Part 7 -

More Heroes of D-Day

Story written by Rick

Archer

|

|

Captain Joe Dawson

being awarded

the DSC by General Eisenhower

|

Sergeant Phillip

Streczyk |

Streczyk

being awarded the British DSO by

General Montgomery |

Lt John Spalding

being awarded

the DSC by General Eisenhower |

|

|

|

One day I ran

across a passage in a book titled Power Play

that touched directly on my sensitive nerve about courage.

Power Play

Written by Joseph

Finder

Russell:

“Jake, my man, the great tragedy of this century is that

a man can live his entire life without knowing for sure

if he is a coward or not.”

Jake: “Huh.

Never thought about that before.”

Russell:

“You know what’s wrong with the

world today? Computers. They are ruining the

human race.”

Jake:

“Computers?”

Russell:

“You ever see elks mate?

Jake: “Never

had the pleasure.”

Russell:

“Every fall the female elk releases this musk in her

urine. That tells the bull

elks that she is ready to mate.

The bull elks

can smell the musk and they start fighting each other

over the female. They charge at each other, butting

heads, locking antlers, making this unbelievable racket,

this loud bugling. They fight until

one of them gives up and the winner gets the girl.”

Jake: “I’ve

seen bar fights like that.”

Russell:

“That’s how the females can tell which bulls are the

fittest. They mate with the winners. Otherwise the

weak genes get passed on and the elks are gonna die out.

This is how it works in nature.”

Jake: “Or

the corporate world.”

Russell: “No,

that’s where you are wrong. It doesn’t work like that with

humans anymore. Used to be a human who was too slow got

eaten by a Saber tooth tiger. Natural selection, right?”

Jake:

“Didn’t the saber tooth tiger go extinct?”

Russell:

“These days everything is upside down. Women don’t mate

with the better hunter anymore. They marry the rich

guys.”

Jake:

“Maybe the rich guys are

the better hunters now.”

Russell: “Bullshit.

It’s like Darwin’s law got repealed. Call it the

Rule of Weak.”

Jake: “Okay.

Please explain.”

Russell: “Do

you think women can tell which men are the fittest

any more?

Hell no, they can’t!

The women don't

even know where to start.

You see a guy

who is really cut and buff.

He's wearing a muscle shirt to show his body off

and you can figure he spends all his time in the gym.

But you know something? Odds are he’s a faggot. Girl

sees him, thinks she’s in love and hasn’t got a clue

this guy has no desire to reproduce.

I mean, look

at the guys in this picture. This country was made by guys like

Kit Carson fighting savage Indians with knives and six

shooters. Hand to hand combat. Those were brave men.

But that’s all gone now.

The world

today is

run by a bunch of fat-assed wimps who only know how to

Double Click their way to power.

Some

pencil-necked geek sitting at a computer can launch a

thousand missiles with one finger. He kills a million

defenseless

people and

somehow deludes himself into

thinking he's a real tough guy.

Thinks he

should get a Purple Heart for a paper cut.

His idea

of Power is Powerpoint.

These jerks have

headsets on their heads, fingers on

their keyboards

and think they are Macho men when they are really

just half wimp-half machine.

What a crock

of shit.

|

|

They’re

nothing more than sports drink gulping, Instant message

sending, mouse clicking, ipod listening, web surfing pussies.

I am positive that God didn’t mean for the likes

of them to run this planet on the backs of real men.

The problem is, most of the real

men are gone. And

why is that? Because the goddamn

natural selection process has been turned

upside down. The guys who run the country

today think they are fighting men,

but they would beg for their

Mommies if you pulled a knife on them. They go

hunting on the weekend to prove they are men

and kill unsuspecting animals from hundreds of yards

away. That isn't manhood. Any coward could do the same

thing. Those sissies would run screaming

in terror if a

deer had a gun to shoot back with.

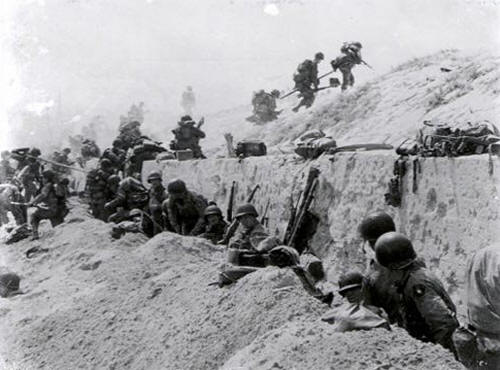

Here's the way I see it. The people

in power today are the sons of the wimps who were

sucking their thumbs and puking their guts out

at the back of

the boats headed to Omaha

Beach on D-Day. After

they staggered off the boat, those cowards

spent the entire goddamn day

hiding behind dead corpses on the

beach. Their

idea of courage was giving themselves a

flesh wound in the leg.

Those

pukes had a bird’s eye view of

the last real men as they went down

in agony fighting for

their country. One by one, those

brave men faced near-certain death as they

ran straight into machine guns on that stinking

Omaha beach. They made the

ultimate sacrifice so the world could get rid of

Hitler and the people they loved back

at home could be safe from that monster.

Meanwhile the sniveling cowards never

lifted a finger to fight the enemy.

Instead they dug

holes in the sand, played dead and

got up when no one was

looking. They went on to

reproduce the

same wimps who run

our country today.

D-Day was the

day that Darwin’s Law died. From then on, it was

Survival of the Weakest.”

|

Strong words, yes?

There is no doubt that many men

my age have never been tested thanks to the brave soldiers

of World War II.

Their sacrifice at D-Day meant that

people like me would probably

never see combat during our lives. Thanks to the countless

men who died in great pain with Nazi bullets ripping their

bodies to shreds,

I have been given

the chance to sit here in the comfort of my home writing

stories at my computer. My mind has trouble accepting

the full extent of the sacrifice.

"These jerks have

headsets on their heads, fingers on

their keyboards

and think they are Macho men when they are really

just half wimp-half machine."

Considering most of my free time is spent

typing away on a keyboard, Mr. Finder's comments cut

straight to the edge of my survivor's guilt.

I hope I am cut out of a stronger cloth than the

double-clicking keyboard pussies of the tirade above, but I

will probably never know. I definitely think Mr.

Finder raises an interesting question:

Would the men of

today have the same courage as the group known as America's

Greatest Generation? Or have we grown too soft?

|

| |

|

The American Cemetery at Normandy is the final resting place for

nearly 10,000 men who died fighting in Europe. The vast

majority of the graves belong to men who died fighting during the

Normandy invasion and during the brutal fighting that took place

throughout France in the month following the invasion.

It is a very humbling experience to see all those graves and

understand these men gave their lives so the rest of us could enjoy

freedom and prosperity.

|

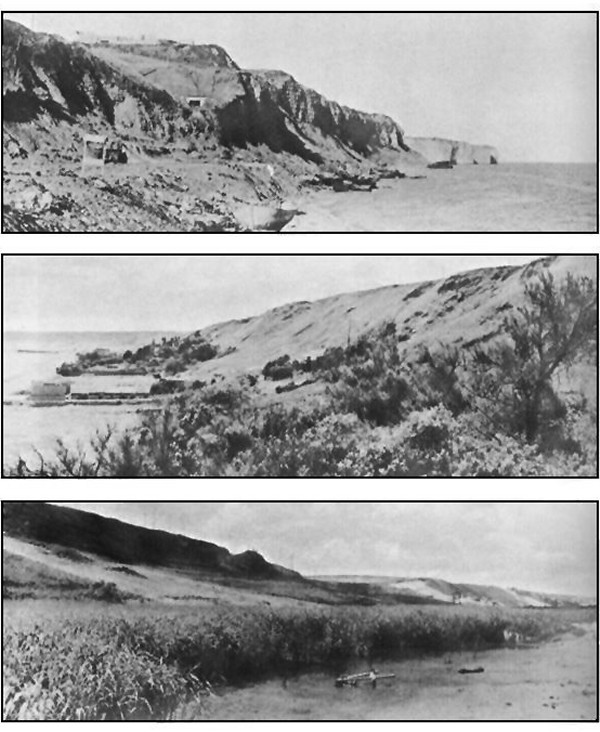

I

photographed the following 30 pictures during my visit. Here

you can see

how the terrain rises. The Platform on the ridge of the hill

is 200 feet above the beach and 700 yards from the

water's edge. The Cemetery and the Platform are side by side.

|

Notice the

woman walking down stairs. There is a walkway directly in

front of that Platform with a staircase on either side.

