Saint

Petersburg

Written by Rick Archer

February 2012

|

Bitter

Disappointment

The founding of Saint Petersburg must be

considered one of Peter's greatest accomplishments. However,

Peter would first have to taste the bitter pill of an ignominious

defeat. Even worse, Peter's failed gamble would bring Russia to the very abyss of ruin.

Only a lucky break saved

Russia from destruction. As Peter wept with anguish, little

did he know there was a silver lining in the darkness. As fate

would have it, Peter's defeat contained the seeds that led to the creation of

Saint Petersburg. This is the story.

|

|

|

|

The Great

Northern War

On his return to Russia

from his European adventure, Peter found himself obsessed with the

dream of obtaining a maritime outlet. Peter's trip to England

had convinced him more than ever of the value of sea power.

Peter had learned first-hand how naval power had made England a

mighty nation. He was certain that what his country required to move

forward was an access route to the seas. Sea access would be

so valuable to Russia.

Peter preferred the

Black Sea. Unfortunately, he had

failed in one of his main objectives. During his trip to

Europe, Peter had found no allies against the Turks among the

Western powers. Realizing Russia couldn’t fight Turkey alone,

Peter begrudgingly gave up his dream of a Black Sea access.

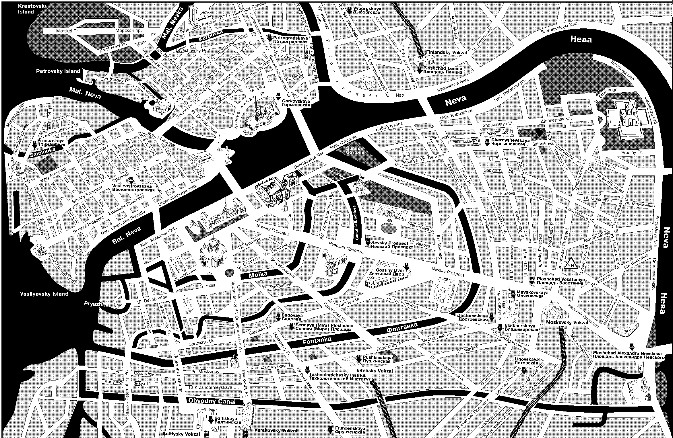

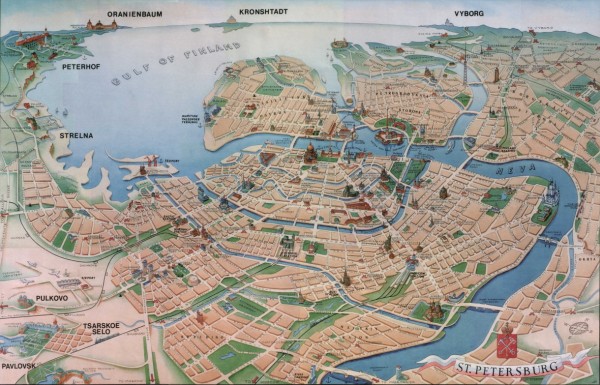

Instead, he turned his

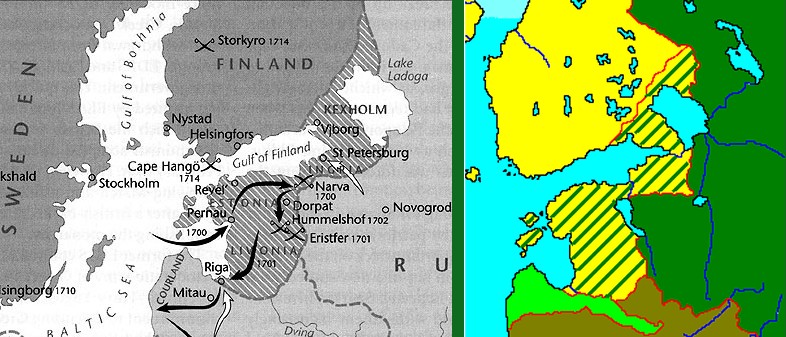

attention to the Baltic Sea. As you can see from the map, Russia was completely cut off from even a single port. Russia could not hope to

obtain her share of the trade and commerce of the world without a port.

Possession of an ice-free port was

critical to her economic development.

