|

|

MYSTERY OF THE

TEXAS TWOSTEP

CHAPTER SIX:

THE WIZARD OF OZ

Written by Rick

Archer

|

|

Rick Archer's Note:

"Why?" I asked, "is Houston the

only city in America affected by the filming

of Urban Cowboy. What possible

reason can explain why Disco is facing a

premature death here, but nowhere else?"

As I watched Disco die before my eyes, my

conclusion was that some mysterious Wizard

of Oz was responsible for ruining my life.

I probably had more to lose by the Western

Transformation than anyone else in the city.

So a dance club changes its spots. Big

deal. Does the DJ lose his job?

No. The bartender? No. The

waitress? No. What about the

club owner? Nope. From what

people told me, the new Western clubs were

doing a thriving business. Texans like

beer and they like Country music. But

what about me? I was about to lose the

most important thing in the world... my

career as a Disco dance instructor.

That is why I was going mad trying to

understand the reason for these strange

developments that quite frankly did not make

a bit of sense. First and foremost was

the fact that Disco was at its peak of

popularity in every part of the country but

Houston.

Why Houston? And who had the power to

pull this off?

I never got my answer. Or at least I

never got my answer back when it might have

mattered. However, through the miracle

of the Internet, 40 years later I got my

answer. The Wizard of Oz was a man

named Clay Felker.

Due to Mr. Felker's importance to my story,

let's take a closer look.

|

|

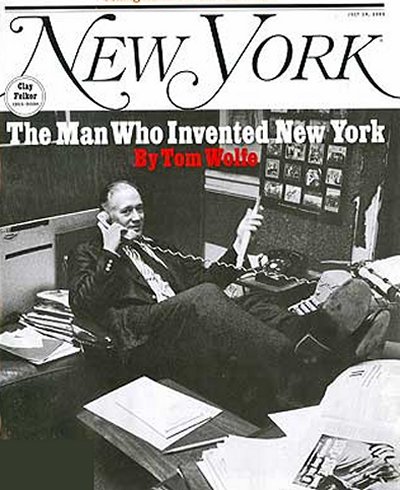

THE MAN WHO

INVENTED NEW YORK |

|

|

If I

can make it there, I'll make it anywhere,

Come on, come through, New York, New York.

-- Frank

Sinatra

|

|

Clay Felker was the embodiment of

Frank Sinatra's

famous song. If Felker could make

it in New York, he could make it anywhere. Coming from

Missouri, Felker was an outsider who wanted to be an

insider. Due to his prodigious talent, he succeeded royally.

Thanks to his

position as editor of the influential New York

Magazine, Clay Felker became the

ultimate New York City insider.

Throughout his

career, Clay Felker was known as a 'trend-spotter'.

In his 2008 obituary, Felker

was quoted about his love for

trend-spotting. Felker said, "Journalism is very often about

seeing

the future."

This was a

fitting observation about a man who time and again

practiced what he preached. Felker tried to

stay ahead of the curve. As a magazine editor,

Felker understood the importance of reporting on

interesting developments well in advance of his

competitors. For that reason he honed a keen eye for

stories that would capture the public's interest

long before they became obvious to rivals of his

magazine.

Sometimes

Felker went one step further. He would see something that

was ready to happen, then authorize a story that fanned the flames

enough to ensure it

actually did happen.

Intimately

connected to the pulse of America as well as NYC, Clay Felker was

one of the most influential journalists of his time.

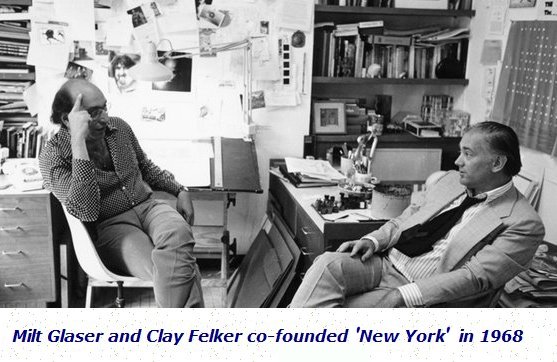

Back in the Sixties and Seventies, Clay Felker was the legendary editor of

New York Magazine. Felker not only

created

New York, he also helped create

The Village Voice. In addition

Felker helped

his friend Gloria Steinem start

Ms magazine.

|

|

|

Due to his plum

position in the media business, Clay Felker was said

to have more contacts than believed humanly

possible. A celebrated

man about town, Felker made it his

job to know

every important person in news, television, politics, theater,

music,

fashion, Wall Street, Hollywood, you name it. As his

writer friend Tom Wolfe put it, "Clay Felker was the

man who invented New York".

