|

The Man Who Lived

on the Fence

|

A

remarkable drama took place in the days preceding the coming battle. There was great

concern over which side the Stanley brothers would fight

on. Considering Thomas Stanley was on

Richard's English Council, it was assumed Lord

Stanley would fight for Richard. If this was

the case, then Richard had nothing to worry about.

And yet Lord Stanley was married to Henry's mother.

Surely Henry had nothing to worry about. But

then again, Lord Stanley had fought on the side of

Richard during Buckingham's Rebellion. Surely

Richard had nothing to worry about. What was

it going to be?

The

problem was that Lord Stanley and his brother

William had well-deserved reputations for being

sneaky. There had been occasions when both men

showed up at the battle with separate armies, but

only one Stanley army fought while the other army

just stood there and watched.

Lord

Stanley is a fascinating figure because he took many

calculated risks throughout the entire 32-year War

of the Roses, yet emerged completely unscathed.

If someone wished to bypass the romantic mush of the

Red Queen and the White Queen

sagas, they could just as easily tell the entire

story of the War of the Roses through the eyes of

Thomas Lord Stanley.

|

| |

|

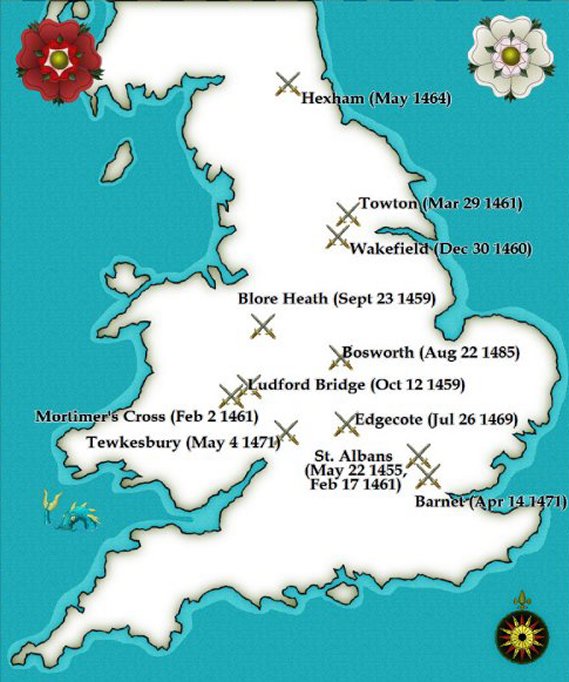

The War

of the Roses can be divided into three parts...

Richard Duke of York, Warwick's

Betrayal, and Richard III.

To

understand Thomas Stanley, one needs to understand

the close relationship of the Neville family to the

York family.

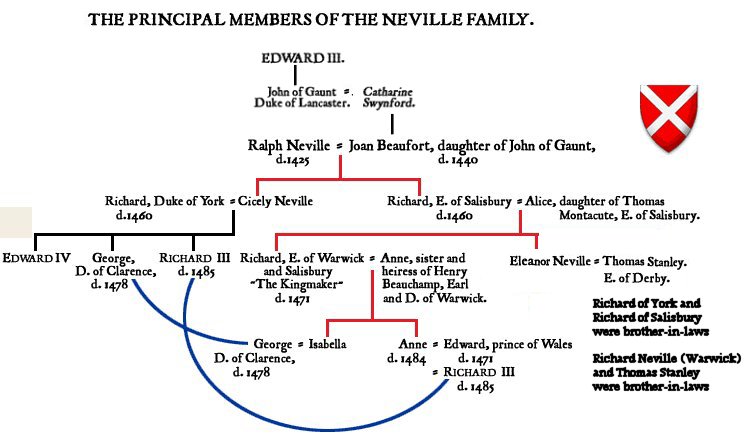

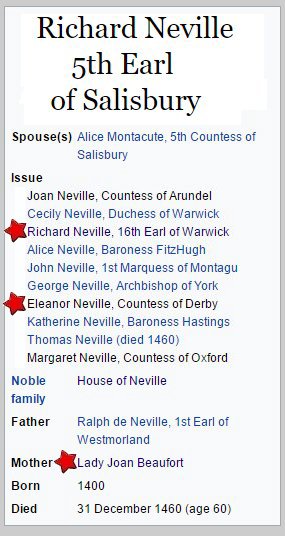

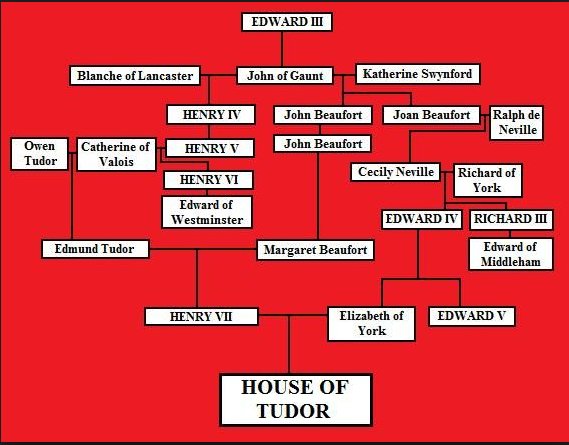

Joan

Beaufort was the daughter of John of Gaunt (who

else?). Joan's son Richard Neville, the Earl

of Salisbury, could trace his lineage straight to

King Edward III. Richard Neville became the

Earl of Salisbury.

Joan

Beaufort's daughter Cicely Neville married Richard,

Duke of York. She too could trace her lineage

to Edward III.

Richard

of York and Richard of Salisbury were not only

brother-in-laws, they were best friends.

Once

Thomas Stanley married Eleanor Neville, he became

part of the Neville family. This marriage made

Stanley brother-in-law to Richard, Earl of

Warwick... the Kingmaker.

|

|

| |

|

15th

Century Medieval England was a period similar to

America's Wild West. Just as the Wild West

cattle barons squared off with complete disregard

for the law, wealthy landowners in England also

squared off with little regard for the law.

Richard Neville, the Earl of Salisbury, was a very

powerful man who had a long-standing grudge with the

neighboring Percy family. 1453 was the year

Henry VI descended into madness.

Simultaneously Henry Percy tried to ambush the

Salisbury family on their way to a wedding.

Although Salisbury's group emerged intact, the

rivalry was reignited.

At this

same time, Richard of York was having his issues

with Edmund Beaufort, the dandy of Margaret of Anjou

and the father of two illegitimate sons related to

our story.

Two

years passed and suddenly the King woke up from

catatonia. Now all hell broke loose.

Richard of Salisbury and Richard of York decided to

team up and confront the Beaufort-Percy combination

at the 1455 Battle of St. Albans, the English

version of OK Corral. The York-Neville team

won handily and killed Edmund Beaufort in the

process, thereby guaranteeing a Round II... and

III... and IV... and....

The Cold

War of the Roses had just gone Hot.

Thomas

Stanley had grown up in a family loyal to Henry VI

and the house of Lancaster. However, in 1457

Thomas formed an alliance with the powerful Neville

family by marrying Eleanor Neville, daughter of

Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury.

This marriage marked the start of Stanley's long

acquaintance with Salisbury's son Richard Neville,

better known as Warwick, the man who would come to

be known as the Kingmaker. As we remember,

Warwick was not only the man who put Edward IV on

the throne, he was also the man who took Edward off

the throne. Hence the nickname.

So here

we have Lord Stanley, a Lancaster, developing a

potential alliance with the leading members of the

House of York. This 1457 marriage to Lady

Eleanor meant Thomas had one foot in the door of the

York-Neville alliance and one foot in service to the

crown. Interesting, yes?? What makes it

even more interesting is that marrying Eleanor put

Stanley in the thick of things, something he had to

know.

Lord

Stanley minded his own business as long as could,

but two years later the War of the Roses paid a

visit to Stanley's back yard. In 1459 Stanley

got news that Queen Margaret of Anjou was recruiting

heavily in Cheshire, his home base. Stanley

knew he could not ignore the civil war much longer.

Making

matters worse, Stanley's father had just died,

making Stanley the new head of the family. As

far as Margaret of Anjou was concerned, the Stanleys

had always been loyal to the crown. So

naturally the Queen came calling to ask for

Stanley's pledge of men. Stanley said he would

send men.

Meanwhile, the Yorkists under Salisbury, father to

Warwick, were mobilizing to neutralize the threat.

Entering Cheshire, naturally they sought assistance

from Stanley, Salisbury's son-in-law, Warwick's

brother-in-law. Stanley said he would send

men.

What a

way to begin one's new role as head of the family!

Caught between a rock and a hard spot, Stanley was

faced with quite a dilemma. Shortly Stanley

got news of a major fight.

Salisbury was commanding the Yorks. He had

just managed to elude the warrior Queen when he was

intercepted by Lord Audley's army at Blore

Heath, a location about 30 miles down the

country road from Lord Stanley's estate in Cheshire.

The battle started as a trap to catch York forces on

the move. Sure enough, the Yorks walked right

into it and suddenly found themselves outnumbered

10,000 to 5,000 (the Yorks were seemingly

outnumbered by the Lancasters in practically every

battle).

Although

Salisbury was outnumbered, through a series of

feints using a small stream that divided the armies,

he provoked the Lancasters into attacking him.

Salisbury's counter-attack proved deadly.

And what

about Lord Stanley? The Royal army under

Margaret of Anjou expected support from Stanley, but

didn’t get it. Although Lord Stanley claimed

to be a loyal royal, he never actually joined Queen

Margaret's army. Furthermore Warwick and

Salisbury expected Stanley would come to their

rescue. Indeed, Stanley showed up, but then he

failed to participate. Warwick was

flabbergasted.

Through

audacious brinkmanship, the young lord faked the

entry of his army into the battle, then suddenly

stopped just a mile away. Lord Stanley sat on

the sideline with 2,000 men and watched.

Meanwhile Sir William Stanley, his younger brother,

did actually fight for the Yorkists at Blore Heath.

William Stanley paid a stiff price as he would later

be attainted for his participation by the Queen.

