|

Tsar Alexander

IAt

the time of

Paul's assassination, his son was actually in the palace. Surely

Alexander, 23, heard the piteous screams

of his father being stabbed to death.

As Nicholas Zubov, one

of the assassins, made his way out of the castle, he saw Alexander

standing there pale as a ghost. Alexander knew just what had just happened.

The general said, "Okay,

boy, you're the Tsar now. Time to grow up! Go and rule!"

Was Alexander

involved in his father's death? Probably, but not in the

murder. Few facts exist. Count Pahlen,

one of the conspirators, used his position to destroy many documents that could

have shed more light on the details.

The best guess of the historians is that

Alexander gave his consent to the coup, but stipulated it could take

place only on the strict condition that his father's life be spared. Obviously

he trusted the wrong people to do his dirty work.

...Oops!

Hey, sorry, kid, but we got drunk and accidentally killed your dad.

Too bad, but it was his own fault for not doing what we told him

to do...

Unlike his predecessors, Peter the Great

and Catherine the Great, Alexander had a weakness known as a

conscience. He had just been a party to his father's own

murder.

Why Alexander agreed to

allow it to happen is the million dollar mystery. By all

accounts, Alexander was one of the most principled and spiritual men

to ever ascend to the Russian throne. Furthermore, his father had not

been mean or evil to Alexander. Nor did Alexander seem

power-hungry. Without a clear motive, this situation remains a riddle.

|

Gaining Tsardom through this hideous crime

surely created some nightmares. Knowing he had a hand in his

father's death instilled a remorse in Alexander that would linger for

the rest of his life.

Apparently nobody bothered

to tell Paul's wife Maria Feodorovna what

was going on. Shortly after her husband's

assassination, Maria Feodorovna remembered how

Catherine the Great had succeeded her own

murdered husband Peter III. The next morning Madame Feodorvna tried to

proclaim herself Empress. The conspirators

told Alexander to set her straight.

It took Maria's son, Alexander I, several

days to persuade her to relinquish her reckless claim.

"Gee,

Mom, they killed Dad so that I could be the

ruler, not you."

That's when Maria

Feodorovna figured it out. For some time afterward, whenever her son

Alexander came to visit, the Dowager

Empress would place a casket between them containing the

bloodstained nightshirt that Paul was wearing on the

night of the

murder.

Eventually the

strained relationship between mother and son improved.

Since his mother Maria Feodorovna

was only forty-two years old when she became a widow,

Alexander made sure his mother kept the

highest female position at court. From this point

on, his wife Louise was forced to appear after her mother-in-law at

all public events. Of course Louise didn't care for this

arrangement, but she accepted it.

The Early

Years

Considered by many to be

a sensitive soul, Alexander began his rule in 1801 with many lofty principles

and ideals. Growing up at the feet of his illustrious

grandmother, Alexander was Catherine the Great's hand-picked

successor. The Golden Prince had received more training in advance

of his role than any previous Tsar other than Peter the Great.

It had been 5 years since Catherine died and now he was ready.

The country was very excited at the prospects of

Alexander's reign; there were great hopes for the future of Russia

and the anticipation of a more liberal form of government and

increased freedom for serfs.

At first the Tsar did

little to discourage these aspirations. Alexander did everything he

could to act on his noble ideas. However, he soon discovered the hard way

that the nobility of Russia refused to cooperate unless they had no

choice. The Russian system allowed wealthy people to get much

wealthier while the majority of the population lived lives of

poverty and desperation. There was practically no such thing

as upward mobility. The nobles liked this system just fine.

To ask them to sacrifice for the good of the people was a concept

they could not even begin to conceive.

Catherine the Great had come up

against the same entrenched attitudes and hadn't gotten very far

either.

Paul had lost his life trying to change things. Peter the

Great was the only one to make any progress. If someone didn't

follow his orders, he just cut their head off.

Alexander was a little

too gentle to start lopping off heads. So he didn't see much

progress with his social reforms.

Frustrated and

demoralized, Alexander turned away from his childhood dreams and

principals. Increasingly he found it easier to get results by using

the power of autocracy. Once he began using autocratic power,

administered through men who served at his will, it corrupted him.

The longer he used this method of ruling Russia, the more difficult

it made it to return to the principals of good government he had

learned in his youth. Alexander turned cold and cynical.

However, very few people

remember much about Alexander's role in running the government.

Alexander is famous as the first man to ever stop Napoleon in his

tracks. The two men would go down in history as closely linked

adversaries.

|

|

Napoleon and

Alexander

The underlying story of Alexander in regards

to the intimidating French dictator is how Alexander started out as a

weakling and grew to be a man... just as Zubov, the man who killed

his father... ordered him to. The highlight of Alexander's monarchy came

when he refused to knuckle under to the bullying tactics of Napoleon Bonaparte.

Alexander started out as

a friend of France. His French tutor La Harpe had instilled in

him a love for the principles of the French philosophers. In

addition, the language and the customs of the French played a

significant role in St. Petersburg society.

However, when Napoleon

began his conquests, Alexander became skeptical of Napoleon's

motives. In October 1801 Alexander dispatched La Harpe to

France to discuss common ground between the nations. For a

while it seemed as though France and Russia might come to an

understanding.

Carried away by the

enthusiasm of La Harpe, who had returned to Russia from Paris,

Alexander began to openly proclaim his admiration for French

institutions and for the genius of Napoleon Bonaparte, the man who

was turning France into a superpower.

However, after his next

visit to France, La Harpe warned Alexander that his opinion of

Napoleon had changed dramatically. He believed Napoleon was

quite likely a tyrant.

When Alexander learned of

Bonaparte's cold-blooded execution of the Duke of Enghien

on trumped up charges (1804), it became obvious to him that La Harpe was

correct. The Duke was an innocent man. Napoleon

simply wanted to get rid of the man. Bonaparte talked a good game,

but was a gangster at his core.

Alexander broke off relations with France and

entered into a coalition aligned against Bonaparte. Meanwhile

Napoleon was surprised. Russia could be very useful to him as

an ally. Napoleon never gave up hope of detaching Alexander from the

coalition.

|

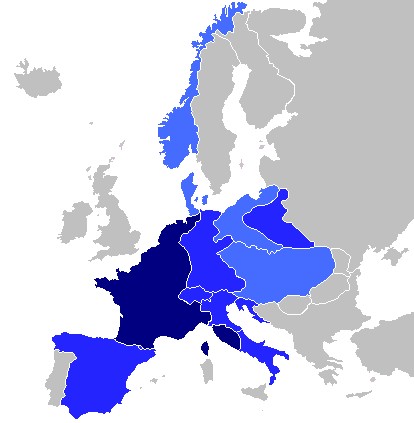

Austerlitz 1807

In 1807 Napoleon took his

army to Austria. At the Battle of Austerlitz, the French badly

whipped the alliance of Prussian, Austrian and Russian forces.

Napoleon had no sooner

entered Vienna in triumph than he opened negotiations with

Alexander.

Russia and France,

Napoleon urged, were geographical allies. There was no true

conflict of interests. Russia could operate at one of end of

Europe, France could operate at the other end of Europe.

Their sphere of

operations could stay exclusive. Working together the two

countries might rule the world.

But Alexander was not

persuaded by Napoleon's offer to cut the world in half. Alexander preferred to

stick with his allies.

|

|

|

Friedland

1807

Once again Alexander

allied himself with the Kingdom of Prussia to take on the French war

machine.

Once again Alexander had

defeat rammed down his throat. He was learning the hard way

about France's military superiority.

The Battle of

Friedland (June 14, 1807) saw Napoleon I's French army decisively

defeat Count von Bennigsen's Russian army in

Friedland on the Polish-Russian border.

After the battle,

Napoleon saw another opportunity to turn the Russian Emperor.

Instead of demanding

punitive terms, he

invited Alexander to a private meeting.

|

Tilsit 1807

The two Emperors met at Tilsit

in June 1807. Napoleon

was only 8 years older.

Napoleon turned on the "big brother" charm. What kept these two

men from being personal friends? What stopped these two countries

from enjoying a partnership of glory? He offered

his alliance to the chastened autocrat for

the second time.

Napoleon knew just

how to appeal to the exuberant imagination of his new-found friend.

He would divide the world with Alexander.

