Otto I

and the

Holy Roman Empire

|

The vacuum in the Carolingian East left by Louis the

Child's death had been

solved by the election of Henry the Fowler to become

King of Germany. Now the transition to a new order was complete

and the Carolingian Empire was officially over.

The choice of Henry to take Conrad's place

heralded the beginning of the Ottonian dynasty.

Henry's son Otto I (912–973) inherited the Duchy of

Saxony and the kingship of the Germans upon his father's

death in 936.

Otto

the Great would reign as German king from 936 until his

death in 973. Otto proved to be a competent ruler. Once he solidified

his role as King of Germany, this meant the split between

East and West Francia was complete and irreversible.

Otto continued his father's work to unify all German tribes

into a single kingdom. He greatly expanded the king's powers

at the expense of the aristocracy. Through strategic

marriages and personal appointments, Otto installed members

of his own family to the kingdom's most important duchies.

This reduced the various dukes, who had previously been

co-equals with the king, into royal subjects under his

authority. Royal subjects maybe, but Loyal subjects

no. The bitterness they felt would be reflected in a

thousand year dance - the princes of Germany would always

deliberately keep their king weak for fear that a strong

king would curtail their influence.

|

Otto's next move was to transform the Roman Catholic Church in

Germany to strengthen the royal office and subjected its

clergy to his personal control. Otto then suggested to

the Pope that the church align itself with his powerful

kingdom.

The coronation of Otto I by Pope John XII in 962

marked a revival of the concept of a Christian emperor in

the west. Otto become the leader/founder of the Holy

Roman Empire when he was crowned emperor. Otto

fashioned himself as the "successor of Charlemagne".

Some historians refer to the coronation of Charlemagne as

the origin of the HRE, while others prefer the coronation

of Otto I as its beginning. If one dates the

start of the HRE to Charlemagne, it enjoyed a

Thousand Year run. If one dates the start to Otto I,

it was the beginning of an unbroken line of Holy Roman

emperors lasting for more than eight centuries.

Thanks to Charlemagne, the HRE had started in West Francia.

However, the coronation of Otto meant the center of

the HRE had flipped to East Francia, aka the

Kingdom of Germany.

The Kingdom of Germany and the HRE would

remain loosely synonymous for the next 800 years until its

dissolution in 1806 thanks to the decision of Napoleon. Although

the HRE included at times the Kingdom of

Italy, the Kingdom of Bohemia, and the Kingdom of Burgundy,

the core and largest

territory of the empire was always Germany.

Otto I, his son Otto II and grandson Otto III each

regarded the imperial crown as a mandate to control the

papacy. They dismissed popes at their will and installed

replacements more to their liking. This power, together

with territories covering much of central Europe, gave the

German empire and the imperial title great prestige in the

late 10th century.

But subservience was not what the Pope had in mind when the

Pope John XII reinstated the Holy Roman Empire.

Over the next eight centuries, there would be many showdowns.

Here in America, our founding fathers had the wisdom to keep

the church and the state separate. The Europeans had

no such luck. Politics are difficult enough as it is,

but when religion becomes intricately entwined with

politics, things can get very confused.

The power struggles between the various Kings of Germany, aka the

"Emperors of the HRE" and the various popes over the

centuries helped turn Germany into a complete mess.

|

The

Holy Roman Empire began in 962 and ended in 1806. In

this snapshot from 1000 AD, one can see the rough outline of

today's modern German nation.

|

Weakness of

the Emperor

|

So what exactly was the

Holy Roman Empire?? Good question, but very tough to answer.

The Holy

Roman Empire was a strange political

entity.

The HRE

was not a highly centralized state like most

countries today. Instead, the HRE came to be

divided into dozens — eventually even HUNDREDS — of

individual political units governed by kings,

dukes, counts, bishops, archbishops, abbots, and

princes.

Strangely

enough, the German people came up with a system

where the King of Germany was "elected".

Has anyone ever heard of a King being elected?

It started when

the throne of East Francia was vacated with no valid

heir. Once Louis the Child died, that

forced the Princes, the rulers of the duchies and

therefore the next level of power in Germany... to

pick someone to be their ruler.

After Conrad

of Franconia was

ELECTED

to take the place of Louis the Child, this

set the precedent to

ELECT

Henry the Fowler as well. From that

point on, unlike the Kings of other European countries who simply

inherited the crown, a German King had to be

"elected" to office by a council of elite German princes.

After Otto

the Great ran roughshod over the Princes, they

thought twice about this new system. The

German Princes decided amongst themselves that

limiting the powers of the "King" was in their own

best interests. One needs to remember that all

people fear the rule of tyrants. For example,

the main reason Julius Caesar was assassinated was

due to fear over his increasing power.

So the German

Princes made sure each new King would maintain the

decentralized system of states in Germany.

|

This odd

circumstance did indeed keep the Kings from being

more powerful than the Princes, but it was

unfortunate for the Kingdom of Germany because it

guaranteed the country would never become "unified".

Since Otto's

original idea was

to align East Francia with the Catholic

Church, the

new "Emperor" was usually German. Once

the new German

king was chosen, the current Pope would then

coronate the new king as the new Holy Roman Emperor.

The same lack

of real authority spilled over to the position of

"Holy Roman Emperor". After the new German

monarch realized he was in a restricted position as

the "King", he would discover his position as "Holy

Roman Emperor" was not very powerful either.

If anything,

interference from the Church made governing Germany

even harder. As time passed, the authority of

the "King and Emperor" to govern grew weaker and

weaker.

The Emperor was

expected to protect the Pope and the Church. Unfortunately,

over the 8 centuries of the HRE, the Emperor

would usually spend more time arguing with the

Pope than anything else.

|

The

Holy Roman Empire changed shape many times during its eight century

run with different territories coming and going, but the

Kingdom of Germany was always at the core. Since the

Emperor was typically "German", Germany and the HRE became

roughly synonymous.

|

Simony and the

Investiture Controversy

|

|

There is a legend that the Founding Fathers of America

studied the history of Europe carefully so they could avoid

the mistakes of the European political systems. Two

features in particular were changed. There would be no

kings... America would be a democracy... and there would be

no religious interference in matters of government (or vice

versa).

Surely the story of the power struggles between the Roman

Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire was the major

reason that led to the

decision to keep the Church separate from the State here in

America.

Medieval times were often called the "Dark

Ages" for a reason. There were incredibly cruel and

horrible things done that defy understanding. Not that

we have evolved all that much... there is still war, murder

and corruption aplenty going on today. Nevertheless,

many things were done back in those days that we would term

"excessive" now.

|

Anyone who has studied the history of the Roman Catholic Church knows full

well there are shameful stories aplenty.

In particular, many of the abuses - genocide against people

of other religions, torture - were

done either by the Church itself or by representatives

acting in the "Name of God". "Spanish

Inquisition", the suppression of knowledge

(think Galileo), and the Crusades are prime examples.

On the other hand, the Roman Catholic Church has done a

great deal of good as well. The Church has played an

enormous role in bringing the valuable teachings of Jesus to

the Western Civilization.

The Church took a noble stand against slavery.

And many times it was the Church who protected the weak by

acting as the only check on the abuse of powers by evil

kings. When it came down to abuse of powers, there

have been some European rulers who would have stopped at

nothing were it not for the Church standing in their way.

The Holy Roman Empire was fertile ground for power struggles

between the Church and the German rulers. There were

all kinds of inherent conflicts built into the system.

The story of the 800 year Holy Empire could be boiled down

to a three ring circus between the Pope, the Holy Roman

Emperor, and the German princes who learned to gang up on

whichever side was not currently acting in their preferred

interests.