As an

example of

New York magazine's influence, Felker's

business partner Milton Glaser

designed the iconic "I Love New York"

logo as a way to boost tourism. In years

since, Glaser's logo has become a widely recognized symbol of

New York City.

Two subjects near and dear to Felker's heart were

'Status' and 'Subcultures'. Felker

called it 'Keeping tabs on the Haves and Have Nots'. Status came first. Felker was fascinated

by ambition and social climbing. More than likely, Felker

developed this preoccupation because he wanted to

be just as famous as the people he associated with.

They say one is defined by the company they keep.

Surrounded daily by important celebrities, Clay Felker became a celebrity in his own right.

Through his magazine, Felker became the quintessential New

York insider, thereby achieving his goal.

|

Felker had a

sense of style. He

wore

custom-made clothes and greeted people with a swashbuckling air of confidence.

With his stunning movie star wife Pamela Tiffin at his side, Felker had no trouble holding his own

with the Beautiful People. Thanks to his position at

the magazine, Felker became just as interesting as they were... which

was the idea all along.

Felker was

intensely curious about the rich. Fascinated

by the

nuances of power and status in the city, he

developed a

unique way to obtain the inside information that his

magazine was famous for. Felker had a fabulous

apartment at 322 East 57th overlooking the East

River. This is where he threw the most

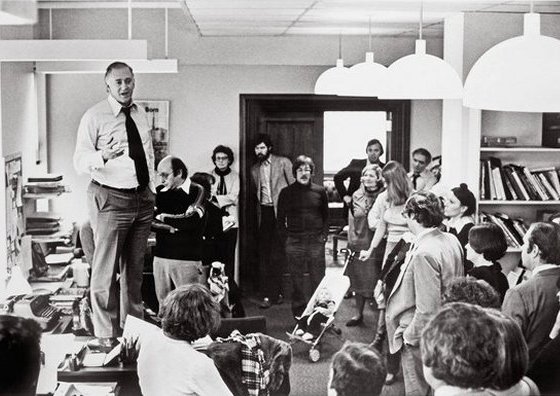

lavish parties in town. Felker's events were the ideal place to rub shoulders with the rich, the elite

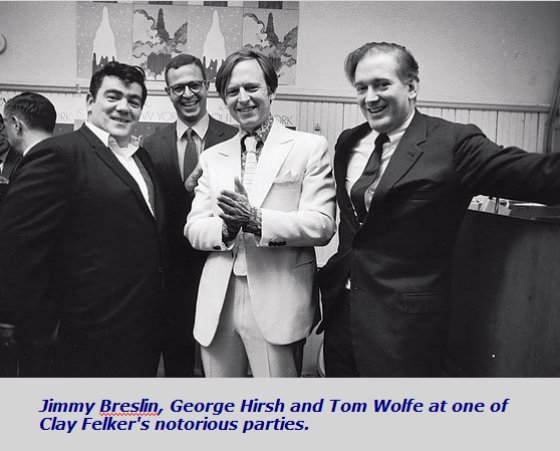

and the talented. Tom

Wolfe joked that Felker's fireplace was such an inviting

place to be noticed that 'at least fourteen status

seekers would stand there all at the same time'.

Felker discovered if he could

get enough important people from different power

corridors in contact with each other, they would

gossip and exchange a treasure trove of trade

secrets. Felker typically held court with

a martini in one hand and a beautiful woman in the other.

If the stories became juicy, no

doubt Felker would snap his fingers to ensure another

martini would appear by magic. Anything to keep them

talking. Felker smiled

as his guests dropped one story after another in his

lap. Felker knew what he was

doing... and so did his guests. And so did his

writers. They participated in Felker's parties for the

same explicit reason.