Russia could have the Danube, Finland, and all of Turkey, India, and

any other Asian country he wanted.

Alexander, dazzled by Napoleon's genius and

overwhelmed by his apparent generosity, was completely won over.

His

anti-French feelings were changed at the personal meeting with

Bonaparte. Alexander agreed to partner with

France.

The agreement paid

immediate dividends for France. The

Continental System was a

large-scale embargo against British trade which began

in November 1806.

|

|

England was France's

greatest enemy.

Protected by the North

Sea, the greatest moat in history, invasion of the island of Great

Britain was out of the question. The only way France could

attack England was by breaking it economically.

|

So the France had a rule

- trade with England was forbidden.

Any country that

broke the rule could expect to be attacked. Since France occupied

almost all of Europe, few countries had the guts to oppose France.

Napoleon wasn't kidding. When Portugal resisted, Napoleon

immediately invaded the country. Napoleon understood that the

blockade of England was useless without total compliance.

This alliance with

Russia was important to France. All that remained to complete his

"Continental System"–a unilateral European blockade designed to

economically isolate Britain and force its subjugation–was the

cooperation of Russia.

After the Tilsit

agreement, Russia acted as France's ally against England. When Sweden,

Britain's ally, refused to comply with French demands, it was

invaded by Russia in February 1808 in accordance with the Tilsit

agreements. Napoleon was pleased. His recruitment of

Russia was paying immediate dividends.

Napoleon was right.

If Alexander had accepted his role as junior partner and cooperated

closely with Napoleon's ambitions, the world today might be divided into

French West and Russia East.

However, there were two

things that kept it from working. Alexander did not share

Napoleon's ease at sending people to their death and Napoleon

didn't play well with others. If Napoleon had looked inside a little

deeper, he would have admitted he would never share the glory.

There was only room on this continent for one Emperor.

|

|

|

As the years

went by, Alexander grew increasingly suspicious of

Napoleon's motives. Napoleon had promised to let

Russia deal with the countries of the Danube such as Austria

and Prussia. However, rather than allow Russia to deal with

the countries of the Danube, French forces stayed in the

area. Russia maintained its alliance with France, but

Alexander grew ever more suspicious.

Franco-Russian relations became

progressively worse after 1810. Napoleon

was angry with Russia because he suspected that

Russia and

England had been trading secretly for some time. And

he was right. Before the war, England had been

Russia's main trading partner. Russia chafed under the

embargo and decided to begin trading again on the sly.

Meanwhile,

Napoleon continued to annex parts of Austria and Prussia.

Alexander began to entertain the idea that Napoleon was

playing him for a sucker. Contrary to the Napoleon's

promise of dividing the world into two spheres, Napoleon's

armies remained uncomfortably close to Russian borders.

By 1811, it became clear

that Napoleon was not keeping to his side of the terms of

the Treaty of Tilsit.

Meanwhile, this

Continental System was ruinous to the Russian economy. So,

in 1812, Russia broke the agreement of Tilsit and began to

trade openly with England. Napoleon was furious.

He moved his

army closer and closer to Russian borders.

When

Napoleon annexed a slice of Poland that Alexander had warned

him to leave alone, Alexander issued a blunt warning - back

off from Poland or expect retaliation.

No one talked to

Napoleon like that, especially a pipsqueak Tsar with a

third-rate army. Napoleon had increasingly come to view

Europe as his own domain. Napoleon didn't particularly

desire war with Russia, but his habit of subjecting every

country to his will was clearly leading to a conflict of the

Titans. France already had all the territory it needed

for its glory, but the Tsar's defiance intrigued him.

Someone needed to teach Alexander a lesson.

|

|

War With Russia

In 1812, French Emperor

Napoleon I was at the height of his fortunes. The Peninsular

War against Spain and Britain was a thorn in the side of his great European

empire, but he was confident that his generals would soon triumph in

Spain. Now Russia had just sided with England, his greatest

foe. Napoleon needed the continued cooperation of Russia to

economically isolate Britain and force its subjugation.

To intimidate Alexander

back into compliance, Napoleon massed his forces in Poland in the

spring of 1812 along the Russian border. Still the Tsar resisted.

In Dresden, Napoleon

invited his staff to discuss invading Russia. There was an

unusual amount of disagreement. There was only one man in the

room who thought it was a good idea.

Napoleon stood up and

asked for quiet. He began a speech about certain victory.

“Russia is a

semi-Asiatic nation which cannot field an army as large as your

own, and has no literature or music to speak of.

It is a barbarian

nation, and barbarians are superstitious and have simple ideas.

A single blow delivered at the heart of the Russian Empire, at

Moscow the Great, Moscow the Holy, will, in a single instant,

put this whole blind apathetic mass into despair.

Alexander will come back to me, just as he did at Friedland.”

Seeing that Napoleon had

his mind made up, there was no further dissent.

|

Napoleon's invasion of

Russia commenced on 24 June 1812 with the crossing of the Nieman

River which acted as the border between Russia and Poland. Napoleon had sent a final offer of

peace to Saint Petersburg shortly before commencing operations.

He never received a reply, so he gave the order to proceed into

Russian Poland.

This began one of the

most extraordinarily military campaigns in history. It certainly is

one of the most heavily analyzed. One reason for the intense

study is all the unanswered questions.

Napoleon never wrote

any memoirs commenting on his inner thoughts, so diplomats and war

strategists alike have tried to read his mind ever since.

|

Napoleon was still

waging war with Spain. Did he really want to take on two

fights at once?

Napoleon was taking a

huge risk invading this vast foreign country so far from home.

Defending the supply lines would be tricky. Furthermore, no matter how weak the military, it is never easy fighting desperate

people defending their home soil and families. Finally, the attack seemed

to have so little practical value. Yet Napoleon never

hesitated. Most historians have concluded

Napoleon's attack on Russia was more ego-driven. Napoleon

couldn't stand the thought that the Tsar was defying him.

Another conclusion is

that Napoleon based his decision on several factors that didn't pan

out. One, he assumed his army could live off the land just as

it had in every other country it had attacked. Two, he took

Alexander to be a coward. He expected Alexander would see his

armies being destroyed and panic. Alexander could never

stomach all the

destruction Napoleon's army was so famously capable of.

Napoleon fully expected Alexander to crumble at the first major

military loss and come rushing to the bargaining table.

Misjudging the Tsar was

Napoleon's biggest mistake. Alexander wasn't always a

practical man. There was a side to him that said this coming

battle was a struggle for the soul of mankind, good versus evil.

At some level, Alexander believed it was his sacred duty to God to

stop Napoleon no matter what the cost...

Refusing to be cowed by the appearance of

the French army on his borders in 1812,

Alexander showed remarkable strength of character.

Alexander famously spoke,

"If the

Emperor Napoleon is determined on war and if fortune does not

smile on our just cause, he will be forced to go to the end of

the world to find peace."

|

The

Secrets of Napoleon's Success

Napoleon had an

almost total disregard for the military power of Russia.

With a force

estimated at half a

million men, the Grande Armée

marched confidently through

Western Russia. "Within a month we

shall be in Moscow," announced

Napoleon

cheerfully. "Within six weeks, the Russians will sue for

peace."

Napoleon

initially met little resistance. The French won

a series of

early engagements

and moved quickly into the enemy's

territory. Napoleon wanted to be in Moscow in one month.

He might get there sooner at this rate. Some of his

generals had completely disagreed with his decision to enter

Russia, but Napoleon wasn't worried. For many years

now he had beaten far more formidable armies than the

disorganized Russians. Napoleon had won these battles

through superior military strategy.

|

It

had all started

with a brilliant new

philosophy -

speed and

maneuverability.

Napoleon got his

start by asking this question - how could he command

such a large group of people but still retain the

flexibility that he had with his smaller artillery units?

He took

the controversial approach of radically decentralizing his

command. He broke the army up into smaller divisions of men

commanded by field marshals. These marshals had nearly

complete autonomy as long as they followed the strategic

objectives outlined by Napoleon. The

marshals had permission to react to problems instantly.

Napoleon also introduced

a technical innovation into his

army

- the backpack. All of his soldiers carried 60 pound

packs that provided them with enough food and water for a

week. They were taught to live off the land by hunting and

foraging. This freed the soldiers

from the slow supply caravans and allowed them to remain

independent for long periods of time.