When Otto I got

himself declared "Holy Roman Emperor" in 962, he

fully expected to have his way with the Popes.

|

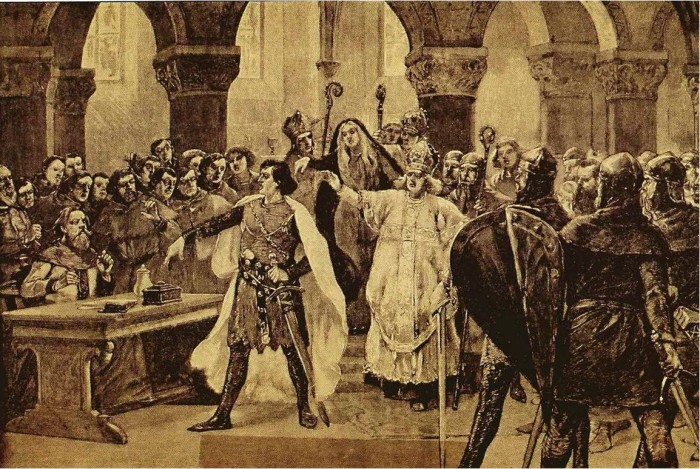

German

Princes making their wishes known to the Emperor. For

the entire reign of the Holy Roman Empire, by pursuing their

own individual interests, it was the German princes who

played a key role in limiting the Emperor's authority and

keeping Germany divided.

|

And that is

pretty much how it went down at first.

The Emperors had

their way with the Popes for the first hundred years

of the system put in play by Otto I. The

Church was rich beyond belief and the Emperors

exploited the wealth any way they could.

One of their

favorite tricks was Simony. Simony was the

act of selling church offices and roles.

Since a

substantial amount of wealth and land was usually

associated with the office of a bishop or abbot,

the sale of Church offices (a practice known as

simony) was an important source of income for

leaders among the nobility. It wasn't just the

nobility who owned the land. By charity, the

nobility donated the land that allowed the building

of churches and cathedrals. After that, the Church

owned the land. Over time, the Church had acquired

extensive property of its own and had grown greatly

in power.

The Church was

able to place itself in the middle of all affairs in

the daily life of the people. Frequently the

bishops were regarded for legal purposes as lords,

and some bishops had extraordinary political powers.

They made many daily decisions that greatly affected

the business practices and personal lives of the

people in their realm. In addition, some

bishops even had the power to decide who the next

Emperor would be. For example, three bishops

were among the seven men who elected emperors of the

Holy Roman Empire.

The result was

that the nobles as political authorities saw great

importance in having bishops who were politically

aligned with their interests. There had always

been a principle that the Church chose its own

bishops.

The purchase

of ecclesiastical authority was a sin called "simony".

And why was it

a sin??

In a nutshell,

the widespread practice of Simony deprived the Popes

of much of their authority.

Since priests

who were outside the ruling nobility did not earn

substantial wealth or have the ability to pass their inheritance on,

they would be difficult to sway by greed and power.

Their decisions would be fair and their jobs

would depend on answering to the Pope.

On the other

hand, it was beneficial for a ruler or nobleman to

appoint or sell the office to someone who would be

"loyal", which is another way of saying maybe the

people he appointed would be willing to let the

ruler get away with murder... literally.

Even before

Otto came along, the practice of simony became

widely accepted, sin or no sin. As we saw in

the crazy tale of Lothair II, Hucbert, the brother

of Teuberga, was not only a sinning,

bullying soldier, he just happened to also be an

abbot . Ghunter and Thietgaud, the men who

presided over the trial of Teutberga, were not only

Archbishops, they were also relations

of Waldrada. These men had all purchased

their positions of authority within the church.

The story of

Hucbert et all shows the practice

of simony was well-entrenched even before

Otto came along to reestablish the position of Holy

Roman Emperor.

Otto I

versus Pope John XII

Otto added a

new feature. Otto made sure the Emperor chose

the Pope and not vice versa. The Pope-elect was

required to issue an oath of allegiance to the

Emperor before his confirmation as Pope. If

the Emperor didn't like the Pope, he would get rid

of him.

Almost

immediately, Pope John XII regretted his decision to

empower Otto. He began to fear the Emperor's

rising power in Italy and began secret negotiations

a nobleman named Berengar to depose Otto. The

Pope also sent envoys to the Hungarians and the

Byzantine Empire to join him in an alliance against

the Emperor. Otto discovered the Pope’s plot and,

after defeating and imprisoning Berengar, marched on

Rome.

John XII fled

from Rome, and Otto, upon his arrival in Rome,

summoned a council and deposed John XII as Pope,

appointing Leo VIII as his successor.

Otto returned to Germany by the end of 963,

confident his rule in Italy and within Rome was

secure. However, the moment he was gone, John

XII began stirring up trouble behind him. The

Roman populace considered Leo VIII, a layman with no

former ecclesiastical training and loyal to Otto,

unacceptable as Pope.

In February

964, at the provocations of John XII, the Roman

people forced Leo VIII to flee the city. Leo VIII

was deposed and John XII was restored to the chair

of St. Peter.

When John XII

died suddenly in May 964, the Romans elected Pope

Benedict V as his successor.

Upon hearing of

the Romans’ actions, Otto mobilized his army and

returned to Italy. After marching on Rome and laying

siege to the city in June 964, Otto compelled the

Romans to accept his appointee Leo VIII as Pope and

exiled Benedict V.

Otto had proven

who was in charge. He had the army.

Whatever Otto wanted, Otto got.

If Otto wanted

the practice of simony to continue, then it would

continue. The consequence was that now bishops

and abbots continued to usually part of the ruling

nobility themselves.

The German Princes

The practice of

simony posed a real problem for the Pope. It

meant that practically every appointment on his

staff was out of his control. It meant that

most of his administrative staff was more loyal to

the Emperor or to local nobles than to him.

Although

history typically concentrates on the key players

such as the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope, the

German princes, aka "the nobility" were actively

involved in the ongoing conflicts.

The fascinating

thing about this whole scenario is that the nobility

was just as much a player as the Emperor and the

Pope. Because both the Emperor and Pope were

elected positions, once the nobility discovered that

they had quite a bit of say-so in which particular

man got elected and which didn't, they turned into

spoiled brats. Like kids

who play Mom and Pop against each other, over time

the nobility found that they had the ability to get

what they wanted by exploiting the vulnerabilities

of the men who wished to occupy vacancies in the seat of power.

The practice of

simony was of extreme importance to both the Emperor

and the nobles. Not only could a King or a noble

acquire large sums of money from selling high church

appointments, he could put friends in high places

who were loyal to him.

The nobility

developed a clever trick. Literacy was a

pre-requisite to obtaining a church appointment.

However, education was also quite rare in those times. So the nobles

developed a system whereby the older siblings in the

family would inherit the land and titles while the younger sons

of the nobility were assigned the task of learning to

read and acquire religious training. When the time

came, someone in the family would be prepared to be

appointed as bishop or abbot.

As one might

gather, there was a huge premium on having big,

strapping healthy boys. Only boys could be

kings. Only boys could be warriors. Only

boys could find positions of importance in the

Church. Only boys could inherit lands.

People died

young in those days. Life spans weren't very long. The

big problem was that disease held a vastly upper

hand to knowledge. Sanitation was poor.

Plague was a constant threat. Infection was a

danger. One fever could end things quickly.

Therefore everyone wanted

to have lots of boys in case

some of them died in war or to disease.

Furthermore,

having children was a real headache. As we saw

in the case of our friend Teutberga coming up

barren, many arranged marriages saw men trapped to

women who could not bear children. For

example, Anne of Austria, wife to France's Louis

III, spent twenty-three years of marriage trying to

produce an heir. After four miscarriages, Anne

finally gave birth to a son, the future Louis XIV.

The birth was considered a "miracle" at the time,

but more likely Anne discretely switched to another

man in her desperation to fulfill her duty.

Giving birth

was serious business. Due to poor sanitary habits, child birth often resulted in the death of

the child or death of the mother or both. Furthermore,

having a healthy, intelligent boy was a lot harder

than one might imagine. The health of the

child was never taken for granted. Due to

ignorance about the dangers of inbreeding, cousins

married all the time. The result was that many

royal

children were sickly, deformed, and oft times moronic.

The Church didn't make

things any easier by prohibiting divorce (e.g. Henry

VIII of England and his shenanigans of getting rid of one wife

after another trying to have a male heir).

Bottom Line: Due to the

difficulty having a healthy male child with a good head

on his shoulders, hereditary lines died out all the time.

For example, Otto I

became Emperor in 962. He was

succeeded as Emperor by Otto II by Otto III by

Henry

II and then his line died out in 1024. Four

men lasted a sum total of of 42. Men simply

didn't live very long in those days. In only

42 years, the line established by Otto I was gone.

