Prussia, the New Kid

on the Block

|

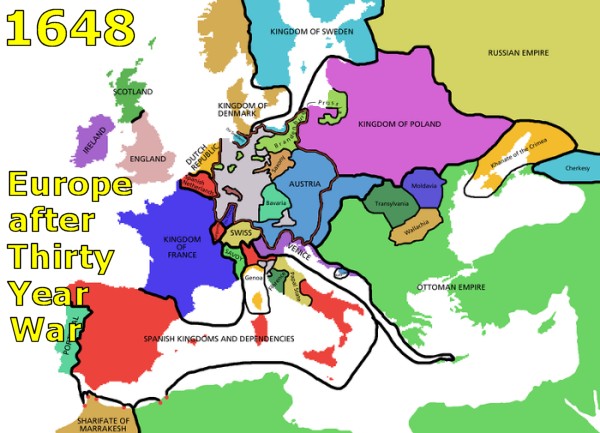

At the conclusion of the Thirty Years War, a new player in

the European Theater appeared. Its name was Prussia.

Now how can a new power appear out of nowhere?

Prussia had been there all along, slowly building steam

over the centuries.

The Thirty Years War was the catalyst that opened the door

for this middle of the road power to emerge as a superpower.

This story begins with the Hohenzollerns, a dynastic

family very similar to the Habsburgs. It

is an interesting story because it is a classic example of

how Europe operated in the Middle Ages.

This German family deliberately went

about acquiring various small political units. Over

time, the family parlayed

them into a vast empire that would someday become the nation

of Germany.

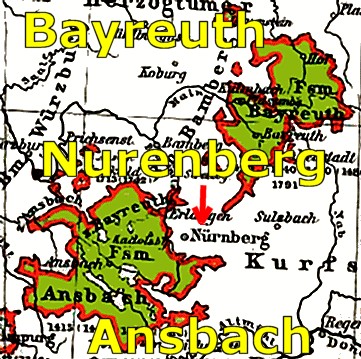

The Hohenzollerns got their start in the

Burgraviate of Nuremberg, a state of the Holy Roman

Empire from the early 12th to the late 15th centuries.

Nuremberg flourished due to its central location.

It became one great trade centers on the route from Italy to

Northern Europe.

Count Frederick III of Zollern was a loyal retainer

of the Holy Roman Emperors Frederick Barbarossa and

Henry VI. In 1185 Count Frederick married

Sophia of Raabs, the daughter of Conrad II, Burgrave of

Nuremberg (Burgrave:

hereditary ruler of a German town).

When Conrad II died in 1192, he left no male heirs.

Frederick III, husband to Conrad's daughter, was

granted the burgraviate of Nuremberg. He became Burgrave Frederick I

of Nuremberg-Zollern. At this point the family name changed

to

Hohenzollern.

|

1192 in

Nuremberg will be our starting point for the

advance of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

After

Frederick's death, his two sons partitioned the

family lands between themselves.

|

•

The older brother,

Frederick IV, received the county of Zollern and burgraviate

of Nuremberg in 1200 from his father, thereby founding the

Swabian branch of the House of Hohenzollerns. The Swabian

line remained Catholic and would fade into mediocrity,

Meanwhile

his brother's Franconian line would flourish.

•

The younger brother,

Conrad III, received the burgraviate of Nuremberg from

his older brother Frederick IV in 1218, thereby founding the

Franconian branch of the House of Hohenzollern. The

Franconian line would later convert to Protestantism.

Emperor Frederick II wished to develop Nuremberg to a

dependable base. Therefore in 1219 he bestowed a great

charter of freedom upon the castle market. While Conrad took

over the military protection of the town as a Burgrave, the

citizens were able to attain an increasing autonomy in their

internal affairs.

During his reign, Conrad would acquire the Rangau with

Ansbach, significant parts of the Pegnitz valley and

gained control over the most important trade routes to

Nuremberg. He successfully fought against the

marauding knights and warded off the nobility.

•

Frederick III of

Nuremberg (1220-1297) was the next Hohenzollern Burgrave of

Nuremberg

In 1248 he received from the Counts of Andechs the region of

Bayreuth by a so-called Meran's inheritance.

In 1273 Frederick III gave his deciding vote for his friend Rudolf of

Habsburg on the election to the king of the Romans. As a

reward, the King confirmed his position as a Burgrave and

granted the rank of a Prince-Elector. At this time,

Wunsiedel, Erlangen and Arzberg came into the possession of

the House of Hohenzollern.

This was important. Frederick III had just become one of

the Princes of Germany who were involved in electing the

King.

•

Frederick IV

(1287–1332) was notable for purchasing the town of Ansbach

(1331), nucleus of the later Hohenzollern Principality of

Ansbach established in 1398.

•

Frederick V

(1333–1338) acquired the principality of Bayreuth.

•

John II

(1309-1357) acquisition of the county of Kulmbach.

He purchased the contract of inheritance which became

effective with the extinction of the present owners.

•

Frederick VI

(1371–1440) became the first member of the House of

Hohenzollern to rule the Margraviate of Brandenburg,

one of the three most important duchies in the German area.

|

Hohenzollern Castle, ancestral home of the Hohenzollern

family

Nuremburg was a town when the Hohenzollerns got their start.

It would eventually become a major city in south central

Germany.

Today's

Rhine-Main-Danube canal runs through the center of town.

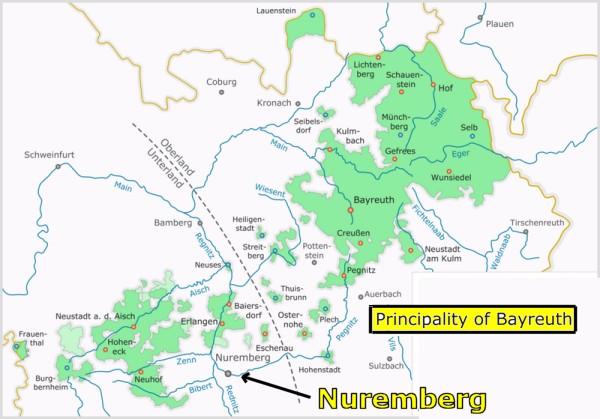

Nuremburg and Bayreuth. The Hohenzollerns are off to a good

start.

Brandenburg did not yet belong to the Hohenzollerns, but in

1411 they began governing this important territory.

|

So how did

Frederick VI get this promotion?

Keep in mind that the King of Germany was an elected

position. The Hohenzollern family was one of the seven

Prince Electorates who made the decision who would be the

next king.

Early in his

career,

Frederick VI made a important friend in Sigismund, King of

Hungary, when he fought in a major campaign.

|

Frederick VI |

In 1410, the death of Rupert, King of the Germans,

left the throne of the Holy Roman Empire vacant.

Sigismund enlisted Frederick's help in obtaining the

throne.

At the time, Jobst of Moravia ruled Brandenburg.

Therefore Jobst was one of the 7 prince-electors who had the right to

vote for the new emperor. Jobst opposed Sigismund's

election to be king.

Jobst's death under suspicious circumstances in 1411 cleared

the way for Sigismund's recovery of Brandenburg. Sigismund

enjoyed an

undisputed election as king of the empire later that year.

In gratitude for Frederick's services, King Sigismund

immediately made

him governor of Brandenburg.

Frederick fought with an iron hand against the rebellious nobility of the

March of Brandenburg (in particular, the Quitzow family).

In the end, he restored security.

Frederick was

rewarded for taming this important territory.

In 1415, King Sigismund granted Frederick the titles of

Margrave and Prince-elector of Brandenburg. On 21 October

1415 the Brandenburg states meeting in a Landtag asked

Frederick to rule in Berlin. The king awarded him the formal

enfeoffment of the margravate on 18 April 1417.

(enfeoffment:

deed by which a person is given land in exchange for a

pledge of service).

Brandenburg was a giant acquisition for the

Hohenzollern family. Brandenburg was one of the

premier duchies in the Kingdom of Germany.

The Hohenzollerns had started small in Nuremburg back in

1192. Now with the acquisition of Brandenburg in 1417,

the Hohenzollern family had definitely reached the big

leagues.

|

|

|

|

|

Old

Prussia and the Teutonic Knights

|

The Teutonic Knights were a German medieval military order

that was involved in the Holy Land Crusades. It was

formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to the Holy

Land by establishing way stations and hospitals. The military membership was

always small, with volunteers and mercenaries augmenting the

force as needed.

The Third Crusade (1189–1192), also known as the Kings'

Crusade, was an attempt by European leaders to reconquer the

Holy Land from Saladin. The Third Crusade featured an

all-star lineup which included the German Emperor

Frederick Barbarossa, King Richard I the

Lionheart of England, and King Philip II of France as

well as the Teutonic Knights.

The campaign was largely successful, capturing Acre, Jaffa,

and reversing most of Saladin's conquests. However, it

failed to capture Jerusalem, which was the emotional and

spiritual fixation of the Crusade.

After the Crusade concluded, the Teutonic Knights needed

something to do. At the time, Konrad of Masovia

(Poland) was busy trying to conquer adjacent pagan lands in

Prussia, an area in the Eastern Baltic.

Unfortunately, Konrad wasn't doing very well.

At the invitation of Konrad and with the blessings of the

Holy Roman Emperor, the military order began a Northern

Crusade in 1230. Konrad and the Teutonic

Knights launched a joint invasion of Prussia intended to

Christianize the Baltic Old Prussians. The Teutonic Knights

were encouraged by the Emperor's whispered suggestion that

they could keep whatever

they conquered.