In the

immediate aftermath of the battle, Lord Stanley had

the nerve to ride up and congratulate Salisbury on

his splendid escape from the trap. However,

just when Stanley came close to committing himself

further, he decided to withdraw his forces back into

Cheshire. Salisbury stood there perplexed.

This was

the start of the Stanley legend. No one could

figure Lord Stanley out. Why did he sit out

that battle? After all, at the time, his

brother-in-law was Warwick the Kingmaker, leader of

the Yorks.

After

the battle Lord Stanley wrote to the Queen to offer

his apologies and offer excuses for why he had not

seen fit to commit his men to battle. Margaret

of Anjou could not have been too convinced by his

explanations. Nevertheless when Parliament

petitioned for his attainder later that year they

were not successful because Margaret intervened.

During the fluctuations of the Wars of the Roses she

needed all the friends she could get, including

unreliable, slippery Lord Stanley.

This was

a close call. The wrong move here could have

meant disaster for the House of Stanley. Lord

Stanley's sympathies were 'York', but Stanley

did not wish to show his true colors till he was

more certain. This set the pattern for Lord

Stanley's career, a man always reticent to commit.

One year

later, the Yorkists had possession of the King and

ruled in his name. Now Lord Stanley decided it was

safe to begin cooperating with the Yorkist lords,

but only when it suited him. Stanley made sure

to stay away from the particularly bloody battles of

Wakefield (where both Salisbury and

the Duke of York, father and son, were killed) and

Towton (where York's eldest son Edward

defeated the Lancastrians and had himself crowned as

Edward IV).

Although

Stanley got no credit for his lack of participation,

he proved valuable to new king Edward by aiding his

brother-in-law, the Earl of Warwick, in mopping up

the remaining Lancastrians. Stanley played a

major part in the capture of Henry VI (1465) in the

Stanley stronghold of Lancashire. For his

service, Stanley acquired several new estates in the

process. For the time being, Stanley was a

York.

In 1469,

a crisis emerged. Warwick changed

sides!! Dramatic shifts between

1469 and 1471 made the political landscape

treacherous. Warwick's decision to switch to

the Lancasters affected Lord Stanley more than

anyone. In 1469, Warwick did his best to

secure Stanley's support against Edward, but Stanley

was non-committal. Consequently Warwick's

first try to eliminate Edward failed. Although

Edward was captured, it didn't do any good.

Then Edward kicked Warwick over to France. Now

Warwick made his alliance with Margaret of Anjou.

Upon Warwick's return to England, Stanley still

refused to fight, but nevertheless lent him armed

support in the restoration of Lancaster King Henry

VI. Edward was unseated and made a fugitive.

Edward ran to Burgundy for safety.

Stanley

was firmly on the Lancaster side now. Or was

he? When Edward began his amazing 1471

comeback, Lord Stanley disappointed Warwick by

refusing to help stop the returning Edward.

Nevertheless, Stanley promised not to help Edward

either. To all outward appearances it seemed

as though Lord Stanley had thrown his lot in with

the Lancastrian cause, but as usual looks were

deceiving. Thomas secretly sent his brother

William to Edward IV’s side when he landed at

Ravenspur to reclaim his throne. As for

himself, Thomas refused to fight.

|

|

| |

Think

about it. If Warwick won at Barnet, Stanley

could point to the men he had given Warwick in 1470

to unseat Edward. If Edward won, Stanley could

point to his 'regret' and 'change of heart'

by deciding to sit out the Battle of Barnet and then

Tewkesbury. Very clever.

Stanley's strategy worked like a charm.

Following Edward's comeback victory at Barnet

and the rout at Tewkesbury, Edward

forgave Lord Stanley for his earlier disloyalty on

the grounds that Stanley had stayed neutral the

second time around.

Lady

Eleanor's death in 1471 was a sad event which

nonetheless led to Margaret Beaufort's invitation to

marry. Stanley recalled how his marriage to

Eleanor had opened the door to his relationship with

the Yorks. Perhaps a similar marriage could

open other doors back to the Lancasters. Lord

Stanley, the undisputed master of moving forward by

sitting still, could not resist. His marriage

to Margaret would allow him to stay firmly in the

middle of any ensuing problems. Lord Stanley

was fairly brilliant in this way.

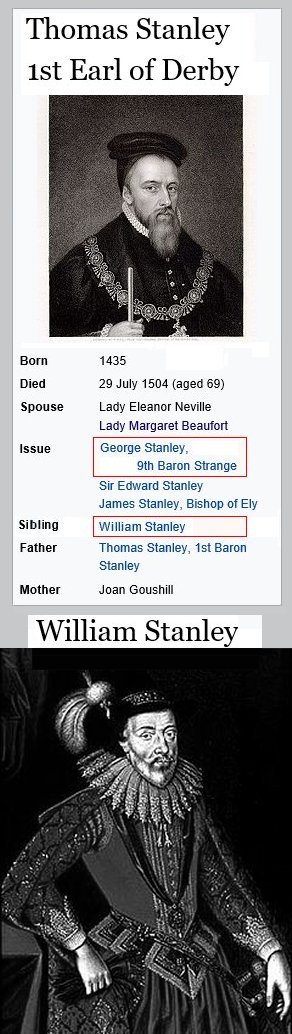

And what

about William Stanley? Stanley's younger

brother William had not only fought during the

Battle of Blore Heath, he would do so again in

several other 1460-1461 encounters. William

repeated this role during the 1469-1471 flare-up.

Seemingly by design, it fell to William to take the

heat off his older brother, the family leader.

William accepted it was his job to fly the family

colors, losing some, winning some, always staying

alive to fight another battle. William might

get attainted, but since Thomas held most of the

family's estates in his name, William's losses

ensured that his big brother never lost anything.

There

was amazing teamwork between the two brothers.

William was willing to take risks knowing in the end

that the House of Stanley always came out ahead.

This sublimation stood in stark contrast to the

destructive squabbling between the three York

brothers. George and Richard constantly argued

over who got which Neville girl and each attainted

estate by playing Edward against the other.

Edward, always the appeaser, did himself no favors

by indulging these two brats. Meanwhile,

William willingly accepted his role as the 'Designated

Loser' for the good of the family. Thomas

always made sure his younger brother was 'compensated'

in one way or another. As much as any family

in England, the Stanleys benefitted during these

turbulent times by playing both sides of the fence.

|

| |

|

Lord Hastings

Revisited

|

|

|

| |

|

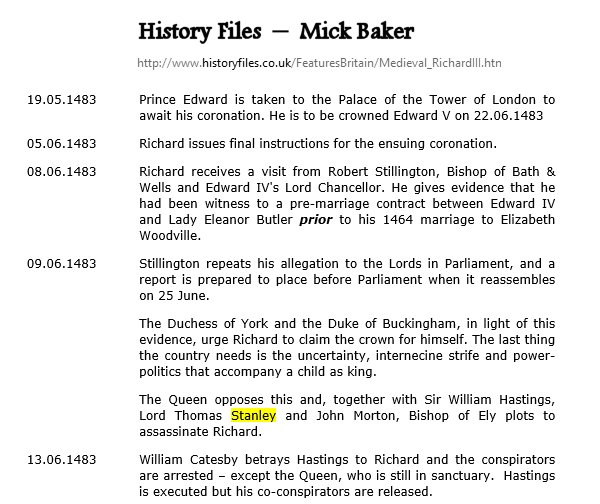

Thomas

Stanley had dodged a bullet in 1483. His close

call took place shortly after Richard had imprisoned

the Princes in the Tower. Their mother

Elizabeth Woodville had fled into sanctuary at

Westminster. Now there were repeated rumors of

plots and conspiracies being orchestrated by

Edward's widow.

Richard

was extremely paranoid that someone would take a

stand against his strong-arm tactics with the two

boys. His fears caused him to erupt on Friday,

June 13, 1483. William Hastings walked into

what he thought was a routine council meeting called

by Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

Hastings

was suddenly seized by armed men. Richard

began screaming at him, accusing the older man of

plotting with the Woodvilles behind Richard's back.

No trial by peers was offered. No proof was

offered. No witnesses were called. The

existence of the plot was upon Richard's say-so

alone.

Richard

condemned Hastings to death. When Hastings

left the chamber a few hours later, it was as a

prisoner being hustled out to execution. His

death on Tower Green was such a hasty affair that no

scaffold had been erected.

Lost in

the drama was a curious fact. Lord Hastings

was not the only council member arrested. In

fact, several of the noblemen in attendance were

arrested. One of them was Lord Stanley who was

roughed up pretty badly in the ensuing scuffle.

Stanley was briefly imprisoned, but later released.

Based on

what we know, who was more likely to be

treacherous... Hastings or Stanley? Lord

Hastings was the man who warned Richard to seize the

boys and take action against Elizabeth Woodville in

the first place. Lord Stanley was a known

snake in the grass. And yet Lord Hastings was

beheaded on the spot while Stanley was set free.

So why did Hastings die and Stanley live?

The

answer is very simple. Lord Stanley made it a

point to use his vast fortune to keep a large,

well-armed army at his disposal back in Cheshire.

Call it an 'insurance policy'. Richard

knew Stanley's son George, Lord Strange, could

quickly mobilize this army in northwest England.

In addition, brother William had his own army as

well. Supreme in the Midlands countryside

around Shrewsbury south of Lancaster, the Stanleys

had become the most powerful family in England.

And Richard knew it.

|

|

There is

little doubt Richard III feared Lord Stanley more

than anyone. Sensing Richard's fear, in the

days to follow, Stanley played Richard like a

fiddle. Keeping his cards close to his vest,

Stanley kept Richard guessing.

On the

one hand, Lord Stanley's weird move to marry

Margaret Beaufort, the Lancaster matron, just added

to the confusion. On the other hand, despite

his odd choice of marital

partner, Stanley had never done a single thing to make

King Edward IV suspect Stanley's loyalty to the Yorks in any way

during the twelve years of peace.