With smaller forces that did not need to be connected to the

supply lines, Napoleon was able to invent a new kind of

fighting - maneuver warfare.

While most

European generals were trained to develop complicated battle

plans in advance, Napoleon believed this was a waste of time

because no one could possibly predict every action of the

enemy in advance.

There was too much uncertainty inherent in every battle

situation. Victory depended on the ability to react

quickly to changing situations. By trusting all

decisions to be made by the

commanders who had the best perspective on the

field, Napoleon

gained a huge advantage over his competitors.

Entering Russia,

Napoleon had never lost a major campaign.

|

|

Napoleon's Confidence

Now that he was

in Russia, Napoleon was

impressed with himself.

He had

undertaken the greatest attack of his career - a 600 mile

trip across hostile, barren territory to Moscow. It

had never been done before. The Mongol Horde had

skipped Moscow because it was too far out of their way.

"Moscow is an outpost on the very distant edge of

civilization," Napoleon chuckled, "that is, assuming Russia

could be called a civilization."

Napoleon was

fascinated by the story of Charles XII of Sweden who had

failed miserably one hundred years earlier in 1709 in his

attempt to take Moscow. At every opportunity, Napoleon

amused himself by reading about Charles XII's foolish

invasion of Russia in pursuit of Peter the Great.

Charles had ultimately been beaten by Peter the Great's scorched

earth strategy and guerilla warfare.

Napoleon paid

attention. He was

well aware that he too was facing supply issues. After

all, he himself had once said, ‘An army travels on its

stomach.’ By this, he meant that the problem of

keeping an army supplied is a prerequisite for the very

existence of the force. Napoleon had taken extra

precautions to make sure his supply lines were intact.

As Napoleon

memorized every minute detail - geography, topography,

history, population, weather - it never seemed to dawn on him that the

same fate that Charles had faced might await his army as

well.

Closer and

closer to Moscow they come...

|

| |

|

Scorched Earth Strategy

|

|

|

|

|

|

Barclay de

Tolly

The Russians were under

the command of Barclay de Tolly. Barclay was a

foreigner. He grew up speaking German in Livonia

(modern day Estonia).

Barclay had been a member of the Russian

Military since 1776 at the age of 15. Rising through the

ranks, he achieved great notoriety by taking Finland from Sweden in

1809 thanks to some brilliant maneuvers in a snowstorm. That

success earned him a promotion to Commander of the entire Russian

army.

Barclay had spent his

entire career studying Napoleon. Barclay had faced the military

genius in battle several times as commander of smaller units.

After the inevitable defeats, Barclay would try to figure out what

had gone wrong. As Barclay watched the European generals

lose one battle after another to this great disrupter, he looked for

weaknesses he could exploit.

As a member of the

Russian military, Barclay was quite familiar with the scorched earth

strategy Peter the Great had used to defeat Sweden's King Charles.

Could this work against Napoleon?

Barclay noted the

similarities of the two situations. Both Charles and Napoleon

had vastly superior armies. Both Charles and Napoleon were

very far from home.

Seeing the Russians

stood little chance of winning a head-to-head war, Barclay

proposed the now famous

Russian scorched earth strategy

against Napoleon. The Grande Armée

was so large it could practically form a ring around the Russian

army. Only a fool would engage such a vast force directly. Let the Russians constantly retreat.

By drawing the enemy deep into Russian

territory all the while burning crops to deprive them of

food and disrupting their supply lines, perhaps the Russians could starve the massive army to death.

The lead Russian command

consisted of Tsar Alexander, Prince Michael Barclay de Tolly, Prince

Pyotr Bagration and General Mikhail Kutuzov. These men talked

it over. They all shook their heads in consternation. No

one was quite sure Barclay's weird strategy would work. No one

liked it, that's for sure. It went against human nature which

of course is to resist force with force.

|

However, Barclay had

done his homework. He pointed out Napoleon's tendency to march

way ahead of the supply lines. He reminded them this strategy

had worked against Charles.

For good measure, he

reminded the men that

to engage the enemy directly would give the

French a

chance at a knock-out blow. It was

better to let them chase the Russian army across Russia and try to slowly

starve them to death.

Still the other generals

balked. Fortunately, Barclay had an ally. Karl Ludwig

von Phull was a German military strategist hired by Alexander

himself. Alexander had confidence in this man. When von

Phull wholeheartedly endorsed Barclay's plan, the die was cast.

Barclay got

permission to try his risky strategy.

Now as the giant French army

approached, Barclay played cat and mouse.

He would let the French get close, let the Cossacks conduct surprise

raids to slow down the approach, then retreat. Along the way

he would set his men to burn crops, burn homes, and always retreat

rather than to risk a major battle.

It wasn't easy. The Russian soldiers watched in horror as vast throngs of peasants

lost their homes and their food. Some peasants joined a huge migration to

the east; others chose to hide in the forests and let the French

pass by. Homeless, exposed to the cold and without food, the

death toll rose. The soldiers could barely stand the guilt as

their countrymen stared at them in hopeless confusion while they

destroyed crop after crop. These people were doomed.

This strategy revolted

the Russian generals as well. It might make sense on paper,

but it was painful to watch. This was Russian soil that this

foreigner Barclay was so blithely ceding to the French.

Furthermore, Napoleon's men weren't the only ones suffering.

Watching the Russian peasants starve to death right in front of

their eyes grated deeply on Russian sentiments.

Watching Napoleon move

deeper into Russian without opposition was equally terrifying.

What kind of defense was this? Why not stand up and fight like men?

|

|

Barclay was a very

unpopular commander.

No one trusted Barclay enough to agree this

was the right approach. His rival

officers spread

rumors that he was secretly an agent of Napoleon. The Russians

had been keenly opposed the appointment of

a foreigner as commander-in-chief in the first

place. The terrified populace condemned Barclay

as a coward. Now, behind his back, the

other Russian generals seemed to agree.

Barclay refused to be

bullied into fighting Napoleon. He knew full well that to

engage Napoleon in an open battle like the disaster at Austerlitz

was to play right into Napoleon's strong point. The quick

maneuvers of the French in the open field would surely doom the

untrained Russian army to a devastating defeat.

The

other generals weren't the only ones who were worried.

Tsar Alexander was panic stricken at the swift advance of the French.

|

|

Smolensk

Barclay's chief

critic was Pyotr Bagration, commander of a large Russian

unit. Bagration and Barclay bickered constantly over

this passive defense. Despite heated arguments,

Barclay refused to fight despite Bagration's urgings.

Finally

Bagration couldn't take it any more. Whether it was

conflicting orders or a breakdown in communication, no one

is certain, but Bagration basically disobeyed orders.

Anticipating a French movement, Bagration raced to defend

Smolensk to the south. When Alexander learned of this

decision, he took Bagration's side. After watching the

torture of the Russian retreat for two months, Alexander

couldn't take it any more. He ordered Barclay to go

and reinforce Bagration.

Given no choice,

Barclay

joined his rival to engage

Napoleon at Smolensk.

On August

16, French forces found the city heavily garrisoned by

Bagration's troops, further reinforced with the subsequent

arrival of Barclay and the main Russian army.

|

It took three days, but in the end

Napoleon won handily. He forced

Barclay to retreat when he threatened Barclay's only escape

route.

For some reason,

the ignominious defeat was pinned on the unpopular Barclay.

The scorched earth policy had created a deep well of

resentment. Now the loss of

the Holy City of Smolensk brought the

anger to a boil. The outcry of officers and civilians

against Barclay grew to a point

where the Tsar could no longer ignore it.

Noting that

Bagration hadn't helped matters with his disobedience,

Alexander had only one other choice - Kutuzov, the old man.

Alexander

appointed

Mikhail Kutuzov as the

over-all commander of the Russian Forces. Barclay remained

on staff as General of the 1st

Army of the West.

Inwardly,

Alexander shuddered. He personally disliked Kutuzov.

Alexander was not only

repulsed by Kutuzov’s grossly fat

physique, he still irrationally held

him responsible for the stinging

defeat at Austerlitz five years earlier

at the hands of Napoleon.

Alexander didn't

have much confidence in the man, but

Kutuzov was a

popular choice with the men on several accounts. They

liked that Kutuzov was Russian-born.