This curving walkway creates the white Semi-Circle that I

used as a landmark in the Google Earth picture above.

|

As you stand on the Platform

looking out to sea, this is the view to

the left of

the Platform (due west). That is Omaha Beach below.

|

This is the view to the east

of the Platform. You can see the steps that begin one side of the

curving walkway below, i.e. the semi-circle.

|

This is the view

directly in front of the Platform. That little dot on the beach is a

man walking half a mile away.

The mine fields and the

barbed wire were down by the marsh area at the bottom of the hill.

The deadly machine gun nests were located about 100 yards from the

shore. On D-Day there was artillery mounted in the exact spot

where the Platform is now positioned.

As you can see, this

area is beautiful. I don't know if any German or

American ghosts still linger here, but it is definitely a quiet,

peaceful place today.

The Platform had

a very commanding view. The slope on either side of the

Platform is much steeper, creating a bowl of sorts. If you are standing on the

beach, the easiest route to the top of the hill is the view in this

picture.

There is a secret about

the Platform and Cemetery that no one told me about. While

researching this article, I got goose bumps when I realized this

exact spot was the site of the initial breakthrough on Omaha Beach.

When I took this picture, I was standing right where Spalding,

Dawson, and Streczyk made their heroic penetration.

|

|

|

|

|

|

You are looking at two

pictures of the same spot. This is a picture of the exact

trail that Spalding's men took on their way to the top. As you

can see, there isn't much up there to fear. However, this

picture was probably taken AFTER Spalding and Dawson's companies

eliminated the German defense.

|

As I said earlier, I

assumed there were massive fortifications atop the hill. What

I did not realize is that the Germans did not have the manpower to

put guns everywhere. They had to pick their spots. So

why was this area relatively undefended?

|

He [the gunner on the slope above Easy Red] is in a one-man foxhole and

he’s shooting like hell. Finally, we get around behind him. He only

threw up his hands when we got behind him and put a gun to his head.

[Laughs] That’s when he finally found out he was Polish, started talking

Polish.

He says, “I got captured, I don’t want to shoot!” One-man foxhole and

shooting like crazy! Streczyk talked to him in Polish and he got so

crazy with him he punched him. “What the hell are you doing?” Pow!

vinnie digaetano

Phil Streczyk

Everybody reacts different to combat. There are some people that can’t

take it and some people just let it go, you know what I mean? It’s

hard…How somebody’s mind works really. In a million years, you’d never

think that Streczyk would be one of the guys who cracked up, but there

you go, you never know.

He didn’t crack up until the Hürtgen forest. And when you see that…

I think he was one of the most highly decorated soldiers in the

army. He had a lot of awards. He had everything but the Congressional

Medal of Honor.

The war's long effects: Vinny and Chris DiGaetano in conversation

Vinny’s wife Chris joined the conversation and I’ve transcribed their

words as faithfully as possible (and omitted my questions as it slowed

down the text).

Chris: Vinny never really did spoke about the war. Maybe he’d joke. But

he had nightmares, he really did.

Vinny: In the beginning, yeah…

Chris: He had a lot of nightmares. In the middle of the night, all of a

sudden you’d find him sitting bolt upright, angry as all hell, and you

think he’s awake but it’s in his subconscious. We were up in Times

Square, and we were walking up in the theater district, by the

Paramount, and a truck backfired. I was walking along and—where the hell

is he? He had run behind a car, like we were being bombed. He was down

on his hands and knees. I didn’t want to embarrass him. And I said,

“It’s just a truck, Vinny.” You know, it’s sad. Because he’s like the

strong one and to see him crumble was sad.

Vinny: My first job was in printing shop. They cut the paper, it goes

zzzzooooowwhhh. Sounded just like when you’re getting artillery fire. I

start diving underneath the table. So a guy says, “So you were in the

infantry.” He said the first couple times he heard it, he was diving

under the table too. He said it takes about a week and a half to get

used to that sound.

Chris: Vinny’s cousin was with Special Services. They made recordings.

And he came [to a family gathering] with this record of the Screaming

Meemies and he wanted Vinny to hear. It was when we were first married.

We didn’t even have children yet.

Vinny: Oh, yeah…

Chris: And Vinny’s sitting there. All of a sudden he was like, “You

gotta stop it, you gotta stop it soon because I’ll kill him and I’ll

break the machine.” I said, “What? What happened?” He said, “That’s the

noise I heard!”

Vinny: I hate those Screaming Meemies. You could hear them for miles

away. yooeeerrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr…then you don’t hear nothing.

Chris: And then there’s an explosion.

Vinny: It wasn’t like an artillery shell, you could hear them coming in

[all the way]. But we called them Screaming Meemies because we’d hear

them— yaaahhhoowwwweeeeerrr—

Chris: Then silence and then boom.

Vinny: Then it blows up, bowwwrrrrrmmm, because they were like bombs. I

used to hate the noise.

Chris: And this cousin thought it was so, wow, look what I got. He got

such a charge out bringing all those war sounds. “This is wonderful, you

have to hear this.” What the hell is he doing? And then Vinny blew,

“I’ll kill him!” You were really yelling that night. What was wrong with

him? Why would he record something like that?

Vinny: The Screaming Meemie guy, he was married to my first cousin.

Chris: He didn’t want to see Vinny after that. He said, “If that nut is

going to be there, I’m not going.”

Vinny: We never saw him after that. Once or twice maybe. Hardly ever.

Chris: I think your cousin divorced him eventually.

Vinny: Smartest thing she’s done probably.

Chris: That’s a shame, that one [Phil Streczyk] who committed suicide

after the war? I wonder if he ever got help. Because Vinny went for

treatment, for therapy, for eight or ten years, didn’t you, Vinny?

Vinny: Once a week. Kings County Hospital, I used to go. That’s a big

hospital, like Bellevue.

Chris: Psychiatric ward.

Vinny: It was good…

Chris: I think it helped. When he came back from those sessions, he’d be

laughing.

Vinny: The doctor would be like, “Did your father hit you?” “Yeah.” In

those days, if your father hit you it was nothing.

Chris: It wasn’t his father hitting him, it was the Germans. He’d come

back and say, “You should see all those crazy people hanging out the

windows.” I said, “You’d better keep going or you’ll be joining them.”

Maybe [Streczyk] didn’t go for treatment. Sometimes it does help when

you can talk man-to-man, someone who’s professional. They can help you

out. Vinny always used to give way to his outbursts. My mother used to

say, “Don’t get him angry because he’ll get away with it. He’s crazy.

He’s got it on the record that he’s nuts.”

Vinny: Her mother used to say, “Leave him alone, he’s crazy.”

[I asked Chris why she married Vinny despite the problems and her

family’s misgivings. She shrugged and laughed and said, “I thought he

looked like Robert Mitchum.”]

The citation for the British Military Medal states: “For gallantry in

action against the enemy on 6 June 1944 near Colleville-sur-Mer, France.

T/Sgt. Streczyk was one of the first men to enter the maze of trenches

and dugouts, and in desperate hand to hand fighting cleared out

compartment after compartment. In this fighting he captured an officer

and 20 enemy soldiers. He then, with complete disregard for own safety

and without assistance, assaulted and destroyed an enemy machine gun

nest. The heroic and courageous actions of T/Sgt. Streczyk were in

keeping with the highest traditions of the Armed Forces of the United

States.”

|

|

Stan Dzierga

The invasion, well, that was rough. There was a lot of noise….[Stan

shuddered.]

One thing I remember. They told us, when we hit the top of the ridge,

avoid the dry spots in the grass. That’s where the mines are. And that’s

what we did. I guess the grass was starting to dry or they just dug it

up and it didn’t take. And that’s what we tried to do. Avoid them dry

spots when we were walking.