After Edward's

death in 1483, Lord Stanley had been the first man

to congratulate Richard. Then came the master

stroke... after Richard had threatened Stanley's

life with false (??) accusations, Stanley forgave

Richard. "No harm done, lad."

Two

weeks later, guess who carried the great mace at

Richard's coronation?

Then,

just to further prove his loyalty to Richard,

Stanley actually fought at the side of

King Richard during Buckingham's ill-fated

Rebellion. Joining

Lord Stanley in the battle was his younger brother

William Stanley.

"See,

Richard, you have nothing to worry about. The

House of Stanley is firmly in your corner!"

Richard's fears were allayed, at least somewhat.

Now Richard tried to buy the Stanleys off. After the

rebellion was over,

Thomas and William Stanley were richly rewarded from

the forfeited estates of the dead rebels. Thomas

Stanley had performed so well he was appointed to

Buckingham’s position as Lord High Constable of

England. Sir William was made Chief Justice of

North Wales and was given land as well.

|

|

| |

|

As

always, Lord Stanley had made the right move.

He had converted Richard's paranoia into vast new

estates and position.

There

has long been speculation why Stanley sided with

Richard in the Rebellion and not his own wife.

Here is one possible reason:

"Richard was with the Earl of Northumberland and

Thomas, Lord Stanley, when he got word of the

rebellion. Richard did not really trust

either man as in the past they seemed to support

Lancastrian causes in the past.

Northumberland (Henry Percy) had proved to be

difficult during the years when Richard was Lord

of the North. The Late King Edward had to send

Northumberland orders, as he would not obey

Richard.

The same could have been said about Stanley.

He spent most of the time in whichever camp

benefited him the most. Richard kept

him under close eye as trouble and Stanley was

always close at hand. Richard was

reminded of Stanley’s wife, as he had heard that

Henry Tudor was playing a major role in the

Buckingham rebellion. (Source)

In

the weeks to follow something deeply unsettling came

to light. After

the dust had cleared, Richard III made a remarkable

discovery... Thomas Stanley's wife Margaret Beaufort

had been largely responsible for organizing and

funding the operation. Now Richard was very

confused. Thomas Stanley had fought hard for

him and yet Stanley's wife Margaret Beaufort was a

key conspirator in the rebellion. Whose side

was Stanley on?

Lord

Stanley was asked to explain. Stanley replied

to Richard that his wife's affairs were unknown to

him. If Stanley had known, he would have told

her to knock it off. Besides, did Richard not

see how hard Stanley had worked to put down the

rebellion? What further proof of his

innocence... and ignorance of his wife's moves...

did Richard need?

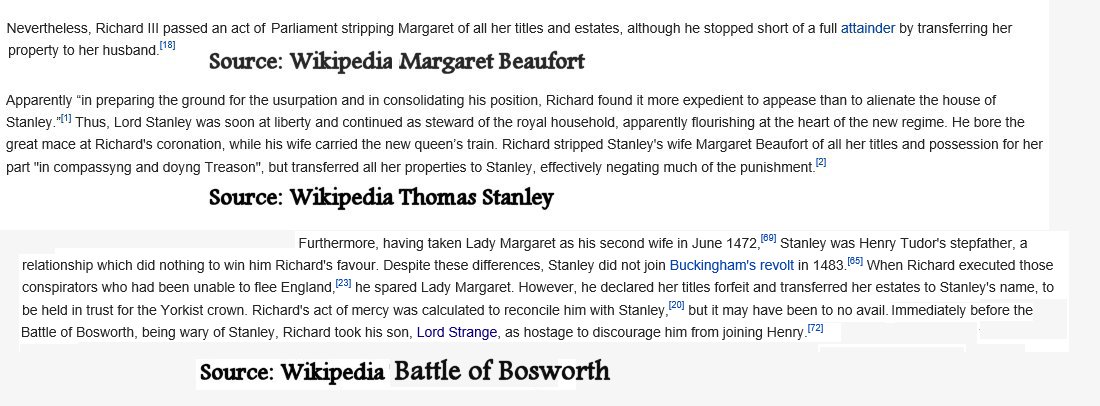

Richard

was really confused. What should

he do about Margaret? Under

normal circumstances, Margaret would have been

executed or imprisoned. But Richard did

neither. With visions of that standing army in

Cheshire, Richard decided to take Stanley's word. Such was the strength of Thomas

Stanley that Richard let Margaret off with a wrist

slap rather than antagonize her powerful husband.

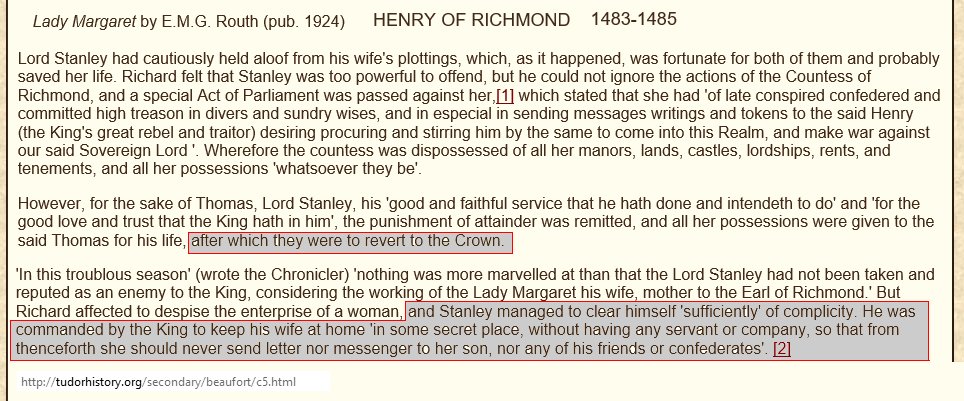

Lest we

forget, Richard did something unusual... Richard handed

all of Margaret's estate to Thomas. Lord

Stanley now owned his wife's entire estate.

However, there was a catch. Upon Stanley's

death, Margaret's estate would revert

to the crown.

| |

|

|

| |

|

Rick Archer's Note:

Doesn't this story strike the Reader as a bit

odd?

Here

is a woman, Margaret, who has just committed

treason and Richard has undeniable proof of her

complicity. Previously, Richard put Lord

Hastings to death for less evidence than he had

here. In addition, Richard has just

finished beheading Buckingham. But Richard

treats Margaret differently for the same crime.

Richard never even speaks to Margaret, the real

instigator. Instead he speaks to Thomas

Stanley and tells him all his wife has to do is

promise not to do it again, then go home and sit

in the corner. While she's at it, maybe

pray a little and repent.

The

thing to understand in my long saga is that I

originally set out to write a brief overview of

English history. Hence the title "Brevity

and Brexity". As it turned out, I

spent a month and a half researching and writing

this story. So much for Brevity.

I

invested my time because I began to see more

clearly how History is written. Things

happen, but since very few accounts exist,

everything becomes wide open to interpretation.

In particular, the 'Winner' gets their

version accepted as the undisputed 'Truth'

of what took place. The Winner picks

someone to write a favorable story or the Winner

makes sure that unfavorable documents

disappear... or both.

The

secret of interpreting History is to put oneself

in the place of the actor and imagine what must

have passed through their minds. On a

personal note, as one has surely guessed, Lord

Stanley definitely caught my eye.

The

story of 'Margaret's punishment'

seemed so absurd that I gave it a lot of

thought. My

problem is that write each story based on web sites

that usually just scratch the surface.

Based on what I read, I initially thought this estate-transfer/house

arrest solution was Richard's

idea. But then I began to wonder.

That is when it crossed my mind that maybe this

solution was Stanley's idea.

So here is my interpretation of how the scenario

might read if Stanley took control of the situation.

Richard:

"Lord Stanley, you were

invaluable to me in

putting down the rebellion. How do you suggest

I handle this matter of your treasonous wife??"

"Sire, I ask you to spare her. She is but

a silly woman who let her fever for her son

cloud her judgment. I suggest you place

her under my control. Strip Margaret of

her estate and give it to me. Without

money, she can do little damage.

I

will oversee the lands myself. And when I

die, let Margaret's estate revert to the crown.

I will order Margaret to stay close by, a form

of house arrest. She is not to leave my

home without supervision. You will have

nothing more to worry about, this I pledge."

In other

words, stripping Margaret of her estate may not have

been Richard's idea, but rather her husband's idea.

By betraying Margaret... for whatever reason...

during the Rebellion, suddenly Stanley had acquired

Margaret's vast estate for himself. And what

if something were to happen to Richard??

Gee, too bad, then after Richard was gone, Stanley

could petition the next king to either let him keep

it all or give it back to Margaret. Either

way, Stanley had made a shrewd bargain. Better

to keep the lands and titles in the family than give

it to Richard.

But how

would Margaret react? After all, Lord Stanley,

master manipulator, had gotten his wife declared a traitor and

placed in his care under house arrest, with all of

her lands and fortune forfeit unto him.

Margaret had to be incredulous.

Wouldn't

it be fascinating to be a fly on the wall when

Margaret learned the news? Let's fantasize how

the dialogue might go.

“On

the graves of my ancestors, I swear, Stanley,

you have robbed me! Did you betray me just to get my fortune?”

"Calm down, Margaret. I have not

betrayed you. I was stuck at the side

of the King when the fighting broke out.

He never let me out of his sight.

Thanks to all that flooding, I could already

see that Buckingham's uprising did not have

a ghost of a chance to succeed. There

were reports that his own men had deserted

him. I was not about to throw

everything we have worked for away on this

failed scheme. There's an old saying,

'Better to live and fight another day'.

So, yes, I fought for Richard and so did my

brother. What choice did I have?

Buckingham was a lost cause.

Now, as for the deal I struck, when the

discussion began, Richard was so angry he

was about to sever your head from your

shoulders. Then he discussed a certain

cold dungeon with unusually meager rations

and thin blankets. In addition, you

were about to be attainted. Richard

was completely within his right to remove

your entire estate. Who would you

rather have in control of your estate,

Richard or me?

But I talked him out of it. I not only

saved your life, I saved your estate.

