower

|

Sergeant Phillip

Streczyk |

Streczyk

being awarded the British DSO by

General Montgomery |

Lt John Spalding

being awarded

the DSC by General Eisenhower |

And now one last look at our heroes.

I couldn't help but peek

a bit into the lives of our three heroes beyond the war. Each

of the men has a Wikipedia listing, but there isn't much to read

about other than a brief summary of their service record.

Despite the lack of "after the war" information about the men, I

was able to find a few tidbits.

John Spalding is the biggest mystery. I found next to

nothing about him on the Internet.

From what I read, Spalding was injured in the fighting that

took place in the French countryside shortly after D-Day. I was unable to track

down a single detail of the incident, but I do know it wasn't

serious. On the other hand, I did not see his name reappear in

the story of E Company at the battle of Hürtgen Forest, so there is

a chance the injury ended his fighting for the war.

John Spalding was a native of Owensboro, Kentucky. After the war, he

returned there and served two terms in the Kentucky House of

Representatives. He died in 1959.

There is an excellent "Homecoming"

article about John Spalding on the War Chronicle website.

This picture shows Spalding in the hospital with an Army chaplain as

he is recovering from his wounds.

|

|

|

Phil Streczyk saw action in five other major battles during WWII

with the "Big Red One", including Tunisia, Sicily, and Hürtgen.

He was awarded the Silver Star four times. From what I gather,

Streczyk was greatly admired for his fighting skill and his courage.

He was even more admired for his preference to take prisoners alive

than kill Germans outright.

Strecyk suffered a mental breakdown in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest

from intense battle fatigue. Without any warning, Streczyk

fell to pieces and had to be helped off the battlefield. The

constant stress became too much.

When

I read this, I couldn't help but start to cry in sympathy. Why

didn't someone see the signs and try to help him? Our heroes

aren't supposed to have weaknesses, but we are all human.

Every man has a breaking point, even this courageous warrior.

Every time Streczyk helped win another battle, his reward was to get

sent back into action. Hey buddy, get out there and stick out

your neck some more. It all finally caught up with him.

I had never even heard of the Battle of Hürtgen Forest until I read

Streczyk's story. Situated just east of the border between

Belgium and Germany, The Battle of Hürtgen Forest took place from

September 1944 through February 1945. This six-month battle was not only the

longest battle on German ground during World War II, it was the

longest single battle the U.S. Army has ever fought in its history.

|

The Hürtgen Forest cost the U.S. 1st Army at least 33,000 killed and

incapacitated, including both combat and noncombat losses; Germans

casualties were 28,000. Hürtgen was so costly that it has

been called an Allied "defeat of the first magnitude".

I read that Streczyk was haunted by memories of the war for the rest

of his life. Reading that broke my heart. If anything,

this news only served to increase my deep admiration for the man.

Prevention of Loss From Psychiatric

Disorders Related to War

"Just as an

average truck wears out after a certain number of miles it

appears that the soldiers wore out, either developing an acute

incapacitating neurosis or else becoming hypersensitive to shell

fire, so overly cautious and jittery, that he was ineffective

and demoralizing to the newer men. The average point at which

this occurred appears to have been in the region of 200 to 240

regimental combat days."

The first page of the Surgeon General's report, dated 16

September 1944.

Another American hero from World War II, Audie Murphy, suffered from

the exact same problem. Murphy was reportedly plagued by

insomnia, bouts of depression, and nightmares related to his

numerous battles throughout his life. His first wife, Wanda Hendrix,

often talked of his struggle with this condition. His problem

was so serious that one night Murphy held her at gunpoint during one of

his spells.

Beyond his war accomplishments, Audie Murphy is to be commended as a

great human being for two reasons.

For a time during the mid-1960s, he became dependent on

doctor-prescribed sleeping pills. When he recognized that he

had become addicted to the drug, he locked himself in a motel room

where he took himself off the pills, going through withdrawal for a

week. For anyone who understands chemical dependency, that was

an amazing accomplishment. It is amazing to go cold turkey on

one's own.