Kutuzov had been around forever. He went all back to

the glory days of Alexander Suvarov, the legendary commander

in the days of Catherine the Great who had never lost a

single battle.

Alexander

shrugged. Kutuzov was the veteran of many campaigns.

Most recently he had put a swift end to a Turkish struggle

that had seemingly gone on forever. Kutuzov was definitely

experienced. Maybe fat Kutuzov would surprise him.

|

|

|

Slow

Death

No one in Russia

would have ever guessed it at the time, but Napoleon's victory at Smolensk was

the beginning of the end.

To save the army, Barclay de Tolly

abandoned the city destroying all ammunition stores and

bridges. Leaving a small force

behind to

cover his retreat, Barclay ordered

the unthinkable - he gave orders to burn the city.

By

nightfall, most of the city was burning.

Napoleon was

aghast. The Assumption Cathedral in Smolensk

was home to

one of the most venerated icons of the Orthodox Church

- Our

Lady of Smolensk attributed to St Luke.

Napoleon assumed that the Russians would fight

outside the city to avoid its destruction.

Now this ancient holy place was in flames never to be seen

again.

Napoleon viewed

the burning city with growing concern. What kind of people

was he dealing with?

|

This was not a new

feeling. For some time now,

Napoleon had dealt with the

gnawing feeling

that these Russians were crazy. They would destroy

anything to keep his army from eating. They were

sacrificing their own people in the process, but that didn't

stop them. Napoleon shuddered. He understood the

civilized people of Europe, but these people still had a

touch of Oriental barbarism. They were a strange

people indeed.

Technically the battle of Smolensk

was a victory for Napoleon as he captured the city. However

his soldiers were already running short of food and its

destruction denied him access to food

within the city. It also deprived him of a useful supply base, adding to the

logistics problems caused by the Russian scorched earth

tactics. Seeing Smolensk burn to

the ground was a bad omen.

Everything Starts to Go Wrong

Many of the

Napoleon's

usual

methods of operation worked against him. It was only

August, but it was already starting to snow. The lack

of winter horse shoes made it impossible for the horses to

obtain traction on snow. With the horses hampered, the

forced marches often made troops do without supplies as the

supply wagons struggled to keep up.

The lack of food

and water in the thinly populated, agriculturally-ruined

regions now led to the first cases of death by starvation in

the French army. It wasn't the men who died, but

rather the horses. The

snows made food for the horses difficult to find. Both

men and their mounts were exposed to waterborne diseases

from drinking from mud puddles and eating rotten food and

forage.

The loss of the horses make it harder to keep the supply

wagons moving. People assume that Napoleon was

completely ignorant to the supply problem, but that was not

the case.

Napoleon had in fact made extensive preparations providing

for the provisioning of his army. Seventeen train

battalions, comprising 6000 vehicles, were to provide a

40-day supply for the Grande Armée and its operations.

A

large system of magazines was established in towns and

cities in Poland and East Prussia stretching to the border

of Russia.

What most people

don't realize is that Napoleon never expected to go all the

way to Moscow. Napoleon's plan was simply to enter Russia,

beat the pants off the Russian army in the first engagement,

and let Alexander come crying to his tent begging for peace

and forgiveness.

|

Therefore these

preparations would have sufficed. What Napoleon did

not anticipate was the refusal of the Russians to defend

their country. That surprised him... and angered him.

He fell for the bait. The retreat

of the Russian armies continued to lure the Grand Armée ever

deeper into Russia.

Now the French learned the hard way that

Russia had a poor infrastructure. Unlike the well-kept

roads of Europe, Russia's roads were pitiful dirt

paths.

The men,

wagons and horses were forced to travel narrow dirt roads

that would dissolve into deep mires with every rain.

The ruts in the mud caused untold problems, tripping already

exhausted horses and snapping wagon wheels.

|

The cold temperatures and lack of

available resources continued to take

their toll. Napoleon had

planned on scavenging for supplies to support his massive

army, but the Russians had destroyed all of their crops.

As a result, the army was heavily reliant on slow

supply trains from Europe that were unable to keep pace with

its quick advance. Common sense had

suggested taking this massive army into Russia worked to his

advantage, but now there were too many mouths to feed.

First it had been the horses, but now some of the men began

to die from

starvation and exposure.

Napoleon

grimly noted he had lost more men to hunger than battle. Nothing was

working as planned.

Then Napoleon got more bad news.

His attack on Saint Petersburg had just failed.

Russia was a

two-headed monster. It had a political capital in

Saint Petersburg and a cultural capital in Moscow.

From the start Napoleon wasn't sure which target made more

sense to attack. Moscow was his preference, but to

cover his bet he sent part of his army towards St.

Petersburg.

In a separate

battle on the same day as Smolensk,

the right wing of the Russian Army,

under the command of General Peter Wittgenstein, stopped

a wing of the French Army in the

Battle of Polotsk. This

prevented the French marching on the Russian capital at

Saint Petersburg. Napoleon frowned.

Had Saint Petersburg fallen, the war might have been over

right there.

|

Now the

fate of the war had to be decided on the Moscow front.

Napoleon had a tough decision to make. His troops were

hungry. That damn Barclay was making things miserable.

Barclay was leading the French on a wild goose chase through

barren land. Barclay was burning crops. Barclay

was burning bridges and forcing delays. Napoleon

cursed. It seemed like the army faced another

major river every other day. Each day lost building

pontoons meant another day of hunger.

But the worst

news of all was that the Russians were now raiding his

supply trains from the rear. His army was so far

extended into Russia that the Cossacks had found weak links

far

behind the main body of men.

The harassment of

the smaller forces left behind to defend his supply

lines meant further delays in getting new supplies.

Napoleon

cursed at the knowledge that those damn Cossacks were dining

well on his army's food supplies. Those Cossack raids were

making life miserable.

|

Should

Napoleon

retreat or move forward?

Napoleon took a

long breath. One part of him wanted to cut his losses

and head home. He had two objections. First, he

knew the lands behind him held no food. A retreat

meant a month of marching through land that could not feed

him. Second, this would be seen as a humiliating

defeat in eyes of Europe. Every country currently

cowering under the threat of French invasion would be

tempted to rise up against him if he turned back now.

Moscow was only

230 miles away. At the usual pace of his nimble army,

he could be there in two to four weeks. There in Moscow he would find the food and

shelter his army needed. Moscow was the most populated

and important city in Russia. There could be no doubt the

Tsar would beg him to spare Moscow and surrender

unconditionally. The conquest of Moscow would

guarantee that his reputation would stay intact.

Knowing

Napoleon, there could be no doubt which choice he would

take. Napoleon was a gambler at heart who liked to

bet on himself.

|

|

|

The Road to Moscow

|

It was now late

August, two months since Napoleon had entered Russia.

Napoleon had expected to take Russia in a month; he was

already a month behind schedule with no end in sight.

Napoleon

fumed. The roads were in such terrible shape

that progress was molasses. Plus it left his

men sitting ducks to raids.

Unable to move with

any speed, the Cossacks, gypsy warriors on fast horses,

continued their guerilla-style attacks on the French flanks

and rear.

Alexander was

rallying the people. Napoleon's invasion had accomplished a

miracle - for the first time in history, the Russian people

were united.

Cries of

"Victory or Death" resounded throughout the country.

From every corner of the vast nation, patriotic volunteers

trudged towards Moscow to swell the ranks of Kutuzov's ragtag

army.

Russia

was preparing to make it's defense of Moscow.

|

|

|

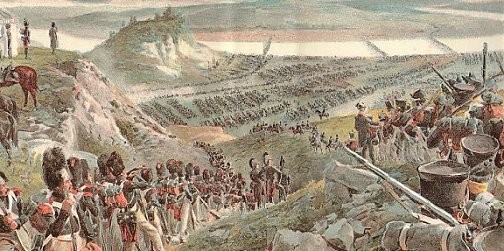

Bloody Borodino

Kutuzov had been quietly in

favor of Barclay's scorched earth tactics all along, but kept that

to himself. He knew better

than to incur the same wrath by letting it be known. He too

continued to retreat. However, as the French grew closer to Moscow, Alexander ordered Kutuzov to

take a stand. Scorched earth tactics and constant retreat be

damned. Alexander would not give up Moscow without a fight.