At this time, Russia’s

route to the Baltic coast was blocked by powerful Sweden.

Sweden had pried away much Russian territory in the past hundred

years due to

Russia's military weakness during the Time of Troubles.

|

Gustav Adophus was the

brilliant leader who started Sweden's surge. However, he had

died in 1632 at the end of the Thirty Years War. He was succeeded by

an equally adept leader in Charles X who continued his father's

expansion. Sweden reached its largest territorial extent in 1658

under the rule of Charles X. At the end of the 17th century

Sweden was the third largest country in Europe, surpassed only by

Russia and Spain. Sweden was the dominant power in the

region by a significant margin.

Russia may have been

huge in size and population, but that meant little. Its people were

servile, sullen and uneducated. There was almost no spirit of

nationalism. Furthermore, thanks to a century of weak

leadership, its military had little tradition. There was no

military academy and few qualified officers. Consequently the military was untrained and poorly organized.

Its commanders were all foreigners who weren't good enough to get a

job in their own country.

Peter knew all this.

Russia had a lot of catching up to do if it wanted to challenge

Swedish supremacy. Since Peter didn't think he

could conquer Sweden on his own, to dislodge

the Swedes, Peter allied himself to a three-way coalition: Russia,

Denmark and Saxony-Poland.

All three states

carried a grudge. They had each lost significant territory to the Swedes and their

brilliant leader Gustav Adophus throughout the 1600s.

Now they wanted it back and more.

Each country had

an agenda. Denmark's Charles V wanted to regain Scania

and other territories on the Swedish mainland lost in 1658.

Augustus II of Saxony-Poland wanted Livonia back (lost in

1629) to put an end once and for

all to Swedish economic predominance in the Baltic.

He

wanted to develop Poland's industrial base by using Poland's

raw materials and Saxony's economic know-how. However, he

could not do this while Sweden remained a commercial rival

in the Baltic.

Peter the Great simply wanted a foothold in the Baltic Sea. Russia could never be

great in the Baltic while Sweden was pre-eminent.

Sweden possessed three territories - Karelia, Ingria

and Estonia (see map) - that completely blocked

Russia's advance to the west.

The coalition

saw an opening when a fifteen year old king - Charles XII -

took the throne in 1697. They figured this kid would

be an soft target. They also had a shared belief that Sweden

was a spent force by the 1690s. This was the time when

Sweden's territory was vulnerable to be cut up by a superior

force.

Now was the time to attack.

|

|

The

Battle of Narva

The story of the

Great Northern War can be summed up from the Russian point

of view as the Tale of Two Battles.

The war started

badly for the Alliance. The Denmark and Poland-Saxony opened hostilities in

April 1700, striking at Sweden from several directions at

once.

Moving to meet

the threats, 18-year old King Charles XII of Sweden elected

to deal with Denmark first. Leading a well-equipped and

highly trained army, Charles launched a bold invasion of

Zealand, the Danish island where Copenhagen is situated.

The Danes folded

fast. This campaign forced the Danes out of the war

right at the start. That left the Swedes with Poland

to deal with.

Russia was not in the war right at the start.

Peter did

not dare make war on Sweden until

his peace with the Turks was secure.

The Russian army was far too weak to fight two fronts at

once. While Sweden took on Denmark and Poland, Peter

swore to the Swedes that Russia had no intention of joining

the fight.

That was a

complete lie.

|

|

Peter had

targeted the city of Narva (see map) as his main objective. Narva

would give him the port on the Baltic that he so craved.

Narva had once been under Russian control from 1558 to 1581,

but Sweden had ripped it away when Russia entered its "Time

of Troubles". Peter wanted it back.

Narva was the nearest Baltic port to Russian

territory which made it supremely valuable to Peter.

Narva rested at the junction of the Gulf of Finland and the

Narva River which drained massive Lake Peipus

(see map), Europe's fifth largest lake. Access to

Narva would allow Russia to ship goods to the Baltic from as

far away as 200 miles using the Velikaya River.

Peter was quite

familiar with this area. Lake Peipus was where he had

learned to sail as a young boy, so he was well aware of

Narva's value. Peter figured that with Charles

distracted far away by Denmark and Poland, he could seize control

of Narva before Charles could possibly react.