I remember I said to Wally, “Look at those guys running across the

field. Those must be our guys.”

He says, “Hell, no,” he says, “They’re not our guys. That’s got to be

Germans.”

We didn’t have any overcoats on. They had overcoats on and they were

running across the field from the beach we were on. We just made the top

of the ridge and some of them were going back. The Germans were falling

back there.

And the hedgerows were tough. You didn’t know what to expect. And then

you had snipers in the trees. That’s I think how Bisco got killed.

Poor guy, I’ll tell you. What a nice guy. Soft-spoken.

I just…he was right next to me….[Shudders, shakes it off]

|

|

walter bieder

We were ten miles out in the water when we left the ships. And it was

really rough that day. We debarked from the ship by a rope ladder that

came down the side. A couple of guys went down first to hold the ladder

steady when we were coming down. And when you’re coming down, the boat

would be coming way up in the water and then all of a sudden it would

drop down. We finally got everybody aboard, but it was rough.

When we left the mother ship we went out a ways and the landing craft

circled. You have a navy boat there, a navy officer to guide you, to

give you the go to go in. We were all out there circling around waiting

for everybody to get ready, bouncing around there getting soaked, and

guys were puking left and right.

Finally the navy guy said okay and we started and we all spread out and

went in a line until we hit the beach. H-Hour was 6:30. We left the

ships about 3:30 in the morning. So it took about three hours to get in

there.

When we hit the beach, we were the first wave in. The coxswain we had on

our landing craft, he was good. He run the boat up as far as he could

and hit a sandbar or something and said, “That’s as far as I can get

it.” And Spalding said lower the ramp. So we lowered the ramp and jumped

out. First thing, whoop, the water come way up. So we had to wade in and

then crossed a long beach because the tide was out.

The 4th Section of our company, when they lowered the ramp, cross fire

right in there. Four guys got out of that boat alive. They were at the

rear of the landing craft. One of them was a buddy of mine, Cordell. He

told me they jumped over the side, into the water. That’s how they got

out of there.

Our platoon, Spalding’s platoon, we made our way up the hill and kept

pushing. We were sort of spread out. There were a couple of other guys

around me. One guy’s name was Piasecki.

I hit this machine gun nest. It was set not on top of the hill, but just

a ways down and dug in. I had a grenade launcher on my rifle. It was an

armor piercing grenade, but not like a hand grenade. See, the regular

hand grenade we called a pineapple. It was smaller and you had to pull

the pin on it. The grenades that I used, when you fired, it

automatically set off the mechanism in the grenade to explode on

contact.

Our first platoon got up there and I got that one machine gun nest. I

fired at it twice and the second time I hit it.

Farther up, in a little ravine, was a small anti-tank gun and I aimed at

that and I hit that. And then my rifle, I don’t know what the hell

happened with it, the mechanism fell apart, and I had to grab a rifle I

found laying from one of the guys that was hit.

We started taking German prisoners and took a bunch down to the beach.

Then we went right back up and joined the rest of our section. That’s

when Spalding said, “Let’s go.” And so we started pushing back further.

We thought we had elements on our left and our right. But we didn’t. We

were out there alone. And we got caught in a hedgerow.

The hedgerows were square, and thick as hell. They pinned us down in a

hedgerow and they caught us flat-footed. We were there firing back at

them but we couldn’t move because they had us pinned with machine gun

fire. And our forces down on the beachhead didn’t know we were out

there. And the navy was shelling, and we were catching navy shells also.

We didn’t have no communication. From what I remember, our radio man was

knocked or something, I can’t remember. Anyhow, we had no communication

that we was out there. And for the whole day we was pinned down out

there in this hedgerow. They had us really pinned because they had cross

fire and you had to lay flat right up against the hedgerow or you got

nailed.

And that’s where a good friend of mine, Fred Bisco got it so bad. One

helluva guy. He caught it in his face. He had half of his face blown

away. He must have raised up or something and they caught him. He was a

good man.

We were there until it started getting dark and then Spalding and

Streczyk and them decided we’ve got to see if we can find locate the

rest of our company. And we were started pulling out. We kept ten-yard

intervals between men going back and there wasn’t a shot fired at us. I

could never figure that out. They had us there all day long. So we don’t

know what the hell happened to the Germans.

We took off to the rear and finally found the rest of our company.

Captain Wozenski and the rest of our outfit. Wozenski actually cried,

“Where are my men? What did they promise us?”

They were supposed to have bombed the whole beach area and they didn’t

do it. They were no craters at all there.

D-Day night, out of 200 men, there was 60 of us left. Wozenski broke

down hollering, “Where’s my men?” Sixty of us left.

We held up there for five days. They sent the 18th Regiment through us

because we were so battered we couldn’t get going anymore. After they

went through, we moved up farther. And we held up there until they got

replacements up to us. When Wozenski brought all the replacements up, he

was saying, “We’re going to have trouble.” He said, “These guys were

hollering ‘Mama’ when our own artillery was going off.”

So Streczyk and them put each new guy with a guy who’d been through it.

“Take care of them, show ‘em what to do.”

http://warchronicle.com/16th_infantry/soldierstories_wwii/bieder.htm

Unfortunately, we saw a number of bombers get hit by anti-aircraft. I

saw one of them get hit and blow up right in front of us. I’ll never

forget that sight.

And at noon, when they lifted the last wave, we jumped off. It was a

mess out there. St. Lô was just about leveled. I think they had to build

a new St. Lô.

The Germans were always threatening a Blitzkreig. We had our own

Blitzkreig right there.

The German Seventh Army was retreating and our people were divebombing

them and strafing them, tearing them up to hell. At Mons, they were on

one road and we were over here. And eventually we met.

Our platoon got up to a brick wall around a cemetery. The Germans were

running around wild down there and the guys were picking them off. They

were running. A couple of my men, “Fifty bucks I nail that son of a b—.”

We took a lot of prisoners there. Streczyk and somebody else went in a

jeep into German lines and talked a bunch of Germans into surrendering.

And they came in by the hundreds. We teased Streczyk and called him

"Sgt. York" for capturing the whole German army by himself.War of

nerves

One time, I damn near one time lost it but I caught myself. I was

sitting in a foxhole and we were getting shelled. I started just shaking

and finally I just said, “STOP!” and got a hold of myself quick.

I don’t know how I did it but I did. I mean, I thought I was losing it

for a minute. When you get shelled day after day, it kind of gets you. I

can understand why Streczyk and some of those other guys broke down.

People don’t understand that. I’ve heard a lot of guys say [about

someone who broke down], a coward or what? No.

Anybody that ever tells you that he wasn’t scared when he was in combat

is a liar and I’ll tell him right to his face.

Normandy breakout

They were building up for the big push through France. They had the

beach more secure and they had these piers that the engineers built out

there where ships could come in and unload stuff. And then stack it all

up. We had our tanks and so on and so forth.

The day it was to start we were told the Air Force was going to bomb

from ten o’clock to noon. And they were going to bomb steady. You’ve

never seen anything like it. The bombers come at ten o’clock. The sky

was just black with bombers, coming over. Wave after wave, and just

dropping their bombs out in front of us. And all you heard for two hours

was bom-bom-bom-bom-bom....

Unfortunately, we saw a number of bombers get hit by anti-aircraft. I

saw one of them get hit and blow up right in front of us. I’ll never

forget that sight.

And at noon, when they lifted the last wave, we jumped off. It was a

mess out there. St. Lô was just about leveled. I think they had to build

a new St. Lô.

The Germans were always threatening a Blitzkreig. We had our own

Blitzkreig right there.

The German Seventh Army was retreating and our people were divebombing

them and strafing them, tearing them up to hell. At Mons, they were on

one road and we were over here. And eventually we met.

Our platoon got up to a brick wall around a cemetery. The Germans were

running around wild down there and the guys were picking them off. They

were running. A couple of my men, “Fifty bucks I nail that son of a b—.”

We took a lot of prisoners there. Streczyk and somebody else went in a

jeep into German lines and talked a bunch of Germans into surrendering.