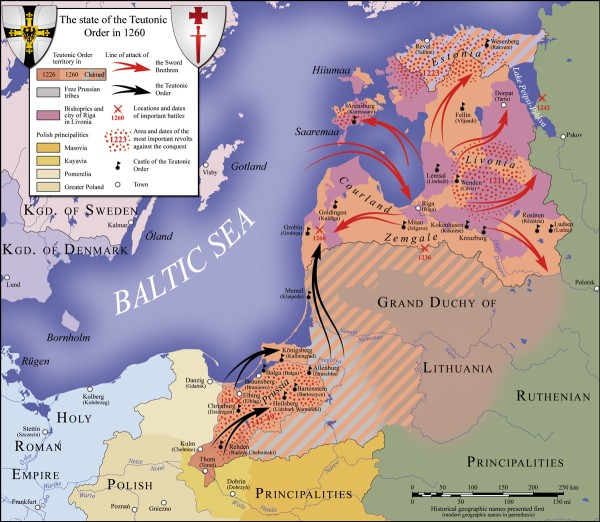

To make a long 50 year story short, the Teutonic Knights were

spectacularly successful. After conquering the area

known as Prussia (see map), they told Konrad of Masovia to

go take a hike, then settled down in their new territory.

Over the next 30 years (1230-1260), the Knights continued to

expand their territory to the north, conquering areas such

as Lithuania, Livonia (Latvia), and Estonia.

Then the Knights spent the next 20 years subduing the

populace and bending them to their will and ways.

Fighting between the Knights and the Prussians was

ferocious. The conquest of Prussia was accomplished

only with much bloodshed. It was spread out over more than

50 years during which native Prussians who remained unbaptised were subjugated, killed, or exiled.

After 50 years of warfare and brutal conquest, the end

result meant that most of the Prussian natives were either

killed or were deported. With the population

decimated, the Teutonic Order

encouraged the immigration of colonists from the Holy Roman

Empire of the German Nation (mostly Germans, Flemish, and

Dutch). The colonists included nobles, burghers, and

peasants. Any surviving "Old Prussians" were gradually

assimilated through a process called "Germanization".

Unfortunately the brutal Teutonic Knights were better at

fighting than creating civilization. They never made

any real attempts to use diplomacy to create peace in the

area.

Poland hated them, Russia hated them, Lithuania hated them,

and their own citizens hated them. A series of

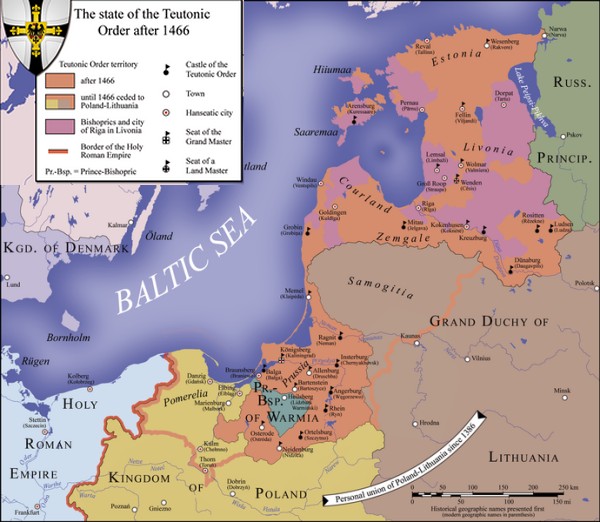

counter-attacks began. After the high point of 1260, each

future war over the next two centuries cost them large

chunks of territory.

Keep in mind that these were military men. They were

better at killing than building. They ruled through

force, not through politics and compromise. As the

economic fortunes of their area declined, the Knights had

trouble paying their bills and hiring new mercenaries to do

their fighting.

The Prussian Confederation was an organization formed

in 1440 by a group of 53 nobles and clergy and 19 cities in

Prussia to oppose the heavy taxation and poor leadership of

the Teutonic Knights. The revolt of the Prussian

Confederation in 1454 enticed Poland to join the battle

on their side.

This began the Thirteen Years War (1454–1466).

The Teutonic Knights were the losers, the Poles were the

winners. Under the terms of the peace treaty, the

Poles received extensive territory.

Forty years later, Sigismund I (1467-1548) became King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1506. Sigismund would

play a key role in the fortunes of Europe by

strengthening the Habsburgs as well as the

Hohenzollerns during his reign. Any study of the

Prussian-Austrian rivalry in the 1800s has to include this

chapter.

Sigismund was having trouble enforcing the terms of 1466

peace treaty. The Teutonic Knights had been in a long power

struggle with Poland over Prussia and now they were

threatening another war to regain the lands lost in

1466. Sigismund knew the Teutonic Knights answered to

only one authority, the Holy Roman Emperor. So

Sigismund swung a deal with HRE Emperor Maximilian.

In return for Maximilian keeping the Teutonic Knights in

line, Sigismund consented to the marriage of the children of

Vladislaus II of Bohemia and Hungary, his brother, to the

grandchildren of Maximilian, a Habsburg. Through this

double marriage contract, Bohemia and Hungary would pass to

the House of Habsburg in 1526, on the death of Sigismund's

nephew, Louis II. This was a huge break for the

Habsburg dynasty.

Sure enough,

Sigismund regretted the deal from the moment he made it.

He was deeply worried about the growing ties between the

Habsburgs and Russia, Poland's worst natural enemy.

Meanwhile the Teutonic Knights' fortunes had steadily

declined throughout the 15th century. They in turn hoped

that by selecting a new leader connected by marriage to the

ruling dynasty of Poland, they would strengthen their

bargaining position and be able to get their lands back by

diplomacy rather than war.

In 1511 the Teutonic Knights turned to Albert

(1490-1568), a member of the Brandenburg-Ansbach branch of

the House of Hohenzollern to become their new Grand Master.

Albert's election as Grand Master worked wonders. He

was a skilled political administrator and leader.

Albert did

indeed reverse the decline of the Teutonic Order.

Albert of Hohenzollern had been chosen specifically in the

hope that his relationship to his maternal uncle, Sigismund, Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland, would

facilitate a settlement of the disputes over eastern

Prussia.

Albert, the new Grand Master, was completely loyal to his

duties to the HRE and to the papacy. Albert defied his

uncle Sigismund and refused to

submit to the crown of Poland.

In 1519, Poland declared war. The Teutonic-Polish war

went back and forth with neither side able to get an

advantage.

Then something strange happened. In 1521, the

Ottoman Empire invaded Bohemia. This was precious Habsburg

territory!!The new Holy Roman Emperor,

Charles V, a Habsburg, demanded that the Teutonic

Knights and Poles stop their hostilities and aid him instead

in the defense

of Europe against the infidels.

Both sides were Roman Catholic and theoretically under the

control of the HRE. Moreover they were both tired of a war

that neither side was winning, so they agreed to an

armistice.

Then something even stranger happened. During the

four-year truce, the Polish-Teutonic dispute had been referred to Emperor

Charles V and other princes, but no settlement was reached.

Albert continued his efforts to obtain help in view of the

inevitable end of the truce. About this time, Albert

realized he was very interested in this new Lutheran

religion. Eventually, in Wittenberg, Albert met none

other than Martin Luther himself.

Luther had a

stunning idea. He suggested that Albert abandon the rules of

his corrupt Teutonic Order. Then he should convert Prussia into a

hereditary duchy for himself, and make Prussia Protestant!!

Finally, Albert should marry and consolidate Prussia with

the powerful Brandenburg nation-state.

Once Albert was able to wrap his mind around the idea, he

agreed it made sense. He resigned as Grand Master and

converted to Lutheranism in 1525. He then assumed the

Prussian Homage from his uncle Sigismund I the Old,

King of Poland.

In return, Albert would receive the hereditary rights to the

now-secularized Duchy of Prussia as a vassal of the Polish

Crown.

Since the Teutonic Knights had worn out their welcome ages

ago, everyone back in Prussia supported the move (other than

the Knights, of course). The Prussian diet embraced

both the new Duke and Protestant Reformation to Lutheran

faith.

The betrayal by Albert caught the Teutonic Order completely

by surprise. It was a bloodless coup. Thanks to

the clever suggestion of the crafty Martin Luther, Albert

was able to oust the Teutonic Order without a war. To

raise even a sword invited the invasion of Poland as well as

a mass uprising of their own people against them. It

was truly a master stroke.

The Teutonic Order quickly

elected a new Grand Master who tried to fight the loss of

power in the Prussian territories by political means, but it

didn't do any good. They

never regained influence.

The new arrangement was confirmed by the Treaty of Kraków

in 1525. Albert pledged a personal oath to his uncle King

Sigismund. In return he was invested with the duchy for himself and

his heirs.

|

1260:

Highwater mark for Teutonic Knights. Oddly enough, as

the map shows, this territory is not adjacent to the vast

Holy Empire. Poland is inconveniently in the middle.

This would have interesting consequences 400 years later in

1701.

1466:

Teutonic Knights have just lost the 13 Years War to Poland.

Their territory is shrinking, their power is in decline.

The Knights have many enemies and no allies other than the

Holy Roman Emperor. This explains why they turned to

"diplomacy" instead of their usual aggressive policies.

