The War of the Roses

ACT ONE:

The Man Who Would

Be King

|

|

|

The

War of

the Roses was a brutal

Civil War between two powerful families over who

would be the next English King.

After

the

Hundred Years War

(1337-1453) had fizzled out under Henry VI, the

weakling son of the great Henry V, the consensus was

the man had lost his mind. Henry VI was so

incompetent that

the English nobles appointed Richard Plantagenet,

Duke of York, to run the show. The House of

Lancaster had been in charge for the past 50 years.

They were not at all pleased to see a York man in

charge.

The competition to replace Henry VI

became the spark

that ignited The War of the Roses

(1455-1487),

32 year stretch when one man

after another took his best shot at obtaining the

throne. Four different wars were fought and

lots of people died in the process.

On one side was the

House of

Lancaster whose symbol was a red rose. Opposing them was

the House of York whose symbol was a white rose.

Hence the name.

One

unusual twist to the rivalry was the fact that many

of the participants were related to each other.

Since neither side had any better claim

to the throne than the other, they decided to fight

it out. The carnage was incredible.

In the end, only one person

came out smelling like Roses.

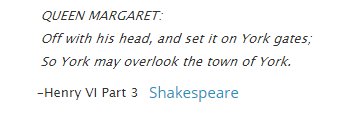

William Shakespeare wrote eight plays. To him,

this period was the gift that kept on giving.

|

|

|

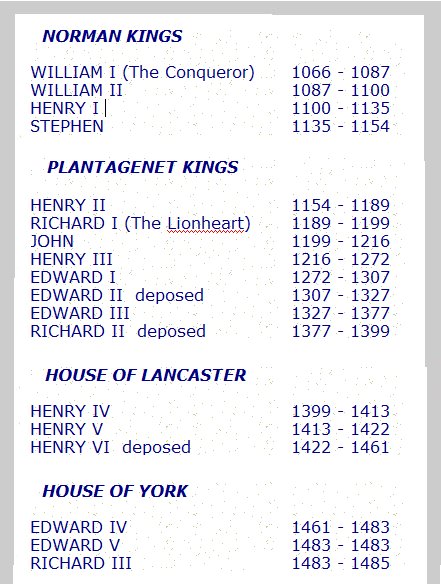

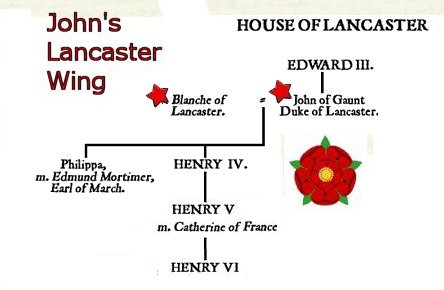

The houses of Lancaster

and York correspond to

the modern counties of Lancashire

and Yorkshire.

The War of

the Roses saw the Yorks and

Lancasters play musical chairs with

the English throne. Starting with

Henry IV, the Lancasters had been in

charge for 50 years. Now the Yorks wanted their day in the sun.

Both

sides gained and lost power multiple

times. In total, the Wars

resulted in five different rulers in the span of

only 25 years, three of whom were killed or executed

by their rivals.

Have you

ever heard of the Lannisters? Have you

ever heard of the Starks? Lannisters =

Lancasters, Starks = Yorks.

The exciting HBO series

Game of Thrones was inspired by the

wildly improbable twists and turns seen

during the War of the Roses.

The War

of the Roses was so brutal it made Game of Thrones

look like kids fighting with wooden swords. It

even had dragons!!

Well,

maybe not. But it should have.

|

|

|

Catherine of

Valois

1415. The jewel in the French crown, Katherine de

Valois, is waiting under lock and key for King Henry

V.

While

the English superman is slaughtering her

kinsmen at Agincourt,

Catherine is praying for

marriage to save her from her misery. But the brutal

king wants her crown, not her innocent love.

For Catherine, England is a lion's den of greed,

avarice and mistrust.

And when she is widowed at

twenty-one, she becomes a prize ripe for the

taking—her young son the future monarch, her hand in

marriage worth a kingdom.

This is a deadly political game, one the dowager

queen must learn fast. She

is an innocent pawn in a

kingdom without a king.

The players—the Duke of Gloucester, Edmund

Beaufort and Owen Tudor—are circling.

Catherine de Valois... Who will have her?

Who will

ruin her? A new dynasty will reign…

|

|

| |

|

|

As we

shall discover, Catherine of Valois, was an unwanted

Queen in her adopted country. Largely ignored,

she would pass through history virtually unnoticed

yet leave a profound, everlasting effect. As

wife to powerful warrior-king Henry V, Catherine

unwittingly played an important role in the upcoming

War of the Roses.

Catherine (1401–1437) was the daughter

of Charles VI of France. Catherine's older

sister Isabella was queen of England from 1396 until

1399, as the child bride of Richard II. Henry

V had been betrothed to Catherine even after the

great English victory at Agincourt. Despite the

French humiliation, plans for the marriage

continued. Catherine was very attractive.