And they came in by the hundreds.

Ben Overstreet

Ben Overstreet was a guy who never should have been in the outfit. Not

that he wasn’t a good man, but he was too old. We were fighting, taking

the high ground outside of Aachen, Germany. Whoever commanded that high

ground had the advantage and we used to get counterattacked every

morning by the Germans who would try and knock us off there.

Ben Overstreet got a little excited and he was going to take a hand

grenade and throw it down the hill as they were coming up. Instead, he

pulled the pin and threw the pin and put the hand grenade in his pocket.

All of a sudden he realized it. It was too late and he got away from the

guys.

He was a good man.

Eddie Vaughn

Eddie Vaughn was our mess sergeant. All we had to eat were rations. K

rations, and once in awhile some C rations.

Vaughn says to hell with this. So we were out, this was in France, and

he goes out and nails a nice cow. He went out and slaughtered killed it.

And he brought it into camp and here it was a prize cow from one of

these French farmers. And, boy, they come storming and slamming about it

and Eddie Vaughn says, “Aw, go on, talk to Uncle Sam, they’ll pay you

for it.”

That night we had some steaks, and then we had beef stew, and, boy, we

had really had something good to eat then.

Ray Curley

Ray Curley was a hell of a nice kid who got hit bad on D-Day. And I

didn’t think we see him anymore. Then he got patched up in England and

went AWOL from the hospital. He traced us all the way to where we were

at to come back and join us.

One day we were well into Germany, and I was coming back to my platoon

area. I think it was Fred Reese who came running up to me and said,

“Hey, Sarge, guess who’s back?”

And I said, “Who?”

He says, “Ray Curley.”

And I said, “What?” I said, “What the hell’s he doing back here?” So

when I got back to my platoon area, and I talked to him. I said, “What

the hell are you doing here, Ray? I thought you were home already.”

He went AWOL from the hospital and he hitched his way all the way up to

where we was at. We were well into Germany. I said, “My God, kid, what’s

the matter with you? You should be home by now.”

And he said, “Nah, I wanted to be up with you guys.” So then I had to go

up to talk to our company commander, Captain Caras, and tell him Ray was

back and that he was AWOL from the hospital.

And the old man said, “Well, if he’s AWOL from the hospital he’s going

to have to be sent back.”

I said, “He don’t want to go back.” So I talked the old man into letting

him stay with us and I should never have done that because it wasn’t too

long after that that he got killed.

Fred got wounded and Ray got killed in the same town. (Fred was asking

me if I could remember the name of the town and I’ll be doggone if I can

remember it. He couldn’t remember it either; where he got wounded and

Ray got killed.)

I felt so bad….We were in sort of a hornet’s nest in this town we were

trying to take. The Germans cut loose on us good. Reese caught slugs in

the rear. And Ray got machine gunned, I think it was in his back. He was

running across an open alley when they got him. It was house-to-house

fighting.

That’s the worst fighting: house-to-house, I’ll tell you that.

War of nerves

One time, I damn near one time lost it but I caught myself. I was

sitting in a foxhole and we were getting shelled. I started just shaking

and finally I just said, “STOP!” and got a hold of myself quick.

I don’t know how I did it but I did. I mean, I thought I was losing it

for a minute. When you get shelled day after day, it kind of gets you. I

can understand why Streczyk and some of those other guys broke down.

People don’t understand that. I’ve heard a lot of guys say [about

someone who broke down], a coward or what? No.

Anybody that ever tells you that he wasn’t scared when he was in combat

is a liar and I’ll tell him right to his face.

Thanksgiving in the Hürtgen forest

At Thanksgiving, we were in the Hürtgen forest. It was a cold rainy day.

And they said all the troops were going to have turkey no matter what.

We were sitting in our cold foxholes, water up over our legs and

everything. Cold. But Eddie Vaughan, our mess sergeant, said us guys

were going to get turkey no matter what.

So he made up a whole mess of turkey sandwiches. Then he sent up his

kitchen help with the food on a jeep. They could only come so far we had

to send guys to meet them to carry the coffee and the turkey sandwiches

down to us.

By the time we got that, the turkey sandwiches were cold, coffee was ice

cold, but, boy, it tasted good.

Every once in awhile I stop and I think about that day. Everybody was

soaking wet and you’re sitting in your foxhole, water pouring all around

you.

But those cold turkey sandwiches and coffee tasted good, believe me.

One day there we were pushing up and I was kneeling by a tree and I was

motioning to my men on my right to move up and all of a sudden something

went by my nose and zing hit right into the tree. Here was a sniper, he

just missed me. It just went right across my nose and hit the tree and

knocked out some bark from the tree. I always say the Good Lord guided

that bullet.

The Bulge

The outfit went off the line [during the second week of December 1944]

for a rest. We hadn’t had a rest since D-Day. We were in this town of

Herve, Belgium for a break and that’s when I got a three-day pass to

Paris.

A group of us went back there, even our company commander, Captain Caras.

We were back there for three days. Then we headed back and the Bulge

started.

We come back to our company area, and I wasn’t back even half an hour

when all us noncoms got called to the CP. We were told the Germans broke

through: “Get your men ready. We’re going up to meet ‘em.”

They brought trucks in and loaded us up and we went until we hit them.

The area where the Germans came through was held by the 106th Division

and the 99th. Those guys were fresh from the States, they had no battle

experience. They did an awful lot of damage to the 106th Division, I’ll

tell you that. Just about wiped them out. That’s where we had to go back

up to. To plug the gap.

Christmas in the Ardennes

During the Bulge we pushed up and took this town (we wore white sheets

to blend in with the snow). We had Christmas dinner there in the dining

room of this big house we had taken over there for the CP.

The mess sergeant brought up the meal. We set the table and we took

turns. We had squads out on outpost and then we’d rotate and take turns

so each guy could come in and sit down and have something to eat.

Lieutenant Cowplop

[NOTE: Cowplop was not the actual name of this officer.]

One day, I went to get replacements at the CP, and was walking along

with Captain Caras. I seen this little guy barking orders at these

recruits left and right. I looked at the captain and he looked at me and

laughed, “Ha-ha, that’s your boy, Bieder.”

Lieutenant Cowplop. Stupid and a know-it-all. He didn’t know nothing. He

was shanghaied out of the Army Air Force, and they put him in the

infantry. To this day, if I ever see him, I think I’d walk right up to

him and punch him right smack in the face.

So I got my replacements and took him with me down to where my platoon

was. I had a parameter out, guys guarding on look out and everything and

the rest of the guys were taking it easy. We needed a little break.

Cowplop come into this house I had for the platoon CP and he looked

around and said, “Sergeant! What are all these guys doing here playing

around?”

I said, “They’re just taking it easy. We had a rough battle and they’re

taking it easy.”

He said, “They should be out—”

I said, “I got the parameter all set up out here.”

And he said, “Well, got them up.” They got to be doing this and that.

The guys are just laying there, they looked at me, and I shook my head.

He said, “I gave an order, sergeant.”

And I said, “I know I heard you.”

“You better obey it.”

I said, “No. I’m not. I’m not going to have you coming in here telling

me. You haven’t had no combat experience, you’re not going to come in

here and tell me.”

“I’m going to have you court martialled.”

I said, “You know where the old man is. Go tell him.”

So he didn’t go back but he fussed around and gave me a hard time. And

then we got called up to the CP for a briefing on our next push. So we

went up there and the captain laid out the first platoon will do this,

the second platoon do that.

When we get back to my platoon headquarters, I get all the squad leaders

together and brief them on what we’re going to do. He start giving

different orders.

I said, “Oh, no. You heard what the captain said.”

He said, “Well, we’re going to do it this way.”

I said, “No, we’re not.”

So we shoved off on the attack and I more or less led it. I didn’t pay

any attention to him. Then we stopped and he went back and told the old

man he wants to have me court martialled for disobeying orders on the

field of combat. The old man calls me up there and says, “What’s the

matter, Walt?”

I said, “You briefed us before we made this push. You told us what you

wanted to do. The way the asshole wanted to go, he’d have got us all

killed.”