Peter delayed

his attack till the dead of winter. By attacking in

November, he figured the weather would work to his

advantage. His forces only had to travel 50

miles while the Swedes would have to travel a considerable

distance to defend this valuable possession.

There was no

conceivable way the Swedes would ever be able to react fast

enough. Narva was easy

pickings.

Arriving at Narva in early November, Russian forces began

laying siege to the Swedish garrison defended by 2,500 men.

The Swedes were badly outnumbered. With

35,000 men, the Russian force was much larger.

|

Peter was supremely

confident. How hard could

this be? By the time the

Swedes came to the defense of Narva, Peter would already have his port.

Peter's timing wasn't as

good as he thought it was. After concluding business with

Denmark, Charles embarked across the Baltic with 8,000 men for Livonia in October with

the intention of driving the invading Polish-Saxon army from the

province. Landing in Livonia

(modern day Latvia), Charles noticed that the

Polish-Saxon army was now encamped for the winter.

Seeing that the Poles

were in hibernation, Charles decided instead to move east to aid the

city of Narva which had just come under siege by Tsar Peter's Russian army

three weeks earlier.

Narva was only 150 miles away.

Charles was there in a matter of days. The Swedes arrived

outside the city on November 29. It was a fortuitous break for

Sweden which caught the Russians completely caught

off guard.

Even though the Russians

still out-numbered the Swedish army by 3 to 1 (35,000 to 10,500), the Swedes were a fighting machine taking on an

inexperienced army with mediocre equipment. The Russian army

had not yet been fully modernized by the tsar.

What was supposed to be

an easy cherry picking romp had turned into a deadly threat. Peter's

luck could not have been worse... but then it did get worse!

Upon the surprise landing of the Swedes,

Peter decided he needed to head to Russia immediately and bring back reinforcements to meet the

increased Swedish threat.

Peter gambled that he had a couple days

to round up more troops. He never expected Charles would instantly go on attack.

But that was exactly what Charles did.

Charles attacked one day after landing.

On the morning of November 30, a blizzard

descended. Despite the foul weather, the

Swedes still prepared for battle. Meanwhile Croy,

Peter's stand-in, invited the majority of his senior officers

to a warm sit-down dinner.

Around midday, the wind shifted to the south, blowing the snow

directly into the Russians' eyes. Spotting

the advantage, Charles began advancing against the Russian center.

Using the

blinding snow as cover, the Swedes

were able to approach to within 50 yards of the Russian lines

without being spotted.

Surging forward, the

Swedes quickly forced the surrender of the

Russian center and captured Croy, the Russian commander.

|

|

The remaining Russians tried to retreat and

regroup, but the weight of the panicking Russian forces led

to the collapse of a temporary pontoon bridge over the Narva River.

Their

escape route was destroyed. In an instant, the bulk of the army

was trapped. It was either jump into the

frozen waters of the river or fight to the death. White-faced,

the Russians turned back to look at the oncoming Swedes.

Seeing what happened and

seeing the look on the doomed men's faces, the Swedes stopped in

their tracks. The situation was so hopeless that the Swedish

actually started laughing at the helpless Russians.

One of the Swedes made a

suggestion. Did the Russians wish to surrender or did they

prefer to die? Humiliated, the Russians surrendered on the

spot.

|

It was over.

20,000 men

had just been captured! Only 5,000 men were able to escape

back to Russia.

The

Battle of Narva was a stunning

victory for the Swedes against overwhelming odds.

Furthermore, this wasn't any ordinary defeat. It was a

thrashing of historic dimensions.

Indeed, the defeat was

so thorough it should have ended Russia's involvement in the

Alliance uprising once and for all.

In the fighting, Sweden lost 600

killed and 1,200 wounded. Russian losses were approximately

10,000 killed and 20,000 captured.

Just think about it for

a moment. How can any commander allow 20,000 men to be

captured? The level of incompetence involved was more than the

imagination can even grasp.

|

|

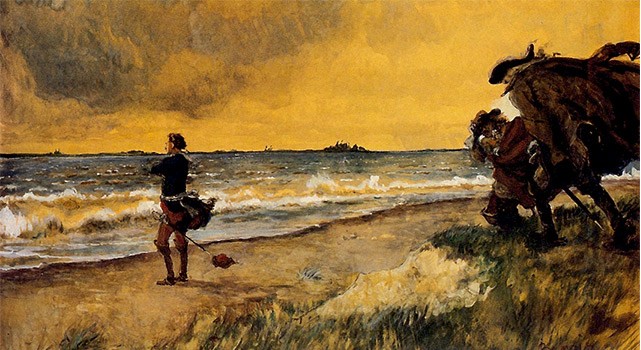

This famous

picture of the battle shows the Swedish Army disarming

the 20,000

Russians.