When Henry finally met her at Meulan, he became

enamored. In 1420, after a peace agreement was made

between England and France, Catherine and Henry were

married.

Catherine went to England with her new husband and

was crowned queen in February 1421. Four months

later, Henry returned to France to continue his

military campaigns during the Hundred Year's War.

One would think being married to the daughter of the

French King would calm Henry down, but apparently

not. He was still determined to be the King of

France.

Catherine was several months pregnant when Henry

left. She gave birth to Henry VI. Her

husband never saw their child. During the siege of

Meaux, he became sick with dysentery and died on 31

August 1422. Catherine was not quite 21 and

was left a queen dowager. What would the

future hold in this foreign land?

|

| |

|

Acclaimed author Anne O’Brien

offers her thoughts on

the French woman who found

herself at the heart of

a royal power struggle...

Has there ever been a Queen of England less

acclaimed – so apparently unexceptional –

than Katherine de Valois?

True, she was a Valois princess, daughter of

Charles VI of France and Queen Isabeau; she

became the beautiful young bride of

England’s heroic King Henry V, victor at

Agincourt.

Shakespeare wrote for her a splendid love

scene in Henry V, where Henry declares: “There

is witchcraft on your lips, Kate.”

But Katherine’s early life was not

glamorous, being one of neglect and

starvation, running unwashed and wild

through the Hôtel St-Pol, her father

suffering from bouts of madness, her mother

unapproachable. When packed off to a

convent, Katherine’s education was minimal.

She learned to play the harp.

What she had was royal blood and so she

became a matrimonial prize in the diplomatic

maneuvering to bring peace between England

and France. Henry wanted the French crown

for his descendants, and that is what

Katherine brought as her dowry. Henry would

have wed her had she been the ugliest

princess in Christendom.

This was no

fairytale marriage, and Katherine of course

had no choice in the matter. Nor did life

improve for her as Henry’s

young wife. Out of

the 26 months of their marriage, she spent

only five of them with him in England, and

when left a young widow, she was allowed no

role in the education or upbringing of her

baby son, Henry VI.

Her position was ceremonial, standing beside

the young king when he was crowned or when

he opened parliament.

to be continued...

|

|

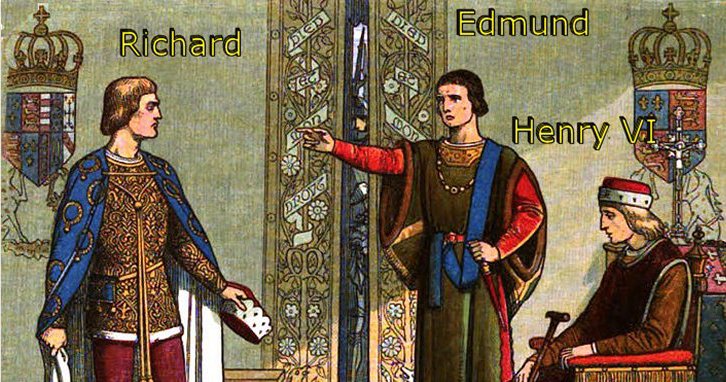

Henry VI

Henry VI, son of Catherine of

Valois. Wow! GOAT might stand for

greatest of all time, but not Henry. He was

the other kind of 'goat'. Poor Henry VI.

He was the King who was treated as a pawn. Nice guy,

but gullible and easily manipulated by his powerful

wife Margaret of Anjou. Unlike

his warrior father Henry V, Henry VI was not suited for warfare.

He was much better at praying.

Gentle, pious and retiring, he came to the throne as

a baby. In the process he inherited a losing

war with France. Under his watch, the Hundred

Years War ended in 1453 with the humiliating loss of

all French lands except for Calais. All that

fighting and nothing to show for it. In August 1453, Henry VI

suffered a catastrophic mental breakdown brought on

by the news of the defeat at the Battle of Castillon

in Gascony, the defeat which finally drove English forces from

France.

Henry VI became completely unresponsive

and unable to

speak. He had to be led from room to room.

This had happened before. Mental illness was

hereditary in his mother's family. During these periods of

insanity, he was incompetent to rule.

Previously when this happened, Margaret of Anjou,

his wife, assumed control of his kingdom. But

this attack was far more severe. The Council tried

to carry on as though the king's disability would be

brief, but eventually was forced to admit something

had to be done.

Henry's ineffectual rule

encouraged the nobles to scheme for ways to

establish control over him. In 1454, Richard,

Duke of York, was made Protector of the Realm.

The House of York challenged Henry VI's right to the

throne and England was plunged into civil war.

