|

Creating the Canal 1

THE LOCKS and THE

HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN EFFORT

Written by Rick Archer

October 2011

|

|

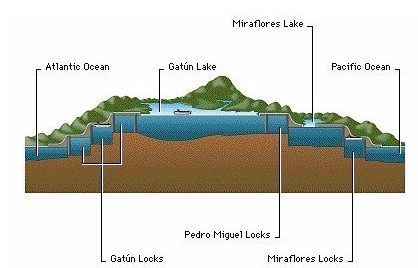

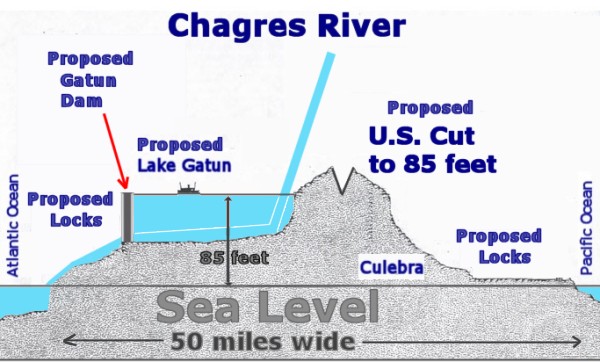

Lake Gatun rests at 85 feet above

sea level. The purpose

of the locks at either end of the Canal is to lift

a ship in stages up to the Lake at 85 feet or to lower

a

ship back down to sea level.

These locks

were one of the greatest

engineering works ever to be undertaken at the time.

Not until Hoover Dam did America undertake another project even

remotely approaching the Panama Canal.

|

|

|

|

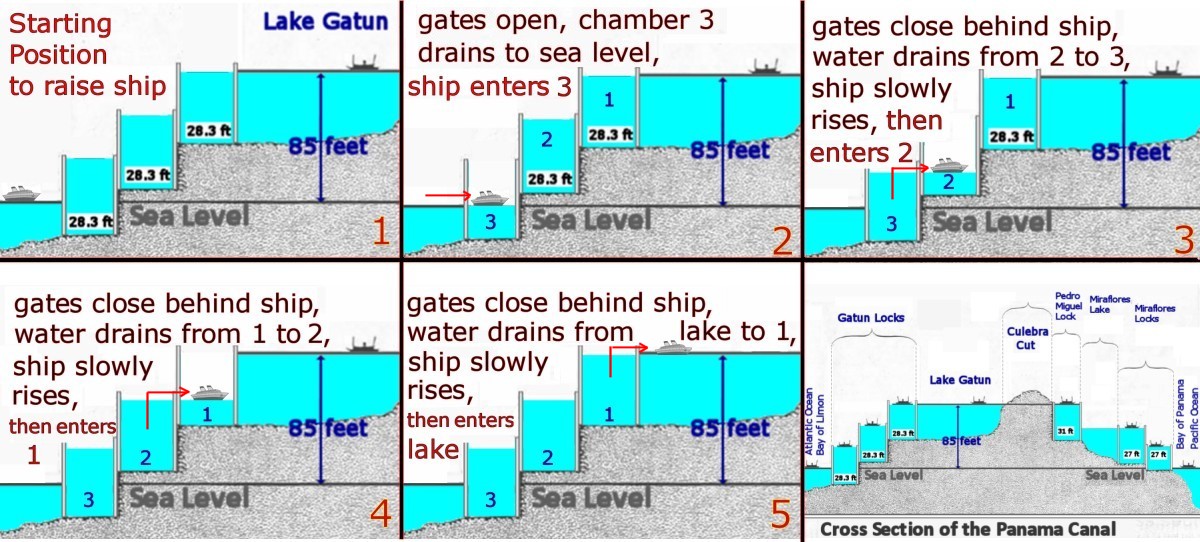

So how

do these locks work?

Back when you were a kid and you

played in the bathtub with toy boats, you

may remember your toy boats rose as the tub

filled with water and dropped when the water

drained. The ships in the Canal

may be very large ships, but they rise and

fall

exactly the same way. The locks

operate as giant bathtubs.

If you fill the chamber with water, the ship

automatically begins to rise. Or if

you drain the chamber, the boat will slowly

sink. It is all done by gravity.

Gravity makes the water drain.

No water in the canal is ever pumped

upwards.

The important rule is that

water seeks its own level. When the

water from one chamber is allowed to drain

into a lower chamber, gravity guarantees the

water will keep flowing until the water

level in both chambers is equal.

Then the water stops flowing of its own

accord.

There are drainage pipes inside

the concrete walls known as "culverts".

When these culverts are opened, water will

automatically drain out of the higher water

level to the lower water level until the

levels are EQUAL. A ship will

automatically rise or sink depending on

which chamber it is in. Once the water

level is equal in the two adjacent chambers,

the ship is free to float across to the next

chamber.

You may have noticed the ships barely fit

inside the water chambers. This is

deliberate. The more snugly the ship

fits in

the chamber, the less water is needed to

fill the chamber. Water is a valuable

resource here. Why waste it?

The limit to the size of a ship that can fit through the

Panama Canal is called "Panamax". In

the past 100 years, many ships have been

built that are simply too large to fit.

With this in mind, new locks are being built

right now that will be able to accommodate many of the

larger ships.

It looks like

there is no room, but there is

actually several feet of water on

either side of the ship inside the

chambers. To

keep the ships from scraping against

the walls, tugging devices known as

"mules" run on train tracks on both

sides of the ship.

These small trains

have steel cables attached to the

ship. The ship moves forward under

its own power, but the mules

guarantee the ship stays centered.

|

|

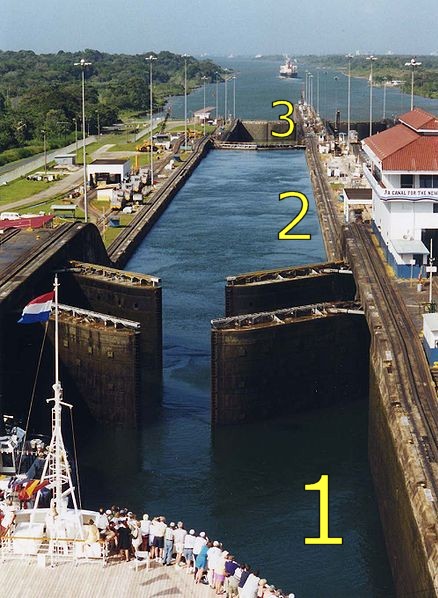

The lifting or lowering process is done in 3

stages on both ends of the canal. 85

feet is too much to do at one time.

The weight of the water would cause

unimaginable pressure against the iron

gates. By using three

stages to lower or raise a

ship, the combined weight of the ship and the water

is sufficiently reduced so there won't be too

much pressure on the steel doors.

This picture shows two sets of iron water

gates. The "double door" system

is used so if a runaway ship smashes against one set

of doors, the other set will still be able

to control the waters from breaking loose.

So far it has never happened, but it is a

good safety feature nevertheless.

Lowering a

Ship

Lowering a ship is easier to understand than

raising a ship. In the picture, a cruise ship is headed out to

the Bay of Limon. Chamber 1

has just drained down to the level of Chamber 2.

Since the water levels between Chamber 1 and

Chamber 2 are equal, the iron gates open to permit the ship to

slide forward into Chamber 2. Once the ship

is in Chamber 2, those same gates will close

behind the ship.

Chamber 3 up ahead appears empty. Once the

ship has moved completely into Chamber 2, the waters in Chamber 2 will

drain down into Chamber 3. The ship will

sink in Chamber 2 until the waters become equal.

Then it will float into Chamber 3.

Chamber 3 will then sink to match the sea level

to

allow the ship to leave.

Pretty ingenious system. But there is

a weak point. Yes, there actually is

an Achilles Heel of sorts. I'll let you think

about it for a while, then explain the

problem as well as the solution shortly.

|

|

So how do you make a ship rise by draining

water?

I don't recall

ever seeing my toy boats rise when Mom drained the bathtub.

So I was very curious to understand how ships are raised.

From what I gather, raising a ship is a four-step process.

I could describe it, but I think the pictures will do a

better job.

|

|

|

|

|

Water Concerns

The weakness in the system is water. There are six

locks total and each one is huge. Each canal lock measures

110 feet across and 1,050 feet in length, with solid steel

gates six feet thick.

Each passage through

the canal requires 52 million gallons of freshwater to float

the ship through locks. This means

nothing to someone not used to thinking in those terms, so

let's do it this way. An Olympic-sized swimming pool

holds 253,125 gallons of water. That means every trip

of a ship through the Canal requires filling 200 massive

swimming pools.

|

|

Whether a ship

rises or lowers at the Gatun Locks, either way the

water used in the process is eventually going out to sea.

The question is: does it rain enough to replace the water?

Back in the days before it was dammed, the Rio Chagres used to flow out to sea

all day long. So it is hard to imagine

much of a difference. However, now water has to go out

to the Pacific locks as well. In other words, the demand on

the water faucet known as the Chagres River has doubled.

Seeing the need to conserve water, in 1935 the U.S. built

Madden Dam up in the mountains to create Alahuela

Lake. This reservoir traps the Chagres waters

closer to its source. This lake has become an essential

element in making sure the canal has an adequate water

supply.

The lake has a maximum level of 250 ft above sea

level and can store one third of the canal's annual need.