Polish

King Sigismund

Albert, a member of the Brandenburg-Ansbach Hohenzollerns,

the man who became the first Duke of Prussia .

The

Prussian Homage, 1525.

Here

Albert is pledging loyalty to his uncle King Sigismund of

Poland. In return, he becomes the first Duke of

Prussia. Prussia now becomes an ally and vassal state

to Poland.

Albert's stunning betrayal of the Teutonic Knights, his

employers, paved the way for the rise of Prussia, the rise

of Hohenzollerns, and would open the door for Germany's

Unification 300 years from now.

|

It was win-win for both sides.

In return for Albert's

help in getting rid of the hated Teutonic Knights, Sigismund

had just handed the Hohenzollern family the keys to the

entire Kingdom of Prussia!!

Albert's incredible move to obtain the Duchy of Prussia

would pave the way for the rise of the House of

Hohenzollern. Furthermore, due to his renunciation of

the Teutonic Order, Albert could now marry and produce legitimate

heirs... which he did.

Albert is therefore seen as the father of the Prussian

nation. He was indirectly responsible for the eventual

unification of Germany.

|

|

|

|

Brandenburg-Prussia

|

Brandenburg-Prussia was the term used for the Brandenburgian Hohenzollern

dynasty between 1618 and 1701.

After Albert's bold move to become the First Duke of Prussia

in the 1525, the connection between the Brandenburg

and Prussian territories was one of distant

relatives. The Hohenzollern family had grown so large

there was one line ruling in Brandenburg and another line

ruling in Prussia.

It would take two more generations to bring the two

territories under one roof. Anna,

granddaughter of Albert I and daughter of Prussian Duke

Albert Frederick (reigned 1568–1618), married her cousin

Prince Elector John Sigismund of Brandenburg.

This union paid immediate dividends. One immediate benefit of the

familial intermarriage between Anna and John Sigismund came the

Treaty of Xanten.

A dispute was settled in the

Lower Rhine town of Xanten in 1614 between Wolfgang William,

Duke of Palatinate-Neuburg and John Sigismund,

Elector of Brandenburg, with representatives from England

and France serving as mediators.

The Treaty of Xanten ended the hostilities between Wolfgang William

and John Sigismund. Based on the terms of the treaty,

Wolfgang William received Jülich-Berg and Ravenstein.

In return, John Sigismund received the territories of

•

Cleves-Mark

•

Ravensberg

These

territories were the first provinces at the Rhine and in

Westphalia to be governed by the Hohenzollerns. They would

become the oldest constituents of the future Prussian

Rhineland and the future Province of Westphalia.

This was a prime example of how the Hohenzollerns were slowly

putting the German jigsaw puzzle together.

Upon the death of Albert Frederick in 1618, who died without

male heirs, John Sigismund was granted the right of

succession to the Duchy of Prussia through Anna.

The next step had been in the planning for two generations.

The Prussian line of the family died off without a male heir

in 1618. No problem. The main branch of the

Hohenzollern family had been intermarrying with the branch

ruling the Duchy of Prussia for the past 100 years.

The death of Albert Frederick allowed John Sigismund representing the main

branch to secure succession in Prussia upon the extinction

in the male line in 1618.

From this time on, the Duchy of Prussia was now in personal union

with the Margraviate of Brandenburg.

From this point on, the Elector of Brandenburg and

the Duke of Prussia would be the same person.

The resulting state,

known as Brandenburg-Prussia, consisted of

geographically disconnected territories in Prussia,

Brandenburg, and the Rhineland lands of Cleves and Mark

(see map).

The House of Hohenzollern was definitely on the rise.

One by one, various territories were coming under

Hohenzollern control.

1618 also marked the start of the Thirty Years

War.

Depending on one's point of view, the Thirty Years War was

both devastating and incredibly helpful to the

Hohenzollerns.

The Duchy of Brandenburg (which roughly correlates to

East Germany and Berlin from the Cold War era) was the scene of much of

the fighting. Both the Protestants and Roman Catholics

wanted control of this valuable property. As a result

Protestant and Catholic armies swept the land back and

forth.

The Elector would change hands three times,

there was brutal killing, burning, seizing men and taking

the food supplies. Upwards of half the population was dead

or dislocated. Berlin and the other major cities were

in ruins. Recovery would take decades.

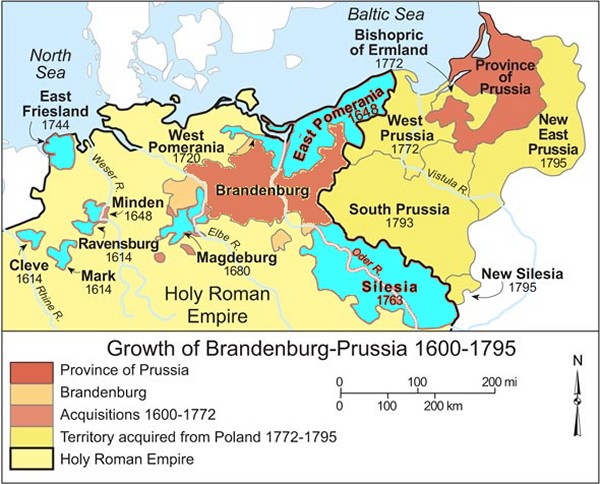

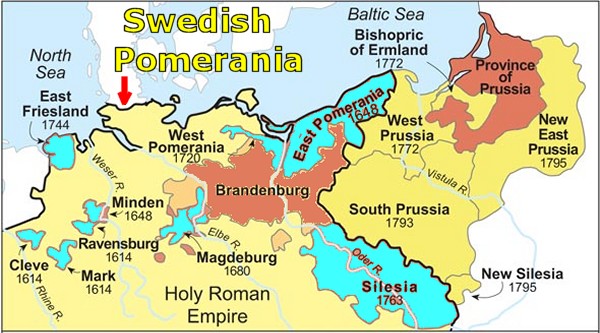

On the other hand, the 1648 Peace of Westphalia which

ended the Thirty Years' War brought four new territories

under Hohenzollern control. Brandenburg

gains in 1648:

•

Minden (1648)

•

Halberstadt (1648)

•

East Pomerania (incorporated in 1653)

•

Duchy

of Magdeburg (incorporated in 1680).

These acquisitions during the second half of the 17th century laid the basis for

Prussia to become one of the great players in European

politics later on.

Another major factor in Prussia's rise was Frederick William

(1620-1688). Frederick William became the Elector of

Brandenburg (and Prussia as well) in 1640 near the end of

the Thirty Years War. He was an extremely

talented man.

It was Frederick William's job to get the devastated

Brandenburg back on its feet at the conclusion of the war.

|

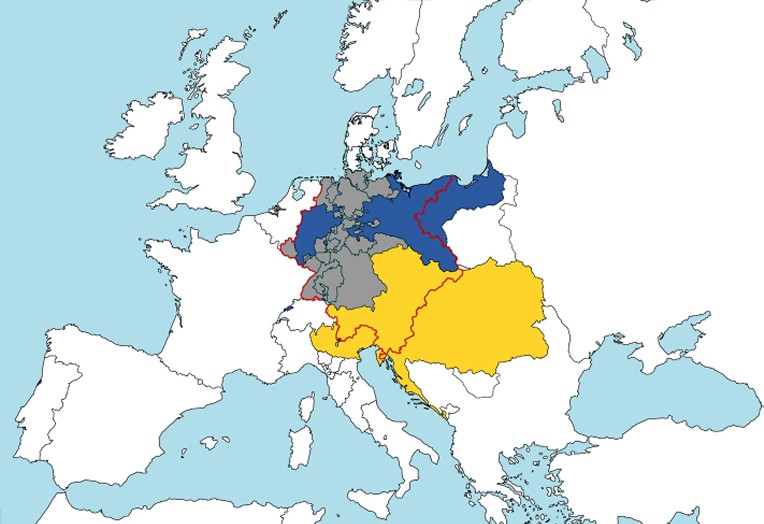

If one

looks carefully, the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of

Brandenburg can be seen bordering the giant Kingdom of

Poland.

Meanwhile, "Germany" is nearly a complete vacuum occupied by

300 or so separate nation-states too small to be seen on the

map.

John

Sigismund

(1523-1619), Prince-Elector of Brandenburg and the eighth

Hohenzollern to rule over Prussia, but the first of his line

to rule over Brandenburg and Prussia simultaneously.

This

map shows how widely scattered the Brandenburg-Prussia

holdings were. The properties stretched from the Rhine

to Russia. Berlin, the capital of Brandenburg, was 340

miles from Konigsberg, the capital of Prussia.

|

Frederick

William's first move was to

open Brandenburg to large-scale immigration of

mostly Protestant refugees from all across war-torn Europe.

This key maneuver helped to replenish the population

in Brandenburg much more quickly.

Frederick William,

known as "The Great Elector", took other measures as

well. He started to centralize

Brandenburg-Prussia's administration and reduce the

influence of the separate estates existing within its

borders. In other words, someone had

finally begun to consolidate the bits and pieces of Germany

rather than divide further.

Frederick

William was a military commander of wide renown, and

his standing army would later become the model for

the Prussian Army. He is notable for his joint

victory with Swedish forces at the Battle of Warsaw

(1656), which some say marked "the beginning of

Prussian military history",

The emerging Brandenburg-Prussian military potential,

based on the introduction of a standing army in 1653, was

further responsible for widely noted victories at Fehrbellin (1675) and the

Great Sleigh Drive (1678).