The War of the Roses was

about to

begin.

|

| |

Richard of York,

Man of Ambition

|

|

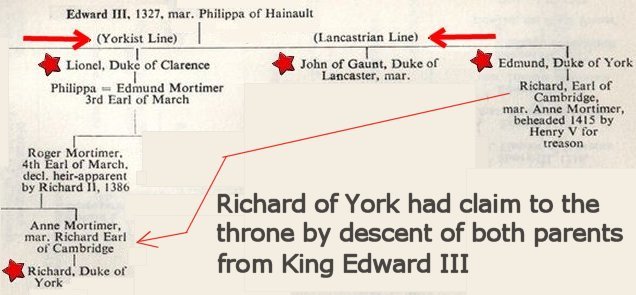

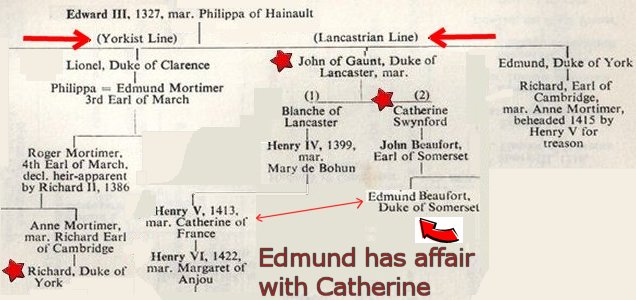

Richard

Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, was a leading English

noble who wanted to be King. Due to his vast

land holdings in Yorkshire, he was the wealthiest noble in England, second only to the king

himself.

Richard

believed his royal lineage was stronger

than any person in England, including the current

King Henry VI. He based his claim on the

lineage of his two parents.

Richard's grandfather Lionel

preceded John of Gaunt in the birth order of

Edward III. Lionel had only one

child, Philippa. In 1368 Philippa

married Edmund Mortimer, 3rd Earl of March.

Their son Roger Mortimer was the man Henry

IV had 'cheated' out of the throne 50

years earlier.

Lionel's granddaughter, Anne

Mortimer, married into the Yorkist branch of

the English royal family and gave birth to

Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York.

Richard of York based his claim to the

English throne on this line of descent from

Lionel, who was the eldest son of King

Edward III to establish a lasting blood

line.

|

|

| |

|

Second, Richard's father was

Richard, Earl of Cambridge. This made Richard

of York the great-grandson of Edward III on his

mother's side and the grandson of Edward III on his

father's side. Descent from not one, but

two of Edward's sons made for a strong claim.

Richard also had a score to

settle. Henry V had beheaded his father

Richard, Earl of Cambridge, for treason in 1415.

Richard had no love for the House of Lancaster or

for Henry VI, son of the man who murdered his

father.

Richard was certain he had just

as much right to the throne as King Henry VI, the

bumbling Lancaster. Legal scholars agreed with

Richard. Unless Henry VI could produce an

heir, Richard was next in line.

1453 was

an important year in English history. In

January, Richard got the bad news: the Queen

was pregnant. If her child was a boy,

Richard's claims would be negated. Then came

more bad news: England had just lost the

Hundred Year's War. Then came the strange

news: The King had gone mad.

Henry

VI, a weak Lancastrian King, had overseen England's

defeat in the Hundred Years' War. This was the

least of England's problems. Due to poor

leadership, the country was beset with social,

political and economic problems. Popular

revolts were commonplace, triggered by the denial of

numerous freedoms. Lacking leadership, the

rich and powerful English nobles took matters into

their own hands. They raised private armies,

engaged in private feuds and openly defied Henry VI.

England was a land divided.

|

| |

With

Henry's mental breakdown in 1453, this was Richard's

big chance.

Richard

was desperate. Noting that Margaret was

pregnant, he needed to take power now. Even if

the newborn child was a boy, it would be 16 years

before the boy came of age. Richard was

willing to settle for that. A lot can happen

in 16 years. Richard told anyone who would

listen that Henry VI had to go sooner rather than

later.

The

barons and nobles agreed. They also agreed

Richard of York was the best qualified man to run

the state. Richard of York was appointed to

govern as Lord Protector during the madness of King

Henry VI. This move, of course, set in motion

dangerous and far-reaching energies.

The

House of Lancaster was not going sit by idly and let

Richard run roughshod over them. Henry VI was

not dead, he was catatonic. In the eyes of the

Lancasters, Henry was 'resting'. In

their opinion, Henry VI should decide who the next

king should be. Furthermore, wasn't Richard

overlooking something? By amazing timing,

Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI, had just become

pregnant. If she were to have a son, the son's

claim would supersede Richard's claim.

Richard

would have none of it. He intended to pursue

the throne, Margaret's pregnancy be damned.

His unquenchable ambition would soon lead England to

the brink of war.