What to do?

Elect a new line. Note the key word "elect".

Here is an opportunity where the German Princes

could sell their votes to the highest bidder.

In other words, the German Kings were often just

barely more powerful than the Princes themselves.

Henry

III and Benedict IX

After the

Saxon-based Ottonian dynasty of emperors died off

thanks to the childless Emperor Henry II, Conrad

II was elected to succeed him as King in 1024 at

the age of 34. Conrad founded his own dynasty of

rulers. Known as the Salian dynasty,

this line lasted 111 years before it too died off.

The Salian line included four men -

Conrad, Henry III,

Henry IV, and Henry V - who

ruled the Holy Roman Empire from 1024 to 1135.

After Conrad

came Henry III in 1046. Henry

III (1017-1056) presided over perhaps the

strangest era in Papal history. The story of

Henry III would set the stage for one of the most

important personal showdowns in European history.

Of course, this

story about the History of Germany has been a long one,

but we really do need to stop here and

take a close look at the remarkable story of a truly

despicable Pope. Benedict IX was remarkable all right, but not in the normal

sense. Despite a legion

of some really bad Popes to pick from, Benedict IX

is considered one of the Ten Worst Popes in

history.

Let's read some

of Benedict's press clippings.

•

St. Peter

Damian is alleged to have described him as

"feasting on immorality", accusing him of

routine homosexuality and bestiality. Benedict

was said to be

the first pope to have been primarily

homosexual. He was said to have held orgies in the

Lateran palace.

•

Papal historian Ferdinand Gregorovius wrote

about Benedict, "It seemed as if a demon from hell,

in the disguise of a priest, occupied the chair

of Peter and profaned the sacred mysteries of

religion by his insolent courses."

•

The Catholic Encyclopedia calls him "a disgrace

to the Chair of Peter."

•

Benedict

was accused by Bishop Benno of Piacenza of

"many vile adulteries and murders".

•

Pope Victor III, in his third book of Dialogues,

referred to Benedict in this way: "his rapes, murders and other

unspeakable acts. His life as a pope was so

vile, so foul, so execrable, that I shudder to

think of it."

Benedict IX

holds several strange records. He was the only

man ever to be Pope twice. In fact, Benedict

was Pope three times and narrowly missed at a fourth

shot!!

Benedict holds

another dubious record - he is the only Pope to ever

sell his position! Even more bizarre, he did

it twice!

As pointed out

earlier, Benedict is the only man to have served as

Pope for three discontinuous periods. He was

Pope for 12 years from 1032 to 1044. Benedict

gave up his papacy the first time in exchange for a

large sum of money in 1044 to Pope Sylvester.

Benedict

returned in 1045 to depose his replacement

Sylvester. He stuck around and reigned for one

month. Then

Benedict left again, possibly to marry. Now he

sold the papacy for a second time in 1045, this time to

Gregory, his godfather.

Two years

later, Benedict was back again. This time he

ruled

from 1047 to 1048.

So how did

Benedict get away with this shameful behavior?

Or for that matter, how did Benedict get elected in

the first place?

The answer is a

bit of a mystery, but the most likely reason was

that Conrad II, the emperor at the time (1032), was

preoccupied with his own problems up in Germany 1,000 miles away.

Let us not forget that travel was measured in weeks,

not days. So with Conrad out of the picture,

Roman politics kicked in. Benedict was not

only the nephew of two previous pope, he was also

the son of a very powerful Roman family. So

Benedict got the nod in 1032.

In 1039, out of

the blue, all sorts of European rulers started

dying.

First Conrad

II died

unexpectedly. Immediately his son Henry III took

over. With more rulers dying right and

left, in short order Henry became a triple-duke

(Bavaria, Swabia, and Carinthia) and triple-king

(Germany, Burgundy, and Italy). Henry, 22 at

the time, quickly found himself immersed in putting out fires throughout his

kingdoms in

Europe. Henry III was so preoccupied, it took

him seven years before he finally got around to

paying attention to the problems in Rome.

Meanwhile

Benedict IX was making a disgrace out of his

position. In 1045, when

Benedict sold his papacy for the second time, once Henry

III got the news, Henry decided the time had come to step in.

In 1046, Henry

III traveled down to Rome and fired all

three of the clowns - Benedict IX, Sylvester III,

and Gregory VI - and took the time to find one he liked in

Pope

Clement II.

Shortly after

Clement had been appointed Pope,

Clement turned around and crowned Henry III to the position of Holy

Roman Emperor in 1946. This filled the vacancy

that had lasted for seven years since Conrad's

death. Satisfied the Church was finally in good hands,

Henry left Italy and headed back to Germany.

Clement II was

indeed a good man. Only one problem.

Clement was busy making plans

for reform when he

died suddenly two years into his reign.

Considering Clement had been in perfect health,

everyone suspected that Pope Clement II had been poisoned.

As it turns out, they were absolutely right. A toxicologic examination of his remains in the

mid-20th century confirmed the centuries-old rumors that

the Pope had indeed been poisoned with lead sugar.

Now who would

do a thing like this? Well, Suspect Number One

would have to be Benedict

IX, the man who had been fired by Henry III.

After all, Benedict had the most to gain.

Interestingly, once Benedict IX noticed there was a

Papal opening, he campaigned to take Clement's place.

Sure enough, that's

exactly what happened. With Henry III

in Germany, during the time it took Church officials

to send word to Henry and ask what to do next, our favorite

anti-pope Benedict IX

stepped into the vacuum and became Pope again. Benedict

would reign for one year until 1048.

A religious

leader named Poppo of

Brixen eventually forced Benedict out of Rome.

Poppo became the next pope under the name Damasus

II. Only one problem...

Damasus II

lasted as Pope for all of 23 days.

And then he died.

Three weeks.

Hmm. That was kind of fast. Does the reader

have a suspicious mind?

•

Fact

One: Benedict was said to be a highly

immoral man, a person who showed little respect

for the Church he was supposed to serve.

•

Fact Two:

Two of the shortest papal tenures in history

occurred while

Benedict, one of the absolute worst popes in

history, was hanging around Rome.

•

Fact Three:

It has been proven that one of those Popes was

poisoned.

•

Fact

Four: Poppo's worst enemy was

Benedict.

Given the

(correct) belief that Clement had been poisoned, it

didn't take much to suspect further foul play.

Whenever Benedict was around, popes had a strange

way of dying.

This set of

circumstances gave rise to rumors that Poppo was

also poisoned. The finger was pointed at Gerhard Brazutus, a

good friend of Benedict IX, as a likely suspect.

It did not help

that with Poppo/Damasus out of the way, Benedict

began attempts to

regain the Papal Throne for the fourth time.

This led people to speculate that Benedict had Poppo poisoned

not just for revenge, but also so Benedict could become

Pope yet again.

Benedict was

unsuccessful in landing a fourth term thanks to the

looming shadow of Henry III from afar. Instead

the papacy

remained empty for a year until Henry could find the

right man. In 1049 Henry III stepped back in

and appointed Leo IX, a man widely considered

the most historically significant German Pope of the

Middle Ages. Leo was so excellent that he would later be

declared a saint.

Pope Leo IX was

a reform Pope. Besides his condemnation of

clerical marriage, his stand against simony and the

loss of the church's properties meant that he was

serious about solving the most serious problems of

the Church. Unfortunately, Leo died before he

could see his work carried out. His term

lasted only five years until his death in 1054.

Leo was

succeeded by Pope Victor II in 1055. Victor

was a kinsman and friend to Henry. Like

Clement and Leo before him, Victor was also a good

man. Like Leo before him, Victor was also a

reform Pope and Victor also condemned the practice

of simony... which was rather ironic because Victor

owed his position to simony in the first place.

Victor would be

at his friend's side at Henry's deathbed.

Sadly, Pope Victor

lived only one more year after Henry III's death.

As we shall see, this odd circumstance would prove

to be very significant.

Henry's legacy

was a strange one. On the one hand, Henry III had

been one of the most powerful of all the Holy Roman

Emperors. His authority as king in Burgundy,

Germany, and Italy was only rarely questioned.