For the time being, there's enough water.

However, changing climate patterns deforestation, and increased shipping demand at the

Canal has everyone in Panama

worried about the future.

|

|

|

|

How Long is the Panama Canal?

The exact length of the

Panama Canal varies

depending at which point you wish to use to start counting the

mileage. Many people just say 50 miles and leave it at that.

The time to cross the Canal is about 8-10 hours.

By comparison, the

Houston Ship Channel is roughly the same length. The big

difference is the Houston Ship Channel merely had to dredge the

bottom of Buffalo Bayou to create a sea level route deep enough for

big ships to enter. Rumor has it that the Panama Canal is a

bit more complicated.

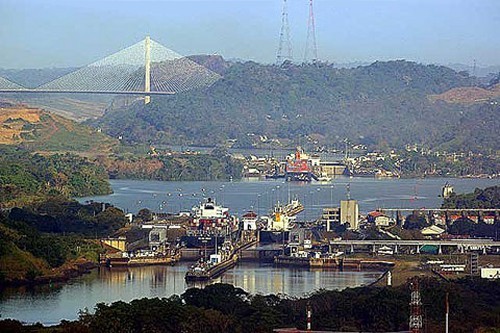

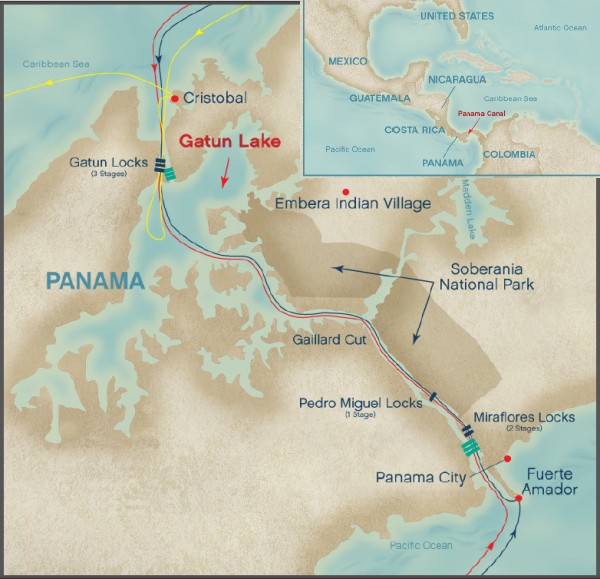

On the right you see the

Miraflores Locks, Miraflores Lake, the Pedro Miguel Locks, and part

of the

Culebra Cut channel including the Centennial Bridge. Those towers

in the background are at the Continental Divide.

This picture shows the

water at three distinct levels. The Panama Canal is an

engineering marvel that just boggles the imagination.

|

|

Distance Chart

The following description assumes you are entering from the Atlantic

side of the Canal. Reverse it if you are entering from the

Pacific.

- Limón Bay

(Bahía Limón), a huge natural harbor on the Atlantic side,

provides anchorage for ships awaiting passage. It runs

5.4 miles from the outer breakwater to the Gatún Locks. An

extra 2 mile channel forms the approach to the locks from the

Atlantic side.

Total: 7.4 miles

- The Gatún Locks,

a 3-stage flight of locks 1.2 miles long, serve to raise

ships from sea level up to the level of Lake Gatún or lower

ships coming from the Pacific direction.

Total: 8.6

miles

- Lake Gatún,

an artificial lake formed by the building of the nearby Gatun

Dam, carries vessels 15 miles

across the isthmus using pretty much the same channel originally

created by the Rio Chagres.

Total: 23.6 miles

- The Chagres

River (Río Chagres), a natural waterway enhanced by the

damming of Lake Gatún, runs east-west

5.3 miles between the

Culebra Cut and Lake Gatun.

Total: 28.9 miles

- The Culebra Cut

(aka Gaillard Cut) slices 7.8 miles through the Continental

Divide at an altitude of 85 feet and passes under the

Centennial Bridge just before reaching the Pedro Miguel

Lock.

Total: 36.7 miles

- The single-stage

Pedro Miguel Lock is 0.9 miles long. It is the first

part of the descent (or ascent) to the level of the Pacific

Ocean. This lock has a drop of 31 feet. It takes a

ship from

85 feet level down to the level of Miraflores Lake.

Total: 45.6 miles

- The artificial

Miraflores Lake is the next stage. Resting at an elevation

of 54 feet above sea level, it is

1.1 miles long.

Total:

46.7 miles

- The two-stage

Miraflores Lock system, including the approach wall, is

1.1

miles long. Each stage

raises or lowers a ship 27 feet. So the combination adds up to a total lift or drop of 54 feet at

mid-tide.

Total: 47.8 miles

- From the Miraflores

locks, ships travel at sea level

8.2 miles down a channel to the

Gulf of Panama on the Pacific side, passing under the Bridge

of the Americas in the process.

Total: 56 miles

|

|

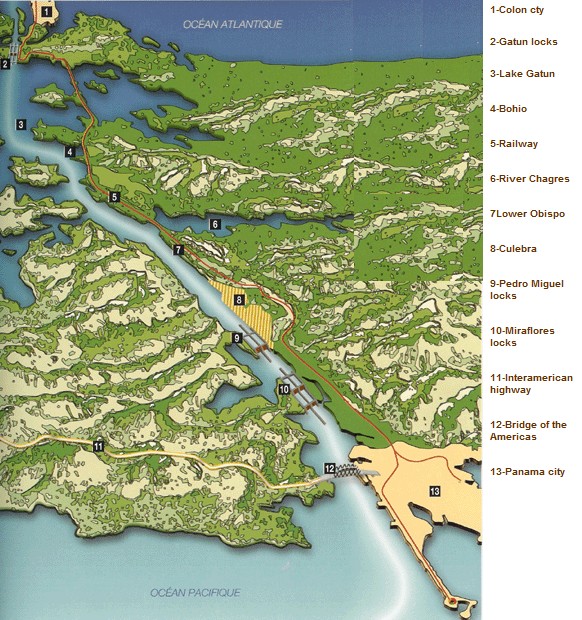

The Panama Canal

is called a "Lake and Lock" system. It is essentially a river

(Chagres) and a lake (Gatun) flanked by locks on either end. Here is a

detailed

look at the various sections.

Colón (1) is a

sea port on the Caribbean Sea coast of Panama. Colón overlooks

the enormous Bay of Limon which serves as the Atlantic

entrance to the Panama Canal.

At the back

of the Bay of Limon lies the Gatun Locks (2) which link

the Bay of Limon to

Lake Gatun (3)

Once the ships reach

Lake Gatun, they float for 15 miles down a channel that was

once the

Rio Chagres before the lake was created. Bohio (4) is considered the end of

Lake

Gatun and the start of Rio Chagres.

The upper part of the

Chagres River (6) merges with the Canal at a town known as Gamboa (6).

The Obispo (7)

was once a short river that served as a tributary of the Rio

Chagres. The Obispo River was dredged out and used to connect

Gamboa to the Culebra Cut (8), aka the "Big Ditch".

The ship reaches the end of its journey 85 feet above

sea level at a place known as the Pedro Miguel Locks (9).

These locks connect the Culebra Cut to Miraflores Lake.

The Pedro Miguel

Locks lower the ship 31 feet

down to

Lake Miraflores. One mile later they reach the Miraflores Locks (10).

At this point, the ships

are now lowered again

through the Miraflores Locks to sea

level. The ship passes under the

Bridge of the Americas (12) at Panama City

(13).

|

|

History of Events Leading to the Creation of the Panama Canal |

No tale of the Panama Canal can possibly be complete without a study

of the factors which led to the building of the Panama Canal.

There had been a strong desire to have a

canal run through the Central American isthmus since the early 16th

century when the Spanish dominated the region. The

Spanish long sought to build a canal to achieve an easier route to

access their colonies on the Pacific side.

The

Spanish government had plans in place, but

no action was ever taken.

Interest intensified to build a canal when

gold was discovered in California in 1848. American settlers,

looking for land and gold, wanted a quicker route than the

arduous and often dangerous trek across continental U.S.

The American government

was also interested, but for a military reason. The Canal

would be important for security reasons. The military did not

like having its navy divided from one ocean to the other.

|

|

|

|

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine

is a U.S. policy that warned any further efforts by European

countries to colonize land or interfere with states in the Americas

would be viewed as acts of aggression.

The doctrine was

introduced by President James Monroe on December 2, 1823, when he was enraged at the

actions of various European countries taking place in the Caribbean

and Latin America.

The Monroe Doctrine

asserted that the Americas were not to be further colonized by

European countries. In turn, the United States promised it would neither

interfere with existing European colonies nor meddle in the internal

concerns of European countries.

The Doctrine was issued

at a time when many Latin American countries were on the verge of

becoming independent from the Spanish Empire. The United States,

reflecting concerns raised by Great Britain, ultimately hoped to

avoid having any European power take over Spain's colonies.

The British worked hand in hand with the United States in upholding

the doctrine. This was the start of the special

relationship between England and the USA that remains today.

|

|

The Monroe Doctrine became a defining moment in the foreign policy

of the United States. It basically told everyone that the USA

was now in control of the waters on this side of the Atlantic

whether Europe liked it or not.

The Monroe Doctrine remains one of our country's longest-standing tenets.