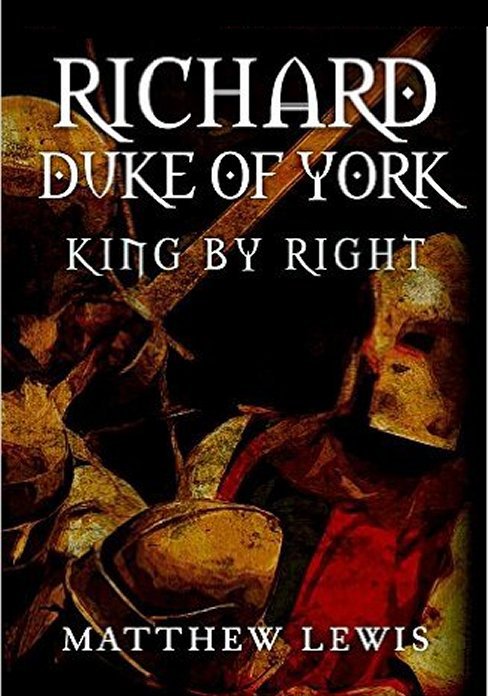

Matthew

Lewis, biographer of Richard, points out that the

enduring reputation of Richard as villain is unsympathetic and

largely unfair. To begin with, Richard had a

legal claim. Richard had every right to pursue

his claim through political means. He had served loyally as Henry VI’s

lieutenant in France on two occasions and then later

in Ireland. Richard performed his roles

solidly, though unspectacularly. The turmoil

of the 1450s

were largely caused by Lancastrian paranoia

and subsequent infighting to stop Richard.

No doubt

Richard, Duke of York, was a complex man capable of

good as well as evil. That said, there can be

no doubt that Richard would go down in history as

the man whose ambition for the crown sparked the

horrible civil war now known as the War of the

Roses. In the eyes of many people, Richard,

Duke of York, would go down in history as one of the

major

villains.

|

|

|

Margaret of Anjou was the Queen of England.

As the wife of incapacitated Henry VI, she

would be equally guilty of

provoking the onset of the War of the Roses.

Margaret was raised in France. She

married English King Henry VI at age 15.

Henry VI was not a successful king.

Henry was more interested in religion and

learning than in military matters.

When he married Margaret, his mental

condition was already unstable.

Margaret cursed Catherine of Valois.

As daughter to the mentally disturbed French

King Charles VI, now doubt Catherine had

passed on this hereditary condition to

Margaret's son Henry VI.

In

1452,

England was falling

apart. Richard, the Duke of

York was persuaded to return from Ireland,

claim his rightful place on the council and

put an end to bad government. His cause was

a popular one and he soon raised an army at

Shrewsbury. The

Lancaster group,

meanwhile, raised their own similar-sized

force in London.

Margaret took charge while Henry simply

wrung his hands.

1453 was much worse. First Henry

learned that England had lost the Hundred

Year's War with France. Then he

learned that Margaret was pregnant which was

fairly miraculous since Henry had not been

intimate. However, he was so out of it

that Margaret was able to persuade Henry

that he had merely forgotten their liaison.

Shortly after his son Edward was born in 1453, Henry

suffered a nervous breakdown.

Now rumors

were rife that the new Prince of

Wales was the result of an adulterous

affair. Perhaps it was this knowledge

that pushed Henry VI over the edge.

After his breakdown, Henry VI was judged

incapable of ruling. So Richard, Duke

of York, was appointed to run the Kingdom.

Richard immediately assumed control.

Not so fast. Margaret of Anjou, Queen

of England, refused to accept any

arrangement that deprived her newborn son - Edward

of Westminster - of his birthright.

Queen Margaret was determined to secure the

throne for her son Edward, but since he was

just a baby, she had no choice but to allow

the Duke of York to take over.

|

| |

|

Queen Margaret would stop at nothing.

Although the Lancasters were nominally aligned

behind King Henry VI, his ill health ensured that he

was never a major player in the coming War of the

Roses. The de facto leader of the Lancaster

faction was instead Henry's cunning wife Margaret.

As the most skilled strategist of the Lancasters,

Queen Margaret was hell bent on putting Richard

in his place.

|

| |

|

Edmund

Beaufort

|

| |

|

Edmund Beaufort, 2nd Duke of Somerset, was

Richard of York's main rival. Edmund was just

as ambitious to become King as Richard. Like

Richard, Edmund noted that Henry VI was still

childless after seven years of marriage. Were

Henry VI to remain without an heir, who would be the

next in line for the crown? Edmund assumed he

had a strong claim. If Henry VI could trace

his right to the throne by pointing to John of Gaunt

and Blanche, well, then Edmund could point to John

of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford.

|

| |

|

Unfortunately Richard of York could make a better

claim. Richard could point to his mother's

lineage from Lionel and his father's lineage from

Edmund. Therefore Richard's claim was stronger

than Edmund's. This explained why Richard was

named Henry's heir presumptive.

Edmund

was disgusted. To hell with Richard of York.

Edmund was going to get the crown by hook or crook.

One of his first moves was the 1427 seduction of

Catherine of Valois, the widowed mother of Henry VI,

age 5.