In addition to the

captured muskets,

the Swedes captured all of Croy's

artillery, supplies, and equipment.

The Russian army

was so severely decimated that Sweden now had an open field to

invade Russia.

Charles could march into Russia to destroy what was left of

the defenseless, disorganized ragtag enemy.

However, Charles did not pursue the Russian army. Charles was so

disdainful of the pitiful fight put up by the incompetent Russians

that he decided to move first against Poland, the more dangerous

opponent.

Charles had missed his

chance. By ignoring Russia when he had a sure-fire kill shot,

Charles had just given Russia the break it needed to live for

another day. That which doesn't kill you makes you stronger.

Charles would

one day regret his decision. Had he chosen

differently, the Swedish Empire might stretch all the way through to

Siberia today.

Think about that

for a moment. There was no army capable of stopping

Charles all the way to the Pacific.

|

|

Out

of the Ashes

Peter was

devastated at the news. Imagine being informed that

you have just lost practically his entire army and all of

his equipment!

This wasn't just

Pearl Harbor. This was much much worse!

Furthermore, unlike Pearl Harbor, Peter was completely

responsible.

Peter went into

shock. How could this be possible?

In his wildest

imagination, Peter could not believe that his no-brainer attack on Narva

could have ended so disastrously. Peter had been so

confident that he and his staff didn't even consider the

most fundamental back-up contingencies and escape routes.

All in all, this defeat was a colossal, almost

incomprehensible disaster.

Peter's reckless

gamble had just left

his country's soft underbelly totally exposed to

counter-attack.

With the Swedes

literally at his doorstep, how could Peter possibly prevent Charles

from attacking Russian soil? Charles had most of his

men and all of his equipment! There was nothing between Narva and Moscow other than deep snow to stop Charles if he

so cared to press his advantage. If Charles moved as

fast on Russia as he had moved at Narva, he could be dining

at the Kremlin within a week.

Who knows why

Charles didn't move forward. One possibility was that

Charles did not realize the full extent of Russia's dilemma.

Did he not he realize there was no force left capable of

stopping the Swedes?

Perhaps the deep

snows concerned him. However the Swedish were no strangers to

snow. It hadn't stopped them at Narva.

Maybe

Charles worried there was no food to feed his

army in the cold of winter. However, it is unlikely that Peter

could have organized an effective food destruction effort

back in those days of slow communication. Charles

could easily have been deep into Russia territory before the

word even got out.

The likeliest

reason is that Charles assumed that Russia was decimated and

not worth the further effort. Like Denmark, Charles may have decided

that Russia had learned its lesson and would bother him no

further. Charles held the Russians in complete

contempt.

He thought the Russians were imbeciles.

They were nowhere near the threat posed by Augustus and his German army.

Charles definitely

did not want to leave a hostile German army at his rear

while pushing deep into Russia. Why not pursue Poland-Saxony,

by far the more

dangerous opponent, first?

Charles didn't

know Peter.

Peter seethed at

Russia's humiliation. Then it became personal. Peter discovered

that all of Europe was laughing at him too. His decision

to return to Russia on the eve of the attack looked to the

world like he had turned and run from a little boy at the first sign of

danger.

Peter bristled

at the world’s interpretation of his

departure from Narva the night before the battle. The victory for the Swedish Emperor brought him

enormous praise and the respect of Europe. On the

other side, the Battle of Narva made Peter look like a weak

monarch. Peter was labeled a coward and his army became a laughingstock.

Considering Peter's thin skin

and his need for European approval,

the world's contempt must have eaten at his soul.

|

Humbled by his

defeat, Peter knew he was lucky beyond his wildest

imagination to be given a second chance. He now set

himself to the task of repairing his tattered army.

Peter decided he

had blundered badly, but it would be an even worse blunder

not to take advantage of the second chance offered to him by

Charles' error in judgment.