Murphy is also to be commended for breaking the taboo about publicly

discussing war-related mental conditions. In an effort to draw

attention to the problems of returning Korean and Vietnam War

veterans, Murphy spoke out candidly about his own problems with

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Considering it was said to be

'shameful' to discuss such problems, Murphy was a hero again for

having the guts to bring the problem out in the open and face public

ridicule. In the public mind, our heroes are not supposed to

have weakness. They are supposed to be brave, face

death, kill men, watch them die in agony, and then come home and be

cool about it. But in the real world, it doesn't work that way.

In my book, Murphy was a hero again for putting his movie star

reputation on the line to come to the aid of the returning fighting

men.

There doesn't seem to be an easy solution either. Today's news

continues to report the same problems with veterans returning from

Iraq and Afghanistan. Families are torn apart repeatedly by

war-scarred veterans who can't seem to adjust back to life in

Pleasant Valley and Happy Hill. War is hell and the human

spirit doesn't cope with it very well.

Phillip Streczyk is a native of East Brunswick Township, New Jersey.

Streczyk died a hero back here in America. It is a shame that

the war followed him home. Streczyk is survived by his

daughter Phyllis and son Ron.

There is an excellent "Homecoming"

article about Phil Streczyk on the War Chronicle website.

It should be obvious that

I developed a tremendous admiration for Joseph Dawson.

I

thought it was interesting that

Dawson enlisted in 1941 as a private. In the years prior to

D-Day, Dawson had fought earlier campaigns in

Africa and Sicily.

Obviously someone recognized the talent in this man, because he was

systematically promoted all the way from private to Captain. Before D-Day, Dawson served as a staff officer in

the First Division and the 16th Regiment during the campaigns in

North Africa and Sicily.

I was surprised to find out that his accomplishments at Omaha Beach

were secondary to what he did afterwards. After his service in Normandy, Dawson continued to serve as

commander of G Company throughout the campaign in France, Belgium

and, finally, to Aachen, Germany where he took part in the Battle Hürtgen

Forest.

During the battle for Aachen, Dawson's G Company (along with I Company) held off German

counterattacks for thirty-nine days.

During the battle, the spot that Dawson and his men defended became

known as "Dawson's Ridge". Apparently the name stuck.

Today the same spot is still referred to as 'Dawson's Ridge' in U.S.

Army history. This ridge sat astride the main route that for the German attempts

to relieve the city of Aachen, which Hitler had ordered to be

defended at all costs. G Company lost 117 out of 139 men

during the battle for "Dawson's Ridge." For this action, Dawson's command was honored with the

Presidential Unit Citation.

|

|

Some people might refer to Dawson as a born hero. He performed

his duties at every point of his military career with excellence.

Everyone seemed to notice how sharp he was. For example,

the unnamed US Army historical

officer who interviewed him in August 1944 two months after D-Day noted

in the margin of Dawson's report on Company G's D-Day activities, "This man is an unusually

accurate witness."

Let me add that the memorial to Dawson that I saw at the Visitor's

Center led off with one word - Competence. Definitely!

As I reviewed Dawson's

activities during D-Day, I noticed Dawson's deep concern for his

men showed through repeatedly. Early in the morning, Dawson chose to climb 'Breakthrough

Alley' with just a couple men to scout for enemy positions. He

assumed that a small group of men would be harder to see and harder

to hit. Dawson did not want to expose his company to extreme

danger needlessly... so instead he took on the risk himself.

That kind of leadership is impressive.

Later in the day as Dawson and his men desperately clung to their

position in the village of Colleville against a determined German

counter-attack, Dawson was appalled when his own navy began bombing

the position at 1600. Like the naval bombing which had not

accomplished a damn thing that morning, this renewed bombing attack

only succeeded in killing many of his own men. Dawson was

incensed at the carelessness of the Navy to begin a bombing campaign

without learning first of the conditions at the bomb site.

Dawson was a leader who cared deeply about his men. I admire

him.

|

|

I was also continually struck by Dawson's modesty. Dawson never

failed to give credit to his men for their success. If you

read his interview, you would think he was smoking a pipe the entire

day. Then you hit yourself over the head and remember that he

singlehandedly took out a machine gun nest that was about to mow

down his men as they came up 'Breakthrough Alley'. Then you

remember he took out the enemy at a church in Colleville with only

two other men to help him, one of whom died in the fighting.

Dawson fought just as hard as his men, but he had a way of

deflecting the credit towards them.