So the captain looked at him and said, “Let me tell you something,

Cowplop. From now on, till I tell you different, you take orders from

Sgt. Bieder.”

And that set it up between him and me right there.

It was the first time I ever didn’t get along with an officer. When we

went into combat I watched him. I watched him like a hawk. I wouldn’t

turn my back on him.

Before we got to Czechoslovakia, I was asked if I would accept a

battlefield commission and I said yes. Why not, you know?

First, I had an interview with General Taylor. He asked me all kinds of

questions, asked me if I would take it. And I said, Yes, I would take it

if it was offered to me. So he asked me about different battle

situations and that, then he said, “Okay, sergeant, we’ll let you know.”

So I left. Then I didn’t hear anymore about it.

In combat

One time we got pinned down out there in battle. Cowplop was 15 yards

from me, hollering, “Sgt. Bieder! What do you do? What do we do?”

I said, “You’re the goddamn lieutenant, figure it out!” But eventually,

I had to take over.

You really got to size up the whole situation, what you think is out in

front of you there and getting the men to move up in spurts and firing

at the same time.

If you stay there, they’re going to get you for sure. Same way if

they’re dropping mortars down on you if you stay in that one spot you’re

going to get nailed. You got to keep moving no matter if they’re

dropping mortars or not. I had that a number of times with fresh guys

that just come into the outfit. I can remember they were dropping

mortars on us and they were trying to zero in on us and I kept

hollering, “Get up, move!” Because if you stay here they’re going to

zero in on us and they’re going to blast us to hell. I had to run around

and make some of these guys, more or less kick them in the ass and say,

get going! Otherwise, you’re not going to leave here.

The idea is to take the chance of getting up, running, and hitting the

ground firing, and repeat that process until you got up to where you

could get at them or make them run.

We were taking a town one time and we were out in the open and

fortunately I hollered, “Everybody return fire!” We got up and run to a

brick wall outside of this town and I said, “Okay, let’s go.” I told

this one squad leader of mine, “Come on, get your men, get over that

wall.”

He said to me, “There’s Germans on the other side.”

I said, “No s—.”

I went up over the wall and then they followed me. After we secured the

town this squad leader of mine said, “You know, sarge, you wasn’t

supposed to do that.”

I said, “Hell, what were you going to do? Just stand there and let

everything go by, you’re not going to do nothing?”

Just one of the experiences, you know.

The last campaign

The roster would change so fast it was hard to keep up with it

sometimes. My last platoon roster before I left the outfit down there in

Czechoslovakia was altogether different when we first started out.

I have the last roster that I had and it’s altogether different really.

You always had to report the wounded and killed in action, and it would

change all the time. The first sergeant would bring make up new rosters

maybe every couple of weeks or so

When we were in Czechoslovakia we had a lot of new, young boys who

hadn’t been through much at all. They were replacements. When we got the

word to cease firing and all forward movement, the guys starting really

carrying on.

And, boy, I really got mad. I went out there and screamed at them.

"That’s enough! You don’t do this. You think of your fallen buddies!"

When the fighting was over, I got decorated by the Russians. I didn’t

even know it was coming. I didn’t know a thing about it. But one day I

was told I was going to Pilsen to receive a decoration from the

Russians.

Lt. Cowplop heard that I was going to get a decoration and he couldn’t

understand. He told the other sergeants, “What the hell did he do to

deserve that? He don’t deserve it. I deserve it.”

The guys told me all this when I come back from the decoration the next

morning and at chowline for breakfast. He was standing up with the other

officers and I had that medal on my shirt.

I walked up to him and I took the medal, “I understand you deserve this

medal more than me. Here, goddammit.” I stuck it on his shirt, and

walked.

Hutch was standing up there trying to keep from laughing. Cowplop took

the medal and he was so mad he threw it on the ground. Him and I, we

just didn’t get along. I wouldn’t have minded so much if the man knew

what he was doing. I mean, you get some arrogant guys but they know what

they’re doing. This guy didn’t know nothing.

“Where're your bars, Bieder?”

When we were down in Czechoslovakia, the first sergeant called me up to

the CP. He said, “Walt, get yourself a jeep and driver tomorrow morning,

go to division headquarters, and get your bars.”

I said, “What? I don’t want them now.” I said, “I know I got high points

in the company to go home first. I want to get the hell out of here.

I’ve had my fill with fighting and I don’t want anymore.”

I knew I was going home and if I took this commission I had no idea

where I’d wind up. They couldn’t guarantee me that I could stay with my

outfit. And I knew they were taking getting men ready over to the

Pacific for the invasion of Japan. They were looking for experienced

combat men and I just had my fill of combat and I didn’t want to chance

it. And they wouldn’t guarantee me I could stay with the outfit.

Our company commander, Hutch, said, “Take the bars, Walt. What’s the

matter, don’t you want to be one of us?”

I said, “That’s not the point”. I said “It’s not that I don’t want to be

one,” I said, “the thing is can you guarantee me I’ll stay here with the

outfit?”

He says, “You’re sure you don’t want them?”

I said, “No.”

He said, “Okay, tomorrow morning go and talk to the battalion adjutant

and see what he can do about you.”

So next morning I went up to battalion and talked to Captain Fish, he

was the adjutant. He was another one I knew well. He said, “Go on, Walt,

take the bars.”

I said, “Nope, I don’t want them.” I says, “If you can guarantee me I’ll

stay here with my men, fine. But if you can’t, I don’t want them.” I

said, “I know what they’re doing. The Pacific war is still going, and

they’re starting to send guys over there.”

He said, “Sit tight and I’ll see what I can do.” So he called regiment

and I sat there and waited and waited. And regiment called division. And

I still sat there and waited. Finally they came down in the afternoon

and said, “Tell Sergeant Bieder he can go back to his platoon, he

doesn’t have to take the bars.”

When I was coming out of battalion, Wozenski drove up, spotted me, got

out of his jeep, grabbed me and said, “Goddamn it, kid, we made it!”

Then I went back to my platoon and my men were already waiting for me to

give me the business with the bars: “Where the hell are your bars,

Bieder?”

“I didn’t get them.”

Then Hutch, the company commander said, “Re-up Walt, I’ll make you top

kick [first sergeant] and I’ll give you 90 days home.”

That was a good deal I turned down, I should never have turned that

down. But all I had in my mind was getting home. I said, “No, I got top

points and I want to get the hell out of here.”

That evening, the first sergeant of the company then, Russ Harden,

called me up to CP and said, “Walt, get your stuff together, you’re

going home.”

Harden, joined us kind of a late, almost near the end of the war. He

replaced Fitzsimmons who was our first sergeant. He took a second

lieutenant battlefield commission. After he got the commission, I lost

track. I don’t know what happened to him. Russ Harden come in as first

sergeant, he was a hell of a nice fellow, I was pretty friendly with

him. I often wonder what happened to him, I never got the chance to find

out.

So Russ said, “Get your things together, Walt, you’re going home.”

That was June the first. The last day I was there I fell out with my

platoon for retreat and bid goodbye to them all and turned my platoon

over to my platoon guide and said, “I’ll see you.”

Separation

We took off from Czechoslovakia in a DC-3, like they used for the

paratroopers. We flew to Metz, France. We were there a week in Metz for

processing and everything. Then we took a 40/8 French boxcar down to

Marseilles. Spent a week in Marseilles. More processing.

Then we got in a B-17 bomber (they had taken a lot of stuff out of the

inside and put seats in there) and flew us to Casablanca. I had a seat

in the nose of the bomber with the bombardier. That was really nice.

That was a nice flight. We flew up the French coast and over the rock of

Gibraltar. And coming into Casablanca it was really nice. We were

sitting in that nose and you could see that runway coming up at you.

Then we spent 48 hours getting briefed on how to handle yourself in case

the plane had to go down and ditched.

The funniest part of it was the guys I was flying with were all Air

Force. Some of them had been through all this stuff, the ditching and

everything. And there was one other army sergeant there, same rank I

was. Who did they put in charge of this plane to handle things? Us two

army guys.