As the

daughter of French King Charles VI, Catherine was viewed

with considerable suspicion by English

nobles. Afraid she would implant

French sympathies into her son's gullible mind, they prevented

her from playing a full

role in her son's upbringing. Largely

cut off from her son and stuck in the court of a

foreign land that did not like her, Catherine was

pretty much bored, beautiful, and lonely.

Sensing easy pickings, Edmund Beaufort initiated a

torrid affair in 1427.

|

|

This

shook up the English Council. The last thing

they needed was a messy marriage and more heirs.

So they passed a law forbidding Catherine to marry

without the King's approval.

Although

the current king, Henry VI, was quite likely to give

his mother the necessary approval, there was a

catch. Henry was only 7 years old. Until

Henry came of age (16), he could not legally give

approval. Mom would have to stay single.

Very clever.

No

problem. Edmund used his position as

Catherine's one-time sweetheart to become closer to

Henry VI. He did his best to become a a

surrogate father to the boy.

Later,

Edmund would exploit his personal relationship by

persuading the King to promote Edmund to various

royal offices.

|

|

Richard had a

huge wealth advantage.

Although Edmund was the head of one of the

greatest families in England, his

inheritance was worth only 300 pounds.

By contrast his rival Richard had a net

worth of 5,800 pounds. Henry VI made

sure that Edmund was

compensated with offices worth 3,000

pounds. Not only did that bring Edmund

deep within Henry's inner circle, Edmund had

money to raise armies with.

This

patronage served to offend Richard of York

and many of the other nobles deeply. As Edmund's

quarrel with York grew personal, the

dynastic situation got worse, especially in

1451 when Edmund became Henry VI's right

hand man.

Edmund used his inside track in another way.

Edmund was not only Henry's right hand man,

he enjoyed the considerable advantage of

sleeping with the King's wife. When it

was announced in January 1453 that Queen

Margaret was pregnant after seven years of

no results, the matter seemed highly

suspicious.

Henry VI displayed qualities that would have

done credit to a monk, but not to a Medieval

King who was expected to produce an heir.

Henry was pious, naïve, chaste, and prudish.

In addition, Henry VI had a well-known

aversion to physical contact.

Seven years had passed without a pregnancy.

Therefore the pregnancy became seen as

either a miracle or the product of adultery.

Henry VI

himself did nothing to

squelch the rumors. When

asked about the

child's paternity,

Henry declared that Edward must have

been fathered by the Holy Ghost.

Nor did it help that Edmund was made the

child's godfather. The odds clearly

favor Edmund Beaufort as the father of this

child. However, what is more important

is that Henry VI was not the father.

Richard of York knew this and so did

everyone else. Margaret and Edmund

were trying to promote an illegitimate child

to the throne.

|

|

Despite

the objections of Margaret and Edmund, in 1454

Richard of York was named regent as Protector

of the Realm.

Richard

of York, meanwhile, had gained a very important

ally, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, one of the

most influential magnates of the

realm. Warwick was

an English nobleman, administrator, and military

commander. He was possibly richer than

Richard of York himself.

Richard Neville became

known as Warwick the Kingmaker due to his

considerable influence during the infighting to

replace Henry VI.

Warwick

was originally a supporter of King Henry VI.

However, a territorial dispute with Edmund Beaufort,

Duke of Somerset, led him to collaborate with

Richard, Duke of York, in opposing both Beaufort and

the king. The alliance between Richard and

Warwick was aided by the fact that Richard's wife

Cecily Neville was Warwick's aunt.

Once

Richard of York took power, the landscape changed

immediately. Queen

Margaret was excluded

from the Council

completely. Edmund Beaufort's fortunes changed

the moment his rival Richard

of York assumed power as Lord Protector. Richard had

Beaufort imprisoned in the Tower of London and began

looking for reasons to execute him.

Then Richard set about

destroying Beaufort's reputation. Richard's

York supporters spread rumors that the king's

child was illegitimate and that

Beaufort was the father.

Then Richard got to work.

His months as regent were spent tackling the

problem of government overspending.

|

|

Still,

there was the curious issue of Margaret's pregnancy

for Richard to deal with. Margaret gave birth

to a son in October 1453. Margaret immediately

took great pains to quash rumors that Beaufort might

be his father. During her pregnancy, Henry had

suffered a mental breakdown, leaving him in a

withdrawn and unresponsive state that lasted for one

and a half years. This medical condition,

untreatable either by court physicians or by

exorcism, plagued him throughout his life.

Unfortunately for Richard

of York, the birth of baby

Edward removed him from the succession to the

throne. The child was baptized Edward, Prince

of Wales, with Edmund Beaufort listed as godfather.

If the King could return to consciousness, Margaret

intended to persuade Henry to make Edmund Beaufort legal heir to the throne

and protectorate of the Realm till the boy came of

age.