It has been invoked by several U.S. presidents, including Theodore

Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and John F. Kennedy (Cuban

Missile Crisis). One recent use of the doctrine was in 1983.

Ronald Reagan used it to justify sending marines to a small

Caribbean island nation known as Grenada to put down a communist

overthrow of the government.

Monroe surely had no way to envision that his

Doctrine would persist with only minor variations for the next two

centuries. Its primary objective was to free the newly independent

colonies of Latin America from European intervention and control

(thus ensuring US national security). However, the doctrine has continued to have

impact for 200 years because it makes a lot of sense.

Truth be told, America

did not have the muscle to completely enforce the doctrine at the

time. However, in

Great Britain the U.S. had a "Big Brother" that did have the necessary

muscle. Known as "The Special Friendship", the political

destinies of England and America became nearly parallel throughout

the 19th Century. Every European power knew full well that to

mess with America meant to take on the British as well. Nobody

dared.

1898 was a turning

point. The

1898 Spanish-American

War fought down in Cuba resulted in a devastating defeat on the part

of Spain. This war not only marked the end of any Spanish presence in the

Caribbean Sea, it showed the world that America had become a

superpower in its own right. America began to emerge from the

shadow of its big brother and stand on its own two feet.

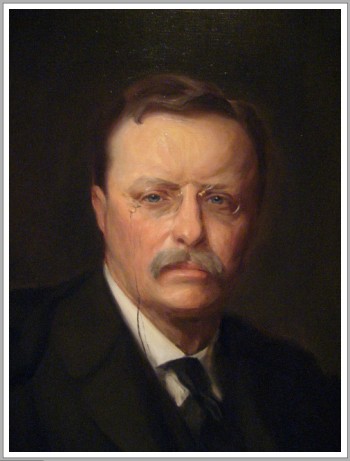

The man who deserves the

most credit for America's emergence at the forefront of the World's

stage was President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt's time in

office was remarkable in many ways. He would come to be regarded as

one of our country's greatest presidents.

Thanks to Teddy

Roosevelt's ensuing buildup of the Navy in 1901, the U.S. began to

treat the Caribbean Sea as its very own personal recreation pond.

Now that America had become a superpower, the Europeans got the

message: Not in my back yard.

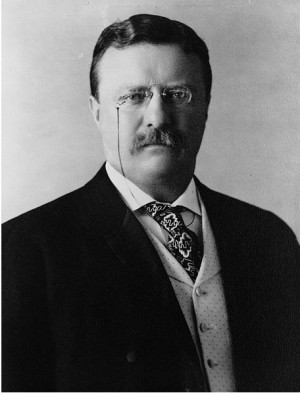

Theodore

Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt, who became president of the United States

in 1901. For someone nicknamed "The Teddy Bear", President Teddy Roosevelt

was undeniably aggressive. His famous motto was to "speak

softly, but carry a big stick".

Roosevelt got his start

fighting police corruption in New York City during 1880s. He

parlayed his good work there to a position in the Cabinet as

Secretary of the Navy. His stay was short-lived. When the 1898

Spanish-American War broke out, Roosevelt resigned his post to

form the Rough Riders. He headed down to Cuba to join the

fighting. He would win fame for his bravery down there.

Next Roosevelt won

a close election as governor of New York, but he didn't stay long in

that position. Instead he soon accepted the position of

Vice-President in the 1900 McKinley administration. He didn't

stay long in that position either. When McKinley was

assassinated in 1901, Roosevelt stepped in as President.

Thanks to all that fast-tracking, at 42 years, Roosevelt was our

youngest president to date. Roosevelt was the right man at the

right time. He

was a vigorous man eager to assert American

influence across the planet.

|

|

|

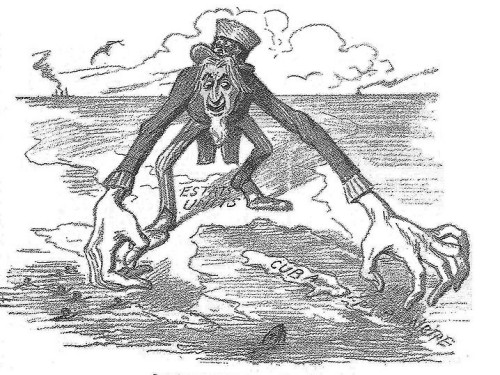

The Monroe Doctrine had

told Europe to mind its own business, but The Roosevelt Corollary

went one step further.

Thanks to its success at effectively

kicking Spain out of the Americas in the 1898 conflict, the United

States had begun to truly flex its muscles for the first time.

Now the country had just the right guy to flex those muscles a lot

more.

Roosevelt quickly made it clear that

America would intervene in any messy political situation involving

Latin America if it was in U.S. interests to do so.

Political events

involving Cuba, Panama and Venezuela led Roosevelt to assert the

right of the United States to intervene in Latin America affairs in cases of

“flagrant and chronic wrongdoing by a Latin American Nation”.

The U.S. made it clear it would be looking over the shoulder of all

its neighbors from now on. The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine was invoked to

justify military intervention in Latin America to stop the spread

of European influence.

|

|

The Roosevelt

Corollary was widely opposed by his critics. They

argued that the Monroe Doctrine was originally meant to stop

European influence in the Americas, not to interfere with

the actions of neighboring nations.

Roosevelt could have cared less. His Corollary asserted the

obvious fact that since the U.S. had domination in the Americas, it

would not passively sit around during conflicts. Henceforth, the

United States would play the role of "hemispheric policeman".

If anyone doubted

Roosevelt was serious about his willingness to use the military to

intervene in Latin American politics, the coming situation involving

Panama quickly dispelled those thoughts.

|

|

|

|

|

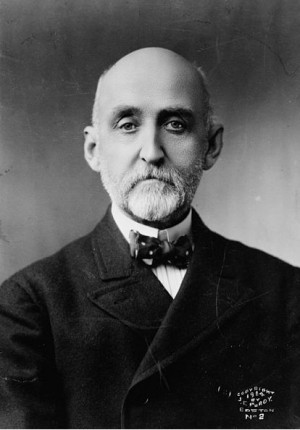

Alfred

Thayer Mahan

Alfred Thayer Mahan was

a Naval officer who won fame as a Naval historian and as the leading

Naval strategist of his day. Mahan was called "the most

important American strategist of the nineteenth century."

His concept of "sea

power" was based on the idea that countries with greater naval power

will have greater worldwide impact. His ideas still permeate the

U.S. Navy Doctrine.

Mahan was appointed

President of the Naval War College in 1886. One year later

Mahan first met Theodore Roosevelt, who came to the college as a visiting lecturer.

The two men became fast friends. Three years later, Mahan

published his famous naval doctrine, "The Influence of Sea Power

upon History, 1660-1783". Theodore Roosevelt read the newly

published book in a single weekend.

Roosevelt never forgot

what he learned from the book. Roosevelt completely agreed the

United States would need to protect its sea lanes around

the world to become a great nation.

Thanks to the ideas of

Mahan, Roosevelt

became obsessed with naval power. Sea

power was necessary to facilitate trade and peaceful commerce,

so the country with the greatest sea power would be able to

wield great influence on the world stage. Therefore, long

coastlines, good harbors, and power over places

like the Suez and the soon-to-be

Panama Canal was essential.

|

|

| |

|

|

Roosevelt and

the Spanish American War

By the turn of

the century, the Spanish had long outstayed their welcome in

the Caribbean. The people of Cuba were desperate for

independence.

All the U.S.

needed to intervene was an excuse. Following the

mysterious sinking of the USS Maine in the Havana harbor,

the U.S. had exactly the excuse it needed. In fact,

the sinking of the Maine was so mysterious that legend

suggests the USA blew the ship up itself. But that is

another story.

To the cries of

"Remember the Maine!", Spain and the U.S. began a major

conflict in 1898 which took place down in Cuba.

The USS Oregon,

a battleship stationed in San Francisco, was dispatched to

take the Maine's place, but the voyage around Cape Horn took

67 days.

Although the USS

Oregon finally arrived just in time to join in the Battle of

Santiago Bay, the voyage would have taken just three weeks

via Panama.

|

This delay had been very

upsetting to the US Navy. What would happen if the U.S. was

involved in another major war that required the rapid use of naval

power trapped in the wrong ocean? The frustration gave rise to

the idea that a U.S.-controlled canal across Central America was of

vital strategic interest to the U.S.

Interestingly, this

theory was quite prescient.

The anticipated military significance of the canal was

finally proven in

World War II. After Pearl Harbor,

the Panama Canal proved crucial when the United States used the canal to help revitalize

their devastated Pacific Fleet. The immense

strategic value of the Panama Canal allowed the U.S. to "reload" in

the Pacific a lot faster than the Japanese had expected.

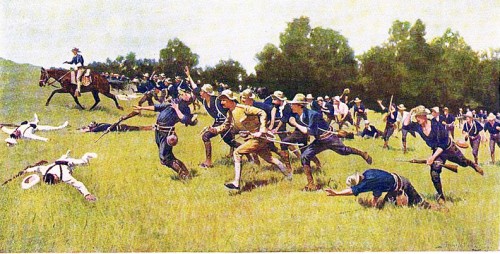

Back in 1898, Teddy

Roosevelt had played a major role in the

Spanish-American War.

There he gained fame for his charge up San Juan Hill along with his

Rough Riders.