With his army's weaknesses exposed, Peter

knew exactly where to start. He saw that his army was

extremely unequipped and undertrained. He set out

right away to remedy this problem with the help of his boyar Shermetev, who oversaw much of the army’s modernization.

Russia adopted European battle tactics and bought updated artillery pieces.

Most important, they

established a military academy in St. Petersburg to teach

young men how to properly run the new army.

Over the next

few years, the Swedish army was never far away.

The enemy was a mere 400 miles away fighting

Augustus in southern Poland. With the constant threat

of Swedish invasion looming over them, the Russians had a powerful incentive to work hard.

The safety of Mother Russia depended on it.

|

|

Nöteborg

and Nyen - The Comeback Begins

|

After his

devastating victory at Narva in 1700, Charles of Sweden had

decided to pursue his Polish enemies deep into Poland.

While licking his wounds, Peter took note that the

fortresses at Nöteborg

and Nyen (see map) at either end of the Neva River were

vulnerable to attack.

When the cat's

away, the mice will play. It was impossible for Sweden

to protect every part of its vast territory. Sweden

simply didn't have the manpower to sufficiently guard far

flung outposts like Nyen and Nöteborg.

It is important

to note that Finland was part of Sweden back in 1700.

However, its people were not particularly loyal to Sweden

and certainly not interested in dying by rushing to defend

Swedish outposts under attack.

The Swedes had

two strategies to defend their distant outposts.

First, they made their forts strong enough to

withstand enemy attack until reinforcements could come (that

had worked like a charm in Narva). Second, if the

fortress fell, they would send an army, take it back and punish the

aggressors.

|

|

|

Nöteborg

As the pain of Narva

receded into the background, Peter was determined not to

quit. In September 1702, Peter

took a great risk by going back on the offensive. It had only

been two years since the defeat in Narva, but Peter was driven by

his lust for revenge. His new target was a fort situated on an

island blocking the junction of the Neva River and Lake Ladoga.

Peter assembled a force of 12,000 and marched for ten days to Lake

Ladoga. There he laid siege to Nöteborg. It was a

reckless move because it invited the return of the superior

Swedish army. If things went poorly for the Russians, Charles

might decide to inflict severe punishment on his foes.

Just like Narva, the

siege stalled. In an act of defiance

eerily similar to Greece's Thermopylae and the Alamo saga of Texas, the commander bravely refused to surrender

even though the fort was guarded by only 400 men.

|

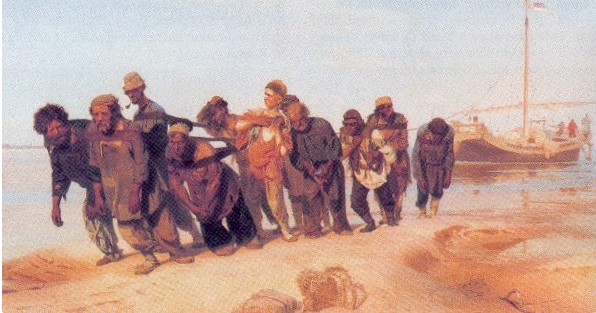

Peter ordered the Russians to bombard the fort.

In this picture of the Siege, Peter is easily identified because he

is the tallest person standing.

After two weeks of heavy

bombing from the banks of the Neva, Peter decided he had waited long

enough. He had to take this place before the reinforcements

showed up. If these people weren't going to give in, it was time

to storm the fortress.

The Swedes put up a

ferocious defense against the assault. Despite receiving hits from an estimated

6,500 cannonballs, their fortress was still intact. Utilizing the fort

to full advantage, the Swedes repulsed one wave of attack after another.

The Russians were so

discouraged they wanted to quit. In desperation, their leader told

the boats to leave. Now the Russians would either have to

fight or die. This did the trick. The tide turned.

After a brutal 13 hour

fight, the Swedish commander finally agreed to stop. Of the

original 400, 250 were still alive. The Russians, meanwhile,

had lost 600 men in the fighting and 300 more were wounded.

Considering the odds, it

was not exactly an impressive victory, but Peter had his fort.

|

|

|

Nyen

Next up was the fortress

at Nyen which lay a mere 30 miles away at the other end of the Neva River.