Unfortunately, the King was too far gone to do any

such thing, so Richard's dreams of being king were

still on track.

Then came the

worst surprise of all... Henry woke up.

After a

17-month bout with mental illness, Henry VI remarkably

recovered his reason in January 1455.

As historian Robin Storey

put it: "If Henry's

original insanity was a

tragedy, his recovery was a national disaster."

The

first

thing Henry did was demote

Richard back to the ranks of civilian. Then he

lost little time in reversing

most of Richard of York's actions.

This was a shame because Richard's decisions had

drawn praise for his

even-handedness and willingness to tackle

long-standing problems. Now his initiatives were cut short by

Henry's return. The reforms were

swiftly undone and Richard’s intentions were eyed

with suspicion by the court, members of whom were

the ones who had been disadvantaged by the changes.

Henry

then agreed to recognize baby Edward as his heir,

putting to rest any concerns about a successor.

Richard was out of luck.

Edmund

Beaufort's life was saved by the King's seeming

recovery. Edmund was freed from captivity and

restored to his former position of power.

Having reconvened the court at Westminster by

mid-April 1455, Henry and a select council of nobles

decided to hold a great council at Leicester.

York and his closest allies anticipated that Edmund

Beaufort would bring charges against them at this

assembly.

Seeing

Beaufort released and returned to favor was the last

insult that York would take from his nemesis.

Richard of York was beyond bitter. He was

determined to depose of Beaufort by one means or

another. In May 1455 he raised an army and

tracked down the Beaufort army headed to Leicester.

He confronted Somerset and the King in an engagement

known as the First Battle of St Albans which marked

the beginning of the Wars of the Roses. His son,

Henry, never forgave York and Warwick for his

father's death, and he spent the next nine years

attempting to restore his family's honour.

Facing

with being declared outlaws and traitors, the Yorks

gathered an armed retinue and marched to stop the

royal party from reaching Leicester, intercepting

them at St Albans.

|

|

First Battle of

St. Albans, 1455

On May

22, 1455, Richard, Duke of York engaged the forces

of King Henry VI of England at the First Battle of

St. Albans.

Richard's army outnumbered Henry's army 7,000 to

2,000. Richard attempted to negotiate.

He told Henry to hand over Edmund Beaufort and he

would walk away. Henry stuck by his closest

confidante and refused to give him up.

After

two hours, Richard lost his patience and ordered the

attack. Dividing his forces in two

parts, his first attack failed badly. Warwick

took the second unit through an unguarded part of

the town's defenses, through back lanes and gardens.

|

|

|

|

|

Suddenly

Warwick discovered the market square where the main

body of Henry's troops were talking and resting.

Henry's

men were not yet expecting to be involved in the

fighting. Many were not even wearing their

helmets. Warwick charged instantly with his

force, routing the Lancastrians. Edmund

Beaufort knew that Richard of York would never let

him live. When the Yorkists surrounded his

building, Beaufort was killed in a last wild charge

from the house where he had been sheltering.

Beaufort charged onto the main street and killed

four men before being struck down himself.

His son,

Henry, never forgave York and Warwick for his

father's death. He would spend the next nine

years attempting to restore his family's honor.

The

sudden attack and bravery shown by Warwick began his

famous military career. It would later help

form his nickname as 'The Kingmaker'.

After the battle, Richard of York escorted King

Henry back to London. Richard was appointed as

Protector of England by the parliament a few months

later. Henry VI sat in the Tower of London.

The War of the Roses had begun.

|

|

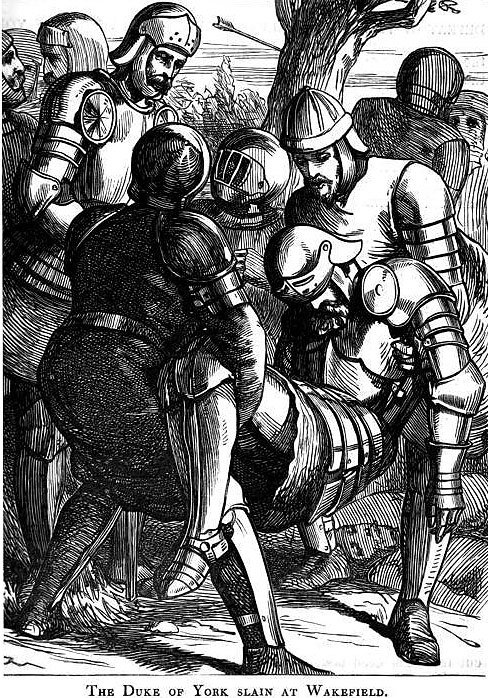

Battle of

Wakefield, 1460

|

|

|

|

|

Over the

next five years, there were rises and falls in the

fortunes of both camps. The Lancasters won the

1459 Battle of Ludford Bridge. Warwick and

Richard both fled across the English Channel for

safety.