Your holdings are quite safe with me.

All we have to do is remove Richard and your

son will be able to restore your lands to

you."

Please keep in mind that I have just made up

History. I have no idea whether this

conversation took place or what was said. But

if we look at history from Stanley's point of view,

my scenario makes sense.

If this

conversation did take place, was Stanley telling the

truth? Who can say with this guy? But

his argument was compelling enough for Margaret to

buy his story. Plus, what other choice did she

have? Stanley now owned all of Margaret's

lands.

If there

was to be a coming battle and Henry won, Margaret's

lands would be safe AND Stanley would be rewarded.

So Margaret's fears were allayed when she realized

it was completely in Stanley's interest to help

Henry win.

However,

if Richard won the coming battle, Stanley was in big

trouble... unless Stanley could find a way not

to oppose Richard. Stanley had to find

a way to help Henry and stay neutral at the same

time. Now how does someone do that? I

guess we will find out when the time comes.

It was

now 1485. Two

years had passed since Buckingham's Rebellion.

Henry Tudor was coming for Richard.

The support of Thomas and William Stanley were critical

to the king. Would Richard be able to count

on these men again like he had during the rebellion

of 1483? Richard was desperate to find out.

Richard was about to

discover exactly what he feared the most... Lord

Stanley was sitting on the fence.

|

Defections

|

| |

|

What a

shame Richard's immense talent had to go to waste.

If one can disregard Richard's ruthlessness, then he

should be admired for his courage and intelligence.

As a mere teenager, he helped his brother Edward

regain his crown. Richard's attack at the

Battle of Barnet won the day against far older and

more experienced opponents. Weeks later,

Richard's defense at Tewkesbury won the day by

thwarting the Duke of Somerset's surprise attack.

Ever

since Henry Tudor's escape during Buckingham's

Rebellion, Richard had known this showdown would come.

Well aware that Henry Tudor would be sailing soon,

Richard had been clever. Since Richard was

uncertain where Henry would land, he posted

his men in the epicenter of England. His men

were 100 miles from all the likely landing spots, a

three-day horse ride.

Richard's strategy was to let the local commander

keep Henry occupied long enough for Richard's

reinforcements to race to the spot. A landing

party would not have enough time to unload their

ships and gain a foothold on English soil.

Richard's counter-attack would destroy the

vulnerable invasion force.

|

|

| |

|

Interestingly, German General Erwin Rommel expected

to use this same strategy when preparing his D-Day

defenses. Unsure where the Allies would land,

Rommel kept a crack Panzer tank unit on the

Belgium-French border so it could race to whatever

point the Allies landed and decimate the attack

while the men were still pinned down on the beach.

Rommel's

strategy may very well have worked except for one

thing.... Rommel needed Hitler's permission to

release the tanks. Unfortunately, Hitler had put a 'do not disturb' sign up for the night.

No one dared knock and the Panzer tanks never moved.

Let me

say this again... for all his faults, Richard was

not stupid. Richard knew full well that Jasper

would likely encourage Henry to land in Wales.

It made perfect sense. However Richard was not

going to bet the house and fully commit to one

landing spot. Jasper's spies would warn Henry

if something was amiss and Henry would land

elsewhere. So Richard did the next best

thing... he shored up his support by handing out

lands, titles, and offices to men who had shown

loyalty to him in the past. Finally Richard

felt secure because he had extensive control over

south Wales.

|

| |

|

Richard's strategy should have worked, but it didn't.

Early in August, Richard was alarmed to find that

Henry's forces were moving through Wales unopposed.

Richard turned white with fear and anger. Just

how exactly did this come to pass?

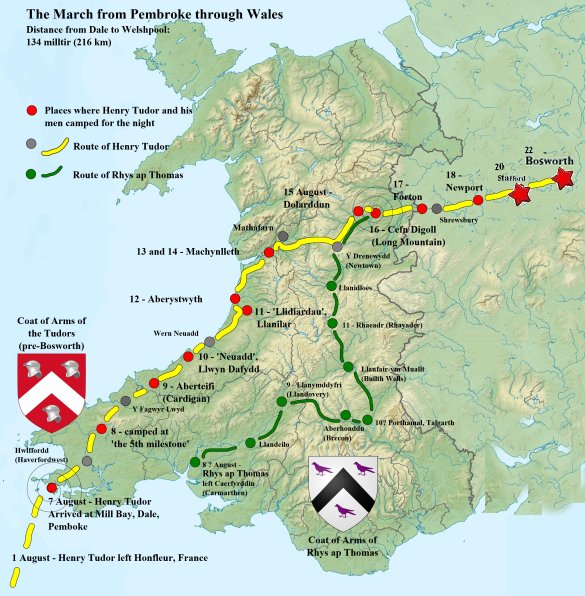

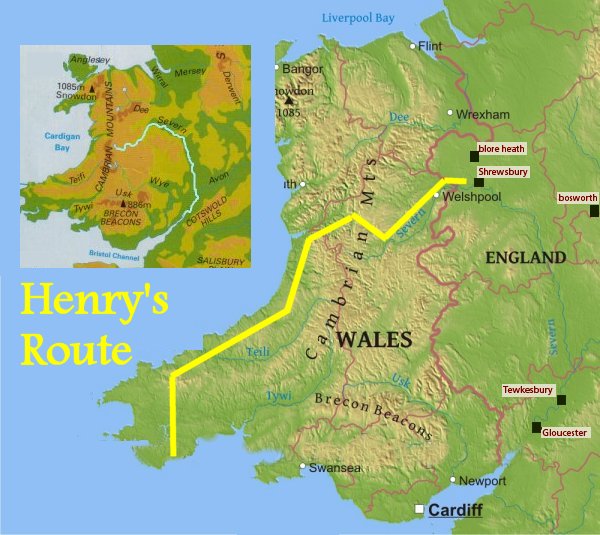

Mill Bay

had been chosen as a landing point because it was completely hidden from

view. No resistance was given by the cohort of

Richard's men stationed at Dale where Henry and his

men spent the first night. They completely

failed to keep the invader at bay by the bay.

In the

morning Henry marched to Haverfordwest, the county

town of Pembrokeshire. His men were received "with

the utmost goodwill of all". Welshman

Arnold Butler met Henry in Brittany and

announced that "the whole of Pembrokeshire is

prepared to serve him!"

Richard's lieutenant in South Wales, Sir Walter

Herbert, failed to move against Henry. Two of

Herbert's officers, Richard Griffith and Evan Morgan,

deserted to Henry with their men. The next man

to face Henry was Rhys ap Thomas, the leading figure

in West Wales.

Richard had appointed Rhys

Lieutenant in West Wales for his refusal to join

Buckingham's rebellion. Did Rhys ap Thomas

stop Henry? No, he defected to Henry's side

and brought with him many men.

So far,

Henry had been greeted warmly at every stop he made.

Henry was seen as the great Welsh champion.

The importance of Henry's Welsh blood and ancestry

should not be underestimated. Welsh support

would prove critical to Henry.

So far,

every single

man in Wales that Richard had rewarded for their loyalty

had welcomed the invasion force with hugs and kisses.

Richard

had just been given his first hint things weren't

exactly working out as planned.

|

|

Geography

There is

a very cynical saying that War is God's way of

teaching people Geography. So let's use the

War of the Roses to learn a little bit about Great

Britain's geography.

Off the

top of your head, what do you suppose Wales and

Scotland have that England doesn't have?

C'mon, this shouldn't be too hard to guess.

(Hint: It's big.)

Next

question. What did the Romans leave behind

that the English found particularly useful?

Next

question. Here in America, what place is

called the Gateway to the West?

Next

question. What place in England is known as

the Gateway to the Midlands? (Hint: unless you

are from Great Britain, you are not expected to know

this answer.)

Next

question: Given what you know about the

Gateway to the West, what do you suppose the Gateway

to the West and the Gateway to the Midlands have in

common??

Last

question: What geographical feature doomed Margaret

of Anjou at the Battle of Tewkesbury? (Hint:

it's on this map.)

Quit

your bellyaching. Hey, I gave you a map!

Figure it out.

|

|

Over My Belly

So what

Big Thing do Wales

and Scotland have that England doesn't?

Both Wales and Scotland are extremely mountainous while England

is relatively flat. Over the centuries, the

Welsh and the Scots have used those mountains as

defensive barriers to keep the English out. As

we look at the map, we see the only routes into

Wales are valleys formed by the rivers... unless of course

someone cheats and attacks using the sea.

By now,

we also have a pretty good idea who won the looming battle.

This, of course, takes away

much of the suspense. But Henry and Richard

had no idea of the outcome. They were both on

pins and needles. Richard was upset that Wales

had welcomed Richard with open arms, but he was not

entirely surprised. After all, Wales was

Henry's turf.

Okay, so

Wales had not panned out, but Richard

had another ace up his sleeve. Pretty soon

Henry would be on Richard's turf. Let's see

what happens then.

Henry

had a lot on his mind. Richard's army was

bound to be much larger, better

equipped, and better prepared. Richard knew

the territory well and would surely stake out the

finest ground to mount his defense. As Henry's

army trudged north, they used an ancient Roman road

that cut through the mountains using a valley formed

by the Severn, England's longest river.

|

| |

|

Once

Henry's army left the mountains of Wales, they

continued along the Roman road until they came to Shrewsbury, the traditional gateway to the

English midlands. In a manner similar to

America's St. Louis, Shrewsbury was very important

because it had the only bridge across the mighty

Severn River for miles and miles. Henry was

about to learn the hard way that the English attitude

towards his invasion was much cooler than the rabid

Welsh.

Shrewsbury was Richard's ace in the

hole. It had two bailiffs, Roger

Knight and Thomas Mitton who had been in power for about

two decades. Both men had prospered under Richard

III, most notably from the failure of Buckingham’s

Rebellion. Mitton had not only received Buckingham’s castle, Shrewsbury’s tax bill was significantly reduced,

making Mitton very popular. Mitton fully expected to be rewarded for

standing up to Henry. Another castle perhaps??