His ostensible relationship with the Church was termed a

positive one. Henry was not responsible for

Benedict at all; Benedict was appointed by his

father Conrad. Once the insanity in Rome became

apparent, Henry replaced Benedict. In fact, Henry not only got rid of

Benedict, his three choices for Pope - Clement, Leo,

and Victor - had all been good men.

It wasn't

Henry's fault that Pope Benedict turned out to be a

serial killer.

The

Catholic Church Makes its Move

Henry III's

relationship with the Church is often pronounced a

failure in that he apparently left problems far

beyond the capacities of his successors to handle.

Henry knew about these problems in the Church and

basically ignored them. During Henry's 17 year

reign, many times Henry chose not to leave Germany

in case there might be an uprising during his

absence. His constant absence allowed huge

problems in the Church to grow unchecked.

Meanwhile the

Church was having a bad run of luck. Previous

Papal elections had been effectively controlled by

the Roman aristocracy, unless the Emperor was strong

enough to be able to intervene from a distance to

impose his will. However, the insanity of

Benedict's disgraceful reign had made it clear the

current system of selecting Popes was not working.

Unfortunately,

Benedict's replacements Clement,

Leo, and Victor had all died before they could enact

the much-needed reforms.

Now, however,

that luck was about to change. Henry III's

death gave the Church a rare opportunity to make a

significant change.

Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII

What a story.

Henry IV

(1050–1106), son of Henry III, had ascended to King of

the Germans in 1056 at the age of six.

However, his mother Agnes would rule as Regent until

he came of age.

There had been

six new popes since the embarrassment of Benedict.

Each man pope had

fretted about the problem of simony. They knew

full well there was so much

in the Church that needed to change, but how?

An opportunity

came in 1056 when Henry III died and Henry IV became

German king at six years of age.

The reformers

knew that as long as the emperor maintained the

ability to appoint the pope, they would never be

able to take control of their own house. So their

first step was to forcibly gain the papacy from the

control of the emperor. The reformers seized

the opportunity to take the papacy by force while

Henry was still a child and could not react.

In 1059 a church council in Rome declared that

leaders of the nobility would no longer have any

part in the selection of popes. They created

the College of Cardinals as a body of

electors made up entirely of church officials.

Now in control

of electing their own pope, the College of Cardinals

could carefully choose the right man to lead them.

Running on a

parallel path to Henry IV was a Tuscan priest

named Hildebrand (1015-1085). In 1073,

the charismatic Hildebrand became Pope

Gregory VII. He was 58 at the time.

Hildebrand was destined to change the course of

history. During his 12-year term, Pope Gregory

VII would become one of the greatest popes to ever occupy

the papal throne; he was a true reformer who acted

out of religious zeal. He would become the man

who did something about simony.

In 1075, that

parallel course turned into a collision course

instead when Pope Gregory decreed that the Pope

alone could appoint or depose churchmen.

Gregory had decided to forcefully taking the power

of "investiture", the act of appointing bishops from

the Holy Roman Emperor and place that power wholly

within control of the Church. This began the

Investiture Controversy.

By this

time, Henry IV was no longer a child.

Henry reacted to this declaration by sending

Gregory VII an angry letter in which he

withdrew his imperial support of Gregory as

Pope in no uncertain terms.

The

letter began "Henry, king not through

usurpation but through the holy ordination

of God, to Hildebrand, at present not pope

but false monk". It called for the

election of a new Pope. His letter ends, "I,

Henry, king by the grace of God, with all of

my Bishops, say to you, come down, come

down, and be damned throughout the ages."

Henry

defied Gregory and continued to appoint his

own bishops. In other words, Henry IV

was going to continue to sell church

appointments whether Gregory liked it or not

and Henry intended to remove Gregory from

office for good measure.

The

situation came to a head when Henry IV

installed his chaplain, Tedald, as Bishop of

Milan, when another priest of Milan, Atto,

had already been chosen in Rome by the pope

for candidacy.

In 1076

Gregory responded by excommunicating Henry,

removing him from the Church and deposing

(i.e. removing) him as German king.

|

Pope

Gregory VII excommunicating Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV

|

|

After much

bluster on both sides, the advantage gradually came

to the side of Gregory VII because the German

princes and the aristocracy saw a great opportunity.

Happy to hear of the king's removal as "Emperor",

they used religious reasons to continue a major

rebellion started in 1075.

This began a

seizure of royal holdings. Aristocrats claimed

local lordships over peasants and property, built

forts (which had previously been outlawed) and built

up localized fiefdoms to secure their autonomy from

the empire.

Seeing his

empire disintegrate, Henry IV had no choice but to

back down. He needed time to marshal his

forces to fight the rebellion in his homeland.

So in 1077 Henry IV traveled to Canossa in northern

Italy to meet the Pope and apologize in person.

It was a famous moment because it marked the first

time an Emperor had ever given in to the authority

of the Pope.

By pitting the

nobility against the King/Emperor, Gregory had

finally found a way to check the previously

undisputed control of the Emperor. Emperor Henry IV

had been one of the most powerful men in Europe.

Now he was forced to spend the rest of his life

dealing with people who were suddenly willing to

give him problems.

Amazingly, the

Church had finally gained the upper hand.

However, the fight wasn't over. The conflict

between Emperor Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII was

only the early part of the Investiture Controversy.

That controversy would be continued by later kings,

emperors, and popes for several centuries.

|

| |

Frederick Barbarossa

|

|

When Frederick I (1122-1190),

previously Frederick Barbarossa of

Hohenstaufen, was chosen as king in 1152,

royal power had been in effective abeyance

to a considerable degree for more than

eighty years. The Germany that

Frederick had inherited was a patchwork of

more than 1600 individual states, each with

its own prince. A few of these states such

as Bavaria and Saxony were large, but many

were too small to even pinpoint on a map.

This

ridiculous situation was a direct

consequence of the fight between Henry IV

and Pope Gregory. The reigns of

Henry IV and and his son Henry V

left the status of the German empire in

complete disarray, its power waning under

the weight of the Investiture Controversy.

The

German monarchy had become a nominal title

with no real power. The king was chosen by

the princes, he was given no resources

outside those of his own duchy, and he was

prevented from exercising any real authority

or leadership in the realm.

Once

the supreme authority of the German King/

Holy Roman Emperor had been shattered, the

various princes and nobles began to fight

amongst themselves as well as prey upon the

weak. They seized every chance they

could to grab new chunks of land. As

civil wars broke out throughout the land,

Germany became increasingly subdivided.

The

Germany Frederick Barbarossa inherited was

in a state of constant civil war.

Frederick made it his goal to put an end to

this fighting. However, it wouldn't be

easy. The German princes, far from being

subordinated to royal control, were

intensifying their hold on wealth and power

in Germany and entrenching their positions.

|

When Frederick came to the throne, the

prospects for the revival of German imperial

power were extremely thin. The great German

princes had increased their power and land

holdings. The king had been left with only

the traditional family domains and a vestige

of power over the bishops and abbeys. The

backwash of the Investiture controversy had

left the German states in continuous

turmoil. Rival states were in perpetual war.

These conditions allowed Frederick to be an

occasional peace-maker.

Interestingly, Barbarossa did not use force

to end the fighting, but rather diplomacy.

Frederick was a pragmatist who dealt with

the princes by finding areas of mutual

self-interest. Using his natural gifts

of mediation and his family ties, Barbarossa

was able to unite the various warring

Germanic factions and create peace.

To be

able to patch Germany back together again

simply through the force of his own

personality was asking a bit much, but

Barbarossa was largely successful.

Frederick's charisma led to a fantastic

juggling act in which he settled squabble

after squabble mainly through negotiation.

Working his magic over a quarter of a

century, Frederick restored the imperial

authority in the German states.

That

said, in the end, Frederick failed to

achieve his dream of a Central European

Empire. He really never had a chance -

his enemies were far too formidable to force

them to actually unite, especially with the

Pope constantly using his tricks to turn

various Princes against Barbarossa. But at least

Frederick was able to get the various powers

to cooperate and stop fighting.

Therefore Frederick left behind a legacy of

a strong ruler who was able to create peace.

Frederick II, Barbarossa's grandson, did a

good job of continuing the balancing act.

By playing the various German states against

each other, the lions stayed largely in

check. The 100 year period of the two

Fredericks was largely a time of peace in

the German realm.