In

December 1459 York and Warwick suffered 'attainder', a

legal process that says their lives were forfeit and

their lands reverted to the king. Nor could

their heirs inherit the lost estate.

This was

the most extreme punishment a member of the nobility

could suffer. Now Richard of York was in the

same situation as Henry of Bolingbroke (the future

King Henry IV) in 1398. Only a successful

invasion of England would restore his fortune.

Assuming the invasion was successful, York had three

options: become Protector again; disinherit the king

so that York's son would succeed; or claim the

throne for himself.

It was finally

agreed upon that Richard would not

only rule, he would become king upon

Henry's death. Only one

problem. Within a few weeks of

securing this agreement, Richard

died in the 1460 Battle of Wakefield

(as did Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury and

father of Warwick the Kingmaker).

Richard

of York and his forces convened at Sandal Castle, Richard's

stronghold. A small detachment of Lancastrians

were spotted nearly. Instead of awaiting

reinforcements, Richard led an impulsive charge on

the Lancastrians. It was a trap. Two

large forces of the Lancastrian army emerged from

nearby woods and quickly destroyed Richard's men. Richard, 49,

and his son Edmund,

17, died in the battle.

Why

Richard had exposed himself has never been clear.

One possibility is betrayal by some northern lords who

Richard mistakenly believed to be his allies.

Another explanation was overconfident rashness on York's part.

On the order of warrior queen Margart of Anjou, the heads of

Richard and his son Edmund were placed on pikes by

the victorious Lancastrian armies and displayed at

the Micklegate Bar

in York. Richard's head bore a paper crown. The insult was

clear... after all these years, Richard wore his

cherished crown.

Neither Warwick nor

Richard's eldest son Edward, 19, was at this

battle. When Edward learned that he had lost his father and

younger brother in the

fight, he vowed to avenge the

ambush.

|

|

Battle of Towton,

1461

The

death of Richard of York shook a lot of people up.

In a sense, the Lancasters had killed the future

king. This was not viewed well by the majority

of people. Richard had the same opportunity to

murder Henry VI on two occasions, but had shown the

restraint and respect not to do so.

Instead,

after the Yorkists had

captured Henry in 1460, they had taken the political

route. Indeed, the English parliament

passed an Act of Accord which would

allow Henry to remain as king with the understanding

that Richard would be Regent and would take over

upon Henry's death.

The

Act of Accord was a legally binding

agreement. In a sense, Margaret had broken the

law. Margaret did not care. Margaret of

Anjou would never accept the

decision to remove her son's right to the throne

under any circumstances.

Might makes right. Along with fellow malcontents, she

raised a massive Lancaster army that far out-numbered the York

side.

|

|

| |

After Richard of York was ambushed

and killed at the Battle of Wakefield, nobles who

were previously hesitant to support Richard's claim

to the throne considered the Lancastrians to have

reneged on the Act. Edward found enough

backing to denounce Henry and declare himself King.

The

Battle of Towton was to affirm the victor's

right to bypass the law and rule over England through force of arms.

The battle was

fought in the snow on 29

March 1461, near the village of Towton in Yorkshire.

This was

the grudge match, winner take all.

The York

side was commanded by William Neville, Lord

Fauconberg, a former Lancastrian who had changed

sides to join his nephew Warwick. Fauconberg

faced long odds. He was heavily outnumbered

and part of their

force under the Duke of Norfolk had not yet arrived.

The

initial fighting favored Lancaster, but Lord Fauconberg

saw a way to turn the tables.

Taking note of the powerful wind at their back,

Fauconberg ordered his archers to use the strong

wind to outrange their enemies.

|

|

| |

This

began a

one-sided missile exchange. The Lancaster arrows

fell short of the Yorkist ranks while the York

arrows forced the

Lancastrians into abandon their defensive

positions and retreat to safety.

However,

now that the York side had exhausted their

ammunition, the stronger Lancaster army regrouped

and prepared to charge. Noticing the countless

Lancaster arrows on the ground that had fallen

short, the Yorkist archers plucked the fallen arrows in front of them and continued shooting.

The Lancaster side was hit with a crippling second

barrage.

The

ensuing hand-to-hand combat lasted hours, exhausting

the combatants. The 'better late than never'

arrival of Norfolk's men reinvigorated the Yorkists.

Now they surged forward and routed their foes.

The fighting lasted ten hours. Many

Lancastrians were killed while fleeing; some

trampled each other and others drowned in the

river and snow streams, said to have run red

with blood for several days.

Towton has

been described as the largest and bloodiest

battle ever fought on English soil.

According to chroniclers, more than 50,000

soldiers from the Houses of York and Lancaster

fought for hours amidst a snowstorm on that day,

which was Palm Sunday. A

newsletter circulated a week after the battle

reported that 28,000 died on the battlefield.

|

|

Battle of Hexham,

1464

Following the 1461 Battle of Towton, Henry VI, Margaret,

and her son Edward fled to Scotland to lick

their wounds. It turns out that Towton was not

the end. Margaret of Anjou still had fight in

her. Margaret of Anjou was hated by the

English because she was so ruthless. That

said, did she have any choice?