Dawson's innate modesty showed up again years later in a very unusual

way. Apparently there was a growing debate over which company

made it to the ridge first - Company E (Spalding) or Company G

(Dawson).

As I read the various reports, there was some circumstantial evidence to

suggest Dawson got to the top first, not Spalding and not Streczyk

who gave all the interviews. There was a question that

perhaps a delay at a mine field allowed Dawson to pass Spalding's men

a couple hundred yards away on another part of Breakthrough Alley.

After Dawson took out the machine gun nest, that would have made it

safer for Spalding's men to move up as well.

This is all circumstantial, by the way, but it clears up at least

one mystery. There was a reference made by the Polish machine gunner

interviewed by Streczyk to 16 Germans in a trench nearby.

Spalding asked Company G to give supporting fire while he and his

men cautiously approached the trench. The trench was

completely abandoned. Why? One possible explanation was

that Dawson's men had been through there already and given the

Germans a good reason to retreat. Which raises another

question. Why was Company G conveniently there in the first

place to give support to Company E as they searched for the 16

Germans in the trench?

So who really got to the top first? I don't know the

truth nor do I care. What difference does it make?

They were all heroes that day.

However the historians were starting to make a fuss.

Apparently there was a growing controversy over which man made it to

the top first - was it Spalding or Dawson? Fifty years

after the battle, the famous D-Day historian Stephen Ambrose wrote a

letter to Dawson to get Dawson's first-hand opinion.

In response, Joseph Dawson

wrote a wonderful tribute

towards John Spalding. The former

G Company captain wrote this:

"I feel,

Dr. Ambrose, that all honor and tribute should be given

to Lt. Spalding and his small group of men and to the

men of my own G Company 16th Infantry, for they formed the

spearhead that through luck, courage, and proficiency

opened the one breach in the enemy's defenses that led

to the winning of the battle of Omaha Beach."

How classy is that? Dawson

not only saluted the accomplishments of Spalding and his men, but to

his own G company men as well. Except that he left out one

thing - any mention of himself. Joseph Dawson was not

only intelligent and brave, he was also an incredibly modest and

decent

individual.

Speaking of

'intelligence', the US Army put Dawson to good use after the war.

After his detachment from the 16th Infantry, Dawson served in the

Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.) for several years.

According to Wikipedia, Dawson married Melba Bruno in 1946, very

likely

while he served in the OSS. They

raised two children, Roslyn and Diane. The Dawson family lived in

Corpus Christi, Texas, and in Denver, Colorado. In civilian life

Dawson

was a geologist in the oil industry. An elementary school in Corpus

Christi, Texas, is named in his honor.

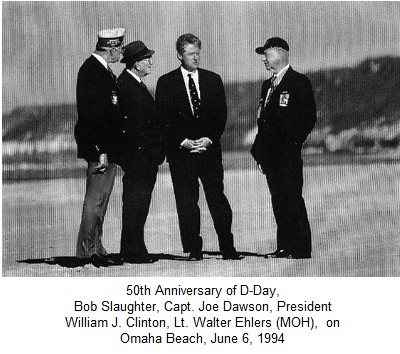

In June 1994, Dawson revisited Normandy to introduce President Bill

Clinton during ceremonies marking the 50th anniversary of the

invasion. Sadly, he passed away four years later in 1998.

|

Death

of a Hero:

Joe Dawson dies at 84

Naming of school for oilman was most recent of

his many honors

Wednesday, Dec. 2, 1998

By

SARA FERNANDEZ

Staff Writer

Retired Army Maj. Joseph Turner Dawson, decorated World War II hero

who opened a path off the beach at Normandy, independent oil

operator and community leader, died Saturday. He was 84.

"Joe is a hero, he's my hero," said Corpus Christi lawyer Jim Wray,

who worked for the city attorney's office when Dawson was a City

Council member.

"He was the kind of fella that you would expect. . . . There was a

steely part of his character but he was also a very cultured man,"

said Wray, a Navy veteran who like Dawson was at the invasion of

Normandy.

"He served very gallantly, returning a hero from World War II," said

Abel Chapa, Nueces County veterans service officer. "He was a grand

fella. He leaves quite a legacy."

Dawson's

Exploits

Dawson's legacy extends from the beaches of Normandy, where his

heroism earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, to a Corpus

Christi elementary school.