Unwilling to sit back

and command from the rear, Roosevelt was right in thick of the

fight. He actually led the charge himself despite facing heavy

gunfire that cost many lives that day. Roosevelt was later

given the Medal of Honor for his courage and leadership.

Although he was an Army

guy during the

fighting in Cuba, Roosevelt had found time to pay close attention to

the frustrations of the Navy

following the

destruction of the battleship USS Maine.

|

|

Interest in

Panama Grows

A

firm believer in Captain Mahan's theory of sea power,

the moment Roosevelt became President in

1901, he immediately took

steps to revitalize the U.S. Navy.

During

the Spanish-American War of 1898, the United States had gained

control not only of Cuba, but the Philippines and the island of Guam.

By coincidence, the annexation of Hawaii had just taken place in

1898 as well. Mahan's ideas of national security had strongly

recommended bringing Hawaii

into the fold. Now that America's empire stretched from the Caribbean across

the Pacific, the old idea of a canal connecting

the two oceans took on new urgency. Recalling

the lessons learned down in Cuba, Panama was foremost in Roosevelt's

thoughts.

Mahan had predicted that "the

Canal will

become a strategic center of the most vital importance."

Teddy agreed. "The canal," Roosevelt said,

"was by far the most important action I took in foreign affairs

during the time I was President. When nobody could or would exercise

efficient authority, I exercised it myself.

That canal had to be built hell or high water."

"No single great material work which

remains to be undertaken on this continent, "Roosevelt said, "is as

of such consequence to the American people."

However, before any work

could begin on the Panama Canal, Roosevelt would first have to pick

up the pieces from the French.

|

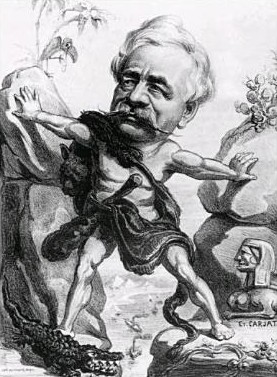

Ferdinand de

LessepsFerdinand Marie de Lesseps was

an entrepreneur extraordinaire. A citizen of France,

de Lesseps was the man responsible for the construction of the

Suez Canal which was completed in 1869.

De

Lesseps was not an engineer or an architect,

but he was a dreamer and schemer of the first magnitude.

According to his admirers, de Lesseps had nerve, imagination,

dynamic energy, persistence,

plus a talent for propaganda

and maybe even a capacity for deception.

With his outgoing social manner and his

dream firmly in place, the moment de Lesseps

completed the Suez

Canal project, he began looking for his next great

accomplishment.

De Lesseps had fascinating

ideas that kept the public

enthralled. He envisioned railways from Paris to Moscow to Peking.

He talked about creating an

inland sea in the Sahara Desert by breaking through a ridge on Tunisia's

Gulf of Gabes and flooding a depression the size of Spain.

De Lesseps was one of

the few men on earth actually capable of getting these gigantic undertakings

off the ground.

He was able to

obtain and handle money like no other man in his

time. Due to his immense charm and his Suez

success, people in high places were willing to hear him out on his

Panama concept. He was now one of the most famous men in the

world.

|

|

|

With completion

of the Suez Canal, de Lesseps changed the

world and captured its imagination.

By coincidence, the completion of the

Suez Canal concurred with another famous event - the completion of

the first US transcontinental railroad. These two events made

the entire world a much smaller place. Another famous dreamer

in his own right - Jules Verne - took note and wrote his famous

"Around the World in 80 Days". This saga described a journey that used both the Suez

Canal and the U.S.

railroad developments in the plot. It was a great book that

captured the spirit of these exciting

times.

In

1875 de Lesseps decided to take on the

project of building a canal between the Pacific and

the Atlantic

in Central America. He was definitely the

right man for this massive project.

De Lesseps was

viewed around the world as an all-conquering hero.

His work on the Suez Canal

gave him the international acclaim necessary to garner financial

support for this new undertaking. Everyone agreed if anyone

could do it, that would be Ferdinand de Lesseps.

In May of 1879, de Lesseps hosted a meeting

with delegations of 22 countries around the world.

In this meeting, there was much discussion

over the

tactics on how to build the canal. This delegation

brought suggestions to the floor on the type and location.

The first issue

was a

debate over whether the canal should be built in Panama or

Nicaragua.

|

When Panama was chosen, the next argument

was whether it should be a sea level canal or a

lake and lock canal. De

Lesseps declared that it would have to be a sea level canal.

A lot of people quietly

believed de Lesseps was making a big mistake. The problem of a sea level canal was seen

right away in terms of the landscape that the canal was to be built

on.

The Chagres River was

seen as the single biggest obstacle to the success of the project.

Any canal at

Panama - a lock canal or

a sea-level canal -

would have to cross the river at least once.

Surely the canal would

have to pass the bend of the Chagres River at Gamboa. The

river was 42 feet above sea level at this point. If a

sea-level canal were cut through, the river would

fall to the canal

from 42 feet above.

It would definitely make for a spectacular waterfall, that's

for sure.

In the rainy season the river could be instantly transformed

into a torrent, rising ten feet in an hour. The

cost of controlling so monstrous a force -

if it could be done at all -

was beyond reckoning.

|

|

De Lesseps was

undeterred. One of his greatest skills during the building of

the Suez Canal had been his ability to ignore the critics and

naysayers. The French had the greatest engineers in the world.

De Lesseps was certain that when the time came, his engineers would figure out a way to bring this

tropical river into line with his project. Bristling with

supreme confidence, De Lesseps

immediately started fundraising and propagandizing the campaign.

Investment money came pouring in. The

project was a go.

Construction began in

Panama

in

1880. Almost from the start, everyone could see this was infinitely more challenging than the Suez in every aspect except

for the distance. Furthermore, any

lesson that the Suez had

provided was useless. The

French had assumed building one great canal would make the second

one easier, but they were wrong.

This wasn't sand they were digging through, it was

rock!

Just to get started, the

French had to go into a thickly matted jungle that had poisonous

reptiles, jaguars and pumas, as well as tons of insects.

In the summer of 1881,

the French discovered to their dismay they had an enormous

unanticipated problem to deal with - yellow fever and malaria.

As the number of laborers increased,

so did the death rate. By the end of 1883, 1,300 laborers had died

throughout the year. Fear and anger surged

through the ranks. This damn Canal was a death trap!!

|

|

|

The rate of sickness seemed to only get worse.

At the peak of the problem laborers were

dying 200 per month. The worst year for the French

regime in Panama was 1885, where up to forty people per day died at

times.

All told, the French lost an

astounding 22,000 men in the process. There have been many

well-known wars where the casualty rate came nowhere close to that kind of

mayhem. Getting sick was tantamount to a death sentence. Half

the people who got sick died.

Be it lowly diggers or

the important college-educated engineers, no one was

safe. Vast

numbers of employees ranging from laborers to top directors of the

French company were sickened and killed. The specter of death

hung over the project. What was killing these people?

At the time, no one had any idea what was causing the

problem or how to combat it. The amount of fear and

dread was unbelievable. Everyone felt defenseless.

Would today be the day?

The French got away with

this death rate because they kept it a secret. They recruited

most of their labor force from French-speaking islands in the

Eastern Caribbean. They made sure news of this problem did not

reach those islands. They make it very difficult for people to

leave.

No matter how hard French officials tried to suppress the news, something

this serious could not stay hidden forever. Once the general

public discovered the truth, no one else would risk their life and

sign up to work. The French had no choice but to quit.

|

The death toll was not the only number

increasing at a rapid rate. So too was the financial cost.

De Lesseps’ efforts to raise the

proper money were without comparison in his time. He was truly

talented at raising money for his projects and inspired many of his

countrymen. Unfortunately, the conditions kept getting more arduous

in Panama and de Lesseps had to keep justifying to the French

government to give him more money. While his efforts were valiant,

in February

1889, the shareholders of the original company assigned a liquidator

and the French effort was brought to an end.

De Lesseps could only whisper, “It is

impossible! It is shameful!”

In the end, de Lesseps'

constant optimism proved his ultimate undoing. As he had done

at the Suez Canal, he refused to listen to people who disagreed with

him. For example, the construction of the Old Panama Railroad 20

years earlier had cost upwards of 6,000 lives due to disease.

De Lesseps knew about this tragedy, but paid no attention to it. That sobering fact

should have dampened de Lesseps' enthusiasm, but he just ignored it.

Just because all those men died in 1860, why should they die in

1880?

As yet another example of his insouciance, de Lesseps only Panama once

before starting the project. His visit had taken place

during the relatively mild dry season. While he was there, he saw nothing that

bothered him very much. People who knew Panama intimately

tried to warn him, but de Lesseps dismissed them. He simply

wasn't the kind of person who wanted to hear negativity.

Unfortunately, his

over-confidence led him into a trap. Once construction

began, his crew

discovered the real Panama - mile upon mile of impassable jungle,

day upon day of torrential rain, insects, snakes, swamps, hellish

heat, smallpox, malaria, and yellow fever.

Perhaps his greatest

mistake was ignoring the Chagres River. The Chagres snaked

across the proposed canal route a total of fourteen times. Ignoring

the warnings of engineers who deemed the task impossible, de Lesseps

had decided he would dam and divert the river, which he had only seen

first-hand at

low ebb during the dry season. Now suddenly in the rainy season, the engineers paled

as the Chagres rose to a monstrous, churning torrent that swept away

anything that stood in its way. This angry, swollen river was distinctly inhospitable to

taming.