The fight took place

three weeks

after Smolensk. Kutuzov decided to

make his stand in a

series of rolling hills 70 miles west of Moscow.

|

The two giant

armies clashed at Borodino on 7

September 1812. The battle

involved a quarter of a million

soldiers. It was the greatest battle in human history

at

the time.

Napoleon was surprised

to meet a force almost as large as his own. The Russian spirit

had suddenly come to life! Countless Russians had come forward to

volunteer to fight. Many of them carried

little more than pitchforks, but they were ready to die if that's

what it took to defend Moscow.

And die they did. At the conclusion, the battlefield

was covered with the bodies of nearly 100,000 men.

Even the battle-hardened

Generals were shaken. It was difficult for them to comprehend this

massive loss of life.

One-third of the French

army and

half of the Russian army were killed or

wounded in the long hours of fierce hand to hand fighting.

As horrible as it

sounds, oddly

enough, these massive losses favored the Russians. They

could replace the fallen soldiers; the French could not.

The relative strength of the two armies was getting closer.

|

|

|

Missed Opportunity

This had been

exactly the chance Napoleon had been waiting for. He typically

routed his opponents in these open field battles, but not

today. The battle was a stand off at best.

Napoleon

had been astonished by the bravery of the Russians.

Defending their homeland, the untrained and poorly

armed Russian army had fought with a ferocity that

won Napoleon's grudging approval. These were

the same people Napoleon had once described as

"ignorant, apathetic and blind". Not today.

Today the Russian soldiers had put up one hell of a

fight.

"The

most terrible of all my battles was the one

before Moscow. The French showed themselves to

be worthy of victory, but the Russians showed

themselves worthy of being invincible."

At the end of

the day, the French held the field, but Napoleon didn't feel

victorious.

He was actually dazed himself.

Perhaps

that explains why Napoleon had been

uncharacteristically cautious at this battle.

He had missed the perfect opportunity to cripple the

enemy.

The battle ended with the Russian Army

badly out of position. Their men had fought with

amazing courage, but as usual the tactical skill of the

French had out-maneuvered them. At the very end of the day,

the Russian lines broke and the men ran.

|

|

Ordinarily Napoleon would have

seized this chance to begin the forced pursuit that had

marked the campaigns he had conducted in the past.

However the state of

exhaustion of the French forces made Napoleon hesitate to

send them in pursuit.

|

However, he had

another option. Napoleon's vaunted Imperial Guard was rested and available.

Here Napoleon hesitated as well. He was unsure of

the Russian Army's position. Napoleon worried he might

be sending his most valuable men into a trap.

Normally

Napoleon never hesitated to take a chance if the stakes were

important. But today he blinked. By refusing to

set loose his elite

fighting force, Napoleon lost his singular chance to destroy

the Russian army.

Napoleon did not

know it, but this had been his last chance to save his army.

Napoleon was very grim after this battle. The Russian

army had escaped. It would live to

fight another day.

Meanwhile, although the

French had failed to deliver a fatal knockout punch, the Russians

were despondent. They had failed in their holy mission to

defend Moscow.

At the end of

the day, thousands were dead and no one was happy.

Such is the nature of warfare.

|

|

In the Russian camp,

Kutuzov knew his army had been lucky to escape.

Kutuzov understood why

Alexander had ordered him to fight, but he also knew that it had

been a great risk. Very few armies had ever survived a head to

head, open field battle with the French.

Although his troops were

miserable at their failure to stop Napoleon, Kutuzov was proud of

them. They had given the superior French force quite a

beating. Very few soldiers could ever make that claim.

However, now it was obvious to

Kutuzov the Russians did not have the strength to prevent the

French from marching onto Moscow.

The city was only 70

miles away. The Russians could not regroup in time to

find an adequate defensive position.

|

|

The only other

possibility was a last-ditch effort at the walls of Moscow.

However there were no defensive positions prepared. Kutuzov worried

that Alexander would panic and order a hopeless battle.

Kutuzov shook his head in disapproval. No point in losing

lives needlessly.

This defense would not

only likely fail, but it held the real

danger of trapping the Russian army with no escape route.

After a conference at the village of Fili,

Kutuzov fell back on the strategy of his predecessor

Barclay: Withdraw in order to save

the Russian army as long as possible.

It wasn't an easy

decision.

It came at the stiff

price of losing Moscow to the hated enemy.

The Russians had failed. Morale was

at an all-time low.

|

Napoleon realized the path to Moscow was now unblocked.

One week later,

Napoleon rode to the Poklonnaya Hill

about 2 miles from Moscow. There he stopped and

appreciated the splendid view.

He saw Moscow with the numerous domes of churches glaring in

the bright sun and crowned by the fantastic Kremlin,

majestic in its unique beauty. This ancient capital of

Russia had never been conquered. That was about to

end.

After all the

death and suffering, the moment Napoleon and his marshals

had been waiting for such a long time had finally come.

The men were excited. At last!

It had been a

costly campaign. They had crossed the Nieman River

three months earlier with 600,000 men. Now their

numbers had dwindled to half that total thanks to bloody

Borodino, Cossack raids and the

merciless starvation strategy.

Napoleon wasn't

at all happy about the huge losses. Nevertheless he quietly congratulated himself. His brave

gamble at Smolensk a month earlier had paid off. As he

prepared to take possession of the spiritual capital of

Russia, surely now the end was in his grasp.

|

|

|

|

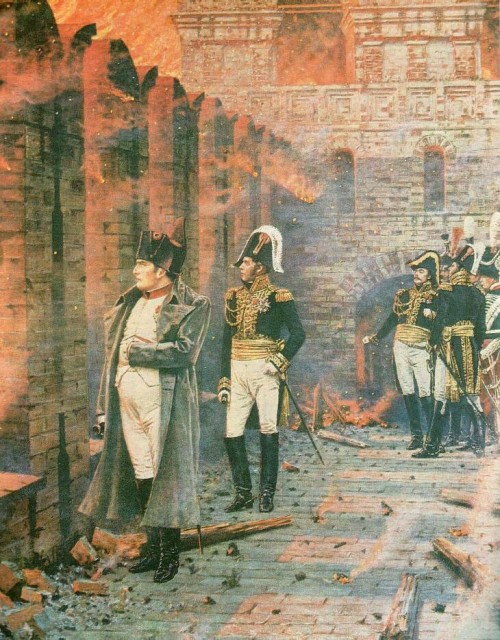

Napoleon Enters Moscow

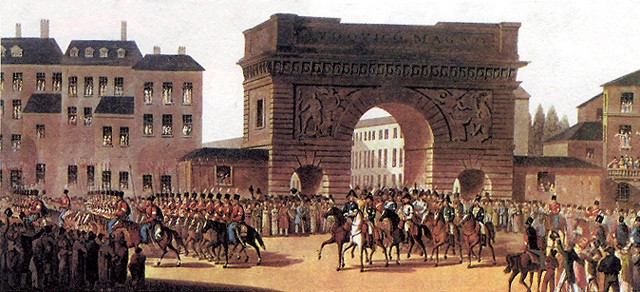

On September 14

at 2 pm Napoleon rode to the Dorogomilovskaya gate and

stopped. He was sure the gates would open and he would be met with

a deputation from Moscow entreating him to spare their

city.

Nobody came out

to greet him. This was odd.

Ordinarily a delegation would greet them and offer proper

housing and food. They would fall at his feet and pray

that he would not hurt anyone

or destroy their city. But not this time.

Napoleon was

secretly disappointed by the lack of custom. He felt it

robbed him of a traditional victory over the Russians after taking

this historically significant city. Who could

possibly understand these uncivilized Russians?

Napoleon hesitated. Fearing it was a trap like the

Trojan Horse,

Napoleon ordered men to go inside and look around. After some time

the officers rode back and reported Moscow was empty.

Napoleon was aghast.

"Moscow

deserted?" Napoleon shouted. "Impossible! Go find

where those coward boyars are hiding and bring them to me!"

But there were

no boyars. All that was left were a handful of lunatics and

criminals who had been freed from asylums and jails by the

retreating Russians. They roamed freely through the streets

along with a handful of wretched poor people who had

lingered behind in search of valuables.