Richard

had given Mitton the perfect excuse to deny entry. Richard

had scared the wits out of the countryside

people by warning that Henry's foreigners would rape

and pillage in revenge for what the Black Prince had

done to the French a hundred years earlier. The people of Shrewsbury had no desire

to see Henry's French mercenaries come in and

plunder their town. Therefore, when Henry

requested permission to march through the streets, Mitton made an odd reply – “over my belly!” – which

we can assume is another way of saying 'over my

dead body'.

|

|

Henry

could not afford to go around the city thanks to the

ever-swollen Severn River. Nor

did he wish to engage in a fight. Henry was

engaged in a public relations battle almost as

fierce as the coming fight.

Richard

had painted a dark picture of Henry as a desperate

outlaw who had no money to pay his troops.

Richard said Henry had promised his men that they could murder

and take what they wanted in repayment. Henry could not afford to

attack these people of Shrewsbury lest rumors of his

aggressiveness spread.

So Henry

retreated. At a nearby village, he composed a

letter to the bailiffs, promising that his men would

simply march through Shrewsbury peacefully and cause

no damage or harm. He respected the oath of

loyalty to Richard III and did not expect any of the

townspeople to break it. The letter accomplished

little. Mitton still said no and repeated his

phrase 'over my belly!'

Henry was

in serious trouble. If he couldn't get past

Shrewsbury, his entire campaign would come to a

total stand-still. Then to his surprise, the gates came

open. Henry barely believed his eyes.

The

arrival of Rowland Warburton had made a

huge difference. Warburton persuaded the

bailiffs to let Henry pass. And who was

Rowland Warburton? He was a guy who lived at Blore Heath.

Blore

Heath... where have we heard that name before?

As it turned out, Shrewsbury was 20 miles south of Blore Heath, one of the famous battle sites during

the War of Roses.

|

|

And who

exactly was Rowland Warburton? He worked for

Chief Justice of North Wales, a man who just

happened to live near Blore Heath. The Chief

Justice of North Wales had ordered the gates to the

town come open.

And who

exactly was the Chief Justice of North Wales?

None other than Sir William Stanley, Richard's

carefully-chosen appointee as Chief Justice of North Wales.

Yes, indeed, William Stanley was Richard III’s chief lieutenant

in this area.

Other than John Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, no

single man in the kingdom had received more land and

power than William Stanley. Richard was

counting on William Stanley to stop Henry at the

Severn and contain him so the king's army could come and finish the

invasion off. Surely Richard's

well-rewarded commander would hold the line.

Nope.

Henry received an invitation to visit William at his

manor. Henry was

served tea and crumpets with an offer of perhaps a friendly

cricket match out on the lawn. Rumors have it

that William and Henry had a pow-wow in the process.

Yes, the

English citizens were afraid of Henry and his

terrible reputation, but in this part of

the world, the Stanley name was all-powerful.

The Stanley name was impressive enough to sway

even John Mitton who no doubt saw his hopes for a

new castle go up in smoke.

Interestingly, John Mitton was a man who had a

well-known reputation for always keeping his

word, a very good thing to have in politics. As Henry crossed the bridge, John Mitton made a point to lay

down on the ground. To much fanfare and

hilarity, Henry politely stepped over the man's belly, thereby

allowing Mitton to

keep his oath. We now see why Mitton didn't

say 'over my dead body'. Smart man.

Henry was relieved to pass through, but shaken to

realize that his support among the non-Welsh

populace was not widespread. Indeed, the

lesson of Shrewsbury was repeated in next

town he marched through. Since the average

citizen did not recognize his claim to the throne,

Henry had little to celebrate. This campaign

was shaping up as another 'Buckingham Rebellion'...

a reckless, seat of the pants, make-it-up-as-you-go-along

operation observed by a lukewarm, apathetic

citizenry that preferred to sit this one out.

Henry

was very worried.

|

Loyalty and Betrayal

When the

news that Henry had crossed the Severn River reached

Richard, he knew that William Stanley had betrayed

him. Richard was consumed with bitterness at

trusting the man. Now Henry was only 50 miles

away. To hell with William Henry.

William Henry was a pipsqueak. It was his

brother Thomas Stanley that Richard was worried about.

Richard was surely doomed if Lord Stanley opposed

him. Lord Stanley had been invaluable in

putting down the Buckingham Rebellion. But

could Richard count on Stanley again??

One

month earlier, an unsettling event had taken place.

In July 1485, about three weeks before Henry Tudor

landed, Thomas Stanley had sought permission to

leave the court and return to his northern estate of

Lathom in Lancashire. Stanley said he was

going to visit

a relative. The

king was no fool; Richard

allowed Stanley to leave London but

asked that

George, Stanley's son and

heir, remain behind.

Richard

made his request very politely... 'Lord Stanley,

we need your son to stay behind to fill your place

on the Council'.

But

everyone understood that George Stanley, 25, was

being kept as a hostage to ensure Thomas Stanley's

continued loyalty.

Now as

Henry moved through the English countryside, Richard

had not seen Thomas Stanley in over a month.

Considering William Stanley had just betrayed him,

Richard must not have been feeling too sure about

Thomas Stanley either. Nevertheless, Richard reassured

himself that George, also known as Lord Strange (no,

I am not making this up),

remained in

his household to assure his father’s

good behavior.

Surely no father on earth would risk his son's life

to betray his king.

Let

us ask what might be going through Lord Stanley's

mind as the two armies grew closer. Thomas Stanley had a decision to make.

Lord

Stanley had gained a reputation of remaining neutral

and not supporting any particular side in a battle

until he was absolutely positive which side would

win. Even then, the chances of him involving his

army were, to an extent, unlikely. Though this

strategy does not seem to an honorable

one, it gained the Stanley family more friends than

enemies. Lord Stanley had shown he was

master of taking advantage of any sort of

situation.

Is it

possible to grow stronger by sitting idle??

Thanks in large part to Stanley's odd fence-straddle

strategy, Stanley had the largest private army in

England after the King himself. And why was

that? There had been 30 years of fighting.

All the great Houses of the land had been decimated

by the civil war... House of Neville, House of Beaufort,

House of Percy, House of Stafford, House of Howard,

and House of York.

Did you

notice the similarity to the Game of Thrones?

House Stark, House Arryn, House Harrenhal, House

Lannister, House Durrandon, House Gardener, House

Martell. But Game of Thrones had seven houses

and the War of the Roses only had six. Or did

I miss someone? Hmm. Maybe the Reader

can help me. Can you think of a Seventh House?

As it

turns out, yes, there were Seven Houses in the War

of the Roses, but one of the Houses had never known

serious losses... because it never fought.

The

House of Stanley was virtually intact since the

start of the Wars. Lord Stanley enjoyed huge popularity

at home because he never risked his men's lives

unnecessarily and he kept his homeland out of the

fighting unless it was obvious he could win with

little risk.

When it came to 'Loyalty', as leaders go, one

could imagine Lord Stanley enjoyed the most

popularity of any leader in the country.

Unlike Richard, Stanley's men stood firmly behind him

because they knew he was the smartest Lord of all.

With

leadership comes responsibility. Lord Stanley

had a choice between King Richard and a young man

who just happened to be the son of his wife.

One would imagine the temptation to support his wife

and his stepson would be strong. But Stanley

had other factors to consider. For example,

which of the two men, Richard or Henry, would be the

best leader for the country?

What is

interesting about Stanley is he might actually think

in terms larger than simply his own personal gain.

If it came down to what would benefit him

personally, no doubt the greatest gain would be to

have a stepson as king. On the other hand,

Stanley had never met Henry. His only

knowledge of the boy had come from his association

with the lad's mother. In this case, one has

to recall Stanley's curious decision to back Richard

over his wife during Buckingham's Rebellion, a

decision which baffled many.

Right

now the life of Stanley's son George was at stake.

Stanley was forced to deal with this implicit threat

to his son's life. There is a difference

between serving a man out of loyalty and serving a

man out of threat. Loyalty is difficult to give

when there is a sword pointed at one's child.

Compliance, perhaps, but not loyalty. This was not the first time

Richard had threatened Stanley. No doubt

Stanley still remembered the day two years

earlier when Richard had his men seize Stanley and accuse him of plotting against him

(the Hastings situation).

That was the kind of memory that does not tend to fade away.

So, yes,

Stanley obeyed Richard out of necessity, but it

would be difficult to imagine Stanley felt any

loyalty to Richard, especially not after seeing the

head of his colleague Lord Hastings roll without

need. As much as anyone in the kingdom,

Stanley had witnessed first-hand how Richard had

usurped the crown with cold-blooded assassinations

and lies about the legitimacy of Edward's children.

One can imagine Lord Stanley felt little respect for

King Richard.

If I may

offer my own observation, I doubt seriously Lord

Stanley was on the fence as the battle brewed.

I base my decision on several factors. The

main fact is that if Richard won, all of Margaret's

lands would stay with Richard upon Lord Stanley's

death. Stanley would rather keep those lands

in the family. Therefore it was very much to

Stanley's advantage to back Henry... but not show

his hand in the process.

•

There was a report that

suggested Lord Stanley was the man who

tipped off Henry there was a plot against him in

Brittany.

•

There was a report that

hinted Lord Stanley had helped convince Sir

James Blount, captain of the Hammes prison in

Calais, to

oppose Richard and set Lord Oxford free at Hammes prison. After

Blount changed sides, Lord Oxford escaped to join Henry Tudor in Paris.

Understandably, this upset

Richard no end. To begin with, the

Oxford incident was indicative of the growing lack of loyalty to

his

regime. But even more important was that Henry finally had

an experienced general to lead his army.

•

When Richard received reports early in August that

Henry Tudor had crossed the corner of North Wales

unmolested, he knew for a fact that William Stanley

had betrayed him. Indeed, by opening the door

at Shrewsbury, Sir William had effectively

cleared the path for Henry Tudor to continue his

invasion. Knowing the Stanley brothers' penchant

for teamwork, it is unlikely William would have

done so without his older brother's approval.