The Nienchanz fortress guarded the mouth of the Neva where it connected

to the Gulf of Finland.

|

The

Founding of Saint Petersburg

|

|

Unlike Nöteborg,

the Swedes didn't put up much of a struggle at Nienchanz.

After an 8-day siege, the Swedish garrison surrendered on

May 1, 1703.

At long last, Peter

had his cherished access to the sea. With Nyen under

control, Peter was determined not to lose this valuable

spot back to the Swedes.

To protect the newly conquered lands on the Neva delta,

Peter the Great needed a better fortress. The Nienchanz

fort was

no use. It was small

and badly damaged. Peter immediately began looking

for a different way to fortify the area.

Peter recalled how

difficult it had been to attack the island fortress of Nöteborg.

The water had acted like a giant moat. Peter chose Hare's Island

in the middle of the Neva to build the

Peter and Paul Fortress.

Peter pushed his

men to the limit. His greatest fear was that the

Swedes would return before he could adequately defend his

new prize.

On May 27, 1703,

the fortress was founded. No one knew it at the

time, but this day would come to be known as the

official birthday of Saint Petersburg.

|

During the frantic construction of his new fortress, Peter

became more and more intrigued with this area. He realized that existing ports like Narva

or Riga tended to be freer of ice in the winter. However to take

these cities by force would surely invite massive

retaliation by the Swedes. What if he built a seaport from the

ground up?

Peter looked around. This

desolate, barren area was scarcely populated. It consisted of little more than the ruined Nienchanz Fortress. There was a good reason why the area was

abandoned - these were vast swamplands known as the Neva Delta.

The Neva River drained a

vast Russian watershed into the Baltic Sea. During the rainy part of

every year, the whole region was flooded by water. There was

little solid ground available to build the fort, much less an actual

city.

|

|

Surely no one

would be stupid enough to build a city here.

Or would they?

|

In real estate

terms, this place did have one good thing going for it.

Location Location Location.

Peter took one look at the

Neva River and realized how easily this giant waterway could

someday be used to transport goods in and out of Russia's interior.

Then he looked at the vast Gulf of Finland and saw what a

fine port this spot would make. Peter made up

his mind.

The Neva would

become the Volga of western Russia. This new city would

become Peter's Window looking out to Europe.

When he told his

engineers of his plan, they blanched in terror. They

quickly exclaimed that it was sheer folly to be building on

mud and quicksand. Just in the brief time they had

been working on the new fortress they had already

encountered the infamous Neva floods.

|

|

|

Peter was

undeterred. Peter ignored the

criticism because he already knew it was possible to build a

floating city.

During his

European Tour a few years earlier, by chance Peter had

fallen in love with Amsterdam. Like St. Petersburg,

Amsterdam was built in a river delta area.

The Dutch

had brilliant engineers who knew just how to reclaim land

from the sea. With

60 miles of canals, 90 islands, and 1,500 bridges, this

Dutch city had become famous throughout Europe for its exquisite canal system.

Thanks to his

unforgettable experience in Europe five years earlier, Peter had

seen just the

model he needed.

He began to fashion his city in the

image of Amsterdam.

|

It was insanity enough to build a major city upon what

amounted to a floating base. It was even more insane to build

a city in such an exposed, vulnerable place in the middle of a major

war.

One swift attack from

the Swedes, a couple of torches in the right place, and the new city

would go up in flames. Peter lost a lot of sleep worrying

about that exact scenario. After all, his new fortress was

makeshift at best. It probably wouldn't stand up under attack.

Nonetheless, Peter’s opportunistic nature got the best of him. War or no

war, he was too impatient to wait. So with the war in progress, Peter

began to map out his new town.

Peter began a race against

time. It is said he suffered constant nightmares from fear

that Charles would come and rip it all away from him. He constantly upgraded the

construction of his Peter and Paul Fortress. The original clay walls and bastions of the fortress were

completed by the end of summer 1703 under Peter's careful

supervision.

|

|

|

True to his decisive character, Peter ordered thousands of

peasants brought to the area.

He ordered them to cover the swamp with

tons of earth brought in on boats.

Russia was not a modern

country. However, one thing it did have was plenty of dirt and

countless slave-labor serfs to dig it up and drag it in.

Saint Petersburg was

being built by nameless, hopeless people who received practically nothing in

return for their sacrifice. They worked because they were

whipped if they didn't.