Frederick

William was skilled in more ways than simply

war. He saw the importance of trade and promoted it

vigorously. Indeed, his legacy is practically

flawless.

Everyone agrees

his military build-up combined with shrewd domestic

reforms gave Prussia a strong position in the

post-Westphalia political order of north-central

Europe, setting Prussia up for elevation from duchy

to kingdom.

|

|

|

|

|

Frederick I Prussia

|

Frederick I (1657-1713) was the son of Frederick

William.

Frederick succeeded his father in Prussia and Brandenburg

upon his father's death in 1688. He would be an

effective ruler, but his time was unusually quiet. Although

the Prussian army took part in several different campaigns

to assist allies, there were no significant territorial

gains during his 25 year reign.

Frederick was best known for a major upgrade in Prussian

status.

1701 was a big year for Prussia. His father's victory in Warsaw

back in 1656 had removed the "vassal" status. It meant

Prussia was no longer under the control of Poland. It

was now a free state able to

do whatever it wanted.

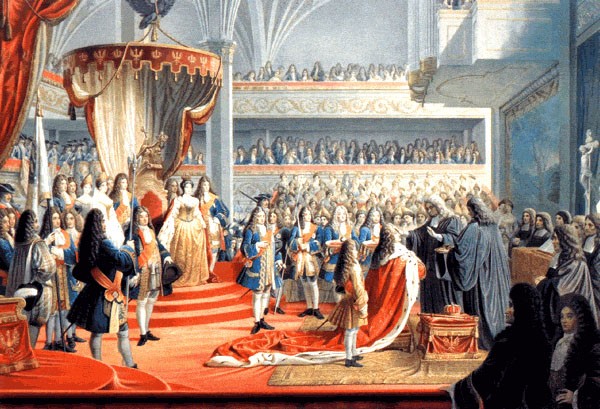

In 1701 Frederick I decided it was time to

take a step up. He wanted to declare himself King of

Prussia.

Technically speaking, this was a no-no. According to

Germanic law at that time, no kingdoms could exist within

the Holy Roman Empire, with the exception of the Kingdom of

Bohemia.

Frederick persuaded Leopold I, Archduke of Austria and Holy

Roman Emperor, to allow Prussia to be elevated to a kingdom.

Frederick's argued that since Prussia had never been part of

the empire and the Hohenzollerns were fully sovereign over

it, it could now be ruled as a "kingdom".

In return for Hohenzollern assistance in the War of the

Spanish Succession and support for the Habsburg

candidate in the subsequent election, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I

gave in to Frederick's request on one condition.

Leopold, a member of Habsburg family, would allow Frederick to crown himself "King in

Prussia", but not "King of Prussia".

Frederick smiled. Close enough. Deal.

The net result of Leopold's move weakened further the

authority of the emperor over the members of the Empire.

It compelled him to rely more and more upon his position as

ruler of the Austrian archduchies and of Hungary and

Bohemia.

As for Frederick, it marked the coming of age for the

Hohenzollern dynasty. The family was now stepping up

in class. Only the Habsburg family was more powerful.

As one can see, the paths of the Habsburgs and the

Hohenzollerns were crossing with increasingly regularity.

At this point, the Hohenzollerns were still loyal allies to

the Habsburgs, but that would soon change.

Prussia was on the move.

|

1701

Coronation of Frederick I in Prussia's Königsberg Castle.

|

Austrian-Prussian Rivalry

|

Under Louis IV, the fabled Sun King, France had become

the leading power of Europe in the 17th century until his

death in 1715. However, under Louis V and

Louis VI, France's power declined under weak leadership.

It is no coincidence that Prussia's rise to power was aided

by

France's decline. With France increasingly distracted

by the rising power of its arch-enemy England, this gave Prussia

a free hand to take on Austria over control of the Holy

Roman Empire.

Now the stage was set for

Austria and Prussia to begin its long-standing conflict and rivalry

for supremacy in Central Europe during the 18th and 19th

centuries.

With Austria corresponding to Habsburg control and Prussia

to Hohenzollern control, both families understood there were

two major prizes. The Polish

territories seemed vulnerable and the grand prize were the

300 independent German-speaking political states up for

grabs.

Which family and which country would get the lion's share?

This rivalry was termed German dualism in the German

language area.

While wars were seen as part of the rivalry, it was also a race

for prestige to be seen as the legitimate political force of

the German-speaking peoples.

The Habsburg family was watching with amazement and alarm at

the Hohenzollern progress. The Hohenzollerns were

gathering up small states at a regular clip. For

example, East Frisia, a small state located in the

northwest corner of Germany near Hamburg, willingly gave up

its independence to Prussia in 1744.

The region was taken over by Prussia after the last Cirksena

prince had died without issue. There was no resistance to

this takeover since Prussia promised to honor the

traditional autonomy of the Frisians. It had all been

arranged by contract beforehand.

The Prussians preferred to use money, respect and

negotiation wherever possible. However, they didn't

mind using their army as well. The Prussians were born

for military service. More than likely, the 300 years

of domination by the militaristic Teutonic Knights had left

an indelible stamp on the people.

After Frederick I came Frederick William (1713–1740),

a real nut case. Biographer Jerome Blum wrote this

about him:

Uncontrollably

violent in temper, vulgar in speech and manner, scornful

of education and culture, and so deeply pious that he

considered theaters "temples of Satan."

He made a fetish of

cleanliness, washing and grooming himself many times

each day.

At the the same

time, this royal neurotic was the most remarkable

reformer of his dynasty....He was the real father of

Prussian militarism and Prussian bureaucratic

efficiency.

Frederick William, the austere "Soldier

King", was the creator of the vaunted Prussian bureaucracy

and the professional standing army. Under his careful eye,

the Prussian military developed into one of the most

powerful fighting forces in Europe.

One statesman

commented on the size of the army in relation to the total

population by saying "Prussia is not a state with an army,

but rather an army with a state".

Frederick William participated in the Great Northern

War, a conflict between Sweden and Russia. He was

determined to gain the Oder estuary with its access to the

Baltic Sea for the Brandenburgian core areas, which had been

a state goal for centuries.

•

Frederick William

was rewarded for his efforts with the acquisition of Swedish

Pomerania in 1720.

Frederick William is noted for one other thing.

He was the father of Prussia's Frederick the Great.

Frederick William was determined to make his son

become a fine soldier. One never knows how to create genius in a child, but there

can be no doubt Frederick William used some very

strange techniques in raising his gifted child.

|

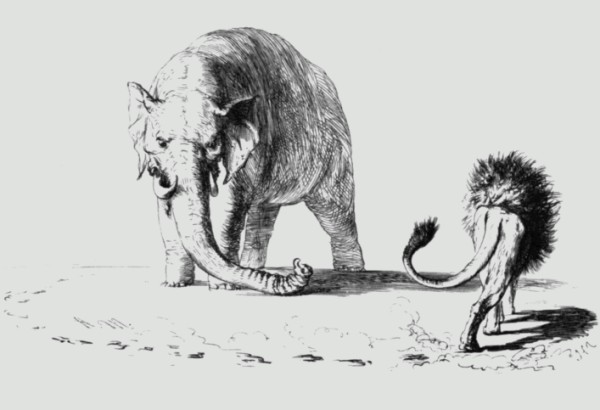

The

Prussian lion circles the wary Austrian elephant.

Frederick William (1713-1740).

His

son Frederick the Great would become one of the dominant

leaders of the Eighteenth Century.

Frederick William acquired Swedish Pomerania in 1720

|

As a small child, young Fritz was

awakened each morning by the firing of a cannon. At the age

of 6, Fritz was given his own regiment of children to drill

as cadets. One year later, Fritz was given a miniature

arsenal to play with.

Frederick William would frequently mistreat Fritz. The

father did this to force his son to learn how to be tough. Fritz

was beaten for being thrown off a bolting horse and for wearing

gloves in cold weather. Nothing like tough love,

right?

Not surprisingly, the child decided to rebel against his

harsh treatment. When the prince turned 18, he failed

in his attempt to flee to England with his tutor. The

livid king nearly executed his son for "desertion".

Eventually the father decided a better punishment would be

to force his son to watch the tutor be executed. Frederick

fainted on the spot at the horror of seeing his closest

friend decapitated.

Then the father had the prince court-martialed and thrown in

jail for good measure. Like we said, the man was a

serious nut case.

|

| |

Frederick the Great

|

Prince Frederick (1712-1786) was twenty-eight years

of age when his father Frederick William I died.

Frederick acceded to the throne of Prussia in 1740.

Frederick was an interesting figure. As a young man,

he was far more interested in music, arts and philosophy than he was

in world conquest. Perhaps he disdained the military

life due to his deep hatred of his cruel and authoritarian father.

For example, the works of Niccolò Machiavelli, such as

The Prince, were considered required reading for a

future king in Frederick's age. Frederick didn't care

much for Machiavelli. In 1739, Frederick

finished his Anti-Machiavel, an idealistic refutation

of Machiavelli's ideas. Frederick published his

thoughts anonymously in 1740, but Voltaire learned the truth

and distributed it in Amsterdam to great popularity.

Sadly, Frederick's years of dedication to the arts instead of

politics ended upon the 1740 death of Frederick William and

his inheritance of the Kingdom of Prussia.