•

In the week prior, Lord Stanley

disobeyed a direct order from Richard to bring

men to join him on the battlefield. Instead Stanley

claimed 'illness'. Poor Stanley, he

was too unwell to answer his King’s summons.

This meant Stanley would not bivouac with

Richard's army. However, Stanley did

promise to meet Richard on the battlefield.

•

One week prior to

the battle, Lord Strange tried to escape from

Richard, but was caught. No doubt Lord

Strange knew his father’s intentions were to

back Henry. If that was the case, then

Strange must have known his own life was likely

forfeit. His actions suggest Strange was

scared for his life and wanted to save his own

neck.

Under pressure, Lord Strange admitted that both

he and Sir William had been plotting with Henry

Tudor. However, Lord Strange swore he

had no idea what his father intended to do.

Lord

Strange was probably telling the truth. No one

ever knew for sure what Lord Stanley was thinking.

My guess is that Lord Stanley had one more question

to ask before he made up his mind... what kind of king would Henry Tudor make?

Lord

Stanley had asked his brother William to conduct an

initial interview at Stafford. Apparently Henry

passed his first audition since he was granted a

follow-up interview with both William and his brother, Lord

Thomas Stanley. This took place at Thomas

Stanley's camp in Atherstone two days before the

big battle. Richard's army camped atop a large

hill near the town of Bosworth. Atherstone lay six miles

to the

southwest.

Oddly

enough, after the interview Henry still wasn't sure where he

stood. Legend has it that Lord Stanley

assured his stepson of eventual support. Of course,

we all know promises can be easily broken,

especially promises made by Lord Stanley. All

Henry knew was that neither man had committed to fight with

him. Henry's mother had warned him the Stanley brothers were rumored to

deliberately take opposite sides during a conflict.

That way one Stanley would always win no matter what

the outcome while the loser would immediately pledge

undying allegiance to the winner... until the next

battle of course. People

were still trying to figure out how it was possible

that the Stanleys had backed Richard during the

Buckingham Rebellion. Thomas Stanley had to

know his wife Margaret was involved with the rebels,

so whose side was Lord Stanley really on?

Buckingham's Rebellion had been

a perfect example of a situation where either way

the Stanleys would win. If the Rebellion

failed, the Stanleys had backed King Richard.

If the Rebellion succeeded, Lord Stanley would tell

Margaret Richard had been at his side and it was too

risky to show his hand. No doubt Margaret would

then put in a kind word with her nephew Buckingham

or her son Henry.

The

English had seen this before. They

called Lord Stanley a 'trimmer', someone who

adapts his positions to match prevailing

political trends for personal advancement. In

other words, a trimmer 'trims' his sails to take

advantage of both the wind and the 'win'.

A clever phrase indeed and quite apt in this case.

Henry

may have been kept in the dark, but Richard was

pretty sure that Lord Stanley's heart was with

Henry.

| |

|

|

| |

|

Rick Archer's Note: Here

again we have an odd situation being

reported from Richard's point of view.

All the websites said pretty much the

same thing, 'Richard kept George as

hostage.'

However, I felt

suspicious.

I began to wonder if

this was Stanley's idea,

not Richard's. If one looks at

this from Stanley's point of view, this

hostage situation gave Stanley a

face-saving reason to stay neutral.

Curious, I nosed

around to see if anyone else was

suspicious about Stanley's

detached attitude towards his hostage son George.

A man named Richard P. McArthur writing for the

Richard III Foundation

appeared to agree with me:

"Could the idea of using Lord Strange as hostage

been Stanley’s? Richard III seems to have

asked no one else for hostages. The gambit would

be excellent for inducing Richard to allow

Stanley to be out of range of Richard’s

immediate power. Richard could probably be

counted on to be very hesitant in punishing

Strange. The fact that his son was in

Richard’s hands would also serve Thomas Stanley

as an excuse to Tudor for a lot of

procrastination."

Mr. McArthur

suggested that Lord Stanley was

secretly pleased by the hostage situation.

After all, it gave him the perfect excuse to tell

Henry, Margaret, and Richard 'why' he would sit the

battle out... which is probably what Stanley

wanted to do all along. Why risk

making real enemies when one can merely

irritate them instead?

Was Stanley really willing to deliberately risk his

son's own life? It is chilling to believe he thought

up the hostage situation on his own as a clever excuse,

but I would not put it past him.

"Gee,

Henry, I want so badly to send my men out on the

field to face that monster Richard, but he

has my son!"

"Richard,

you can count on me. After all, I knelt

before you and pledged my oath. In

addition, of my own choosing, I offered

you my son as a firm sign of my good will!

You will see me bring my army to the field, I

promise."

Earlier I made this

point:

However, if

Richard won the coming battle,

Stanley was in big trouble...

unless Stanley could find a way not

to oppose Richard. Stanley

had to find a way to help Henry and

stay neutral at the same time.

Now how does someone do that? I

guess we will find out when the time

comes.

We just got our

answer... Stanley had used his own son

as collateral.

|

| |

|

Countdown to Battle

Like his brother, William Stanley also stayed

non-committal. Although his actions in Wales

and Shrewsbury had already labeled him a traitor,

William Stanley would not obligate himself to unite

his force with Henry's. On 22 August

William pitched his camp near Atherstone next to his

brother. This spot was some distance from both the main

bodies. Their post at Atherstone formed a

triangle of sorts with Richard's camp to their right

on the other side of a marsh and Henry's camp to

their left. Henry and Richard knew this

meant the Stanley brothers would not

publicly declare their support for either man.

On the

eve of the battle, Richard was angry. Lord

Stanley had 3,000 followers and his brother William

had another 2,000. Lord Stanley had promised

to fight with him. Well, this was put up or

shut up time. King Richard sent Stanley a

message that unless he moved his forces to align

with his, he would put Lord Strange, the hostage, to

death.

Lord Stanley sent a terse reply "that he might do

so at his pleasure."

Stanley had defied his order. Richard

immediately lost his temper and ordered Lord Strange

to be executed at the start of the battle tomorrow.

Then he calmed down and decided it would be wiser to

wait to see what Stanley did in the morning.

Richard sent Strange to a tent under heavy guard.

(Rick

Archer's Note: Stanley appeared to

be betting that Richard was a rational man.

He expected Richard would realize that to kill

the hostage too early would cost him his

leverage. But what kind of man has the

guts to make that kind of bet?)

Truth be

told, Richard was less troubled by Stanley's

waffling than Henry. After all, Richard would

have been content if the two Stanleys simply stayed

out of the battle whereas Henry was desperate for

their support. Richard’s army had larger

numbers and far more confidence.

Furthermore, Richard

did not even have to win. All Richard had to

do was avoid being killed. In addition to his

12,000 men, Richard had reinforcements waiting for

him in Nottingham

and Leicester. Richard could lose today and

fight another battle tomorrow. Not Henry.

This coming battle was his only shot. With

Richard sitting pretty up atop his hill, he smiled

in the knowledge that Henry must be terrified.

Richard

was correct.

Henry was indeed panic-stricken on the eve of the

battle.

If either

Lord Stanley or William Stanley backed Richard, it was

all over.

If Lord Stanley and William Stanley

decided to sit it out, then Richard still had the superior

forces and the experience.

Henry

believed his only chance of victory would come if

the Stanleys would fight on his side. But that

seemed unlikely. In his private interview

shortly before the battle, Henry attempted to win

them over, but he was apparently unsuccessful.

Meanwhile, he knew that Richard held Stanley's heir

hostage. How could Henry hope that Lord

Stanley would defy Richard in this circumstance?

Henry was in a near-hopeless position. Without

Stanley, his badly-outnumbered, ragtag army stood

little chance of victory. His men seemed just

as nervous as he was. Their loyalty to him was

tenuous at best. If the battle started poorly,

no doubt the weak of heart would flee on the spot

and save their own skins. The battle could be

over the moment it started.

At this

point, Henry despaired that it was hopeless.

Even Margaret is suddenly struck by just how long

the odds were. No doubt she was terrified of

losing her son on the battlefield.

Seeing her son so despondent, Margaret Beaufort

decided to intercede. Riding over to Lord

Stanley's camp, she confronted her husband and

begged him to fight.

"Husband, I implore you to fight at my son's side

tomorrow."

"You

overlook that this action will cost me the life

of my son and heir. I will not abandon my

son for yours."

"“Your

son will be honored as a man of courage, the first

to fall in Henry’s service,”

Stanley's reply was quite fascinating.

"Margaret, I do not find this comforting.

Think about what you have asked.

You have asked me to sacrifice my son so that your

son will live."

"But Henry has a divine right to rule!"

Stanley:

"If that is truly the case, then you should have

nothing to worry about."

|

|

The Ghosts of Richard Pay Him a Visit |

| |

|

|

|

Richard

was feeling good about his chances when he went to

bed. However, William Shakespeare suggested

Richard was having nightmares.

If one

believes Shakespeare, Richard had murdered

enough victims to fill a cemetery.

Through

the centuries, Shakespeare’s

dark depiction of Richard has

remained unshaken.

No one who has seen Richard III has

any trouble visualizing Richard as a

deformed Machiavellian

who betrays his dead brother,

murders his nephews to gain his crown and poisons

his wife to pursue his voluptuous niece.

As a malicious, deceptive and bitter usurper who seizes

England’s throne by nefarious means,

Shakespeare’s

Richard revels in his own villainy.

In his famous “Now is the winter of our discontent”

speech, Richard

shamelessly proclaimed:

“I am determined to prove

myself a villain.”

|

|

| |

|

The

problem for the audience is that Richard is so damn

interesting. Richard is an undeniably charming and complex

figure who sucks in the audience with his immoral logic

and dazzling wordplay. The audience

shakes its collective head in astonishment that

someone this shrewd had to resort to such foul means

to get what he wanted.

But then we stop liking

Richard thanks to a brilliant Shakespeare scene...

Richard's nightmare. In this nightmare,

Richard’s sins come back to haunt him – quite

literally!!