This

changed abruptly after the death of

Friedrich II. Germany again plunged

into civil war when Frederick's Hohenstaufen

rule ended. The sovereign rulers of the

empire's various regions began anew to

quarrel over property rights and there was

no one to mediate. Thanks to constant

war, the economy and culture of the area

lagged greatly behind the rest of Europe. Then

came the worst curse of all when the Black

Death pandemic swept through Europe.

In some areas, up to one-third of the

population died off.

On the

surface, it appeared the Church had won the

long struggle. However, from this point on,

the Church overplayed its hand. The people

of Europe watched as one pope after another

used his office for political reasons rather

than spiritual reasons. As a result,

confidence in the position of the pope

declined steadily over time. The constant

involvement of various popes in worldly

matters sowed the seeds of rebellion against

the authority of the Church.

With

the passing of Frederick Barbarossa and his

grandson, Germany lay shattered. Germany would remain in pieces for

another 600 years.

During

these harsh times, the constant suffering

created a longing among the people for the

days of the bygone dynasty and the great

red-bearded leader. After a few centuries of

passing on his legend by word of mouth,

Frederick I became commonly known as "Barbarossa".

By the 16th century the legend of "Barbarossa"

had become quite elaborate, quite possibly

outstripping the man's actual

accomplishments. The name

"Barbarossa" had become the symbol of the general

population's growing desire for a united Germany.

The Barbarossa cult became even more

pronounced in the late 19th century.

William I, the eventual founder of the

German Empire, is said to have benefited

greatly from the legacy of Frederick

Barbarossa.

|

|

|

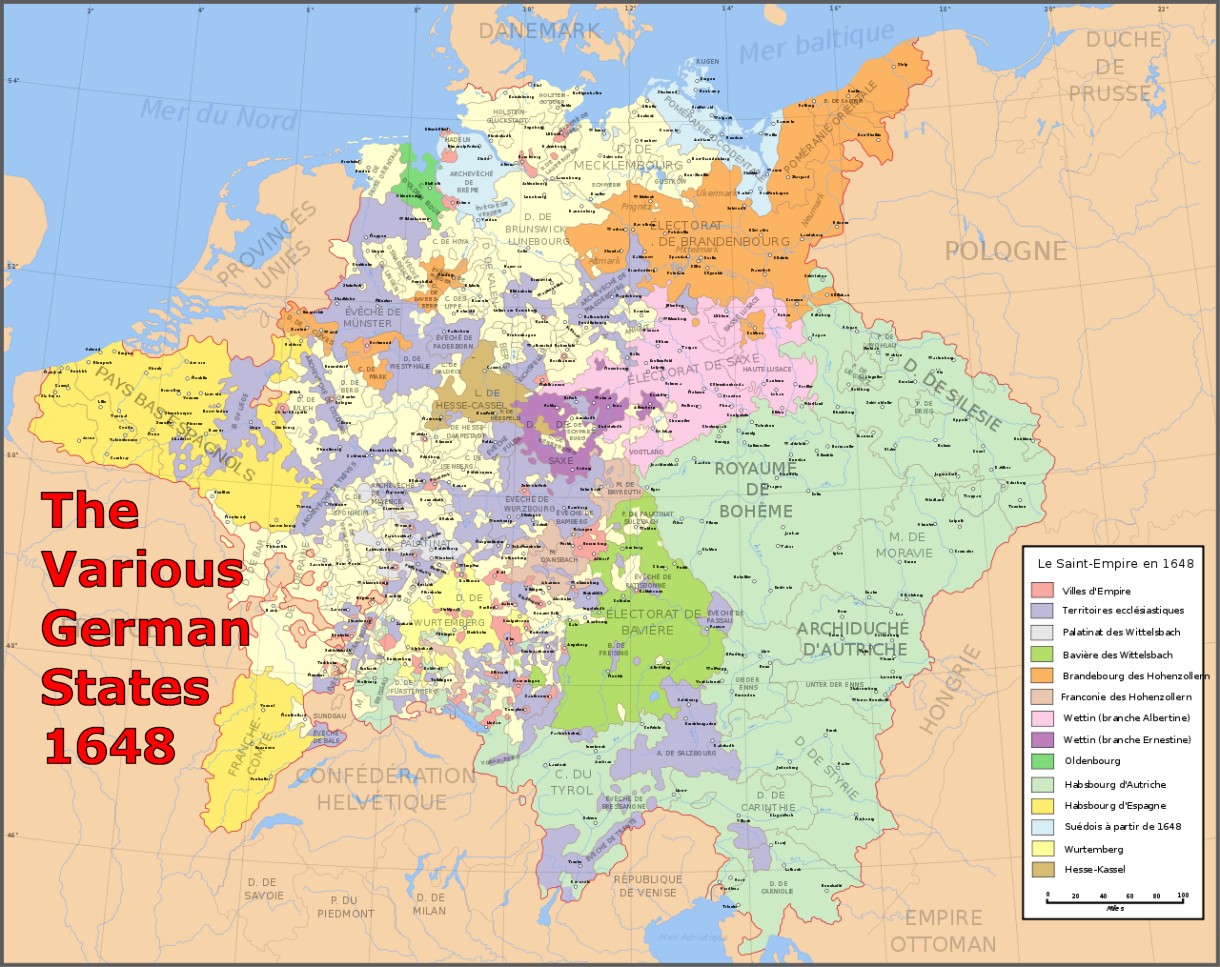

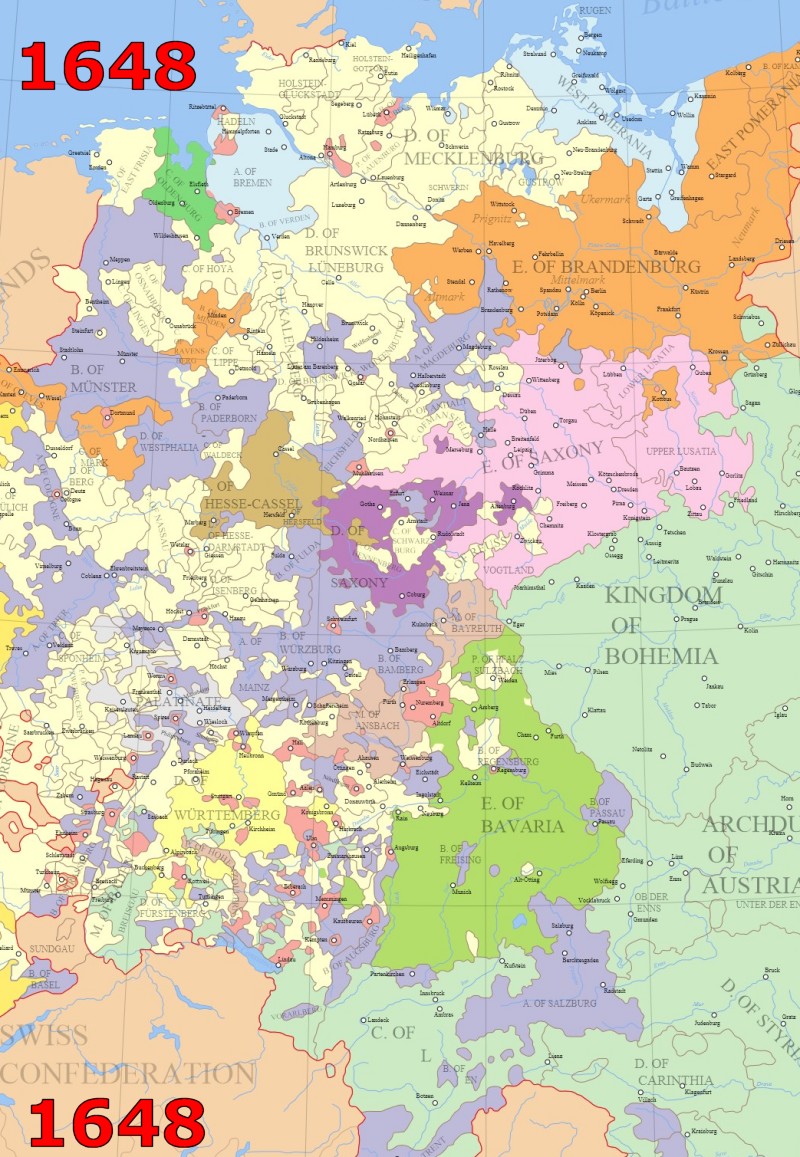

The Germany of

Frederick Barbarossa's day (1152) was said to be divided into 1600

individual states. This 1648 map suggests that Germany

continues to be subdivided into a vast number of separate entities

that are basically independent nation-states.