The

builders of the fortress were mostly soldiers and peasants

who

worked in very primitive conditions. The climate was

very cold and damp. Even when they weren't being

rained on, they worked in soggy, sloppy mud.

They would shiver for

practically the entire day.

|

Good housing was nonexistent and food

was in very short

supply. Furthermore the mosquito-infested swamps

guaranteed disease. Back in those days, the role of the

mosquito in spreading disease was not known. However, people

did know that wherever there were swamps, there was a

danger of disease.

Sure enough, working from dawn to dusk, the

men died in great

numbers. Some died from disease; still others died from

overwork. Since the work never stopped, some

people simply died right where they worked due to

hunger, exhaustion and cold.

These

people were treated little better than slaves.

Peter never hesitated

due to the death rate. This place had too much

strategic importance. With the war looming in the background,

the fort and other defenses had to be

completed as soon as possible. Peter continued constructing the city despite the losses and extra expenditures.

Peter's obsessive attempt to

build on the swampy

land would eventually work out after years of work.

However, when one takes note of the countless

deaths, that

explains why St. Petersburg is sometimes called

"The city

built on bones". There are

said to be curses about the city.

Due to Peter's legacy

of extreme cruelty, some believe there might be some sort of dark karma hovering over the city.

As for the intense

suffering and the massive loss of life, concern for the

welfare of others had never been one of Peter's strengths. It is

unlikely he even noticed.

|

|

Meanwhile,

Peter's vision was taking place.

In a move eerily

similar to Dubai's creation of islands in the Persian Gulf

400 years later, Peter ordered vast amounts of earth brought

in to shore up all the little islands in the delta.

By filling in

gaps, many small islands were combined to make larger ones.

The main body of

the Neva was left alone, but the curves in the smaller

streams were straightened somewhat and given embankments.

As the islands were raised, these streams were turned into

narrow canals of standard width.

The design began

to take shape. Soon there were canals everywhere that

carved Saint Petersburg into several large islands and many

smaller ones.

This modern-day

map gives some idea of the scale of the accomplishment.

|

Danger

Charles XII, King of Sweden, was well aware of what was going on.

He knew about the fall of Nöteborg and Nyen. He knew

about the new city under construction as well.

He sent

several ships up the Gulf of Finland to check on the

progress. Each time the ships stayed just out of

cannon reach as they inspected the construction.

Just months after the groundbreaking came the attack Peter

was worried about. An army of 4,000

Swedes was spotted moving in from the north through Finland. Peter had done his homework.

He had a system of sentries posted to provide early warning.

At the first

opportunity, Peter had established a military academy at St.

Petersburg. In addition, he always kept a regiment of army soldiers encamped nearby.

Furthermore he had a National Guard of sorts consisting of

the men who supervised the serfs. Most

of the time these men were involved with building the city,

but they all knew how to use weapons. Peter made sure

his back-up army went through frequent

military drills "just in case".

The news of the advancing

Swedish force was straight out of Peter's nightmares.

On the spot, Peter assembled an army of

7,000 men to move against the Swedish menace. He led the

expedition himself. To his relief, his men checked the Swedish threat without much

trouble. Disappointed that their sneak attack had

no chance of success, the Swedes turned around at the first

opportunity.

Peter was still

worried. He

continued to

monitor enemy troop movements in

the area and naval activity in the Gulf of Finland.

Furthermore, while the city was under construction, Peter

was having new warships built on the other side of the river

|

Peter was done

attacking new territories. All he wanted out of this

war was a Baltic seaport.

Now that he had his prize, Peter intended to defend it

with every possible resource at his disposal. What he

lacked was a navy, so he went to work on building one right

on the spot.

Right across the

River Neva from the fortress, Peter constructed the fortified

Admiralty complex. This was a shipyard where

powerful ships of Russia's new Baltic Fleet were being built.

Many of these vessels would soon be involved in a series of naval

skirmishes with Sweden during the course of the Northern

War. From all accounts, Peter's new Russian Navy

acquitted itself well.

Charles

did

make one brief naval attack, but it too got nowhere. The

defenses were too strong. It soon

became apparent that Charles had waited too long. By

failing to attack during the infancy of the city, he had

given Peter enough time to make his pet project virtually

unassailable.

|

|

|

For its

first few years, the new city was

limited to a small town around the fortress. However,

the

work never stopped. Every year hundreds of tons of earth

were moved to

the location.