According to William

Shakespeare, on the eve of

battle, Richard was haunted by the memory of his

crimes. Shakespeare

has found a clever way to help us recall each of

Richard’s murder victims. The

specters of these victims appear one by one in a roll call of ghosts

who

visit Richard in his sleep.

They each point to Richard

and claim to have been murdered by

the king.

| |

|

•

Prince Edward of

Westminster

•

King Henry VI

•

George, Duke of Clarence

•

Earl

Rivers (Anthony Woodville)

•

Richard Grey

•

Thomas Vaughan

•

Lord Hastings

•

The Princes in the Tower

•

Duke of Buckingham

•

Queen

Anne Neville

|

|

|

| |

The

king is visibly shaken

by the ghosts of his murder victims. One by one, each ghost

recalls what Richard has done to them and condemns

him to death on the battlefield. The

ghosts parade

past Richard and chant "Despair and die!"

Smug and

confident earlier in the night,

Richard is now struck by doubt.

Forgetting the glee he

formerly took in his wrongdoing, he suddenly lacks

conviction about the wisdom of his actions.

“O no, alas, I rather hate

myself for hateful deeds committed by myself.... I am a

villain.”

At one point, there were so many ghosts, the stage

barely has room to accommodate them all. There

was also a strange twist in the dream scene.

Shakespeare forced Richard to stand by and watch as

the ghosts leave to pay Henry Tudor a visit.

The ghosts offer

encouragement in the upcoming battle. Richard was

understandably quite shaken

when he awoke.

Shakespeare

believed what goes around comes around.

Shakespeare knew the audience would take

satisfaction in the thought that Richard's

evildoings would come back

to haunt him, first in his

dreams, then on the battlefield. At

heart, most people in Medieval England yearned for

justice and fair play. The rest took part in

the War of the Roses.

|

|

The Battle of Bosworth |

|

| |

|

Battle Positions

|

|

|

|

|

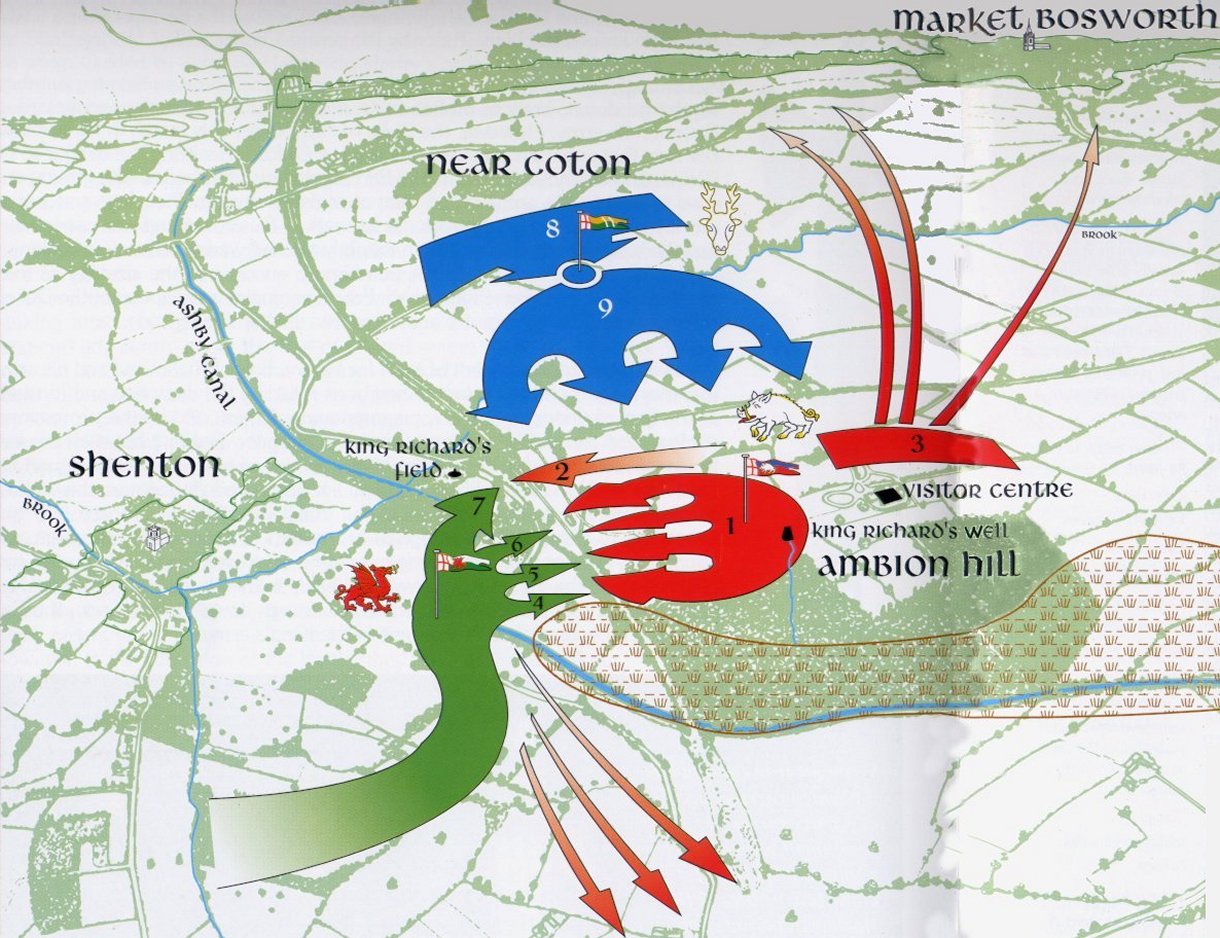

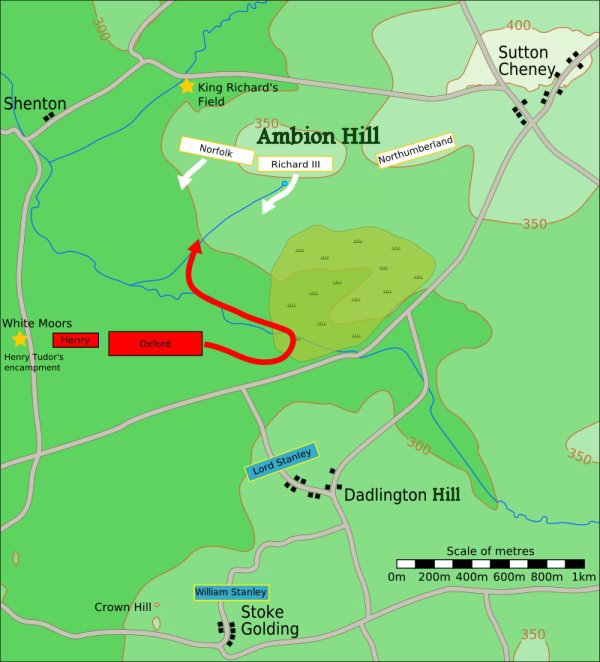

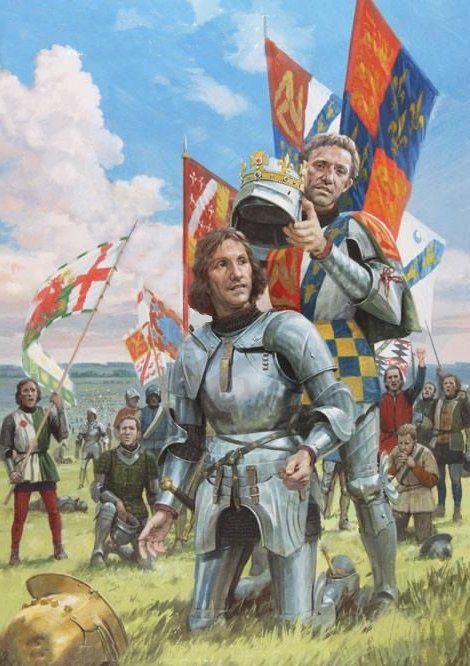

On the

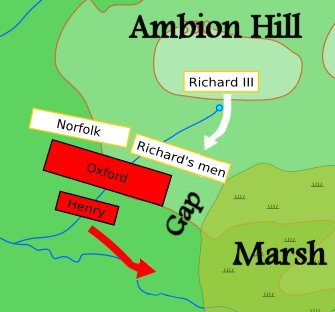

morning of the battle, 22 August 1485, four armies

converged on a field south of Bosworth Market, 13

miles west of Leicester: Richard, numbering 12,000;

Henry, numbering 5,000; and two Stanley

armies, some 5,000 when combined.

Richard

had expected to have an even larger army. Richard

had called the lords of the realm to assemble under

his banner at Leicester on the 16th of August.

But many

of his vassals either failed to answer the royal summons

or conveniently got stuck in transit.

Nevertheless Richard was pleased to note his force

still greatly outnumbered his opponent. His

nightmares aside, Richard was quite confident of

victory as the battle began.

The

chief lords who did join their king were John

Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and Henry Percy, 4th Earl

of Northumberland.

John Howard

had been Richard's right hand man from the moment

Richard made his rise in 1483. Now here at

Bosworth, Howard was Richard's most trusted general. Norfolk commanded the Yorkist Vanguard to Richard's

right. The men under Richard's control had a deep, soupy marsh on

the

left to use as a defensive measure.

Henry Percy

was in the rear with 7,000 reserves. Richard had

a bad feeling about Percy. Richard had paid a

high price to win Percy's loyalty, but today this

man was worried about something.

Since Richard

had so many men, the field was not wide enough for

everyone to fight

at once. So he placed a considerable force in

reserve under Lord Northumberland. Just to be sure,

Richard placed a close watch on Percy when the

battle started. Richard didn't want Percy to

turn his own men on him. Richard was sick and

tired of people betraying him.

As

expected, the two Stanley armies moved into neutral

positions on a hill. They stood side by side

about half a mile apart.

|

|

| |

|

Henry Tudor took the field with a

motley crew. Among his 5,000 men were roughly 1,000

French, 2,000 Welsh, 500 Scots, and 1,000 dispossessed Lancastrian exiles

plus a few York loyalists who

couldn't stand Richard. In other words,

Henry's army was comprised of everyone who hated the

Yorks plus everyone who hated the English... French, Welsh, and Scots.