Take note that

much of Germany belonged to the Church. All those "territoires

ecclesiastiques" colored in mauve are church property.

Also note that

these small, divided nation states are ripe for conquest by the larger states

surrounding them such as Austria, Poland, France, Denmark, and

Sweden. Divided Germany was something of a sitting duck.

Patchwork Germany

|

What a mess. Back in the days of Otto I, no one ever

foresaw these problems. From Otto's point of view, the

Emperor would always be in charge. However, the fact

that the seat of King/Emperor was an elected position became

an Achilles Heel.

Once Pope Gregory began the process of

eroding the Emperor's power, Frederick Barbarossa was the

last man to effectively challenge the Papal authority.

Once he was gone, the next 600 years of Emperors were all severely restricted by the

near-equal power of the various

Prince Electors. At no time could the Emperor simply

issue decrees and govern autonomously over the Empire.

The Emperor always had to answer to the German Princes.

From the High Middle Ages onwards, the

HRE was marked

by an uneasy coexistence of meddling popes and the princes of the local

territories who were always looking for ways to take power away from the

Emperor.

To a greater extent than in other medieval kingdoms such as

France and England, the Emperors were unable to gain much

control over the lands they 'formally owned', but were ruled

over by other leaders such as the Princes.

Furthermore, since the King and Emperor positions were "elected",

the Emperors were vulnerable to being voted out.

This

was crippling.

Now instead of consolidating the far-flung territories into a cohesive unit, Emperors were forced to grant more and

more autonomy to princes, nobles and bishops to

secure their position from a threat of being deposed.

|

This process had begun in the 11th century with the

Investiture Controversy. From that point on, each Emperor

struggled to regain the upper hand, but were thwarted both by

the papacy and by the princes of the Empire.

Germany began as an assemblage of a number of once separate

and independent people and kingdoms known as duchies.

When Louis the German took over East Francia in 843

after the Treaty of Verdun, the

area was subdivided into several sub-kingdoms known as "Stem

Duchies".

These duchies were essentially the

domains of the old Germanic tribes of the area that had

first settled there such as the Saxons (Saxony).

Bavaria was another stem duchy. Bavaria is one

of the oldest continuously existing states in Europe. It was

established as a stem duchy in the year 907. In the

17th century, the Duke of Bavaria became a Prince-elector of

the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

Within the large stem duchies, there were also hundreds of

small, German-speaking principalities. For example,

modern Bavaria includes parts of the historical regions of

Franconia, Upper Palatinate and Swabia.

These were all independent nation-states at some point in

time.

Oddly enough, medieval England and France once

looked the same way. They were just as divided as

Germany.

However, while England

and France used the power of the throne to become unified into

large, coherent

nations with central authority, the German lands remained

separate.

We have seen the difference boiled down to the weakness of the

Emperor.

He could be voted out of office. He couldn't

tell the princes what to do with their own lands.

At various points during the 800 years of the HRE, the

Emperor was more cheerleader than actual leader, more puppet

than potentate. He was forced to watch helplessly as

his "Empire" became increasingly chopped into bits and

pieces.

In the end, the problems in Germany could be attributed

directly to the constant interference of the Church and the

manipulation of the German princes.

Once the Church undermined the authority of the Emperor

starting with Henry IV, the princes became the real power.

Lacking any central authority, the inmates ruled the asylum.

The constant civil wars kept Germany separated.

Another problem was a process known as feudal fragmentation. Each

German nation-state had significant autonomy to the point

of outright independence. Each state was ruled by a high-ranking

noble such as a prince or a duke.

Feudal fragmentation occurs after the death of the

legitimate ruler who

leaves no clear heir. Fragmentation also occurs when the legitimate rule subdivides his

territory to several heirs.

Besides the large stem duchies, within them were hundreds of

small, German-speaking principalities, most of which derived

from successive dynastic splits.

Due to this bizarre system, other than war, the fast way to

grow a dynasty and acquire land was to MARRY someone else

with land and merge the territories.

Principalities were sometimes united through royal

marriages, but the resulting entity was often not a

contiguous territory. Princes might control two or

three

territories hundreds of miles apart.

The number of territories in the Empire was considerable,

rising to approximately 300 at the time of the 1648 Peace of

Westphalia. Many of these Kleinstaaten ("little states")

covered no more than a few square miles, or included several

non-contiguous pieces. The Empire was called a Flickenteppich ("patchwork carpet").

Over time, these small states modernized their military,

judicial, and economic administrations. These

institutions hardly existed

at the imperial level. The emperor was little more

than a feudalistic figurehead, a man without political or

military clout.

Many of the princes had better armies than the emperor.

This was by design; the princes did not wish to give up

control to a central leader.

If anyone had given this

any thought, they would see the lack of centralized

authority meant German lands were ripe for invasion.

United we stand, divided we fall.

Never in their wildest dreams

did the princes guess

their own Emperor would do something so stupid as to cripple

the Kingdom of Germany for the next two centuries.

|

1789

was the year of the French Revolution. As this map

indicates, over the past eight centuries, German territory

had been sliced and diced into something resembling Swiss

Cheese.

Estimates of the total number of German states at any given

time during the 18th century varies range from 294 to 348

separate nation-states. This crazy map gives a good idea

of just how fragmented Germany had become.

Although we are jumping ahead somewhat, note that the

important nation state of

Saxony

was now in the Habsburg Austrian domain. In the 18th

and 19th century, Austria was the dominant power. And

notice how large

Brandenburg

has become.

Below is the same

map enlarged.

In the

summer of 1789, young Wilhelm von Humboldt and some friends,

left Brunswick, capital of the Duchy of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel,

for France to observe the revolutionary events unfolding in

Paris.

Von

Humboldt wrote that he would need to enter and exit six duchies,

four bishoprics (land owned by the Church) and one Free Imperial City (Aachen) simply

to reach the French border.

See how long it takes you

to locate the

red star

on the map which marks his home

territory (Braunschweig). The struggle to locate the

red star will reflect

the absurdity of how complicated this map is.

|

Martin

Luther

|

One of the most important figures in European history was

Martin Luther. Martin Luther changed the world.

He also unwittingly got a lot of people killed in the

process.

Martin Luther (1483 - 1546) was a German monk, Catholic

priest, and professor of theology. Luther became the key figure

of a reform movement in 16th century Christianity known as the

Protestant Reformation.

The Investiture Controversy had reversed the abuses of

State power under "simony", the practice of selling high

church offices against the will of the church.

However, once the Church had the upper hand, the Church had begun to

abuse its own power as well. The Church had begun selling places in

Heaven!!

Current Roman Catholic theology stated that faith alone

could not guarantee man's place in Heaven. Justification

depended on charity and good works. The benefits of

good works could be obtained most easily by donating money

to the church. Luther didn't agree.

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to his bishop, Albert of

Mainz, protesting the sale of indulgences.

Among Luther's points was Thesis 86 which asked: "Why

does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth

of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with

the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?"

Luther also objected to a saying attributed to Johann Tetzel

that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul

from purgatory springs into heaven".

Luther insisted that forgiveness was God's alone to grant.

He added those who claimed that indulgences absolved

buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were

in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following

Christ on account of such false assurances.

Luther strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's

punishment for sin could be purchased with monetary values.

Luther taught that salvation and subsequently eternity in

heaven is not earned by good deeds but is received only as a

free gift of God's grace through faith in Jesus Christ as

redeemer from sin.

|

|

It should be no

surprise to learn that Luther had made a powerful

enemy. The Pope was incensed.

Luther's theology

had directly challenged the authority of the Pope of the

Roman Catholic Church by teaching that the Bible is the only

source of divinely revealed knowledge from God.

In 1520 Pope Leo X demanded Luther retract all of his

writings. Luther's refusal resulted in his excommunication

by the Pope.

Holy Roman

Emperor Charles V took note. This was his chance to protect the Church and the Papacy.