For ten long years, nothing went right.

De Lesseps

would die 5 years after the project collapsed. The

countless deaths, the unending harassment of his creditors, the

jeering criticism of his enemies and the knowledge that he had

failed in the greatest effort of his life made his final days sheer

torture. Some people suggested he died because he wanted to.

So much for the man who

pursued his dreams. He was a tragic figure, a broken man. Like the story of Icarus, the birdman who

flew too close to sun, de Lesseps' fate is a grim reminder that

while some visionaries succeed, many others die when they shoot for

the moon.

In the end, de Lesseps was caricatured as the man

who started as a canal digger, but became a grave digger instead.

How is that for an epitaph?

|

|

Gunboat Diplomacy

Thanks to the French

collapse, the United States saw

a golden opportunity. However, the

Americans were not naive. They could see there were enormous hurdles to be

crossed.

After studying all angles of the

issue, Roosevelt was persuaded by Mahan's theory of naval power that

the advantages were worth the risks.

The moment Roosevelt took office

in 1901, he ordered his staff to begin negotiations with the French

for the rights to the Panama Canal project.

The

French were more than happy to comply. It would be nice to

recoup some of their immense financial losses. Roosevelt agreed

to pay $40 million for the rights... and was

immediately criticized by the press who suggested he could have

gotten a better deal.

The United States

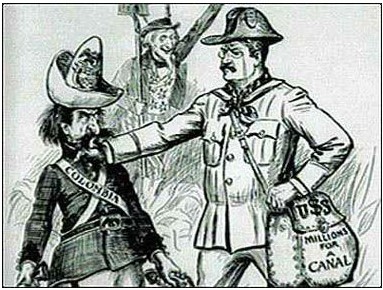

government voted to begin work on the Panama Canal in 1903.

However, since Panama was a territory of Colombia, first the U.S.

needed to obtain the same permission from the Colombians that had

previously been given to the French.

|

The government of

Colombia noticed how much money the French had received and decided

to play hard to get. Colombia decided to vote against the project.

Roosevelt was incensed. This was

basically blackmail.

Roosevelt had offered $10 million

- quite a sum of money in that day - for a fifty-mile strip of unused,

uninhabited jungle across the isthmus only to

see Colombia refuse.

The Colombian government wanted

significantly more money.

Roosevelt had no intention of paying

any ransom money. He realized he had a better option, but it would

force

him to engage in a bit of political skullduggery to

get the project going again.

"We were dealing with a government of irresponsible

bandits," Roosevelt stormed. "I was prepared to

occupy the Isthmus anyhow and proceed to dig the

canal whether Colombia liked it or not.

But I deemed it likely that there would be a

revolution in Panama soon."

Teddy already knew there

was a powerful independence movement taking place inside Panama.

The people who actually lived in Panama knew the canal was clearly

in their best interests. They deeply resented the interference

of Colombia. And why should Colombia get all that money?

The people in Panama would never see a cent of it.

|

Just as important, the

chief engineer of the French company

holding the rights desperately wanted the sale to go through. Roosevelt smiled. Why not help the local

people a little? So the United States sent word they

would support a

revolt in Panama. Encouraged, the French engineer

organized a

local revolt.

Roosevelt immediately sent the battleship

Nashville and a detachment of marines to Panama to support

the new government. The US Navy just happened to show up

in a bay outside of Colombia a

day before the revolt.

The revolt started and

ended in two days. Colombian troops

were immediately dispatched to quell the opposition, but found their sea lanes

blocked by American warships. The dense jungle

separating Colombia and Panama made a land approach

impossible, so there was no chance of reinforcement by land.

|

And what about the

Colombian soldiers stationed in Panama? Colombian soldiers in

Colón were bribed $50 each to lay down their arms. Faced with

the choice of dying or getting significant money to ignore a fight

over a place they could care less about, their desire to

resist quickly faded. The Revolution took place without any loss of

life. Just like that, the new Republic of Panama was

born.

Not surprisingly, the

new government was much more cooperative.

The rebels gladly accepted Roosevelt's

$10 million offer and gave the United States complete

control of a ten-mile wide canal zone. A lease was quickly signed

and construction followed shortly

after. Using the abandoned French machinery,

the United States

began working on a lock-based canal

a year later in 1904.

|

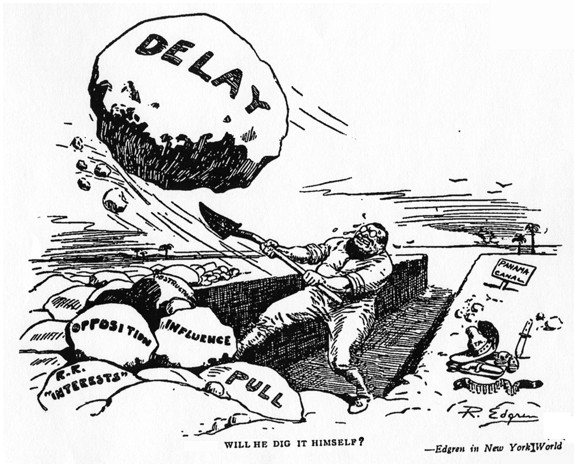

Political Opposition at Home

Given the

crushing failure of the French, the success of the American effort

was in no way guaranteed. There was an alarming amount

of disagreement on whether this project made any sense.

Roosevelt faced a

lot of heat back at home.

Looking back in

time from our 100-year perspective, it isn't easy for us to

understand that there was tremendous political opposition to the

building of "The Big Ditch" as it was called. However,

we have the advantage of history.

From the point

of view of Roosevelt's critics, he was taking an enormous

risk. Thanks to the French problems, failure seemed a

real possibility.

Back when the

feasibility of the Canal project was being debated, the

enormous cost and the awareness of all the problems the

French had faced caused many important people to dismiss the

project as a preposterous waste of money and time.

|

|

The critics were mad

about all sorts of things. First they were mad that the U.S.

had given the French too much money for rusting equipment.

Next, the political

opposition of the Colombian government played right into their

hands. Roosevelt's political enemies deeply criticized

Roosevelt's use of bullying tactics to solve the problem.

The major risk of life

due to the mysterious disease was yet another added negative.

As news of the enormity of the French loss of life slowly became

more widely known, there was a lot of fear involved.

To Roosevelt's opponents

in

1904, they assumed Roosevelt was biting off more than he

could chew. If a great man like de Lesseps with a

proven track record couldn't do it, what made Roosevelt

think he could? Everyone knew Roosevelt was brave, but

charging up San Juan Hill with the Rough Riders wouldn't

help in this case unless those Riders had shovels.

Too bad

Roosevelt was merely a President. Unlike the Pharaoh

who could simply order men to build the Pyramids or face death, Roosevelt had to answer to

all these people.

Fortunately, President Roosevelt refused to cave in.

He gamely took on all comers and argued them down.

Roosevelt later

reminisced, "There was much accusation about my having acted in an

'unconstitutional' manner. I took the

isthmus, started the canal, and then let the

Congress debate me. They can

debate all they want. While the debate

goes on, the canal does too. They are welcome to debate

me as long as they wish, provided that we can go on with the

canal."

His

political critics weren't his only problem. Although Roosevelt

maintained a strong public face on the Canal project, secretly he

was starting to have his doubts as well. Thoughts of the French

failure weighed heavily on Roosevelt.

Roosevelt realized how fragile his margin of support was.

The project had gotten off to a terrible start.

Roosevelt

knew that the Americans' first year in Panama

had closely mirrored the French disaster.

Same problems, same lack of solutions. Now people were

starting to die down there. The clock was ticking.

Roosevelt grimly wondered if he was facing failure on a giant

magnitude.

The first chief

engineer on the job, John Wallace,

was ineffective. He neglected to organize the effort or to develop an action plan. The

food was putrid, the living conditions abysmal. Nor

did Roosevelt's opponents make it easy for Wallace to succeed. Political

red tape created by Roosevelt's enemies put a stranglehold on appropriations.

The mountains of red tape

drove Wallace out of his mind with frustration.

Then the disease

began.

Uh oh. The Americans weren't trapped like the poor

miserable Caribbean who had been stuck there. 3 out of 4 Americans booked passage home

at the first chance. During 1904 the

Americans had poured $128,000,000 into the swamps of Panama

and had practically nothing to show for it. Roosevelt was

discouraged. Things didn't

look too good down there.

As problems mounted in

Panama, Roosevelt knew he was

taking a serious gamble. Only the extreme

distance kept this negative news from breaking in the papers.

Roosevelt worried that he was running out of time. One serious disaster

and

the voices of dissent would become nearly unbearable. Considering

all the opposition he faced, politics was obviously not for the

faint of heart.

Roosevelt

didn't trust his engineer Wallace.

He recalled the man to the White House and demanded his resignation. Wallace was thrilled to give it to

him. Wallace had some parting words. "No one can save this project."