Henry

was outnumbered 2 to 1. However, with half of

Richard's army held in reserve, the numbers were

roughly equal on the front line.

Henry was

well aware of his military shortcomings, so he put his friend John de Vere, Lord

Oxford, in charge of the planning. This was

Oxford's chance to redeem himself. Fourteen

years earlier, Oxford should have been the hero at the

1471 Battle of Barnet. Instead, Oxford had

lost

control of his men who decided to begin partying before the

battle was over. Amazingly, the vastly

superior Lancaster side lost the

battle. Warwick was killed and Edward IV regained

the throne. Given this shocking turn of

events, Lord Oxford's guilt must have been immense. Oxford

had disliked Yorkist King Edward, but he absolutely despised

King Richard. Oxford was burning to put this man

down once and for all.

Neither

Richard nor Henry moved to the front.

Henry, unsure of his fighting ability,

remained in back of Oxford's vanguard surrounded by

elite Welsh bodyguards. Richard

on the other hand was a warrior. He fully

intended to fight. However,

right now there were too many uncertainties... the Stanleys, Lord Northumberland, as well as Oxford's

initial strategy. Therefore Richard chose to stay up on the

hill where he could survey the situation.

Flanked by his own elite unit of mounted bodyguards,

Richard was content to let Norfolk take the lead.

The

battle unfolded when Oxford began advancing the Lancastrian

forces towards Ambion Hill in one body. His

right-wing was protected by the marsh. An exchange of

arrows and cannon fire followed. Richard had

more cannons, so Oxford decided to get closer to

Norfolk's men as the best protection from further

cannon shots.

|

| |

|

When

Richard saw Oxford advancing, he

ordered Norfolk to attack the enemy just after they

passed the marsh. Norfolk’s vanguard came down Ambion Hill

to

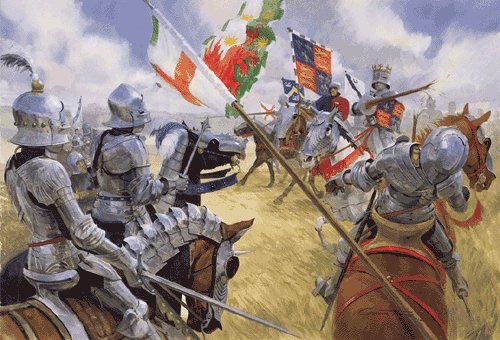

engage Oxford's force at the base. In the fierce melee that

followed, men hacked at each other in brutal

hand-to-hand combat using weapons such as the pole-axe,

hammer, battle axe, spear, mace, and long sword.

Norfolk's men were surprised when Oxford

suddenly moved his men into an

unusual V-shaped wedge. This wedge was a

favorite French offensive maneuver. During his

outlaw years, Oxford had

spent time fighting in France as a mercenary.

He

knew this formation well. In addition, his

cadre of French mercenaries was also quite familiar

with the technique. Hoping his opponent had

not studied recent French battle tactics, Oxford had

told these men in advance that he was planning to

use this maneuver.

Oxford placed two

banners in the ground, and encouraged his men to

form up between them in a V-shape. This created a solid

wedge of men similar to an arrow's point.

Norfolk had never seen this formation before. When Norfolk charged, he found

Oxford’s Wedge difficult to attack. Norfolk's

force was getting the worst of the melee, so Norfolk

risked his life trying to counter-attack. Bad

move. His risk failed and Norfolk was killed,

some say felled by Lord Oxford himself.

Richard had lost his best friend and finest ally.

|

|

| |

|

Historian Chris Skidmore discusses Oxford's French

connection.

HENRY TUDOR'S SECRET WEAPON: THE FRENCH

With too few English men to fight in his army,

Tudor had been forced to recruit trained

mercenaries from Normandy to fight for him.

These French forces seem to have been experts in

military warfare, and were quickly able to

establish "by the king’s shot the lie of the

land and the order of his battle". The

Burgundian Chronicler Jean Molinet wrote how the

French troops, led by Philibert de Chandee -

whom Henry VII would later reward with the title

Earl of Bath - ordered for Tudor’s force to be

reassembled, and "in order to avoid the fire"

and instead to attack the right hand flank of

Richard’s vanguard, that seems to have caused

confusion in the royal army. Richard’s vanguard

was broken and soon dispersed and the French,

according to Molinet, "obtained the mastery of

his vanguard". A letter written by a French

soldier shortly after the battle, described how

Richard was heard crying “These French traitors

are today the cause of our realm’s ruin".

|

| |

|

Richard was aware that Norfolk had fallen. However, the

advantage of numbers was still with Richard and the Yorkists.

The problem for Richard was that Norfolk's battle lines

began to disintegrate without Norfolk's leadership. Richard ordered

Northumberland to bring up his reserve and join

Norfolk's hard-pressed men.

To

Richard's stupefaction, Lord Percy either did not

get the message or refused to participate.

Historians argue to this day whether this was

treachery or simply an inability of Percy to find

room to maneuver his force around Richard’s force or

around the marsh to the left. There are those

who suggest the Lord of Northumberland may have had

a pre-existing understanding with Lord Stanley (who

else?).

Percy's

men claimed unable to cross the marsh,

but Richard didn't believe a word of it.

He felt betrayed.

Given Richard's earlier suspicion, Richard concluded

'Treachery' was the more likely answer.

Whatever the reason, the reserve forces did not move

and Norfolk's line was about to collapse.

| |

Historian Chris Skidmore discusses the

reports of treason.

ABANDONED BY THE EARL OF

NORTHUMBERLAND

With the collapse of his vanguard,

Richard would have expected that his

rear-guard, led by Henry Percy, the earl

of Northumberland, to provide reinforcements.

Instead the earl did nothing. One

chronicler was insistent that "in the

place where the earl of Northumberland

was posted, with a large company of

reasonably good men, no engagement could

be discerned, and no battle blows given

or received". Northumberland, Jean

Molinet observed, should have "charged

the French" but instead "did nothing

except to flee, both he and his company,

and to abandon his King Richard" since

he had already agreed a secret pact with

Henry Tudor.

Northumberland was a northern lord whose

own power had diminished over the past

decade as a result of Richard’s rise to

power. He had nothing to lose and

everything to gain from abandoning his

king. Other reports from the battlefield

suggest that Northumberland may have not

only left Richard to his fate, but

actively turned against him and "left

his position and passed in front of the

king’s vanguard", at which point,

"turning his back on Earl Henry, he

began to fight fiercely against the

king’s van, and so did all the others

who had plighted their faith to Earl

Henry". If this were the case, it would

explain why Richard had been heard

"shouting again and again that he was

betrayed, and crying ‘Treason! Treason!

Treason!’"

|

| |

Things

were getting desperate. Oxford's men may have been out-numbered,

but they had more hate in them than his own men.

Plus they had the momentum thanks to that strange

wedge formation. The Wedge was pushing

Norfolk's men back towards Richard's men in the

rear. Something had to be done to bolster Norfolk’s flagging forces.

What was Richard to do? Norfolk's line

was floundering, Northumberland

stayed mysteriously rooted to the spot, and Stanley

continued to defy

his order. Realizing it was up to him to save

this battle, Richard mobilized his own force down

the hill to fill the breech.

Richard

watched in horror as the battle was in danger of getting away from him. Richard's eyes

automatically turned to the two Stanleys.

There they stood with their 5,000 men positioned on Dadlington Hill

less than a mile away. Richard was

infuriated. That damn Thomas Stanley!!

Why didn't he fight?

Incensed that Lord Stanley

still refused to participate, Richard

sent three messengers to Stanley with a curt and

quite frustrated demand... "Order your men to fight

now or watch your son die!"

15

minutes later the messengers were back.

Richard anxiously asked them what Stanley had said.

Lord Stanley's reply was so

unbelievable, it became instant military legend.

"Tell

Richard I have other sons."

Furious

at Stanley's defiance, Richard ordered his hostage, Lord Strange,

beheaded. However, in the heat and confusion of battle,

the order was not carried out... probably because no

one wanted to carry out the order. Whether

Richard won or lost, after the

battle, Lord Stanley would undoubtedly seek the

identity of the executioner and have his vengeance.

Since Richard was too busy to see if his order had

been carried out, Lord Strange was never touched.

Lord Stanley

never budged an inch throughout the battle.

|

| |

|

Richard's Charge

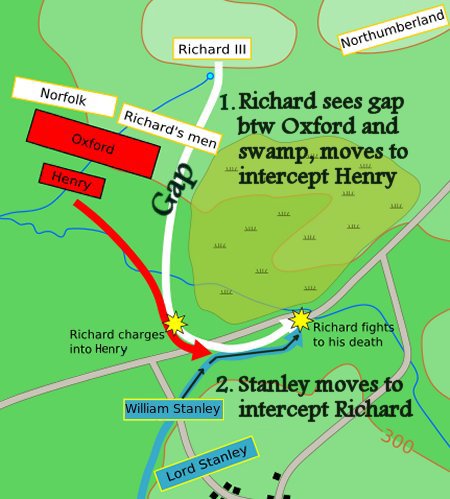

Henry

was feeling abandoned. Lord Stanley had

promised to help days earlier, but had yet to move.

This was bad news. Henry was still convinced

his army had no chance of victory against these

superior forces without Lord Stanley's help.

On the

other hand, he was encouraged by Oxford's

considerable success. Henry wasn't going to

give up without a fight. Seeing Richard's men

come down the hill about to attack Oxford, Henry

decided to advance his own men forward into the

battle to support Oxford's vulnerable right.

Henry moved his men to the right where there was an

opening between Oxford and the marsh.

Richard

could see that Henry was headed into the gap before

him. There were men fighting there, but

very few. No doubt Henry was moving to check the

advancement of the men Richard had recently sent