Charles

summoned Luther to a meeting to renounce or reaffirm his

views.

|

At the Imperial Diet of Worms on 28 January 1521,

Luther gave a brilliant defense of his ideas. His

presentation was so powerful that several leaders in the

audience were shocked to realize his ideas made actually sense.

They also could not believe the Church had been stupid enough to

give this brilliant man an open forum for his ideas.

It was common

knowledge that Luther's fate had been sealed long before this meeting even took place.

Luther was

surely a dead man. But maybe not.

Over the next five days, private

conferences were held to determine Luther's fate. Then

came the verdict.

The Emperor declared Luther an

outlaw, banned his literature, and ordered his arrest.

"We want Luther to be apprehended and punished as a notorious

heretic."

|

Martin Luther gives a brilliant explanation of his

ideas at the 1521 Diet of Worms

|

The problem was that Luther had

disappeared.

Now they had to find him. The verdict made it a crime for anyone in

Germany to give Luther food or shelter; it also permitted

anyone to kill Luther without legal consequence.

About the same

time as the verdict

was being read, Luther had been on the road walking home.

To his shock, he was accosted by masked horsemen who

insisted he come with them against his will.

As Luther would learn, it was all an act.

Prince Frederick, Duke of Saxony, had decided to

"kidnap" Luther for his own good. He made his

men appear as armed highwaymen to disguise his

involvement. In reality Frederick

was taking steps to protect Luther from certain

death. It was a brilliant move.

While in

captivity, Luther would write a German version of

the Bible. He would soon form his own Lutheran church

which led to the Protestant Reformation.

Centuries of

resentment towards the Catholic Church and its

abuses resulted in mass defections. Now that

people had a CHOICE of religion,

countless Protestant churches began to appear across

Germany. Overnight this new

religion would create a huge schism within Western Christianity.

Soon this schism would lead to the terrible European wars of

religion.

Martin Luther

had unwittingly brought the equivalent of a Biblical

Plague right to the doorstep of Germany. 7

million people were doomed to die in the religious

wars that would soon follow.

|

|

1618-1648: The Thirty Years

War

|

As if Germany didn't have enough problems already,

Germany was now further subdivided along religious lines. Martin Luther's Reformation in 1517 pitted the

religious beliefs of Catholics versus Protestants.

Germany had hundreds of rulers, some of them famous, most of

them forgotten. Every one of the rulers was either important or thought he was

important.

They wanted control and greatly resisted

external authority. They invariably coveted the lands of their

neighbors, but now they had a new excuse to fight:

Religion!!

The Reformation meant that many states within the

Catholic HRE

had suddenly become Protestant instead. The backlash was

predictable. Catholic rulers decided they had the God-given right to change the religion of their

neighbors by force.

The concept of religious tolerance simply did not exist back

in those times. Over the next century, states headed

by Roman Catholic dynasties faced those ruled by Protestant

dynasties in a seemingly neverending series of religious conflicts.

As far as Dynasties were concerned, there was one dynasty

that stood out above all others - the Roman Catholic Habsburg Family.

They controlled territory in Spain, Netherlands, Italy,

Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Bohemia.

The power base of the

Habsburg family had begun in Switzerland in the 1000s.

From there, the family had moved its power base to the Duchy

of Austria. Each century marked new acquisitions of

land.

At times the family used force to expand its territory, but

mainly it used a series of dynastic marriages to vastly

expand its domains. By marrying the rich to the rich

and rulers to the rulers, Burgundy, Spain, Hungary, Bohemia, and other territories

all came by inheritance.

The House of Habsburg produced

kings of various Dutch and Italian countries, Spain, Bohemia, England, Germany, Hungary, Croatia,

Ireland, and Portugal.

The throne of the HRE was continuously occupied by

the Habsburgs between 1438 and 1740.

The most powerful Habsburg of all was Charles V.

Under Charles, the Habsburg dynasty

achieved the position of being a true world power.

Charles was unhappy that there were holes separating his

various territories. It was his ambition to see an

unbroken empire across the continent. He came close. Charles stretched the House of Habsburg so far across Europe

that he was said to rule "the empire on which the sun never

sets".

Charles V was best known for his constant battles with the

Ottoman Empire (Turkey), but in his spare time as Holy Roman

Emperor, Charles was also the man who organized the initial

counter-attack to the Protestant Reformation.

However, it would be left to Ferdinand, brother of

Charles V, who caused the greatest war in European

history to date.

The Thirty Years War (1618-48) began when Holy Roman

Emperor Ferdinand II of Bohemia attempted to curtail

the religious activities of his subjects.

One needs to remember the duty of the Holy Roman Emperor is

to protect the Catholic Church. Ferdinand II assumed

he had the right to tell his people which religion they

should choose "or else".

This of course sparked rebellion among the Protestants of

the realm.

During the 16th century, the Reformation and the Counter

Reformation had divided all of Germany into hostile Protestant and

Catholic camps, each prepared to seek foreign support to

guarantee its integrity if need arose. Well, the need

arose.

In 1618, when Ferdinand II used his authority as the

Holy Roman Emperor to curtail certain

religious privileges enjoyed by his subjects, they

immediately appealed for aid to Protestants in the rest

of the empire and to the leading foreign Protestant states:

Great Britain, the Dutch Republic, and

Denmark.

Ferdinand now called upon the German Catholics (led

by Bavaria), Spain, and the papacy to send

armies in support.

Not surprisingly,

Ferdinand's coalition known as the Imperial Army

dominated Phase I and Phase II of the ensuing war.

Ferdinand and his allies won a major victory at White

Mountain (1620) outside Prague thanks to the Imperial armies

commanded by Albrecht von

Wallenstein. This victory was so complete that let

to the extirpation (extinction)

of Protestantism in most of the Hapsburg lands (Austria,

Bohemia).

Encouraged by his success, Ferdinand turned in 1621 against

Bohemia’s Protestant supporters in Germany. Despite aid from

Britain, Denmark, and the Dutch Republic, the Protestants lost

again.

In 1629, imperial armies commanded by Albrecht von

Wallenstein, a brilliant Bohemian military leader, overran

most of Protestant Germany and much of Denmark.

Ferdinand assumed he had won. He then issued the Edict of Restitution,

reclaiming lands in the empire belonging to the Catholic

Church that had been acquired and secularized by Protestant

rulers.

One of the interesting stories throughout the war involved

Wallenstein. This talented general had never

been defeated in a major battle. However he was

released from service in August 1630 after Ferdinand grew

wary of his ambition.

Immediately the Protestants began to win. Several

Protestant victories over Catholic armies induced Ferdinand

to recall Wallenstein, who again turned the war in

favor of the Imperial cause.

However, Emperor Ferdinand dismissed him for the second time out of

fear that Wallenstein was becoming too powerful.

Dissatisfied with the Emperor's treatment, Wallenstein

considered allying with the Protestants. However, he

was assassinated at Cheb in Bohemia by one of the

army's officials, Walter Devereux, acting with Emperor

Ferdinand's approval.

Had Wallenstein lived, Europe's map might look very

different today. Instead, with Wallenstein out

of the picture, the Protestants made a comeback.

It took Swedish military aid to save the Protestant cause.

In 1630 an army led by Gustavus Adolphus landed

in Germany.

Thanks to a subsidy from the French

government and assistance from many German Protestant

states, Adolphus routed the Imperialists at Breitenfeld

(1631) and drove them from Germany.

The Protestant revival continued until 1634. A Spanish

army raised by the Habsburgs intervened at Nordlingen to defeat the main

Swedish army and force the Protestants out of southern

Germany.

This new Hapsburg success had an unexpected consequence.

France had played only a support role till now. But

the growing power of the Habsburg family created a fear of

encirclement - Spain, Austria, and Germany were threats.

It was time to ensure that Germany stayed out of Habsburg

hands

France declared war first on Habsburg Spain (1635) and then

on Ferdinand, the Habsburg HRE emperor (1636).

Previously the war had been fought principally by German

states with foreign assistance throughout the 1620s.

With the entrance of France, now this war escalated to

become a struggle among the great powers - Sweden, France,

Spain, and Austria. Suddenly major campaigns involving

countless thousands of troops were fought largely on German soil.

What had started out as a localized battle suddenly became

the most brutal and all-encompassing war Europe had ever

seen.