Dawson, a geologist who worked for Humble Oil Corp. and Renwar Oil

Corp. before becoming an independent oil operator, kept a tradition

of service in his civilian life.

He served on the Corpus Christi City Council from 1947 to 1949. He

later served as chairman of the Civil Service Commission and as a

member of the Arts Commission and the Planning Commission. He also

was chairman of the Corpus Christi Red Cross, chairman of the Corpus

Christi Heart Association, and as president of the Reserve Officers

Association of Corpus Christi.

He was one of the founders and served as vice chairman of the board

of the University of Corpus Christi, now Texas A&M University-Corpus

Christi.

School honors Dawson

His name continues to be connected with education. In 1997, Corpus

Christi Independent School District opened the Joseph T. Dawson

Elementary School.

When the school was named for him, Dawson told the Caller-Times he

was especially honored that through the school he would leave a

legacy for the youths of the city he loved.

But he'll be remembered for much more.

"He was one of the real heroes, many people don't realize what he

has done and what he meant to this city as far as a role model,"

said Mayor Loyd Neal, who met Dawson through veterans organizations

and efforts to protect area military bases from closure.

"He was very unassuming," Neal said.

"If you didn't know Joe Dawson's story ahead

of time, you weren't going to get it

from Joe Dawson."

Omaha Beach landing

On June 6, 1944, Capt. Dawson, who enlisted in 1941 as a private,

led the first troops from the slaughter on Omaha Beach. Dawson

landed at Omaha Beach with the 1st Infantry Division -- "The Big Red

One" -- and he and his men moved against fierce German fire.

The 30-year-old spotted the first path from the beach and by the end

of the day's battle his troops were the farthest inland of all the

Americans.

About a month later Dawson received the Distinguished Service Cross

from Gen. Dwight Eisenhower for his actions on D-Day.

His heroic exploits continued throughout the war. Outside Paris,

Dawson rescued a platoon of men separated from his company and

ambushed by the enemy. He was awarded the Silver Star for bravery in

the battle that liberated Paris.

Later that same year Dawson's G Company and I Company defended a

vital ridge overlooking the city of Aachen, Germany, for 39 days

against large German forces. The men received the Presidential

Citation and the spot is now known as "Dawson's Ridge."

Medals and honors

Dawson, who retired in 1946 as a major, was also awarded the Bronze

Star, Purple Heart with oak leaf cluster, the Combat Infantryman's

Badge, beachhead arrows for the North Africa, Sicily and France

landings; unit honors earned by the First Division and the 16th

Regiment, campaign medals for the European theater; and the American

Defense medal.

"He wasn't a person that looked for honors but he was just an

honorable person," said Ram Chavez, commander of the Alaniz-Valentine

chapter of the Military Order of the Purple Heart and director of

the Veterans Band of Corpus Christi.

"To see him speak . . . the emotion he had for the men that served

under him. . . . He could talk about them and you could see that

even 50 years later he still felt the same about them," Chavez said.

In 1984, the Army authorized citing Distinguished Members of the

16th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division, and Dawson was among the

first five. Dawson also was inducted into the Officer Candidate

School Hall of Fame at Fort Benning, Ga.

|

Dawson Introduced the

President

On June 6, 1994, at the 50th anniversary of D-Day,

Joe Dawson

introduced President Clinton. This came during a memorial ceremony in Normandy.

During the ceremonies Gen. John

Shalikashvili, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, lauded Dawson

for his contribution during WWII.

". . . When history books are

written about the great invasion of France, you may not

necessarily read of Joe Dawson, but no history will

ever be complete without him."

Dawson is survived by two daughters, Diane

Dawson Delk of Houston and Roslyn Randolph Dawson of Dallas.

Rick Archer's Note:

I

think Joseph Dawson was more than just a war hero. This man

was a classy, dignified leader in all walks of life. We should be grateful that America had men

like him to fight for his country. In our pantheon of heroes,

Mr. Dawson belongs among the greatest of World War II.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Before I forget,

I would like to acknowledge the gifted work of the men and women who

have invested so much of themselves to help tell the story of our

brave men of Omaha.

Reference 1:

War Chronicle

Reference 2:

Spalding Interview

Reference 3: The Fighting First - Flint

Whitlock