Clay Felker was

not the only one to benefit. Celebrities enjoyed meeting

their counterparts. Eager to cross-pollinate with

famous guests from different walks of life, an invitation

to a Felker party could lead to deals, insights, love

affairs, and other intriguing possibilities.

This explains why no one dared turn down an invitation to

these much-anticipated events.

|

|

Due to Felker's

ability to shine a city-wide spotlight on an individual,

there was serious competition among the city's elite to be

placed on the cover of the magazine. This is another

reason why the

parties at Felker's apartment were

a popular destination for glamorous people vying for

attention. Others came in hopes of hearing a lucky tip. Everyone knew

a chance conversation with the right person could

lead to a career break.

On Monday morning, Felker would transform

the various disclosures into his next set of

stories. Some tidbits were given intentionally, some

were due to loose lips. Felker would quote anonymous sources of

course, but a cursory scan of his most recent guest list would

typically

suggest the identity.

New York magazine was Felker's baby. He understood that the movers and shakers of New York

were obsessed with Status and were dying to be Noticed as

often as possible. So Felker paid his dues and parlayed his unique position to

gain access to the most interesting people he could find.

In the process, Felker made his magazine a must-read for the movers

and shakers of America's premier city.

|

|

Everyone knew

those smart Upper East Side dinner parties were an extension

of the magazine.

Felker's parties

and his magazine were practically synonymous... each

in turn supported the other.

Through peppery talk on a wide variety of topics such as

politics, real estate, business,

plus scandals about prominent people, Felker was

able to keep a close finger on the pulse of the town. Everyone knew that each issue would contain something sharp, well-informed,

witty and 'trendy'.

As a result, New York

magazine became a target for every aspiring author,

every ambitious politician, shrewd businessman,

hip artist and wealthy socialite hoping to advance their

careers and causes. Wielding the power to decide who

to favor and who to ignore,

Felker became what is

known as a 'kingmaker'.

In addition to

currying favor with the city's cognoscenti, Felker found

time to champion the underdogs as well.

Felker loved to discover hidden nuggets. Felker

understood that 'under the radar' sub-cultures were not going to come to him,

so he was on the lookout for odd stories wherever he went. Clay Felker

always had a stable of creative writers to choose from. As the

ultimate 'trend spotter', Felker made it his business to

notice something interesting, then try to entice one of his gifted writers to poke his or her nose into

it.

|

|

|

New York magazine loved to get its hand's

dirty. As opposed the bland style of the 'offend

no one' New York Times, Felker took special delight in

stories where the Ins and the Outs interfaced awkwardly.

Felker did not bother to conceal his contempt. Using

terms such as 'limousine

liberals', many of the stories he published dripped with barely concealed

mockery. Although his articles outraged both liberals and

conservatives alike, Felker could care less as long as his issues sold out.

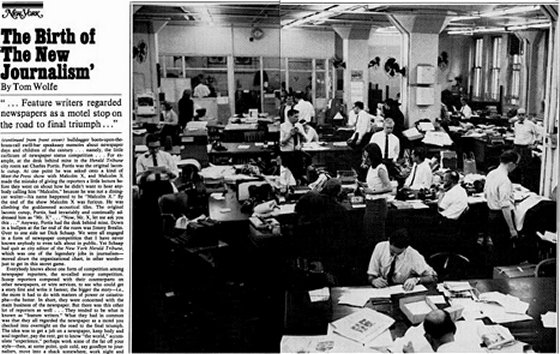

Felker's

in-your-face style came to be known as 'The New Journalism'.