Then we flew out of Casablanca and then we stopped for fueling in a

little island in the Azores called Santa Maria and they came out with a

bus and loaded us and took us to the mess hall. They treated us top

notch, they treated us like we were VIPs or something. Then we left the

Azores and landed in an air base in Miami. Finished the processing, then

took a train from Miami to Camp Atterbury, Indiana. And that’s where I

got discharged. That was July 1st. It took me one month, all told, from

the time I left the outfit till I got home.

Home again

I worked at a movie theater, learning management work. When the war

ended in Japan in August, people went wild out in the streets and

everything.

I was out there watching them and I just lost it. I started screaming

and crying, ‘Goddamn fools! Get down on your knees and thank God!” The

way they were carrying on, it was terrible. I just couldn’t take it. I

had to go back in the place and sit down, I couldn’t take it.

People should be thankful. Thank the boys who did it and say a prayer

for the boys that didn’t come back.

That’s the way I look at it anyway.

. . . .

I don’t talk too much about this stuff. If I feel somebody understands,

I don’t mind talking about it. But I won’t with somebody who doesn’t

really know what the hell it’s all about.

This is the most I’ve ever gotten into talking this way since the war. I

know Colson said he put a lot out of his mind. I put a lot out of my

mind too.

[The anniversary of D-Day had just passed. I told Walt his old buddy

Fred Reese said he was going to call Bieder on the day and ask if he was

hiding in his basement. Walt laughed.]

I belong to VFW here in Occoquan [Virginia]. Little town right down the

road from us. I went to a meeting that night. I was just sitting there

when they were starting the meeting. I was about the only World War II

man there. One of the guys, the secretary who takes the minutes, he

said, “Before we start this meeting, I want to remind all of you this is

the 57th anniversary of D-Day. And we have one of our own brothers here

that was there on D-Day.” And he said, “Walt Bieder, stand up.”

And they gave me one hell of an ovation. It really made me feel great.

The veterans there where I belong are Vietnam veterans, and there’s a

few Korea veterans. It made me feel good. I wasn’t expecting it.

|

|

D-Day clarence colson dsc

The invasion itself, where we landed, they were supposed to bomb so

there’d be a lot of craters, bomb craters, for us to get into to. But

they missed it, I guess. And [the rocket craft] didn’t get in far

enough. Most of them went in the water. They wasn’t in far enough. I can

remember that part.

Now some of this on that [the Distinguished Service Cross citation]

isn’t true. About cutting wire and stuff isn’t true.

[NOTE: See far right column, top. Another sergeant, and DSC winner, Curt

Colwell cut the wire. The citations may have been mixed up as their

names are similar.]

The assault boat hit a sandbar and dumped us. “Well, let’s get out.” We

had these belts on and you’re in the water clear up to your neck trying

to get in. One of my gunners from the mortar section, said, “I can’t

make it.” And I said, “Dump the gun!” I said, “Come on! Get in alive!

Come on!” So he dumped it. Guys couldn’t make it with the load, you

know, that’s quite a load to carry.

So we got into shore, get everybody spread out as far as we could. You

don’t bunch up you want to get them spread out. 'Course they were

firing, but there was one pillbox way over and there was nothing coming

from that.

There was a minefield in front of us where we landed, but there was an

old house with a stone wall. Sims was one of my main gunners. He was a

good man. We got behind this wall, two of us got there. A lot of them

laying back there was wounded and we pulled some of them up behind the

wall.

This Phelps [indicating the section roster] got wounded on the beach. We

pulled him up behind that wall.

But then there was a path. When I looked and seen that path...there was

this pillbox way over here wasn’t manned. They didn’t have nobody

manning that pillbox. Enemy fire was all coming from this way. So when I

seen that path and all these wires I knew there’s minefields there.

I told Sims. We got a BAR from a guy that was wounded. [I asked if this

might have been Phelps. Colson said, “Yeah, I think, maybe it was.

Because he got wounded, I know.”] And we got a few magazines. I brought

the extra magazines and we got some bandoliers of ammunition that we

carried. And I said, “I’ll head for the hill.” Quite a steep hill. So I

went up the path.

There was no wires across the path, that’s what I was looking for, and

running as fast as I could run. 'Course I was young then, I could move

pretty good. And when I got over there then I motioned him to come. And

Sims came up. And he had some more bandoliers. So we got top of the

hill, and that’s where all the trenches were. And here this one guy was,

running back and forth in that trench and I hollered at him and he threw

a potato masher, a German hand grenade. I ducked down, put my hands up,

my head down. It didn’t go off right quick and I kind of glanced and I

see he hadn’t unscrewed the back and pulled the string. So I nailed him.

But the one that was holding the company up, the pillbox, down there. I

could shoot right down the back end. The pillbox had a door that goes

downstairs, then you have your gunner slots, see. So I got the BAR. It

had a tripod on it and I got it set right up and started spraying that

back door. I told Sims, I says, “Just as soon as I kick that magazine

out, put another one in.” There was 20 rounds, I think, in those

magazines. So we shot about three or four of them. Maybe more, maybe

less. I know it was more than three. We shot quite a few rounds.

All of sudden a white flag came out and we quit firing and they came

out. I motioned for them to come on up and they came up. I don’t know

how more many was dead in there or anything.

That’s why we got all the troops up, pretty soon, on that part of the

beach.

Ramundo got killed. In fact, he was the first guy. When they came up the

same way we did up the hill. He came up right after we got the

prisoners.

He said, “I’ll go back down to get the company.”

And I said, “Don’t go down there, there’s snipers and stuff around

there, too.” I says, “Ramundo, stay here. They’ll come up through.”

But he said, “No, I’m going after them.” He went down, I heard one shot,

I said, “Yeah, he’s had it.” Sniper got him.

The company got up. But out of the whole company we only had, oh, 20 men

or so left. The boat next to me on the right, none of them got out of

it. We was on the further left. As I say, that was a good thing for us

because this pillbox up here wasn’t manned. They didn’t have nobody in

it. Good thing for us.

From then on we just scattered out and moved forward. That was all we

could do.

http://warchronicle.com/16th_infantry/soldierstories_wwii/colson.htm

|

|

|

http://www.ww2lhawebpages.com/THEFIRSTDIVISION/HISTORY_SPALDINGINTERVIEW.html

http://warchronicle.com/16th_infantry/historiantales_wwii/spalding.htm

20Streczyk%20bangalore&f=false

http://www.dday-overlord.com/eng/dday_minutes

http://www.history.army.mil/books/wwii/100-11/ch4.htm

|

|

http://warchronicle.com/16th_infantry/historiantales_wwii/spalding.htm

|

http://www.ww2lhawebpages.com/THEFIRSTDIVISION/HISTORY_SPALDINGINTERVIEW.html

………….

The American victory at Omaha

was achieved against tremendous odds. Omaha Beach will go down in

history as one of the most incredible acts of bravery and

determination in American military history.

Some people, however, call Omaha a

hollow victory when viewed against the heartbreaking loss

of so many young American lives.

Over the years since D-Day, the battle of Omaha has generated a

tremendous amount of criticism. The leaders’ tactics have been

called into question and the military value of sending men into such

clearly prepared defenses has also come under fire.

As remarkable as the victory was, no one can overlook just how close

the Americans came to one of the most depressing defeats in American

history. Was it worth it?

Let’s review the tactics first. It

is fairly

obvious to everyone that whatever could have possibly gone wrong at

Omaha did indeed go wrong.

Eisenhower was warned that the weather was bad and that the seas

were rough. His counterpart Rommel read the same weather reports

and believed no one would be foolish enough to invade in this

weather. Maybe Rommel was right.

-

The weather was so

bad that the assault teams lost the use of all their tanks till

late in the day after the fighting over.

-

The rough weather

created the most havoc with the landing vessels. Some of the

LSTs sunk due to the high waves.

-

Other LSTs ran

straight into the steel spiders based they were impossible to

control.

-

For that matter,

the rough waters forced practically every landing vessel to go

far off track. All day long, no one had a clue where they

were.