That is when Frederick surprised everyone. Considering

he had just fashioned himself, the anti-Machiavelli, he

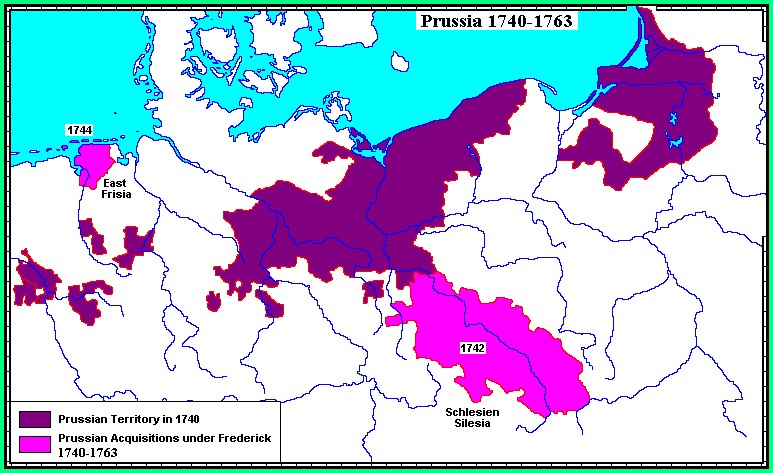

wasted no time attacking Silesia 5 months after taking power.

It was Frederick's goal to unite his disconnected lands.

With this in mind, Frederick fought wars mainly against

Austria, the power base of the Habsburg dynasty that had reigned

as Holy Roman Emperors almost continuously from the 15th

century until 1806. Frederick was fortunate to catch

Austria just as it had begun to decline. Frederick

would be able to establish Prussia as the fifth and smallest

European great power by using all the resources his strange

yet effective

father had developed.

|

|

Silesia was a prized possession of Austria, the

supposed ally of Prussia. Just two years earlier Prussia and Austria had been allies in the War

of Polish Succession (1733–1738). However, that

all changed Charles VI, the Holy Roman

Emperor, died on 20 October 1740. His

death meant his daughter Maria Theresa could conceivably

become not only the reigning queen of Austria, but perhaps

even the first female Holy Roman Emperor.

A woman on

the throne? All of Europe was in an uproar.

While the Austrian Habsburg Monarchy was distracted by the

firestorm of arguments over allowing "a woman" to take power, Frederick saw an

opportunity to invade Silesia, the mineral-rich property adjacent to

the border of Brandenburg.

This territory, today a part of Poland, was

located directly south of the Brandenburg.

Frederick feared that Poland was just as interested in

adding this plumb territory to their kingdom as he was.

Control of Silesia would unite Saxony and Poland

on Brandenburg's southern border.

Frederick wasn't about to let that happen. So he took

everyone by surprise and launched a preemptive strike.

Austria mounted a creditable defense. However, Austria

was forced to retreat in 1741 when France suddenly attacked

on a different front. It was later learned that

Frederick had made a secret pact with France to make this

exact move.

|

Silesia was coveted by Poland as a way to connect to Saxony.

Frederick simply beat Poland to the punch. Prussia

pretty much "owned" Silesia as early as 1741, but Austria

refused to give up trying to win the valuable territory back

until 1763.

|

Frederick may have been only 28, but he was off to quite a

start.

So what was going on here? The great powers of Europe

sensed the vast Austrian Empire was ripe for the pickings.

The Austrian Empire might have been large, but it was

overextended. Austria did not have enough armies to defend

all its territories.

Furthermore Maria Theresa was perceived as a weak woman

completely

incapable of inspiring her military or comprehending

strategy.

Frederick decided to test her immediately. By

coordinating with France

ahead of time to march on Austrian borders at a key point,

Frederick's trap worked like a charm. Austria was forced to recall

its armies from Silesia to defend Vienna instead. At

this point, Frederick had no trouble taking Silesia.

Prussia's attack on Silesia was part of a much larger

ongoing battle known as the War the Austrian Succession.

The Silesian Wars were a mere part of the larger

international conflict known as the "War of the Austrian

Succession" (1740-1748). It would take years of back and

forth fighting, but in the end Prussia prevailed and

retained its prize. Maria Theresa ceded Silesia to

Prussia in the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748).

The end of the war sparked the beginning of the German

dualism between Prussia and Austria, which would ultimately

fuel German nationalism and the drive to unify Germany as a

single entity.

In a curious footnote to history, Frederick had once

proposed asking Maria Theresa to marry him. It would

be interesting to know what she would have thought of this

match.

As it turned out, Maria Theresa developed a powerful dislike

for Frederick. She had been obsessed with regaining

Silesia, but Frederick had matched every one of her moves.

Here is an interesting letter sent from Count Podewils, the

Prussian ambassador in Austria, to Frederick the Great at

the conclusion of the Austrian Succession War.

"Maria

Theresa has, as you well know, a terrible hatred for

France, a nation with which it is most difficult for her

to keep on good terms.

However,

she controls this passion except when she thinks to her

advantage to display it.

She

detests Your Majesty, but acknowledges your ability.

She cannot forget the loss of Silesia, nor her grief

over the soldiers she lost in wars with you."

|

The

empress had a long reign which spanned 40 years. Some

historians have termed Maria Theresa as the savior of the

Habsburg Dynasty. Her efforts to transform her empire into a

modern state solidified the Habsburg rule. When she

came to the throne, her state appeared on the brink of

dismemberment. Maria Theresa provided a strong foundation

for the continuation of the Habsburg Dynasty into the modern

era.

|

1756-1763: Seven Years

War

|

The Seven Years War is sometimes described as the

first World War because all the great powers of Europe

squared off against each other and the United States of

America was involved as well.

|

Essentially the Seven Years War continued the growing

tensions between England and France as well as Prussia and

Austria.

Austria was still determined to get Silesia back.

Maria Theresa was able to form an imposing alliance of

France, Austria, Sweden, and Russia against Prussia. The

Russians and the Austrians were determined to reduce the

power of Prussia, the new threat on their doorstep.

Along with France, plans were made for a 1756 attack on

Prussia by Austria and Russia, subsidized by France.

Prussia's only real ally was England with its great navy,

but England could not help much in any battles fought on the

European continent. This meant it was basically

Prussia against the World.

|

|

In

many ways, Prussia reminds us of famous warrior states.

Every young man born in Prussia knew he was destined for the

military. In that way, Prussia was very much like

ancient Sparta. However, a better parallel might be modern-day Israel.

Like

Prussia, Israel is a small country surrounded on every side by

fierce enemies and overwhelming numbers. However,

despite being heavily outnumbered, Israel is greatly feared

thanks to its powerful military.

Another thing Prussia and Israel have in common is a lot of

guts. Neither country is afraid to gamble. For

example, in a move highly reminiscent of Israel's pre-emptive strike

on Egypt in the 1967 Six Days War, Frederick decided

his best move was to attack first.

1956

Knowing full well that neighboring countries were conspiring

against him, Frederick was determined to strike first. On 29

August 1756 Frederick's well-prepared army crossed the

frontier and preemptively invaded Saxony. He

faced widespread criticism for his attack on neutral Saxony

and for his forcible incorporation of the Saxony forces into

the Prussian army after his successful occupation.

1957

Frederick's successful campaign in Saxony once again

established himself as Europe's premier general and his men

as Europe's most accomplished soldiers. In spite of these

successes, the Prussians were now facing the prospect of

four major powers attacking on four fronts (France from the

West, Austria from the South, Russia from the East and

Sweden from the North). Meanwhile a combined force from a

number of smaller German states such as Bavaria had been

established under Austrian leadership, thus threatening

Prussian control of Saxony. Things were looking very grim

for Prussia at this time.

1958

By this point Frederick had grown increasingly concerned

about the Russian advance from the east and marched to

counter it. On 25 August 1758, at the Battle of Zorndorf

a Prussian army of 35,000 men under Frederick fought to a

standstill a Russian army of 43,000. Although both

sides suffered heavy casualties and the Russians withdrew

from the field in good order, Frederick claimed a victory.

In the undecided Battle of Tornow on 25 September, a

Swedish army repulsed six assaults by a Prussian army, but

did not push home an attempt to move on Berlin following the

Battle of Fehrbellin.

During this back and forth year, Prussia was clearly tiring

from being forced to battle on four fronts.

1759

The year 1759 saw some severe Prussian defeats. At the

Battle of Kay, the Russian Count Saltykov with 47,000

Russians defeated 26,000 Prussian troops commanded by

General Carl Heinrich von Wedel.

Though the Hanoverians (a Prussian ally) defeated an army of

60,000 French at Minden, Austrian general Daun forced the

surrender of an entire Prussian corps of 13,000 men in the

Battle of Maxen.

Frederick himself lost half his army in the Battle of

Kunersdorf, the worst defeat in his military career, and

one that drove him to the brink of abdication and suicide.

The disaster resulted partly from his misjudgment of the

Russians, who had already demonstrated their strength at

Zorndorf and at Gross-Jägersdorf.

1760

1760 brought even more disasters to the Prussians. The

Prussian general Fouqué was defeated in the Battle of

Landshut. The French captured Marburg, and the Swedes

part of Brandenburg-Prussian Pomerania.

The Hanoverians were victorious over the French at the

Battle of Warburg, their continued success preventing

France from sending troops to aid the Austrians against

Prussia in the east. Despite this the Austrians, under the

command of General Laudon captured Glatz (now Klodzko) in

Silesia.

In the Battle of Liegnitz Frederick scored a victory

despite being outnumbered three to one.