Chilling words indeed.

|

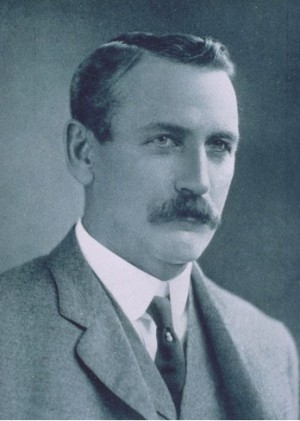

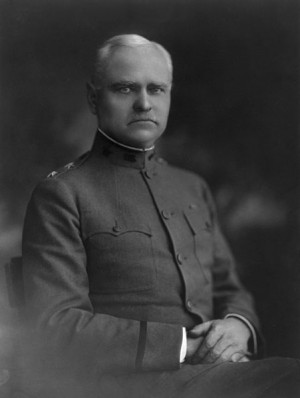

John

Frank

Stevens

Well aware of the problems

Wallace had run into, a sense of déjà vu haunted Roosevelt. He knew

the French engineers were in all probability just as good as the

American engineers. How could the Americans succeed where

competent men from another country had failed so miserably?

And what about this infernal sea level versus lock system debate?

Roosevelt was down to his last chance.

The man who saved the day was John Frank Stevens, Chief Engineer from

1905 to 1907. Stevens was the man who convinced

Roosevelt the

idea to build the "locks" was the right move.

The decision of

which canal system to use was highly controversial. No one

could be sure which system would work because something on

this scale had never been attempted before.

There was no consensus; the experts were split

right down the middle. Some said the sea level approach was

best and others said the locks system was best.

The first American to

ever investigate the idea in depth was

Commander Thomas Selfridge.

In 1870 he took two expeditions through

Panama's Darien Gap.

Selfridge was certain on how the

canal should be built, saying it must be "through-cut" at sea level.

Ferdinand de Lesseps was convinced sea level was the way to go.

John Wallace, the first American Chief Engineer on the project, had

also been convinced that sea level was the way to go.

Furthermore, the U.S. commission assigned to study the question

pointed out the sea level approach had worked in the Suez. They

all agreed with Wallace. Build the canal at sea level!!

|

|

|

Betting

the Farm on a Radical Idea

It takes a lot

of guts to contradict intelligent, educated men who are

convinced they know what's right. Was John Frank

Stevens qualified to make a decision of this magnitude?

What was his background? What papers had he written?

What exactly was his training?

Stevens had no

canal training at all. Zero. Nada. He wasn't an

architect. He wasn't an engineer. Heck, he

wasn't even a college graduate. Even more ridiculous, he had

never been near water in his life, much less dug a canal.

On paper, John

Frank Stevens could not have been less qualified.

Stevens was a

railroad man... a very good one at that. That skill

would come in handy when moving the dirt around, which is

what got him the interview with Roosevelt in the first

place.

But what did

building railroads have in common with building canals?

Probably not much, but it didn't matter. Stevens was a

practical man, self-taught. He had twenty years of

experience at building railroads and managing large

projects. Stevens figured whatever he didn't know, he

could learn.

Stevens

understood the main decision facing the engineers was

whether to build a sea level or high-level, lake-and-lock

canal. The stakes were enormous. No one could

afford to get it wrong. There was no room for error.

The French had chosen Panama

over Nicaragua primarily because they believed it could

support a sea-level canal, the system they were more

comfortable with.

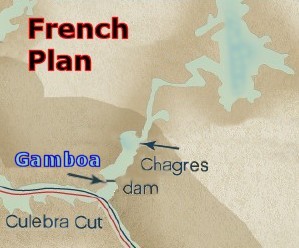

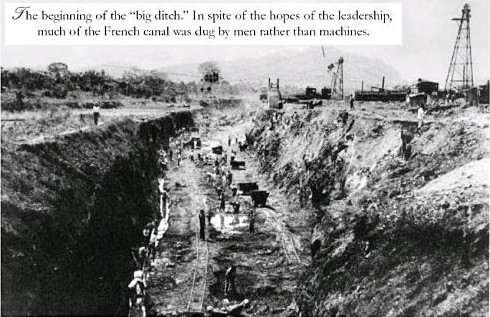

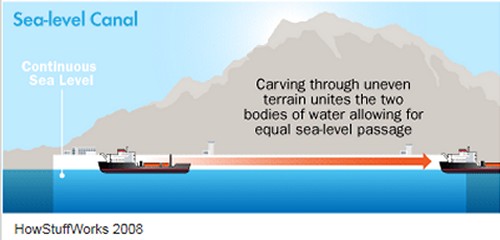

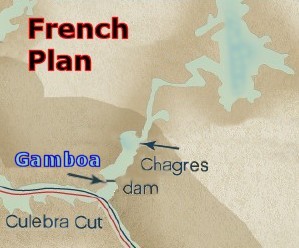

As the picture

from "How

Stuff Works" shows, the French were ready to carve

through whatever was in their way for 50 miles.

|

|

|

The French were

unwilling to take a high-stakes gamble on locks. No one

could be sure the "lock technology" of the day was advanced

enough to work with huge ships. This wasn't exactly

the Erie Canal they were proposing to build.

Yes, the "lake

and lock" approach was perfect for the small ships that

operated on rivers and lakes. But these were giant, heavy ocean

liners they were dealing with, not some wooden tub on a

lazy river. Would locks work with the enormous freighter

ships of the ocean? There was no solid evidence they would.

Using locks with modern ships was unproven technology.

In some ways,

the French were victims of their own success. The

French did not like taking chances. Thanks

to their world-renowned accomplishment at the Suez Canal, the French

could not seem to let go of the sea level approach.

The sea level canal might involve a lot of work, but it

seemed like a sure thing.

Just dig

dig dig till the whole thing was done. Let the Pacific

waters kiss the Atlantic waters in perfect harmony in the

middle of the canal at sea level. Voilà!

The French Connection!

|

|

|

Rick's Note: I drew these two pictures

based on my understanding of what I read. What I am about to

say is a bit harsh, so I wish it to be known that these are

my words alone. I wasn't there, so let's be clear I am

drawing conclusions based solely on what I have read and

nothing else. As they say, take my words with a grain

of salt.

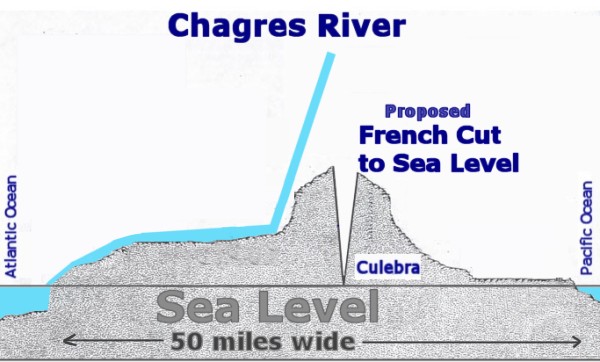

CULEBRA CUT

The French plan was

to build at sea level. The eventual U.S. plan was far

more complicated. The top of the Continental Divide at

Culebra was 336 feet high. Unless I am missing

something, that meant the French planned to cut through 336

feet of solid rock down to sea level. The American

plan would call for a cut of 120 feet. Even with the

head start given the Americans at Culebra by the French, it

still took the U.S. about 8 years to finish their 120 foot

cut. How long would 336 feet have taken?

What were the French thinking?

50 MILES OF SOLID ROCK

The isthmus was 50 miles wide. Unless I am missing

something, that meant the French intended to excavate the

entire 30 mile bed of the Chagres River plus 10 miles at the

Culebra Cut (plus 5 more miles at both ends).

First of all,

how were they going to get the Chagres River to behave while

they dredged through its channel all the way to the

Atlantic? Or were they going to dig another massive

river bed right next to it?

The French had

dug through 100 miles at Suez, but a third of the distance

was lake and the rest was mostly

sand. Here at Panama, the French dug

and dug and dug for ten long years. During this time,

they partially

cleared about 11 miles of the eventual 50. At the rate

they were going, their plan

would take at least another 20 years. 50 miles of

digging through solid rock?

What were the

French thinking?

|

|

CHAGRES RIVER Furthermore, the

French still didn't have an answer for the troublesome

Chagres River. Once

the French engineers finally saw the Chagres up close, they

did a double-take. This river was a tropical beast when it

rained. At 42 feet height above sea level, it threatened to

send massive amounts of water bearing down at a right angle

exactly at Gamboa, the spot where the "sea level"

canal would meet the Chagres.

How exactly were they supposed to

bring a 42 foot high monster down to sea level? The

ever-confident de Lesseps expected his engineers would build

a dam. Unfortunately, the spot de Lesseps had chosen

for his dam was virtually impossible since the river was so

wide at that point and there was no convenient canyon nearby

to help build the dam. The sea-level plan

seemed no match for the mighty Chagres River.

What were the

French thinking?

|

Given that it seems

so obvious to a modern reader what the correct solution was,

it is hard to accept that the French were so determined to

use their sea level concept. The only possible

explanation that makes any sense to me is that the concept

of using "locks" was far too radical for that time. To

be that stubborn, the French must have thought using locks

to build the canal made about as much as sense as telling an

ancient that the world was round, not flat.

Humans like to

pride themselves in their curiosity, but we all have blind

spots about things that make us feel foolish later down the

line when the truth is revealed. That is why education

is so important. One of the first things people learn

in education is the more we know, the more aware we become

of what we don't know. In the case of the French, this

blind spot about the correct plan to use led to one of the

most colossal engineering failures in the history of man.

|

Baron Adolphe Godin de Lépinay

In 1879

promoter extraordinaire Ferdinand de Lesseps convened a conference in Paris.