-

The biggest

disappointment of the day had to the complete failure of the

aerial bombing and naval shelling to weaken the German

defenses. Again the weather was largely to blame. Unable to

see through the cloud layers, the pilots weren’t about to take a

chance of dropping their bombs on their own men. As a result,

most of the bombs fell far behind the

German defenses.

The truth of the matter is that the American victory that day can be

chalked up to two things – amazing luck and amazing bravery. No one

incident illustrates this more clearly than the moment Sergeant

Streczyk risked his life to blast a hole in the barbed wire with a

hail of bullets.

No man epitomizes the combination of

luck and bravery of the day more than Sergeant Streczyk.

A person has to ask, “What happens if Streczyk

doesn’t blow a hole in the barbed wire? What if he ran out of luck

and got killed instead?”

Good question. The answer is pretty simple – a lot more Americans

would have died at Omaha Beach that day. Yes, the men from the

other four sectors would have eventually surrounded the bunkers and

taken out the defenses above Omaha, but not before hundreds more men

died needlessly on the kill zone beaches.

Streczyk’s cold-blooded heroism at the

barbed wire explains why his company commander later called him "the

greatest unsung hero of World War II".

Streczyk was also lucky. Considering

the number of bullets and mortar that barely missed hitting him, he

was truly a charmed man. His luck closely parallels all the other

lucky breaks the Americans got that day.

Someone will surely ask, “How can

anyone say the Americans were lucky when 2,500 men were

slaughtered?”

Well, for one thing, they were

slaughtered because someone sent them onto that beach without

protection. That’s not bad luck, that is highly questionable

military tactics.

Or someone will ask, “What about all

those tanks that sunk at the start of the battle?”

Again, that wasn’t bad luck, that was

incompetence. Curiously, those tanks operated fairly well at the

other four beaches. 27 of 28 tanks landed at Utah Beach.

Unfortunately at Omaha, the place where they were needed the most,

someone decided to launch the tanks much too far out at sea. The

men who designed them pleaded with the Americans to take them as

close to shore as possible before releasing them, but someone didn’t

listen.

In retrospect, the only real stroke of

bad luck all day was running into the German 352nd at

Omaha. Other than that misfortune, the Americans had luck on their

side all day long.

They were lucky that Rommel had left to

go to a birthday party. They were lucky that the Panzer division

wasn’t released until it was too late. And why not? It seems no

one had the nerve to awaken Herr Hitler from his sleep to get

permission to release the tanks. The Americans were lucky that

their LSTs were blown so badly off course at Utah Beach that most of

the men accidentally came ashore at a place where there were no guns

at all. The Americans were also lucky that the great long-distance

guns of Pointe du Hoc had not yet been installed. Like the movie

The Guns of Navarone, those massive guns would have

ripped the destroyers to shreds when they moved closer to shore.

Yes, the Americans were brave at Omaha

Beach. Incredibly brave.

Unfortunately, after reading all the

stories, it doesn’t seem out of the question that our military

leaders should be held responsible for the heavy casualties.

Someone decided we could just bludgeon the Germans into submission

at Omaha Beach. Consequently a lot of defenseless men died

needlessly. In retrospect, considering Omaha Beach was clearly the

strongest defensive position of the five beaches, a direct paratroop

assault from the rear would have been just as effective

Fortunately the Americans soldiers were

brave enough to overcome the questionable tactics of their

superiors. Leadership can make a difference. Look what Rommel

accomplished. Isn’t it a shame the Americans used Patton as a

decoy? Interestingly, the German 352nd was no match for relief

forces of General George Patton's Third Army during the Battle of

the Bulge.

It almost makes you wonder if the

Germans were right – Patton should have been leading the invasion at

D-Day.

The Big Red monument erected to the 1st Division, stands on top of a

bunker used to house a

searchlight, possibly 50 cm.

Like most of the Atlantic wall this strong point was not completed

by D-day.

WN62 and its sister strong point WN61, just to the east played an

devastating roll on D-day causing many of the American casualties on

this sector of the beach.

Because of the failure to get the swimming tanks ashore (Duplex

Drive) there was no

armour to support the Infantry for several hours. The 75 mm guns

could pick off the landing craft and cause devastation to the troops

trying to get a foothold on the beach.

Around lunchtime a British Frigate sailed along the beach and

managed to put 3 inch

shells into the two casemates. Several did not explode and in the

lower of the casemates you can still see the shells imbedded in the

internal walls of the bunker.

The guns were finally silenced by a Sherman tank supported by

Infantry.

Rommel believed that the invasion needed to be

stopped on the beaches, von Rundstedt, along with Heinz Guderian

disagreed. Hitler vacillated and placed them in the middle, far

enough to be useless to Rommel, not far enough for von Rundstedt. As

a result of this 21st Panzer was placed near Caen, in the area of

the British landings. The SS units that were supposed to support the

division could not be released as they were under Hitler's direct

command.

I was the first one out. The seventh man was the next one to get

across the beach without being hit. All the ones in-between were

hit. Two were killed; three were injured. That’s how lucky you had

to be.

Captain Richard Merrill, 2nd Ranger Battalion.

courage is not the absence of fear, but rather

the ability to act in spite of fear

Captain Edward Wozenski

Commander, Company E, 16th Infantry, 1st Division

In climbing the bluff later in the day, I met Sgt Streczyk coming

down to me on the situation. He stepped directly on a teller mine

righ in front of me nose. I asked what in the hell he was doing

since we both saw the mine clearly.

Streczyk replied, "Well, it didn't go off when i stepped on it going

up the bluff."

If Streczyk did not earn a Medal of Honor, no one ever did.

Thousands of men were on the beach being killed like flies. To even

lift your head over the shingle was to invite quick death. yet

Streczyk led a small group up the bluffs, clearning out enemy

pillboxes, released a flare indciating his breakthourgh, which and

others followed.

by S. L. A. Marshall

First Wave at Omaha Beach

UNLIKE what happens to other great battles, the passing of the years

and the retelling of the story have softened the horror of Omaha

Beach on D Day.

This fluke of history is doubly ironic since no other decisive

battle has ever been so thoroughly reported for the official record.

While the troops were still fighting in Normandy, what had happened

to each unit in the landing had become known through the eyewitness

testimony of all survivors. It was this research by the field

historians which first determined where each company had hit the

beach and by what route it had moved inland. Owing to the fact that

every unit save one had been mislanded, it took this work to show

the troops where they had fought.

How they fought and what they suffered were also determined in

detail during the field research. As published today, the map data

showing where the troops came ashore check exactly with the work

done in the field; but the accompanying narrative describing their

ordeal is a sanitized version of the original field notes.

This happened because the Army historians who wrote the first

official book about Omaha Beach, basing it on the field notes, did a

calculated job of sifting and weighting the material. So saying does

not imply that their judgment was wrong. Normandy was an American

victory; it was their duty to trace the twists and turns of fortune

by which success was won. But to follow that rule slights the story

of Omaha as an epic human tragedy which in the early hours bordered

on total disaster. On this two-division front landing, only six

rifle companies were relatively effective as units. They did better

than others mainly because they had the luck to touch down on a less

deadly section of the beach. Three times that number were shattered

or foundered before they could start to fight. Several contributed

not a man or bullet to the battle for the high ground. But their

ordeal has gone unmarked because its detail was largely ignored by

history in the first place. The worst-fated companies were

overlooked, the more wretched personal experiences were toned down,

and disproportionate attention was paid to the little element of

courageous success in a situation which was largely characterized by

tragic failure.

The official accounts which came later took their cue from this

secondary source instead of searching the original documents. Even

such an otherwise splendid and popular book on the great adventure

as Cornelius Ryan's The Longest Day misses the essence of the Omaha

story.

strongpoint WN64 was cleared around 1000 hours,

although a lone pillbox at the head of the draw remained in German

control until the evening

Perhaps Joe Dawson himself had the best word on the subject. The

former G Company captain wrote to popular historian Stephen Ambrose

fifty years after D-Day: "I feel, Dr. Ambrose, that all honor and

tribute should be given to Lt. Spalding and his small group of men

and to the men of G Company 16th Infantry, for they formed the

spearhead that through luck, courage, and proficiency opened the one

breach in the enemy's defenses that led to the winning of the battle

of Omaha Beach."