The Russians under General Saltykov and Austrians under

General Lacy briefly occupied his capital, Berlin, in

October. The end of that year saw Frederick once more

victorious, defeating the able Daun in the Battle of

Torgau, but he suffered heavy casualties and the

Austrians retreated in good order.

1761

Prussia began the 1761 campaign with just 100,000 available

troops, many of them new recruits.

The Russians under Zakhar Chernyshev and Pyotr Rumyantsev

stormed Kolberg in Pomerania, while the Austrians

captured Schweidnitz. The loss of Kolberg cost

Prussia its last port on the Baltic Sea. As the Prussian

armies had dwindled to just 60,000 men, Frederick's survival

was severely threatened.

|

January 1762 - The End

is Near

In Britain, it was speculated that a total Prussian collapse

was now imminent. Britain now threatened to withdraw

its subsidies if Prussia didn't seriously consider offering

to make concessions to secure peace.

Truth be told, Frederick had clearly bitten off more than he

could chew.

Facing a coalition which included Austria, France, Russia,

Saxony, Sweden and several minor German states, over the

next several years Frederick narrowly kept Prussia in the

war. By 1962, with his territories repeatedly invaded

on all sides, Frederick assumed that this was the end.

On 6 January 1762, Frederick wrote to Count von Finckenstein,

"We ought now

to think of preserving for my nephew, by way of negotiation,

whatever fragments of my territory we can save from the

avidity of my enemies"

In other words, Frederick was resolved to seek a soldier's

death on the first opportunity. Amazingly, one step

from his last gasp, Frederick received the gift of a

lifetime.

|

|

Without warning, the Russia Tsarina died.

The sudden death of Empress Elizabeth of Russia in January

1762, led to the succession of Peter III to the Russian

throne.

|

The new tsar was a great admirer of Frederick and decidedly

"pro-Prussian". On his orders, Russia's attack on

Prussia evaporated. Now that Russia was gone, this

event led to the collapse of the anti-Prussian

coalition.

As an interesting footnote, Peter III was Tsar

for all of six months. Peter III was, shall we say,

basically unfit for rule. Indeed, his move to call off

the war was extremely unpopular back in Russia. The

ruling class was fully aware that dangerous Prussia had been

on the ropes. They were horrified to see Russia let

Prussia survive once it was cornered. Put the stake

through the vampire while you can.

Nope, too late. Prussia was safe thanks to this stroke of

fortune known as the "Miracle of the House of

Brandenburg". Frederick was free to rise again.

This unconscionable mistake led to widespread resentment towards Peter back in

Russia.

Noting just how unpopular the public sentiment

was towards her husband, Peter's wife

Catherine the Great persuaded her boyfriend at the

time to

eliminate the Tsar. Peter's murder cleared her way to

become the next Tsarina. Isn't history interesting??

As for Frederick, although he did not gain any territory in

the Seven Years War, he had survived to live another

day. Indeed, the performance of the Prussian military

against all odds, his ability to retain Silesia, and his

amazing series of cat-like escapes made Frederick

extremely popular throughout the countless German-speaking

territories.

Meanwhile Empress Maria Theresa looked on with astonishment.

Foiled again. Maria Theresa would spend the rest of

her life claiming Frederick was a wicked man with a bad

heart who robbed Austria of Silesia and the alliance against

him had been his own fault.

She was right of course. Frederick clearly had a

wicked streak. But damn he was good.

|

Tsar Peter

III |

The Polish

Partition

At the end of the

Seven Years War (1763) Prussia was still

scattered across Europe.

Frederick is best remembered as a brilliant military

strategist, but he was also a realistic statesman. He

believed creating alliances was necessary, as Prussia did

not have the seemingly limitless resources of places like

France or Austria.

Frederick understood that for Prussia to

survive, he had to make deals.

Increasingly, all the talk in Europe revolved around the

phrase "Balance of Power".

The idea was to distribute military defense pacts so that no one state

was strong enough to

dominate all others by itself.

If one state gained inordinate power,

the theory predicted that it would use its

strength to attack weaker neighbors.

Every nation understood that those who stood alone risked

being conquered, so they made mutual defense alliances

promising to come to each other's aid if attacked. This

practice is said to have triggered the start of World War I.

But that's another story.

|

The

gap separating Brandenburg from Prussia had been a source of

irritation to Prussian rulers dating all the back to 1525

when Brandenburg first acquired Prussia.

Frederick had written it was his life's dream

to obtain the land necessary to unite the separate

territories. Once the Seven Years War was over, he intended

to do something about it.

|

Two people who clearly did not like each other were

Frederick and Catherine the Great.

Frederick knew

Empress Catherine II of Russia was staunchly opposed to

Prussia. She still couldn't believe her idiot husband

had let Frederick off the hook.

For that matter, Frederick opposed Russia as well. He

remembered with chagrin how Russian troops had been allowed

to freely cross the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during

the Seven Years War to attack Prussian homeland. He

hated the Russians and was desperate to obtain control of

certain Polish lands that would guarantee greater national

security from Russian attack.

One thing that has always amazed people about European

politics is the ability of bitter enemies to occasionally

work together despite their hatred. For example,

France's entry into the First Silesian War against Austria

had effectively handed Silesia to Prussia. Maria Theresa hated

France to the bottom of her soul for their treachery.

And yet eight years later, guess who became allies?

You guessed it. France and Austria decided to unite and gang up on Prussia in the Seven Years War.

In a similar manner, despite their personal hostility, Frederick

and Catherine had signed a defensive alliance in 1764.

This pact guaranteed Prussian control of Silesia in return

for Prussian support for Russia against Austria or the

Ottoman Empire. Both countries were more worried about Austria

and Turkey than each other. Considering alliances like

these changed at the blink of an eye, no country felt safe.

The threat of a secret alliance like the Prussian-French

trick in the First Silesian War kept statesmen awake at

night with fear.

So maybe Russia and Prussia were allies at the moment, but

Frederick kept a close eye on Russia nonetheless. Russia had been

a backwards nation lagging far behind the rest of Europe for

centuries. Now, thanks to a series of smart moves,

under Catherine, Russia was just now beginning to flex its

giant muscles.

As a side note, Catherine the Great and Frederick the Great

both clearly deserved the title of "Greatness". What

they did for their respective nations was incredible.

One can only wonder what these two gifted leaders living

side by side could have accomplished if they had trusted

each other enough to team up. If so, a Texas boy like

myself just might be speaking Russian now... or maybe

German.

But let's get back to our story. Now that his Kingdom was safe

following the Seven Years War, Frederick pondered his next

move. Frederick couldn't take his eyes off Poland.

The territory was a sitting duck and Frederick had a good

aim.

Frederick wanted to find a way to annex

the Polish territory that separated the two areas both to

unite his divided kingdom and to provide more national

security against any future Russian invasion.

Only one problem... what would Russia and Austria do if

Prussia moved on Poland?

Prussia, Russia, and Austria all coveted the Polish lands

that were there for there for the taking. But before

making a move, each country worried what the other two would

do. They stared at each other with fear and suspicion.

Each country knew that any Polish land grab would be opposed

by the other two powers. No one wanted to risk

provoking a two against one showdown.

|

So Frederick had a clever idea. Why not simply divide

Poland into three slices and each power take a slice?

That way they wouldn't have to go to war. So, under

pressure from Prussia, the three powers agreed on

the First Partition of Poland (1772).

Doesn't it seem strange that Poland was so cooperative while

being carved into three little pieces? As it turns out,

Poland had pretty much become a Russian protectorate over

the past century. Russia didn't "own" Poland, but it called all the shots.

Indeed, the current King... as well as the "Last King"...

was Stanislaw Poniatowski. Stan had been elected to

the position by the Polish nobles in 1764 thanks to the

support of Catherine the Great who "recommended him highly".

As it turns out, Catherine had a very high opinion of Stan

for a special reason. About 20 years earlier they had been

lovers. Catherine had gotten Stan this job as a

convenient way to end the affair. So when the issue of

the Polish Partition came up, all Catherine had to do was

smile and Stan went right along with the deal. Poof!

Polish independence went down the drain... which explains

why Stan was the last king Poland ever had.

In case you might be curious, Poland would not regain its

independence until the end of World War I. This took

place when the allies

ripped Poland away from Germany as one of many punishments

for starting the war.

|

The

annexation of

Royal

Prussia,

aka West Prussia, in 1772 accomplished Frederick's long-held

desire to link Brandenburg to Prussia.

|

The annexation of Royal Prussia in 1772 would mark Frederick's

final land acquisition.

Frederick had every reason to smile. He had finally

accomplished his lifelong dream and had even managed to do it

without bloodshed. Even better, as one can see from

the map, Royal Prussia was a giant piece of property

obtained basically "for free".

This brilliant move was yet another reason why Frederick was

widely admired... or greatly feared... throughout Europe.

Frederick had not only put Prussia on the map for good, the

country was now united and perfectly positioned to expand in

any direction it wanted to go.

Frederick's military victories and land acquisitions were

not his only triumphs. Once the Seven Years War

ended, Frederick was free to attend to matters of state.