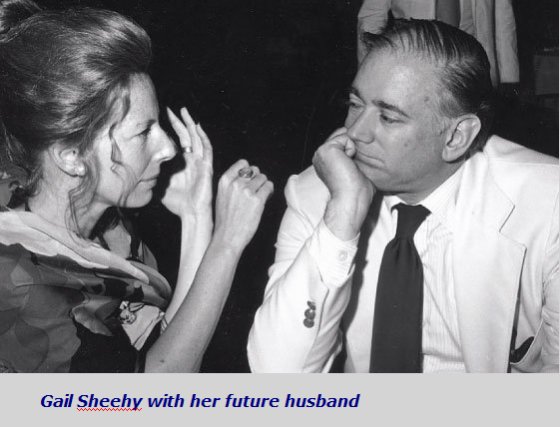

Gail Sheehy, an early feminist, was one of many writers who

got her start courtesy of Clay Felker. Her 1976 book Passages

was named by the Library of Congress as one of the ten most

influential books of the era. Felker became such an

admirer of his star reporter, he married her in 1984.

It is easy to

see why Sheehy achieved stardom. She

enjoyed writing popular Cosmo-style articles

for women on to negotiate a

'Man's World' during the Sixties. Sheehy had a gift for the clever phrase.

As an example, Sheehy described women who

frequented

singles bars during the Sixties in this manner.

"Booted,

pant-suited, birth-controlled and pleasure-goaled."

Gail Sheehy's vivid 1971 report on

prostitution in New York was the result of a Felker suggestion.

He asked to Sheehy to investigate the story from an unusual angle.

He told her to put away

her notepad and nice outfits, then don a disguise. Undaunted, Sheehy took to the streets wearing hot pants, white

vinyl boots and a revealing top. Behind puffed up

hair and too much makeup, the disguise worked to perfection. Gail Sheehy

was able to mingle with the 'working girls' and get

some straight talk. This enabled Sheehy to write an astonishing eyewitness account of the sex

trade.

Gail Sheehy's ability to create scandal was a good example

of Felker's fondness for stepping on people's toes.

For example, her expose of the sex trade caused a firestorm

of controversy. It seems that many of the city's

richest, most powerful families and corporations benefited

directly and indirectly from the illegal sex business.

Understandably, the outrage of the people named was

considerable. In this way Sheehy's sex trade story and

others like it created sensation and

controversy. Someone was always mad at Clay

Felker for something one of his writers had written

about them. This was what the man lived

for. He basked in the glory of knowing his magazine

was on the tip of everyone's tongue because he had

pissed off someone important. Who would be

'Felkerized' next?

Felker

changed the face of magazines.

For example,

Clay Felker added a Lifestyle

section as a way to draw attention to everyday places and

people. His innovation was soon copied by every American newspaper. Be

it counterculture, feminism, obsession with status, Clay

Felker encouraged the citizens to take a close look at

themselves.

It has been said

that Felker's New York

helped the Big Apple discover its

own identity.

According to Ken Auletta, a member of Felker's staff, "New York

was the magazine that helped create the notion of the writer

as the star."

Tom Wolfe was

another of Felker's

first superstars. He turned a Felker suggestion into The Electric

Kool-Aid Acid Test, a fascinating book on the

counter-culture. Wolfe went on to become a best-selling author with books like

Bonfire of the Vanities

and The Right Stuff.

Tom Wolfe never forgot who

his mentor was. In a 1993 interview with the Washington Post, Tom Wolfe

called Clay Felker "the greatest idea man that ever

existed."

|

|

Rick Archer's Note:

"Due to

his plum position in the media business, Clay

Felker was said to have more contacts than

believed humanly possible. A celebrated

man about town, Felker made it his job to know

every important person in news, television,

politics, theater, music, fashion, Wall Street,

Hollywood, you name it."

As one can see, Clay Felker was a very

powerful, very influential man. It is

easy to see how a man with friends in high

places could become

the Wizard of Oz.

"Gail Sheehy's ability to create scandal was a good example

of Felker's fondness for stepping on people's toes.

For example, her expose of the sex trade caused a firestorm

of controversy. It seems that many of the city's

richest, most powerful families and corporations benefited

directly and indirectly from the illegal sex business.

Understandably, the outrage of the people named

was considerable. Someone was always mad

at Clay Felker for something one of his writers

had written about them. This was what the

man lived for. He basked in the glory of

knowing his magazine was on the tip of

everyone's tongue because he had pissed off

someone important."

Felker's in-your-face approach explains how

he developed a

legion of enemies.

We will hear more about

Mr. Felker in a

future chapter. Now back to our story.

|

|

|

|