Napoleon gave the order that the men were free to explore

the city and look for food. This was the start of a

day of joyful plundering. The people of Moscow had

taken what they could carry, but many riches had been left

behind. Even better, they found enough food left

behind in the homes to finally enjoy a decent meal.

|

Napoleon could

have cared less that his men were celebrating. He was

deeply

disturbed by

this latest development. The hunger

of his troops caused by the fanatical scorched-earth

strategy of the Russians had unnerved him. Now this

deserted ghost town had left him baffled. What exactly

was the Russian strategy trying to accomplish?

If this was Paris, blood would be flowing in the streets as

the French fought dearly for every niche and corner.

Who hands over their most important city without a struggle?

Napoleon

shrugged. More than

likely Alexander's representatives would come to town the

next day bringing the peace offer. Still, there was

something definitely eerie about this empty city.

The following

day, Napoleon

himself decided to enter. He wandered around aimlessly. Sure enough, all but

a few thousand of the city's 275,000 people were gone.

Moscow had been turned into a ghost town.

Napoleon

rolled his eyes. What were these crazy Russians thinking?

His first orders were to to restore discipline. After 24

hours of plundering Moscow, it was time for the troops to

settle down.

His headquarters were in the Kremlin. Napoleon knew what the

Kremlin meant for Russians. For several hours the emperor

was happy and proud - he was in Moscow, in the Kremlin, in

the palace of the tsars! He thought that the aim of the

campaign was achieved. Here in the magnificent Kremlin, he would

soon sign a

peace treaty with the Russian Emperor on his own conditions.

Napoleon was satisfied at last.

|

The

Burning of Moscow

|

Napoleon retired to a house on the

outskirts of the city for the night, but two hours after

midnight he was awakened. Duroc and

Caulaincourt, his aides, informed

him that a fire had broken out in the city.

As Napoleon rushed to his window, more men brought in

strange reports telling of Russians starting the

fires and stoking the flames.

Alarmed,

Napoleon went

back into town

to the Kremlin. From a safe

distance, he watched the flames continue to grow.

He exclaimed, "What savages! To

annoy me they burn their own history, the works of

centuries!"

Moscow was built

completely of wood taken from the nearby forests. The

fire took hold quickly. The brisk

wind raised huge tongues

of flame to the sky.

Burning

buildings crackled, then tumbled in great protest to the

ground. Shafts of sparks fell

throughout the city

like rain. Unchecked, this fire threatened to destroy this

entire ancient Russian

holy place. But there was little

the French could do to stop the inferno. All the

efforts to put out the fire were without any results.

The heat forced the soldiers to

retreat.

All they could

do was watch. The horror of

fire overwhelmed the French. This was so senseless.

All those beautiful buildings being destroyed! Against

the firelit background, the men could see the smoky

silhouettes of Spasskaya Tower of the Kremlin and the

domes of the St. Basil Cathedral.

Something was on

fire on the Red Square. And behind the St. Basil

Cathedral the view looked like a huge terrible bloody

curtain from the ground to the sky. The Zamoskvorechie,

a Moscow suburb, was completely on fire.

Napoleon shook

his head in continued disbelief. He was hypnotized.

Rich mansions with invaluable works of arts and exquisite

churches perished.

"These

Russians are barbarians! To burn one's city is

insanity. They conduct this bizarre war of extermination.

A demon must possess these people!"

|

|

|

Suddenly a fire broke out within

the Kremlin itself. A

Russian military policeman turned

arsonist was caught and

immediately executed.

With the firestorm spreading

in the Kremlin,

Napoleon could see they needed to

leave quickly or face real danger. They left the

Kremlin and went on foot to Arbat Street.

From there

Napoleon and his entourage were forced to flee down

burning streets back towards

Moscow's outskirts.

The burning

streets turned Moscow into something like a

labyrinth of fire. The French took a wrong turn.

As they retraced their steps, they realized one more mistake

like that and they could easily get lost and perish there.

Now the heat

grew so intense they had trouble breathing.

The group of

men began to run for their lives and

narrowly avoided being asphyxiated.

From the

outskirts of the city, they took a vantage point that

allowed them to safely watch the city burn. Napoleon

wondered if

Alexander had a similar vantage point not too far way.

By the time

the flames died down three days later, more than two-thirds

of the city was destroyed.

|

Who Ordered Moscow to Burn?

There is

controversy as to who burned Moscow and why.

Leo Tolstoy, in his classic novel

War and Peace, suggested that

the fire was not deliberately set.

Tolstoy believed it was

all an

accident. Tolstoy

blamed careless French soldiers.

|

Tolstoy's theory

made sense.

Considering how cold the

soldiers were, they surely

made bonfires in a

desperate attempt to escape the bitter Russian winter cold.

Perhaps one unit allowed their fire to get out of control

and didn't have an effective way to stop the burning from

spreading.

Contradicting

Tolstoy's theory, there is a great deal of circumstantial

evidence to suggest Count Rostopchin, the mayor of Moscow, gave orders to have

the Kremlin and major public buildings blown up and

set on fire.

Supposedly Rostopchin had

pleaded with Kutuzov to make a last-ditch stand at the walls

of Moscow. However Kutuzov thought the battle could

backfire and demurred.

Crushed,

Rostopchin then decided the scorched earth policy should be

invoked. He made preparations to have anything that might

have value for the French - food stores, granaries,

warehouses, and cloth stores - to be torched once the city

was evacuated by the Russians. According to the mayor,

his men waited till night, then set fire to the city.

|

|

There's only one problem.

Rostopchin himself denied giving this order and Rostopchin's

alleged role in the burning has never been completely

confirmed.

The best case

against Rostopchin rests with

the

memoirs of General Armand de Caulaincourt, Napoleon's aide

de camp. Caulaincourt's famous memoir, "With Napoleon

in Russia" was lost for years and finally unearthed after

World War I. It was finally published for the first time in

1933. Here is the

account as it appears in

Wikipedia.

Caulaincourt,

Napoleon's aide de camp, stated that they had been in

Moscow for three days. That evening a small

fire had broken out but was extinguished and 'attributed

to the carelessness of the troops'. Later that evening Coulaincourt was woken by his valet with the news that

'for three quarters of an hour the city has been in

flames'. Fires continued to break out in multiple

separate points.

Incendiarists were arrested and interrogated and

declared that their commanding officer had ordered them

to burn everything. 'Houses had been designated to this

end.' Later on in the same chapter he asserts 'The

existence of inflammable fuses, all made in the same

fashion and placed in different public and private

buildings, is a fact of which I, as many others, had

personal evidence. I saw the fuses on the spot and many

were taken to the Emperor.'

He

goes on to write 'The examination of the police

rank-and-file… all proved that the fire had been

prepared and executed by order of Count Rostopchin'.

Note that Coulaincourt's memoirs did not even appear till

1933, 121 years after Moscow burned. Rostopchin was

blamed for his role in the fire right from the start by a

lot more people than Napoleon's aide de camp.

Mayor Rostopchin was hated

in Russia because everyone in the country believed he was

responsible for burning the city. However, it is

important to note that Mayor Rostopchin spent the rest of

his life denying his role.

Here is

history's best guess. Common sense points to

deliberate sabotage by the Russians. As Caulaincourt

pointed out, "Fires

continued to break out in multiple separate points".

That suggests several men acting in unison. This

explains why the Russians were suspicious of Rostopchin.

Certainly

Tsar Alexander didn't order the burning. He is said to

have wept bitterly at the news. There is no record

that Kutuzov ordered it either. If anyone actually did

order the burning, it was probably Rostopchin. No one

else had the authority.

It is said that Rostopchin was treated bitterly

throughout the rest of his life for his role

in setting the fire. This makes no sense.

Yes,

the burning of Moscow was a supreme sacrifice, but it was a

brilliant sacrifice nonetheless. The burning of Moscow

placed Napoleon in a serious predicament that led directly

to his humiliating Winter Retreat. The burning of

Moscow had transformed the city from a precious bargaining

chip into a trap that would soon vanquish the monster.

Considering the

outcome, you would assume the person who ordered the fire

would go down in history as one of Mother Russia's greatest

heroes.

We may never

know whether the Moscow fire was deliberate or accidental,

but no one can deny its effect on the French army was absolutely crippling.

Whether anyone in the French Army knew it or not, from

this point on they were all doomed.

|

| |

|

The Grim Reaper

Comes Calling

Moscow had been the

best chance for the soldiers to find provisions. Now it was gone.