He helped transform Prussia from a European backwater to an

economically strong and politically reformed state. His

conquest of Silesia gave Prussia's fledgling industries

access to raw materials. He protected industries with high

tariffs and minimal restrictions on domestic trade. He

promoted an advanced secondary education, the forerunner of

today's German grammar school system, which prepares the

brightest pupils for university studies. He made it possible

for men not of noble stock to use education to become judges

and senior bureaucrats. He

modernized the Prussian bureaucracy and civil service and

promoted religious tolerance throughout his realm. He

reformed the judicial system and abolished most uses of

judicial torture. It is said

that Prussian justice became the most prompt and efficient

in Europe.

In other words, Frederick's 46 year career as King of Prussia

was a remarkable one by practically any measure.

But he left a strange legacy behind. Frederick had an

intense dislike of the Polish people and the Jews. Nor

did he keep his opinions to himself. Frederick had

despised Polish people since his youth. Numerous

statements are recorded in which he expressed his anti-Polish

prejudice, calling Polish society "stupid" and stating that

"all these people with surnames ending with "-ski" deserve

only contempt".

He described Poles as "slovenly Polish trash". Once Prussia

acquired its Royal Prussia territory from Poland,

Frederick made life miserable for Poles living in that area. Frederick

invited thousands of German immigrants to the province,

openly expressing the hope they would displace the Poles

permanently. One can only wonder if Frederick ever

pondered more serious measures. Hmm. Doesn't

that remind us of someone?

Yes, it does.

It doesn't take much of an imagination to see why Frederick

was Adolph Hitler's personal hero.

Adolph Hitler obviously studied Frederick the Great's career

very carefully. Indeed, Hitler was

quoted as saying, "Despite all Napoleon's genius, Frederick

the Great was the most outstanding man of the eighteenth

century."

Hitler would spend his entire life hoping to be "the next

Frederick".

•

Hitler's desire to create the Master

Race parallels Frederick's disdain for the

impurities caused by the Poles and Jews in a highly

disturbing way.

•

Hitler's desire to unite all the

Germanic people by whatever means necessary seems identical to

Frederick's similar goals.

•

In fact, some historians have pointed out that Hitler's

refusal to surrender when all hope was gone may have been

rooted in his belief that some miracle rescue would come

along in the same manner as Frederick's "Brandenburg

Miracle".

|

Today Frederick is

regarded as one of the great geniuses of military history.

He and Napoleon are

clearly the most admired military leaders studied in the

well-regarded military treatise On War written by

Clausewitz.

Clausewitz praised Frederick's use of the

oblique order to attack numerically superior forces plus

Frederick's quick and skillful movement of the Prussian

troops.

Frederick had other strengths as well. He was brilliant at

preventing the unification of numerically superior opposing

armies. He had a keen ability to arrive at the right

place at the right time to keep enemy armies out of vital

Prussian territory at the last moment.

As the map indicates,

following Prussia's conquest of Silesia,

Brandenburg-Prussia territories were scattered

across Europe in seven different places.

A quick glance at the map reveals

Prussia had nowhere near the land resources of countries

like France, Russia, Spain and Austria.

Even with Silesia,

Prussia was small in comparison to the great powers of

Europe. This means Frederick's accomplishments were

even more impressive considering that Prussia had such a

size disadvantage.

|

Silesia was Frederick's greatest triumph, but he wanted

more. Note that the Prussian territory was divided into seven

different segments in 1748. Frederick wanted to unite all those

pieces, but he was determined to begin by uniting Prussia and

Brandenburg. That meant that sooner or later Poland was in trouble.

|

This fact alone makes

one realize Frederick was taking quite a chance taking on

much larger enemies such as Austria, Russia and Poland.

This guy was willing to roll the dice.

Frederick wasn't just a

smart man, he was also a brave man. He frequently led

his military forces personally. Over time, he had six horses

shot from under him during battle.

His courage, his

intelligence, and his statesmanship are testimony to his

greatness. To accomplish what he

did with so little explains why history has been kind to

Frederick.

Napoleon Bonaparte was

17 when Frederick died. Napoleon studied Frederick

closely and became a great admirer of Frederick.

Bonaparte viewed the Prussian king as the greatest tactical

genius of all time.

After Napoleon's

victory of the Fourth Coalition in 1807, he visited

Frederick's tomb in Potsdam he remarked to his officers,

"Gentlemen, if this man was still alive, I would not be

here".

A very fitting tribute

indeed.

|

|

|

|

|

Prussia

After Frederick

|

Following Frederick's death in 1786, Poland proved to be the

gift that kept on giving.

After the First Partitions took place in 1772, the Poles

living in the Russian sector were miserable.

Emboldened by the 1789 French Revolution, they attempted to

regroup and try to win back their freedom from Russia.

However, they knew Russia would likely intervene, so they

recruited their next door neighbor Prussia to be their ally.

The Polish-Prussian Pact of 1790 was signed, giving

hope that the Polish Commonwealth had found a powerful ally

that would shield it from Russia while the country

reorganized.

|

Empress Catherine was clearly angered at this bold move.

How dare Poland try to do anything without Russia's

permission!!

Arguing that this upstart Poland had fallen prey to the "dangerous ideas"

emanating from France, Catherine ordered Russian

forces to invade the Commonwealth in 1792.

And what about Poland's formidable ally? Well, mighty

Prussia took one look at the Russian forces moving in to

Poland and stepped back. Poland was on its own.

Poor Poland. They had chosen the wrong country to be

their ally.

Obviously Poland's rebellion folded like a wet rag.

But then Prussia did something interesting. Just as

the Russian forces were ready to withdraw, Prussia asked

Russia for more territory as "compensation" for not lifting

a finger in Poland's defense.

Catherine the Great was astonished at Prussia's nerve to

expect territory in return for doing nothing. But then

she shrugged. Why not? This was an excuse for

Russia to "legally" annex more Polish territory, so she

threw Prussia a bone to shut them up.

And what a bone it was. In 1793 Prussia received Posen,

a gigantic slice of territory given in return for doing

absolutely nothing other than betray its ally and stick out

its hand.

|

The

annexation of

Posen in 1793

linked

Royal

Prussia

in the north to

Silesia

in the south.

|

This would be the only clever move ever made by Frederick

William II, Frederick's successor.

A

likely homosexual, Frederick the Great had left no heirs.

What a shame, because his nephew Frederick William II

definitely took his eye off the ball. Pleasure-loving

and indolent, he is seen as the complete antithesis to his

illustrious predecessor.

Fred was a lover, not a fighter. Fred hated all things

military and turned all war details over to the officers the

moment he was crowned in 1786. At this point, the once

vaunted Prussian army began to slack off. Not one

notable victory took place during Fred's reign of

womanizing.

Yes, Frederick William II had a definite weakness for women.

In addition to fathering seven children by his second wife

Frederica, he spend considerable time with his lovely

mistress Wilhelmine, by whom he fathered five more

children. In addition, he fathered yet seven more

children with two other mistresses. That makes 19

children if anyone is counting. One has to wonder if Fred

knew all their names.

When Fred wasn't in the arms of his wife or his endless

string of mistresses, he could be found practicing the cello

and playing Mozart tunes with his beloved private orchestra.

How this man found time to attend to the affairs of state is

a good question. The answer is a simple one. Fred

didn't pay much attention to anything other than women and

song.

In the end, other than his potent sperm, it could be said Fred had only one

real talent - he was a master at being unfaithful.

Ironically, this proved to be his secret weapon in politics

as well. Fred's only positive accomplishment -

acquiring Posen - came to Prussia through betrayal.

Let's hear it for the cheater!

Frederick

William III

After Fred the Dread, the next batter up was Frederick

William III (1770 - 1840). He was king of Prussia

from 1797 to 1840. Unlike his father, Frederick

William III was a good man.

He was a melancholy boy, and with good reason. He was

completely ignored by his parents. His father was far

too busy chasing mistresses up and down the halls of the

palace to pay attention to his son, so Frederick was raised

by tutors. Disgusted by what he saw, young Frederick

grew up pious and honest.

Frederick William III received the usual extensive

military training expected of a Prussian prince. In

1793, Frederick William married Luise of Mecklenburg-Strelitz,

who bore him ten children. From his palace in Berlin,

Frederick William lived a civil life with a problem-free

marriage. His wife Luise was particularly loved by the

Prussian people, which boosted the popularity of the whole

House of Hohenzollern, including the King himself.

Frederick William succeeded to the throne in 1797.

Disgusted with the moral debauchery of his father's court

(in both political intrigues and sexual affairs), Frederick

William's first endeavor was to restore morality and dignity

to his dynasty.

The new King showed that he was earnest about his good

intentions. He reduced the expenses of the royal

establishment, dismissed his father's ministers, and

reformed the most oppressive abuses of the late regime.

Although Frederick William tried very hard to be a good

king, he was unlucky in three ways.

First, his father's deadbeat reign had seen the vaunted

Prussian military lose its pride.

Second, he lacked genuine talent. He had the

Hohenzollern determination to retain personal power but not

the Hohenzollern genius for using it. Too distrustful to

delegate responsibility to his ministers, he lacked the will

to strike out and follow a consistent course for himself.

Instead of acting, he reacted. Unfortunately this made

him a step too slow to succeed.

His final stroke of bad luck was being the guy in charge

when Napoleon came knocking.

|

Wilhelmine was described as smart, ambitious, and

voluptuous. Too bad she wasn't running Prussia.