For the next 12 years, 500 armies

maneuvered for supremacy in every corner of German

territory.

These armies carried out a

“dirty war”. The destruction caused by mercenary

soldiers defied description. Even if something wasn't valuable to them,

they destroyed it anyway if it might be of possible use to the enemy.

Horrible atrocities were committed

that came close to being flat out genocide.

For example, in Protestant Magdeburg, once the Imperial soldiers broke through

after a long siege, they lost

control.

The invading soldiers had not received payment for their

service. Now they took the chance to loot everything in sight;

they demanded valuables from every household that they

encountered.

Otto von Guericke, an inhabitant of Magdeburg, claimed that

when civilians ran out of things to give the soldiers, "the

misery really began. For then the soldiers began to beat,

frighten, and threaten to shoot, skewer, or hang the

people."

The attackers set fire to the city and started to massacre the inhabitants.

It took only one day for all of this destruction and death

to transpire. Of the 30,000 citizens, only 5,000 survived.

Eventually the war came to end. It was France's

intervention that brought things back under control.

France’s victory over the Spaniards at

Rocroi

(1643) and Sweden’s defeat of the Imperialists at Jankau

(1645) forced the Hapsburgs to make concessions that led to

the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.

What had started as a religious war ended as a war between

states.

The Habsburgs were well on their way

to victory till Roman Catholic

France and Orthodox Catholic Russia intervened. So much for

religious differences.

The irony was obvious. What had started as

a war of religion ended as a World War where religion no

longer mattered.

If anything good came of the Thirty Years War, it was

that people became much more accepting of religious

differences. What a shame it was that 7 million people

had to die so the living could figure it out.

Along the way, the Holy Roman Empire lost much of what

remained of its power. It would never again be a

significant actor on the international stage again.

The Habsburgs would continue to be crowned kings and emperors, but

their strength would derive from their family holdings, not

as leaders of the HRE.

|

Map of the Habsburg Family Dynasty. This is "the

empire on which the sun never sets."

Holy

Roman Emperor Ferdinand II, responsible for sparking a war

that killed 7.5 million people, most of whom were civilians.

Albrecht von Wallenstein

The

Massacre of Magdeburg in 1630 convinced many Protestant

rulers in the Holy Roman Empire to join Sweden's Adolphus

and take a stand against the Catholic emperor.

It

also printed on Protestant minds the indelible conviction

that Catholicism was a bloody and treacherous religion.

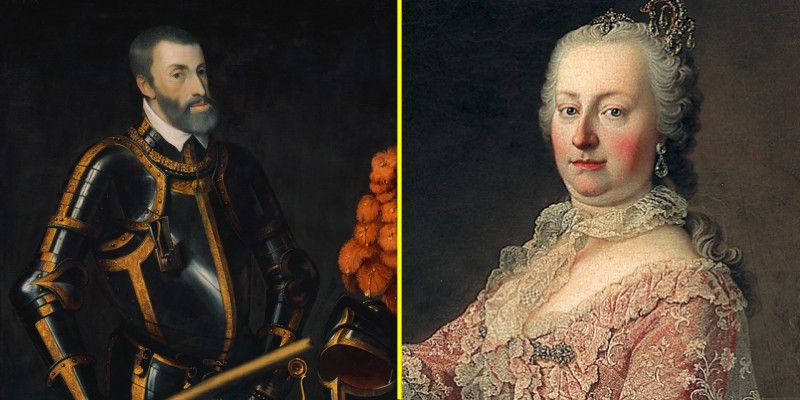

Charles V and Maria Theresa.

The secret weapon of

the Habsburg Family was their uncanny knack to have members

intermarry into other royal houses in order to build

alliances and inherit territory. Empress Maria Theresa is

recognized quite notably for it; she is referred to as the

"Great-Grandmother of Europe". For example, Marie

Antoinette was the fifteenth of sixteen children of Holy

Roman Empress Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis I.

The political side of the Habsburg dynasty ended with World

War I. However the family itself came to an end in a very

strange way. The Habsburgs sought to consolidate their

power by the use of frequent marriages within their own

family. Marriages between first cousins, or between uncles

and nieces, were commonplace in the family. If one married

"inside the family", one did not have to divide and share

the land with another family.

This

tactic was successful in keeping the vast lands to

themselves, but it backfired in a strange way.

Over time this practice resulted in a cumulatively

deleterious effect on their gene pool. A study of 3,000

family members over 16 generations suggests that inbreeding

led directly to their extinction. The gene pool eventually

became so small that the last of the Spanish line Charles

II, who was severely disabled from birth, perhaps by genetic

disorders, possessed a genome comparable to that of a child

born to a brother and sister, as did his father, likely due

to "remote inbreeding".

|

The 1648 Peace of Westphalia largely settled German affairs

for the next two centuries. It ended religious conflicts

between the states and included official recognition of

Calvinism.

The document altered the boundaries of the HRE by

recognizing Switzerland and the Netherlands had become

sovereign states outside the empire.

Germany itself was absolutely devastated. This war constituted the

worst catastrophe ever to afflict Germany to date.

Anywhere from 25%

to 40% of the overall population in the area was dead.

Half the men in Germany were dead. It would take a century

to replace the fallen.

The scorched earth policies had leveled entire villages. Castles were destroyed,

cities were ruined, farmlands and forests had been burned to

the ground.

Germany's economy was severely disrupted by the ravages of

the Thirty Years' War. The war created an economic decline

as the European economy shifted westward to the Atlantic states

- France, England, Spain, Netherlands and Belgium.

Germany had been disunited throughout its history, but it

had at least been prosperous. Its people were

industrious and diligent. Using its location at the center of Europe

and the Baltic Sea, the Germans had been leaders for

centuries in the Hanseatic League, a vitally important

commercial confederation.

That was all over. The shift in trade meant that

Germany was no longer located at the center of European

commerce but rather on its fringes. The Hansa towns in the

north became completely dominated by the Dutch.

The thriving economies of many German towns in the late

Middle Ages gradually dried up thanks to the long war. Germany

would now enter a long

period of economic stagnation that would extend over the

next two

hundred years.

The real change in Germany was the loss of morale. For

30 years, German states had waged war on other German states

in what amounted to a German "Civil War". Germans had

fought Germans. The country had been ripped asunder by

religious insanity.

Countless Germans had

been murdered by his fellow man all in the name of God.

Now the hatred and distrust of fellow Germans was intense.

Germany was split into 300 jigsaw pieces. There was no

recognized leader to pick up the pieces and put Germany back together again.

Ferdinand II, the man

who had caused this plague to begin with, had died in the

middle of the war. Ferdinand III, his son, took his place and made things even

worse. In 1644 during the last stage of the war, Ferdinand III gave the right to rulers of German states

to conduct their own foreign policy.

The emperor was trying to gain more allies in the

negotiations with France and Sweden, but this edict

backfired.

The

main result was the

division of Germany into even more territories —

all of which, despite their membership in the HRE,

won actual sovereignty.

The Holy Roman Empire concept was reduced to ashes. As

if it were possible,

Germany was less united at the end of the war than at the

start.

In a sense, 300 separate countries occupied the space we now call

Germany.

These weren't "colonies" like here in America that had

at least some common association. These 300 countries

all had their own flag, their own hereditary leader, and no

desire at all to be a part of anything bigger.

The survivors just wanted to retreat inside their borders and be

left alone to lick their wounds.

How could anyone ever possibly hope to unite a land as

disorganized as Germany?

|

This

map drawn at the end of the Thirty Years War gives another

look at the preposterous patchwork carpet of territories Germany had turned into.

The big winners

of the long war were Switzerland and Netherlands which broke

away from the HRE to become independent nations.

Is

this the strangest map ever? After the Thirty

Years War, the European continent resembled a giant doughnut

with divided Germany forming the massive pockmarked hole in the middle.

So what does this picture mean?

Saxony, Bavaria, and Brandenburg were the only sizeable

areas. In addition, there were roughly 300

small political units inside that Black Hole. Each

unit had its own leader and army. Each unit was strong

enough to withstand each other, but there was no one to

unite the 300 armies against a much larger common enemy.

Austria on the other hand was eying German territory

covetously. And so was somebody else...

|

|