The conference had the stated purpose of inviting engineers

from around the world to make proposals on how and where to

build the canal connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific.

However, later reports suggested that the secret purpose of the

conference was simply to create an aura of legitimacy to

help raise money. By providing the appearance of

impartial international scientific approval, de Lesseps

would be able to claim that no stone had been left unturned

in approaching this project this the right way.

Unbeknownst to

many, De Lessups already had his mind made up before the

conference ever began. He favored a sea level canal plan

using the shortest distance possible in Panama. He was

drawn to his preferred location by the existence of the Panama

Railway. Not only was the jungle already clear along

this route, the train would help immeasurably in transporting

equipment, men, and earth.

Fourteen

proposals for sea level canals were presented before the

Congress. To de Lessep's surprise, the American

delegation had an excellent plan to build a canal in

Nicaragua. The well organized and persuasive presentation by

the Americans very nearly upset de Lesseps' carefully

orchestrated plans. A subcommittee reduced the route

choices to two -- Nicaragua and Panama.

De Lesseps was

forced to quietly ask various members of the large French contingent at the Paris

meeting to help vote down the Nicaragua proposal.

Then, to his

surprise, de Lesseps had another curve to deal with.

Even more surprising, the note of dissent

came from someone within his own faction. A man had the

nerve to suggest a lake and lock canal system. De Lesseps

nearly had a heart attack. It wasn't just him either.

The entire conference was aghast.

What kind of insane idea was this?

Baron Adolphe

Godin de Lépinay was a brilliant and highly experienced

engineer. He was the only person among the French

delegation who actually had any construction experience in

the tropics. In 1862, de Lépinay had overseen

construction in Mexico of a railroad between Cordoba and

Veracruz. This was one man who actually knew what he

was talking about. At the congress, de Lépinay made a

forceful presentation in favor of a lock canal.

De Lépinay

started his presentation by saying he agreed with the Panama

route over the Nicaragua route. De Lépinay then added

he had conducted a careful first-hand study of the terrain.

In his opinion, the presence of the Chagres River doomed any sea level plan

to failure. Then he dropped his bombshell - why not

raise the river? Build a dam upstream, create a lake,

and raise the river.

The audience

gasped. This was utter stupidity! Men were so

upset that they interrupted his

presentation with strong protests. De Lépinay was

completely taken aback by the sharpness of the men's voices.

Not surprisingly, their behavior

rubbed de Lépinay the wrong way. De Lépinay was known

for his intelligence, but he also possessed a condescending

attitude towards those with who did not agree with him.

De Lépinay scolded the men for their rudeness and

demanded to be heard completely. Then he made the

mistake of rebuking the protesters. "You men need to sit

down and be quiet. You have no idea what you are even

talking about."

That only served

to anger the crowd more. De Lesseps saw

an opening. He spoke up and dismissed this unusual

idea as preposterous. Upon hearing this, de Lépinay was indignant.

He reminded de Lesseps he had spent several months inspecting the location and

preparing his arguments. He resented being treated as a dilettante.

De Lesseps

knew he had the crowd on his side, so he just laughed. De Lépinay

was flabbergasted as being dismissed so easily. He

couldn't believe de Lesseps was so flippant. He

protested vigorously for de Lesseps to allow him to be heard

out one more time, but it was no use. De Lessep's mind had already been made up.

They

would do it his way. Shoved aside by de Lesseps, de Lépinay's design received no serious attention.

This was quite a

confrontation. Here we had two powerful personalities

who shared a similar fatal flaw - arrogance. For

all his brilliance, Baron de Lépinay was not someone who

suffered fools easily. His sense of superiority eroded

his patience. Offended by the insulting tone

of men who should have had better manners and more open

minds, he refused to wait until the furor died

down. Instead, he was far too angry to

defend his controversial ideas in a calm manner. He

brusquely stomped off.

It probably

seems preposterous to a modern reader that de Lépinay's plan

was given such short shrift. However, the concept of

using locks to accomplish this goal was apparently way too

far ahead of its time to the engineers of 1879. De Lépinay

meet the same kind of resistance to his idea that Galileo

met for suggesting the sun was the center of the our solar

system. It was just too radical for the time and

unfortunately de Lépinay did not possess the temperament to

hang in there and defend his ideas. That's too bad.

If

someone been willing to listen, it is quite likely that the

French would have ultimately succeeded in their effort.

De Lesseps'

arrogance would cost him even more. His mistake was assuming he knew more than he did. He

acted just like a Hollywood mogul who thinks that fronting

the money for a film somehow makes him qualified to

contradict the director's vision.

De Lesseps was a

trained diplomat, not an engineer. This was an

important fact that perhaps he should have remembered more

often during canal design decisions.

De Lesseps was

excellent at handling the important work of promoting and

raising money for the project from private subscription. Not

having the least scientific or technical bent, de Lesseps

relied upon a rather naive faith in the serendipitous nature

of emerging technology. He figured it was safe to

start an enormous project without having all the questions

answered ahead of time because surely they would find a

solution when the time came.

Thus he worried

little about the problems facing this gigantic undertaking.

De Lesseps felt sure that the right people with the right ideas and

the right machines would somehow miraculously appear at the

right time and take care of any unforeseen problems. Sure enough, his

boundless confidence and enthusiasm for the project and his

consummate faith in the miracles of technology attracted

stockholders, but in the end de Lesseps surely realized that

he should have listened to the warnings before it was too

late.

It is impossible

to accomplish great things without confidence. But how

does someone know they are over-confident? How does

someone know when they are listening to the wrong person?

How does someone know when they have a blind spot? How

does someone know when they are in over their head?

Great

accomplishments carry great risk. It is easy for us to

look back at de Lesseps with the hindsight of 100 years and

dismiss him as a close-minded fool. Personally, I think we

should cut the guy some slack. Sea level worked at

Suez; why wouldn't it work at Panama?

Learning Things the Hard Way

In the final

days of the project, it became increasingly obvious to the

French that the

sea level plan would not work after all. Gustave Eiffel,

builder of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, was approached about

building canal locks. However it was too late in the

game. It was over before the changes could be made.

After the French

effort collapsed in 1890, the French engineers quietly got together

and compared notes. They discussed what they had learned. Baron de Lépinay participated in those

discussions. He felt vindicated that he had been

right the entire time.

The death of

Ferdinand de Lesseps in 1894 made it easier for the

engineers to

finally

whisper a blasphemy in public - maybe they had gotten it wrong the

first time. That had to be a humbling experience.

In 1897, de Lépinay

made his proposal again. If it was so difficult to

lower a 42-foot high river down to sea level, why not raise

the waters up to 42 feet... or, better yet, even higher!?

Why not 85 feet?

De Lépinay

agreed with de Lesseps that the Chagres needed to be dammed.

However his idea was to put the dam much further down the

river at the end of the low-lying Chagres Valley.

This would

create an artificial lake that would be connected to the cut through the

Continental Divide. This way no one would have to dam

the Chagres at the Gamboa T-connection, but rather simply

let the waters merge at whatever level 42 feet or higher.

|

|

Although early U.S. developers

rejected this plan (including John Wallace, the first U.S.

Panama engineer), when John Frank Stevens studied it, he liked it.

De Lépinay had

pointed out that locks are the best way to carry a waterway

over uneven terrain by raising and lowering the water level

in a series of step-like chambers. A canal without

locks simply carves through the terrain -- maintaining the

same water level from start to finish. The French plan

called for making the Culebra Cut all the way down to sea

level. That was solid rock! Although the French

eventually realized it's extremely difficult a cut through

solid rock, they abandoned the plan too late to

save the effort from failure. De Lepinay suggested it

wasn't too late to learn from this failure. His plan

only required the Culebra Cut to come down to 42 feet above

sea level. That would save countless years of

difficult digging.

John Franks Stevens

studied the problem and came to his own conclusion. He completely disagreed with the

original French sea-level approach to building

the Canal. Yes, on paper, it would undoubtedly work to dig down

and deepen the canal until the waters of the Pacific and the Caribbean

would become level, but it simply wasn't practical. Stevens sensed

the sea level plan would only be accomplished at a cost no

one would be willing to pay. It is probably impossible to

conceive exactly how much work this extra digging would be, but

hindsight estimates say

the incredible amount of excavation necessary would have

expanded the project two, maybe three, maybe even four times beyond the effort that was

ultimately expended by the U.S. laborers.

The main reason

everyone favored the sea level plan was the uncertainty

surrounding the lock proposal. The sea level system

had a well-proven track record. The Suez Canal was an

ongoing miracle that worked efficiently and required little

upkeep.

|

Stevens' system of "locks" would be complicated

and "new". The locks meant less work, but would they function

correctly? That was the big

question. No one wanted to take the risk. If the

lock system failed, they would be branded for life as the

idiot who suggested these contraptions.

Stevens discussed it with several of

America's leading "lock engineers". They all assured

him the locks would work. Stevens made up his mind...

he would only take the job if he could design a locks and

lake system.

Stevens

carefully explained to Theodore Roosevelt the feasibility

of an above sea-level canal built with dams and locks.

Stevens explained how he would dam the Chagres and create an

artificial lake.