Frederick William III

|

|

Napoleon

|

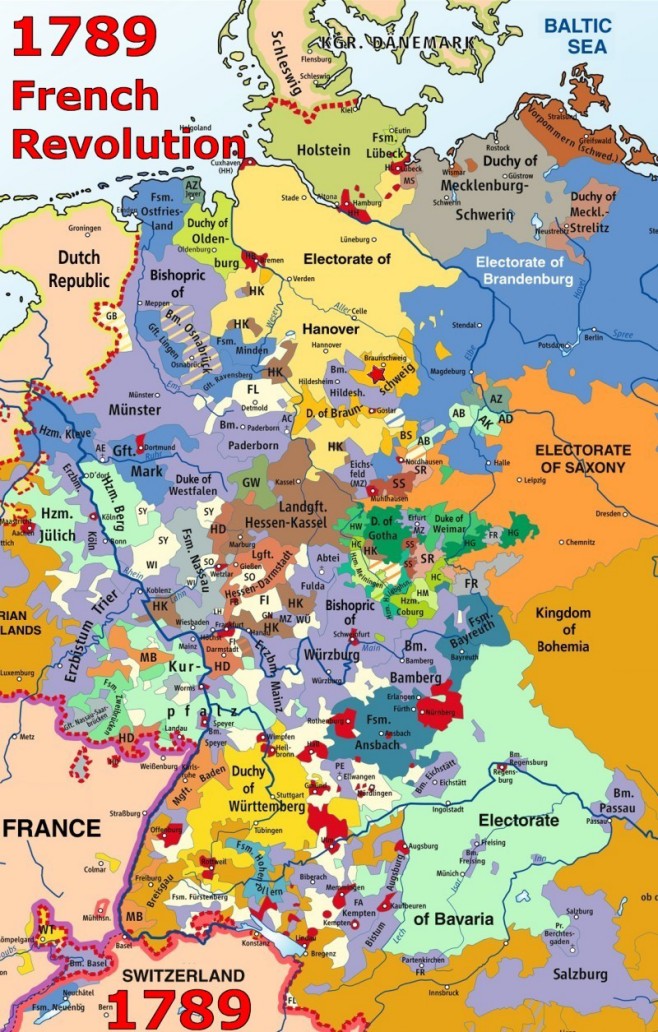

As

1800 loomed, Germany was now the great prize. It was a

vast, rich territory that was so horribly divided that it

was practically begging to be invaded by someone.

Considering there was no central leadership to coordinate any

effective resistance, Germany was ripe for the picking. Napoleon walked

through Germany like it wasn't even there.

With

Napoleon sweeping through defenseless, divided Germany, he

knocked off one small territory after another like bowling

pins. Now Prussia decided to take a turn at trying to stop

the Sicilian menace.

So who would you rather have leading your army against

Napoleon, one of the greatest warriors of history?

Would you rather have an evil genius like Frederick the

Great or a pious, decent church man like Frederick William

III?

Docile and slow to recognize the growing French threat,

Frederick's decision to go to war ended in national

humiliation. On 14 October 1806, at the Battle of Jena-Auerstädt,

Napoleon rolled through Frederick's Prussian army like it

wasn't even there.

Thanks to the total collapse of the once-proud Prussian

army, the royal family fled to Memel, East Prussia, where

they fell on the mercy of Emperor Alexander I of

Russia to protect them.

Alexander, too, would soon suffer defeat at the hands of the French.

In 1807 at Tilsit, Poland, on the Niemen, France made peace

with Russia and Prussia.

Napoleon dealt with Prussia very harshly, despite the

pregnant Queen's personal interview with the French emperor.

Prussia lost many of its Polish territories, as well as all

territory west of the Elbe. Plus it had to finance a large

indemnity and pay for French troops to occupy key strong

points within the Kingdom.

Furthermore, Prussian troops were forced to fight for

Napoleon in his next campaign against Russia. Each

time he defeated a country, Napoleon ordered the country to

contribute men to his army. Then Napoleon would go against

the next country twice as strong.

By the time Napoleon reached Russia, he had completely

shattered the European balance of power that had kept the

various countries in check for centuries. His Grande Armée had grown to preposterous dimensions;

his force of

600,000 men consisted of troops not just from France, but

troops from Prussia, Italy, Germany, and Austria as well.

Russia's army was terribly outnumbered. It

was one single country - Russia - against men from five

countries with Napoleon leading them.

What betting man would have given Russia any chance at all?

Amazingly enough,

Napoleon had made the worst mistake of his life trying to

attack Russia.

Russian forces almost never engaged Napoleon in direct

battle. Instead, their armies retreated and retreated,

burning all food supplies in the process.

Countless Russian peasants died of starvation, but

Napoleon's men were now running low on supplies.

Napoleon understood the danger he was in, but he believed he

would find food in Moscow. So he kept on going deeper

into Russia. Finally he reached Moscow. That's

when the Russians decided to burn Moscow to the ground. Who

burns their own capital? Napoleon never saw that one coming. Checkmate.

Napoleon was forced to retreat in dead of the Russian

winter. Starvation and bitter cold killed countless

men. Cossacks raiding his flanks at every turn did the

rest. By the time Napoleon finally reached safety in Poland,

his numbers had dwindled to 100,000.

The events of Napoleon's 1812 march on Moscow is one of the

most fascinating stories in all military history. If you are

curious,

Road to Moscow.

|

Napoleon at Jena-Austerlitz, 1806

The

long road home to France after the Russians burned Moscow.

|

| |

|

1801

Treaty of Lunéville

|

Ironically, Napoleon, Prussia's greatest enemy,

inadvertently did more to advance German Unification than

any other person since Charlemagne.

During the French Revolution, a process had begun whereby

the hated nobility was attacked in every way possible.

Some lost their heads, some lost their lands, many lost

both. Almost all the lands owned by the French nobles were

confiscated and given to the State of France. In addition,

many of the lands owned by the Catholic Church were taken as

well.

However, not all the stolen property belonged to the French

nobles. As it turned out, many of the confiscated

lands belonged to German princes living east of the Rhine.

They demanded to be compensated. After all, they owned

the hereditary title to the land.

There was no way France or Napoleon was going to give these

properties back. Once Napoleon came to power, he

wanted it understood that these territories PERMANENTLY

belonged to France. But he acknowledged the German

princes had a rightful claim that might come back to haunt

France down the road.

After consolidating his own position in France, Napoleon

chose to expand France's domain. Shortly before 1800,

he began to attack the Habsburg Empire... or Austria... or

the Holy Roman Empire... whatever you want to call it.

Napoleon won battle after after battle. After

particularly stinging defeats in Italy (Marengo 1800)

and Bavaria (Hohenlinden 1800), Austria/HRE/Habsburg

was down on its knees and begging for peace.

With the Treaty of Lunéville in 1801, French Napoleon

made out like a bandit. He had the Holy Roman Empire sign

over all German territories left of the Rhine River.

Another clause in the Treaty of Lunéville

acknowledged these territories had once belonged to various

German princes, who now deserved to be compensated.

Holy Roman Emperor Francis II was obliged to say he agreed

France now owned all those lands west of the Rhine and that

the compensation process was legal.

So what did all this mean??

It meant that France agreed these men were owed

compensation, but the Holy Roman Empire was put in charge of

paying the debt. In other words, the Holy Roman Empire

was being forced to reward the German princes not France!

So where was this "compensation" land supposed to come from?

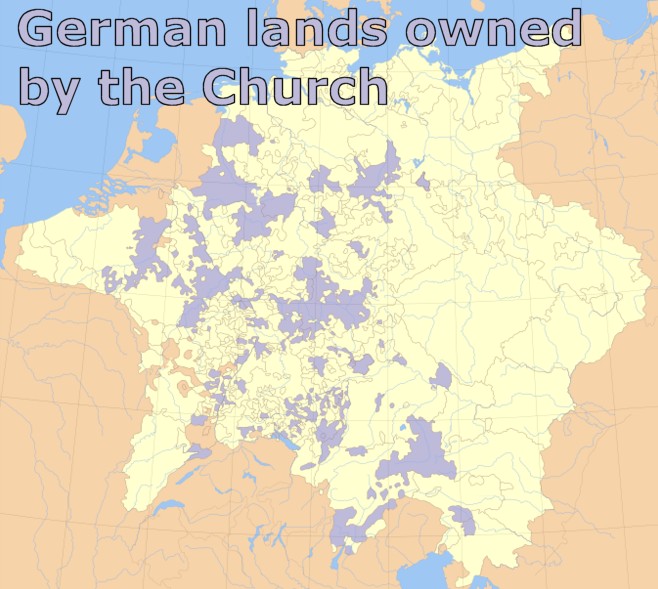

The

Catholic Church was about to be stripped bare through a

process known as Secularization whereby the secular

lands held by an ecclesiastical ruler such as a bishop or an

abbot to a secular ruler were redistributed.

To satisfy the terms of the Treaty of Lunéville, The Holy Roman

Emperor had little choice but to take possessions owned by the Church and

give them to the German princes instead.

Mediatization was another means of compensation. Here

the Emperor allowed many smaller German states to be annexed

by larger German states.

What utter chaos. Overnight an incredible amount of money,

stuff, citizens, and territory (most of which had belonged

to the church) began to change hands.

The outcome was the most extensive redistribution of

property in German history before 1945. The rationale had

been to compensate those rulers who had lost territory to

France, but through quirks in the system, considerably more

territory was gained through massive secularization.

For example, Baden received over 7 times as much

territory as it had lost, Prussia nearly 5 times.

Hanover gained the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück, even

though it had lost nothing. In other words, in trying

to keep favor with the German princes, his power base, the