Margaret's entire existence was wrapped around

restoring Henry VI to the throne and protecting her

son's birthright to be the future king. It was

up to her to fight her husband’s battles and her

son's battles.

After

the 1461 Towton battle, as acting head of the House

of Lancaster, Margaret was able to get the families

to regroup in the north, their base of power.

In 1463, Margaret instigated a rebellion to disrupt

a peace process Edward had initiated with Scotland

further to the north.

Edward

sent John Neville, Warwick's brother, to put down

the rebel force. John Neville was better known

as Montagu since he was the 1st Marquess of Montagu.

Montagu effortlessly put down the poorly organized

uprising.

At the

end of the battle Henry VI was captured again.

Strange as it must seem, this was now the third time

the poor senile man was captured in battle.

Why they kept trotting this poor, senile figurehead out on the

battlefield is a mystery. How weird is it to

keep using a mindless king as a mascot?

|

| |

|

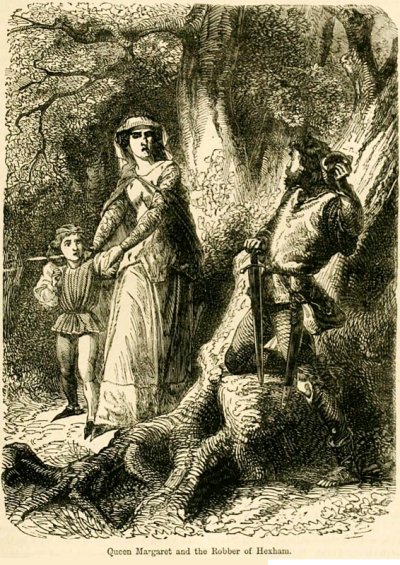

There is

an interesting story attached to the Battle of

Hexham. Margaret insisted on viewing each

battle herself. She was a warrior Queen if

there ever was one. She also insisted Edward

always be at her side for fear as assassination.

Therefore young Edward’s life was spent hurrying

from battlefields to either triumph or exile.

After

the Lancastrians were defeated at the Battle of

Hexham in 1463, Margaret, seized with mortal terror

for the life of her boy, fled with him on foot into

an adjacent forest. Driven by dread, she took

any path she could find just to get as far away from

her enemies as possible. Margaret and Edward,

10, were ambushed by robbers who took Margaret's

jewels and costly outer robes.

While

the outlaws quarreled over who got what, Margaret

snatched her son up in her arms and fled to a

distant thicket to hide. When the robbers

could not find them, they gave up and left.

After waiting hours to be sure the men were gone,

Margaret and Edward came out from hiding.

Wandering lost through the forest, they soon fell

into the hands of another outlaw later that night.

Queen Margaret led her boy up to him and said,

“Here, friend, save the son of your king.”

Surprisingly, the robber took pity on them and hid

them in a cave for two days. The outlaw

spotted one of Margaret’s captains who was searching

for them and told the man where the Queen could be

found them. The captain took Margaret and

Edward to Scotland, whence they finally escaped to

France where they would live with Margaret's

relatives as exiles.

After

the battle, Montagu showed none of King Edward's

conciliatory spirit. Montagu had thirty leading

Lancastrians executed in Hexham on the following day. Maybe this cold-hearted treatment was

necessary. After all, Edward's penchant for showing mercy had not

solved the problem. Like zombies, after every

battle, the Lancasters seemed to get back up and start fighting

again. Not any more. These executions did the trick.

Warrior queen Margaret of Anjou had fled the

country, Henry VI had lost his mind and the

Lancaster leaders had lost their heads.

Lancaster resistance collapsed.

|

|

| |

|

Meanwhile, Edward IV took Henry’s crown and

consolidated his 1461 claim to become England's

first Yorkist king. Edward

did a smart thing. By law, he could have

confiscated the estate of virtually every

Lancastrian noble. Most of

England's leading families had remained loyal to

Henry VI or remained uncommitted in the recent

conflict. Edward did indeed seize the estates of all the

Lancaster nobles who had died during the fighting,

but offered to let the rest keep their lands on

promise of loyalty. This worked like a charm.

Peace came to the land for the time being.

England was done fighting, but only for a while.

In the

aftermath, the new regime relied

heavily on the support of Warwick

and the Neville family who had been so instrumental in bringing Edward to the

throne.

Not long after Edward IV

began his reign, Warwick the Kingmaker decided to

become a

Queenmaker instead.

Now that

the fighting had ended, Warwick began casting about for a

suitable Queen for the bachelor king. This

endeavor would lead to one of the strangest stories

in history.

|

Next Chapter:

War of

the Roses II

Coming soon!

|

|