Comments on Spalding's Movements

Widerstandsnestern 60

The German forces suffered relative

light casualties from the pre-invasion aerial and naval bombardment.

Though somewhat shell-shocked, they sprang to action quickly, and

even the volunteer units from Eastern Europe fought reasonably well.

As the result, most of the strongpoints were fiercely defended,

forcing the Allies to seize just about every single one by force. As

soon as Gerd von Rundstedt realized that the attack was a major

Allied invasion attempt, he contacted Adolf Hitler for permission to

release all tanks for a counter attack, but permission was slow in

the coming as Berlin still considered the possibility that the

invasion was merely a diversionary attack. Therefore, the only tanks

available were those of Feuchtinger's 21st Panzer Division located

south of Caen. By the time those tanks moved, it was already

mid-morning, and Allied fighters and fighter-bombers had already

established tight patrols in the air, making vehicular movement very

difficult for the Germans.

VON RUNDSTEDT EXPLAINS

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Had I been able to move the armored divisions which I had behind

the coast, I am convinced that the invasion would not have

succeeded."

Lack of air power, and interference from higher levels, played major

roles in the defeat of the German Army after the Normandy invasion,

according to Field Marshal von Rundstedt. But the former German

commander-in-chief in the West has admitted that the Allied

commanders outsmarted him several times to make the situation even

worse.

Caught in the position of a boxer up against an opponent with both a

good left hook and a good right cross, Von Rundstedt guessed

incorrectly that the right cross—the invasion of the Cotentin

Peninsula—was merely a feint to the landing of the left hook—an

invasion of the Belgian or French coast farther north. By the time

he and his successors discovered that the right cross was really the

knockout blow, it was too late to save anything but remnants of the

German Army in France.

A great deal of the interference from higher levels developed later

during the Battle of Germany, Von Rundstedt declared, the worst

instance being the Ardennes counteroffensive of December 1944 and

January 1945.

"The Ardennes offensive bore my name quite wrongly," the former West

Front commander protested. "I had nothing to do with it. It was

ordered from above down to the smallest detail."

He thought, too, that interference from above had wrecked his

earlier plans for the defense of France against the invasion. In the

first place, he did not have enough troops to cover the areas in

which the invasion might come, and higher officers interfered with

the distribution of what he had. When it finally became necessary to

shift troops around, it was too late—by that time Allied planes had

such overwhelming air superiority that they blasted his

reinforcements to bits, or stopped their movement by cutting

communications facilities.

BASIC GERMAN WEAKNESSES

The situation immediately prior to the invasion of June 1944 was not

good, Von Rundstedt said. He and his former Chief of Staff, General

Blumentritt, recognized at least three basic weaknesses: their

inadequate number of troops had to cover enormous stretches of coast

line, some divisions as much as 35 to 40 miles; the Atlantic Wall

was "anything but a wall, just a bit of cheap bluff"; and there was

no counterattack reserve or so-called "Armee centrale," a strategic

army under central command to counterattack where the invasion came.

Von Rundstedt, like many other German generals, said he did not

control Germany's best troops. He complained that many of his best

units were sent to Italy, and he asserted vigorously that it was

"madness to continue the war in Italy that way."

After the collapse of Italy, "that frightful 'boot' of a country

should have been evacuated. Mussolini should have been left where he

was, and we should have held a decent front with a few divisions on

the Alpine frontier. They should not have taken away the best

divisions front me in the West in order to send them to Italy.

That's my private view."

Whether he could have gotten more troops for the West, Von Rundstedt

did not know. He did know that the High Command was hard pressed for

troops on all sides, but nothing was ever done about it.

"It was only decent to do something" after Mussolini was reinstated,

Von Rundstedt admitted, but he added, "of course it was absolutely a

matter of politics and nothing else. I assume, though I have no

positive knowledge, that the High Command was in favor of it."

"I thought that was nonsense, too," Von Rundstedt said of the

occupation of Norway. "What was the point of occupying it?"

He termed the Norwegian operation "purely a naval affair" in which

he had no interest. In fact, his major interest all along was to

accumulate the proper armored divisions, mobile forces which could

be quickly sent where they were needed.

HIGH COMMAND INTERFERED

"Had I been able to move the armored divisions which I had behind

the coast, I am convinced that the invasion would not have

succeeded." Von Rundstedt made this emphatic statement as he told of

continued interference from higher levels with the disposition of

his inadequate forces. "If I had been able to move the troops, then

my air force would also have been in a position to attack hostile

ships."

If he had had his way, Von Rundstedt indicated that the Allies would

first of all have sustained prohibitive losses during landing

operations. In addition, they would not have been able, "with

relative impunity," to bring up battleships close to the coast to

act as floating gun batteries.

"That is all a question of air force, air force, and again air

force," he commented.

The Normandy invasion would have been "like Dieppe on a big

scale"—Von Rundstedt believes—if he had been able to move his

armored divisions as he desired. He summarized the situation with

the statement:

"We would certainly have been better off if a good many things had

been different as regards the distribution of forces."

Von Rundstedt claims that the Atlantic Wall was a "mere bluff," but

admitted that the French coast was more heavily fortified from the

Scheldt to the Seine. Pictured are German fortifications of the more

imposing type.

ATLANTIC WALL MYTH EXPLODED

"The enemy probably knew more about it than we did ourselves," Von

Rundstedt said in referring to the so-called Atlantic Wall as a

"mere bluff." He confessed that such a wall did exist from the

Scheldt to the Seine, "but further than that—one has only to look at

it for one's self in Normandy to see what rubbish it was."

According to Von Rundstedt, the wall consisted of a few pillboxes in

holes in the sand so far apart that "you needed field glasses to see

the next one." The only good thing was the fortresses, such as

Cherbourg and Brest, but they were all fortified only toward the

sea. He described the wall as "a dreary situation" south of the

Gironde toward the Spanish border because "there was really nothing

at all there."

All the ballyhoo about the Atlantic Wall was simply propaganda, Von

Rundstedt said, but he admitted that people believed it—"at least we

believed it." He thinks, however, that it was no mystery to the

Allies because their air photography probably revealed the bluff.

Although a lot of material went into the defenses, Von Rundstedt

complained that the Navy got most of the concrete. He pictured the

German Navy as building higher and thicker roofs on their U-boat

shelters every time the Allies dropped a heavier bomb.

"It doesn't suffice to build a few pillboxes," Von Rundstedt pointed

out. "One needs defense in depth. Moreover, the requisite forces

were lacking—we couldn't have manned them, even if fortifications

had been there."

ARTILLERY WEAKNESSES

The former German commander in the West really warmed up on the

subject of coastal batteries and artillery. Admitting that he was

not an artilleryman, Von Rundstedt nevertheless severely criticized

the mounting of the coastal guns. They were mounted as on ships, and

could fire only out to sea. They were of no use to land forces

because they could not fire in all directions. To make things worse,

the coastal batteries included many captured guns, thus hampering

the supply situation.

As if things were not bad enough, Von Rundstedt complained, the last

divisions he got were very weak in artillery, some of them having

only three light batteries. A good division on land should have nine

light batteries and at least three heavy batteries, in his view.

CAUGHT WITH PANZERS DOWN

Von Rundstedt confessed that the Allies caught him flatfooted with

their thrust out of the Cotentin Peninsula. If he had been in the

position of his enemy, intent on taking Paris and the interior of

France, Von Rundstedt explained, he would have landed to the left

and right of the Seine and taken the shortest route.

The Atlantic Wall, said Von Rundstedt, consisted of a few pillboxes

in the sand (above) so far apart that "you needed field glasses to

see the next one." The only good thing was the fortresses, such as

Cherbourg and Brest (below), he explained, but they were all

fortified only toward the sea.

He admitted that he was puzzled because he believed a landing on the

Cotentin was aimed at securing a harbor. At the same time, he could

see no point in getting a harbor there because the route to the