Roosevelt was

not only persuaded, he was impressed. Stevens was

quietly brilliant. He gave Stevens permission to

do it his way. Stevens was hired just three days after

Wallace had been fired.

|

When word of

Wallace's dismissal and the

change of plan reached the press, not

surprisingly, Stevens' decision to reverse Wallace came up against a tremendous amount of opposition.

"It'll never work!" "Stick to the tried and true!"

The critics sounded just like the naysayers from Ayn Rand's

novel "The Fountainhead", a book which celebrated individual

vision over an establishment preoccupied with worship of

tradition. 'You should build it the usual way because

the usual way is usually right!'

You have to

admire the man. Against all the predictions of doom

and disaster from the experts, Stevens stuck to his guns.

They were going to do it his way. Of course, de

Lesseps had said the same thing. Stevens was well

aware a lot was riding on him being right.

Stevens to the Rescue

Amidst all the

controversy, John Frank

Stevens arrived in Panama in 1905 as the second Chief

Engineer. Stevens was immediately taken aback by the

terrible morale and living conditions. On the spot, Stevens

decided the project needed to take care of the people first

and foremost. He would get to the

engineering effort second.

With confidence and morale

desperately low among the workers, one of Stevens' first

actions was to introduce a food car. Then he created a

social hall for

entertainment. Next he began improvements in housing.

The kind of hard work that

needed done, Steven reasoned, could only be done by a

well-housed, well-fed labor force that was free of disease. Stevens

began work not by not digging, but by cleaning. The

digging could wait.

"The digging," Stevens said, "was the least thing of all."

That would become one of his favorite slogans.

Stevens wasted

no time tackling the disease problem. Stevens was the

first high-ranking official who ever took the threat of

the yellow fever-carrying mosquitoes seriously.

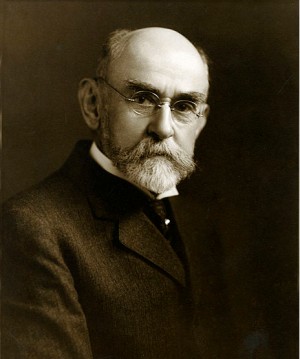

Stevens made a

point to sit down with Dr. Gorgas, chief medical official. Six years

earlier Dr. William Gorgas had

been part of the effort to eradicate yellow fever in Havana,

Cuba. His time there made him keenly aware of the dangers

the mosquitoes presented.

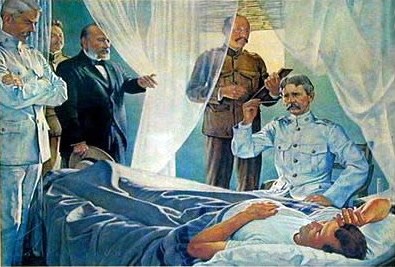

Gorgas had been an understudy of Dr. Walter Reed. Reed and Gorgas

were serving

with the U.S. Army in Cuba after the conclusion of the 1898

Spanish-American War.

When Americans

began getting sick in Cuba, Reed studied the work of Cuban

physician Carlos Finlay. Cuba had long suffered with the

same malaria and yellow fever problems as Panama.

|

|

In 1881 Dr. Finlay

had finally solved the mystery of how these diseases spread.

He identified the mosquito as the

disease spreading agent. During his stay in Cuba, Dr. Walter Reed was able to

confirm Finlay's investigative work and passed his findings

onto Dr. Gorgas.

That had been Cuba.

Now Gorgas was saddled with the task of protecting the American

workers in Panama.

Surprised that

someone was finally willing to listen to him, Gorgas quickly

recommended the workers be immunized against yellow fever.

Good move. The last case of yellow fever was reported

in November 1905, shortly after Stevens' arrival. It

was that simple, but no one had ever bothered to care

before. What Stevens lacked in formal education, he

made up for with decency and a natural ability to go straight to

the heart of problems.

Stevens also

asked Gorgas about the malaria problem. Gorgas explained to

Stevens that it was impossible to immunize against malaria.

However, that didn't mean they were helpless. Getting rid of the mosquitoes

was the trick. Gorgas recommended

several sanitation efforts. Stevens listened to Gorgas's suggestions and heeded his advice.

Stevens made sure to build proper housing with screens for canal

workers. He oversaw investment in extensive sanitation and

mosquito-abatement programs that minimized the spread of the deadly

mosquito-spread diseases. Workers

drained swamps, swept drainage ditches, paved the muddy roads and installed

plumbing. They sprayed pesticides by the ton.

The measures did not

make the malaria go away. After all, there was a vast jungle

just outside the living quarters. However, they did reduce the

mosquito threat dramatically.

Over the course of ten years, 5,600 men would die from malaria, but

that rate was nothing compared to the French experience. Even better,

more men recovered from malaria than died from it. Most of the

fear disappeared. Working together, Gorgas and Stevens had

accomplished a

miracle.

Stevens didn't

stop there. He continued to improve the quality of life

for the men. Entire towns rose from the jungle,

complete with clean housing, schools, churches, commissaries,

and social halls.

With sanitation efforts

complete, adequate housing built, and his workers' welfare on the mend, Stevens

was ready for the next step.

Stevens was a railroad

guy, so his next move was to rebuild

the Panama Railway completely to his liking. For one thing,

parts of the old railway would have to be submerged when the Chagres Valley

was flooded to create Lake Gatun. The time to build the new

railway was now. The Railway

would allow the engineers to whisk the equipment rapidly to

any part of the canal that needed it. That enabled

them to get by with less equipment. Stevens used the

savings to purchase modern earth-moving and excavating

equipment. Just as important, Stevens developed a

rail-based system for disposing of the soil from the

excavations.

With the railway

completed, Stevens began work on a scale

never before witnessed. Gigantic Bucyrus steam shovels scooped

tons of earth from the Big Ditch. Soon railroad cars ran continuously on a double track,

dumping the tailings to form the Chagres Dam that would one

day create the Big Bathtub, aka Lake Gatun. Things worked like

clockwork under Stevens. Dig, put the dirt on the train, take

it to the dam, come back for more.

The men

respected Stevens immensely. His concern for their

welfare impressed them greatly. His humbleness and

lack of airs impressed them as well. Lacking the advanced

degrees of many of his colleagues, Stevens shunned any special

treatment as an officer. Stevens could have cared less about

comfort. The attractive living quarters used by his

predecessor remained empty as Stevens bunked nearer to

the workers.

This

hard-working, no-nonsense man had come to Panama at a time

when the project seemed doomed to the same failure that had

haunted the French. Stevens had turned the entire

project around and gotten it on track.

In November, 1906, Roosevelt himself visited the canal.

Roosevelt was amazed by the difference. He posed

proudly at

the controls of a giant Bucyrus shovel. He left Panama with a

smile on his face. Thanks to Stevens, now it seemed that the project could

not fail.

A Punch

to the Gut

Then came the blow.

Out of nowhere Chief Engineer Stevens abruptly resigned. It was February

12, 1907.

A pall came over the

camp. Just like that, their highly-respected leader was gone.

Stevens gave no explanation. He simply said it was time to go.

Stevens meant what he said. He left the next day.

Everyone was dumbfounded. No one had a clue what Stevens was

upset about or what his reason was for leaving. A huge cloud

of depression fell over the men. They had the wind knocked out

of them.

When he got the bad

news, Roosevelt was fit to be

tied. He had gone way out on a limb hiring a man with zero

experience at building canals. He had taken a lot of

heat for allowing Stevens to try his risky lock-based Canal.

The critics had a field day with that one.

Roosevelt took more political heat

when he justified Stevens' decision to concentrate on the

infrastructure. 'Build first, dig later' might make sense to

the insiders, but the American public was clamoring for results.

Now just as the focus of

the work had finally turned to construction of the canal

itself, his hand-picked man had just thrown in the towel.

The work had come to a disheartening slowdown until Stevens

could be replaced.

It was a shame to lose

Stevens because he was such an effective administrator. The

true reasons for his resignation were never revealed.

Burn-out, of course, was the most likely explanation. Another

theory was that since the time had come to work on the locks,

Stevens may have bowed out to let a man with more

experience in lock-building take over. Still, most

professionals

allow time for the new man to come aboard and get acclimated.

The abruptness of Stevens departure hinted at exhaustion... or maybe

something worse.

Now people began to

wonder. All sorts of paranoid theories were suggested.

Was he sick? Did Stevens suddenly realize the lock-based

system had no chance of working? Was he leaving to avoid shame

of some sort?

Whatever the reason, it

didn't matter. Stevens was gone. The loss affected

Roosevelt terribly. Roosevelt had let his guard down.

And why not? It seemed like the project was out of danger.

But now just when the project seemed to be in the clear, it was in serious trouble again.

Roosevelt frowned.

He wondered if there really was a curse over this canal project as

some people suggested. Maybe he didn't need another engineer.

Maybe what he needed was a witch doctor.

Stevens'

departure could not have come at a worse time. The

American public was fed up with the apparent lack of

progress. They didn't understand why Stevens had been

on the job for almost three years without doing any digging at

all. Roosevelt's opponents took the mysterious

resignation as a sign that Stevens had decided the canal

project was doomed to failure. Maybe Stevens had

discovered the locks system

wouldn't work. Maybe the machinery wasn't up to the

task of all the necessary digging. Something had to be

wrong!!

There had to be