After the fire, not even a

crumb of bread was left. The fire had removed any chance of

finding food.

The fire left enough buildings left to provide shelter.

But it was cold. The Russian winter was setting in and it was

no ordinary winter. By some cruel fate, it was the worst winter of

the century.

How strange

it was that whenever somebody invaded Russia, the winter that

particular year was especially

savage.

The mystics claim that

in Russia, the Gods of the Russian winter exact their own revenge on

invaders. Perhaps it was these same Gods who burned Moscow...

|

Apparently these terrible winters had happened before. During

the invasions of Swedes and Germans, the winter was also very

savage. There was a story of the 6000 Swedes who died overnight

frozen right in their saddles during 17th century.

Now the Russian Winter

enveloped the French Army. The bitter cold caused

intense suffering. There was absolutely nothing to eat.

Meanwhile Cossack raids 300 miles away

prevented new provisions to be delivered to the troops from supply trains.

The French were even getting low on ammunition.

Kutuzov's

patrols prevented the French from foraging. Every time the

French ventured too far from the walls, a Cossack patrol or snipers

were sure to

inflict casualties. The French were caught in a death trap.

No food, no gun powder,

no shelter, no wine... nothing. The soldiers started eating

dogs, rats and cats. Then they moved on to the horses. Thanks

to the dark magic of Russian winter, the Grim Reaper set up

permanent shop in the French encampment.

|

Le Grand

Trap

In chess, there is a

move known as a "Sacrifice". What you do is give up a valuable

piece in order to put your opponent in a tougher position. The

loss of Moscow was the ultimate sacrifice. And yet it was the

perfect sacrifice.

Napoleon had taken Moscow for two reasons. One, to find food.

Two, to use Moscow as a bargaining chip to force Alexander to

negotiate. Now, suddenly Napoleon had neither. His men

couldn't eat and he couldn't hold Moscow hostage because it was

gone.

Moscow had been

sacrificed to put Napoleon into the worst trap of his life. What was

he going to do now?

Ask yourself this

question. Would George Washington have been willing to burn down

Boston to trap the redcoats and end the war? If someone

promised him it would guarantee a victory against the

overwhelmingly superior English army, then probably yes.

|

Losing Moscow must

have hurt the Russians terribly, but it practically guaranteed

victory.

In fact, it was such a brilliant move that it is

shame no one knows who to give the credit to. Maybe Tolstoy

was right; maybe the fire really was an accident. After all,

no ordinary human being had both the guts and the authority to do

something this audacious.

Are you a believer in

mysticism? Maybe the unseen Gods that manipulate Fate lit

those fires. If so, you might wonder if this was the horrible

Karma of Napoleon catching up to him. If anyone ever

deserved a bad break, that would be Napoleon.

Strangely, Napoleon just

sat there on the outskirts of Moscow for a month. It was an

awful time for him. Most likely Napoleon spent all that time

pondering how he had ever gotten into this mess and wondering if

there was any way out.

No doubt

Napoleon kicked himself

for not turning back when he had the chance at Smolensk. Why did he

ever decide to march to Moscow?Napoleon shook his head.

Until Moscow burned, this move had made sense. When

he had first entered Moscow, Napoleon had every right to expect a fervent plea for peace from

Tsar Alexander I of Russia. However, the burning of Moscow

changed everything.

What use is a hostage if

the hostage dies?

Napoleon had to admit

that he had never seen this coming.

This Moscow stunt took the

cake. Had his enemies had outfoxed him with that fire or did

they just get lucky?

Who in their right mind burns their most

important city?

As Napoleon stared at

the burned shell of Moscow, he asked himself again why he ever come

to this hell hole in the first place.

The only effective benefit of

capturing Moscow was to add the conquest of the

center of Holy Russia to his resume.

But it had accomplished nothing but get a

lot of his men killed. Napoleon had not lost a single battle,

but here he was a sitting duck. This campaign was a complete

failure if Alexander refused to come to

the bargaining table.

But Alexander remained

silent. Maybe Napoleon had

underestimated Alexander. The old Alexander

of Tilsit was fearful and easily manipulated. The old

Alexander would have sued for peace after Borodino or the capture of Moscow.

But the new Alexander was someone who operated by some sort of extreme logic

that made no sense to Napoleon.

Napoleon's world was

characterized

by rulers who preferred to

sign pieces of paper to end a conflict. To

avoid needless death and destruction, perfumed royalty simply traded

territory with the stroke of a feather and ink.

Not these Russians.

These Russians had defied all civilized

logic of the day. Certainly

a leader might give up something small

to gain freedom, but no

one burns their capital to do it!!

That is too extreme, too big of a sacrifice.

Napoleon concluded it

took the mind of a fanatic to

burn a capital city. This was a decision born of lunacy, not

sound judgment.

Nor was it the work of a gentleman to burn

his

own crops, uproot his own people, devastate

his own capital and

refuse to do battle

while the people of his country suffered and died.

This strategy was not the work of a

gentleman, but rather the doings of a coward.

Napoleon shook his head

in disgust. Not for the first time Napoleon wondered if it was

the centuries of Mongol domination that had caused such insanity.

Someone had taught these people to think like barbarians!

Even their

leader had turned into a madman.

Napoleon's Plea

As the days passed, no

offer of peace appeared. So Napoleon wrote a letter.

"My lord Brother Alexander. Beautiful, magical Moscow exists no

more. How could you consign to destruction the loveliest city in the

world, a city that has taken hundreds of years to build?"

Alexander replied with a

short message. He said that

the burning of Moscow had "illuminated his soul".

Alexander refused to

negotiate with Napoleon.

|

As the days passed,

Napoleon became increasingly desperate. This was ridiculous!

By all conventions of war, his army had just taken Russia's capital

city and conquered Russia! Why did not Alexander beg him for

peace? Did Alexander not understand how deadly his army still

was?

Alexander was in no mood

to negotiate. Now that he had lost Moscow, he didn't care

about anything. Napoleon be damned. Let him occupy

Moscow just as long as wanted. Napoleon was at best a prisoner

in the same city he had conquered. What more damage could

Napoleon do to Russia now?

Alexander hated Napoleon with a burning passion. Napoleon had

played him for a fool at Tilset. Let Napoleon burn in hell.

Alexander's silence

drove Napoleon nuts. The waiting was unbearable.

Napoleon had to do something. At last he decided to ask for

peace himself. He ordered General Lauriston to go to the

Russian headquarters and sue for peace. As Lauriston departed,

Napoleon is said to have shouted, "I

need peace! Get it for me at all costs!"

Kutuzov received

Lauriston, but shrugged his shoulders. "Your General has made war on

my country without provocation. I owe him nothing. If he wants

peace, tell him to leave my country and go home."

|

|

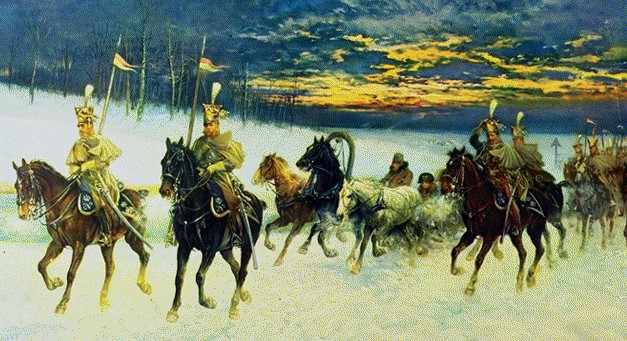

The Winter Retreat

|

|

Napoleon got the message. There would be no mercy given.

Napoleon had gotten himself into this mess. Now he would have

to get out of it.

After waiting a month

for the surrender that never came, Napoleon was forced to lead his

starving army out of the ruined city. He knew his men were in

serious danger. Napoleon had one hope. If he could break

through Kutuzov's blockade and head south to the Ukraine, he would

probably be able to find food there and save his army.

The French left Moscow

on October 19 in the dead of Winter. The Russians knew the

French were on the move. Kutuzov sent a detachment to

intercept. A battle took place on October 24 at Maloyaroslavets.

They intercepted the French and

fierce fighting began. During the course of the engagement the

town changed hands no fewer than 8 times. The French had

'fought like lions'. As well they should. Their backs

were against the wall. Their very

survival depended on it.

Marshal Kutuzov arrived

and decided against a pitched battle with the Grand Army the next

day. He preferred to retire instead to a well-prepared line of

defense nearby at Kaluga.

|

The

French casualties were about 5,000 killed, while the Russians lost

6,000. But the French weren't celebrating. As usual, the

Russians had lost the battle, but continued to win the war. The French had won a tough victory on the day only to realize with

sinking hearts that their preferred path to the Ukraine through

Kaluga was far too well-defended.

The French had a choice.

They could attempt a bitter, deadly fight against the firmly

entrenched enemy at Kaluga or they could take another path that

would not require a fight.

Napoleon chose the

unopposed direction. However, he knew full well what Kutuzov

was doing. Kutuzov had just forced Napoleon to retreat through

Smolensk. This meant retracing the same ravaged 600 mile route

that he had taken to Moscow during the summer. Napoleon had

desperately hoped to avoid this route. He knew full well there was

not a single drop of food to be had in this direction.

|

|

|

The Cold

Cruel Russian Winter

The Death March had

begun.

During the disastrous

retreat, Napoleon's army suffered continual harassment from the

merciless Russian army.

The conditions were

unbelievably harsh. Shelter was rarely found. Stalked by

subzero temperatures, hunger, and the deadly lances of the Cossacks,

the decimated army limped along.

The agony the French

suffered must have been unbearable. Still, they had shown no

mercy when they held the upper hand.

|

|

There was certainly no reason for

the Russians to behave any differently.

Throughout the Death March, the Russians never

let up. They inflicted further defeats on the

Grande Armée at Vyazma, Krasnoi, and Polotsk.

The French were

so low on supplies they were afraid to shoot back unless they had

someone directly in their gunsight.

You can't imagine it

could possibly get worse, but it did. Disease struck the army.

Soldiers began to desert for fear of getting sick. The

Cossacks on horseback would see their tracks in the snow,

track them down and execute them.

|

Horses died right and

left. They became instant meals. Sometimes the men ate

horsemeat raw if they were hungry enough.

The cruel Gods of the

Russian Winter had one more horrible trick up their sleeve. When

the Retreat began, it was too cold at first. The

French endured a

bone-chilling frost that few had experienced before.

The cold was utterly agonizing. The temperatures were known to drop to 20

degrees below zero.

First to die were the weak.

Too

exhausted to walk, they collapsed and died.

As the little food supplies

they had ran out, the strong got weaker and they too began to die.

Men would just drop all

day long. Their corpses lined the road. The bodies

stayed right where they fell until spring.

|

|

Once

again the weather played another evil trick.

Impossibly, this time it got even

colder than before. One bitter night a

thousand men were said to have died in their sleep overcome

by exhaustion, exposure

and misery.

But then the weather

mysteriously changed. There was a warm spell which thawed the

frozen roads — slowing down the march even more. It

was actually easier to travel on the roads in winter because the

surface was hard. Now that the snow melted, the

heavily rutted

roads became quagmires

of mud. Every problem the French had

encountered on the way to Moscow they had to face again on the

retreat.

Streams that were once frozen

and easy to cross became difficult to

cross. If the waters had to be waded, imagine how cold and miserable the men were

in their wet clothes after crossing. Men died simply from

crossing a stream. Unable to dry off, they began to shiver in

the unrelenting cold so hard they couldn't even continue walking.

|

Berezina River

All the bridges

had been destroyed the previous summer. The

warming trend meant rivers that could have been crossed on ice

now needed bridges.

One such river was the

Berezina.

The

Berezina

River was not far from the border with French-occupied Lithuania.

The Berezina was the last river the French had to cross to

get to safety.

Napoleon's plan was to cross the

river and head for Poland. The Russians thought otherwise. This was a great spot

to trap his army and destroy

it.

The recent thaw worked

greatly to the Russian's advantage. The warm weather ruined

Napoleon's original plan to

cross the frozen river while it was iced over.

|

|

|

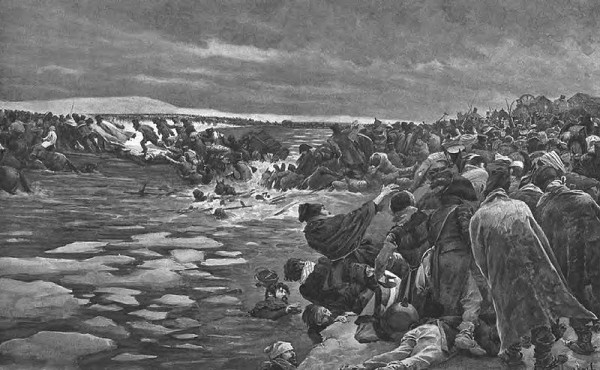

In late November, Napoleon's engineers did their best to create a

temporary crossing at the Berezina.

Over a four day period, Napoleon struggled to get his men across.

Then the Russians showed

up. The soldiers

waiting to cross panicked when they were

attacked by the Russians. In their

desperate attempt to cross the bridge, it

broke. Many tried to wade cross the

semi-frozen river only to die of frostbite later.

The rear guard suffered

terrible losses trying to provide cover for the desperate men.

An estimated 25,000

soldiers died or were captured. It was a

crushing final blow.

Since then "Bérézina" has

become used in French as a synonym for

"disaster". Or "catastrophe" if you prefer.

It was over.

Napoleon's Winter Death March had come to its final bitter conclusion.

|

| |

|

The Death

Toll

|

By the time the army crossed into Poland in early December,

somewhere between 95,000

and 110,000 exhausted, tattered

soldiers were all that remained of the

600,000 proud

soldiers who had crossed the Nieman

River five

months before.

Out of those 100,000 men

who managed to cross the Berezina River in November, only 27,000 of

those soldiers were still fit to fight.

380,000 men were dead or missing and

100,000 were captured.

All told, the French

lost about 400,000 men with most casualties occurring on the way

home. The Russians lost 200,000. Of course, that doesn't

include the massive loss of life among the Russian civilians.

Please keep in mind that

all these numbers are just someone's best guess. Records were

very imprecise back in those days.

One of the curiosities

of the Russian Campaign is that Napoleon's invasion of Russia marked

one of the few times when he had actually attacked with a larger force.

Napoleon had won most of his previous famous victories despite being

outnumbered.

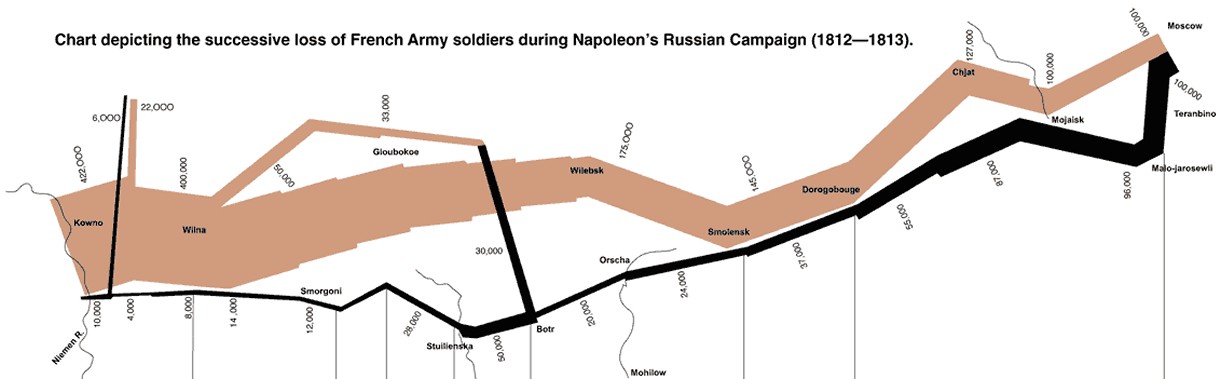

Charles Joseph Minard

was a French civil engineer in the 1800s. He drew up a fascinating chart

which depicted the massive loss of French lives in a very unusual

way. If you can bear to look, Minard expressed

the French losses by using a narrowing line.

|

|

|

Napoleon's

Comeback

|

Readers who are

unfamiliar with the saga of Napoleon will be shocked to discover

that the Corsican gangster would continue to wreak death and

destruction across Europe for three more years.

For an ordinary person,

Russia should have been the final straw. Out of an original force of 600,000, only