Slowly but surely the islands began to

rise safely well above sea

level. As the islands

were shaped and firmed up, more area became available for

new buildings.

Thanks to Peter's vision, this barren no

man's land went from a swampy, scarcely populated area to the

beginnings of a magnificent European-style city.

The finished product was

a thing of beauty.

By 1712, Saint Petersburg

was ready to become the magnificent new Russian capital.

|

After the city was completed,

in 1714 Peter ordered

the rich merchants and

intellectuals to move there from Moscow. Those who refused

risked getting out of favor with the emperor,

never a good idea (especially not with this emperor).

Most people

took the hint and followed

orders.

The nobles were

told to build on one side of the Neva River. Merchants

and artisans were told to build on the opposite side.

The new

residents of St. Petersburg were ordered to pay for the

building of avenues, parks, canals, embankments, bridges and

other projects. Huge government buildings, designed by

foreign architects, were constructed. Peter's grand

Winter Palace became the official residence of the monarchs.

Nobles were obliged to build homes in St. Petersburg and to

live in them most of the year. The more serfs

a noble owned, the bigger his home had to be.

Everyone was told to buy a boat. Overnight, the new

city turned into Europe's biggest yacht club.

|

|

|

Everybody was amazed

that Peter's architects had somehow managed to tame the waterlogged

Neva Delta. Gone were the swamps.

Gone were the muddy little islands that rose mere inches above water

level. Gone was the dirty, reeking water. Gone were the

mosquitoes.

The islands were high

enough to provide solid embankments that kept

the Neva in check no matter what the season.

With the erosion of the

riverbanks checked, the muddy water was a thing of the past.

Now the water began to resemble the sparkling pure blue lake water flowing

down from nearby Lake Ladoga.

The Neva

quickly became the central focus of the city. Dozens of small

winding streams had been shaped into graceful smooth channels.

The waterways were simply exquisite.

Everyone agreed the

canals of Saint

Petersburg compared favorably to Amsterdam. The second "Venice

of the North" had emerged.

|

End Game

|

Following the

destruction of the Russian army

at Narva in 1700, Charles of Sweden

controversially had elected to turn south into Poland-Lithuania rather

than attack into Russia. The young king

thereby missed a key opportunity to take

Russia out of the war.

Charles wandered all

over Livonia chasing Augustus of Poland-Saxony. After two

years of pursuit, in 1702 Charles finally cornered

and defeated the Polish king Augustus and his Saxon allies at the

Battle of Kliszow in southern Poland.

After the battle, Augustus fled to

Germany. Now Charles was forced to track him down again.

Charles finally caught up to Augustus again at Leipzig and Dresden

in 1706, beating the Polish-Saxon leader handily both times.

At that point, Augustus

surrendered and made peace on terms acceptable to Charles.

Only one problem - Charles had spent six years chasing Augustus

around Eastern Europe. That had given Russia six valuable

years to prepare its military for Round Two.

Charles was still angry

over Peter's impudent seizure of Nyen and Nöteborg.

Now it was time to teach the Russians another lesson. After crossing

Poland, early in

1708 the Swedes defeated a Russian force at Grodno. Crossing

the Niemann River, the Swedish army was now on Russian soil.

Peter and the retreating

Russians set fire to what they could. As the Swedes advanced across

sparsely populated Lithuania they had difficulty finding food for

themselves and adequate forage for their horses.

|

Charles settled in Minsk

for several months of rest. In the summer of 1708, the

fighting resumed. Charles won a major battle at Holowczyn. Charles

reportedly said he enjoyed this victory even more than Narva. It was

time to head to Moscow.

The Russians were now in

full retreat. Worse, they were feeling quite demoralized.

Holowczyn had been a rout. It

seemed like their six years of military build-up had accomplished

very little.

Peter grimly stuck to

his scorched earth policy. Anyone who gave or sold food to the

enemy, or knew of such an act and said nothing, was to be hanged.

Those villages from which food was given to the enemy were to be burned

to the ground.

Peter's strategy began

to work. The Swedes reached Tatarsk only to discover the

countryside between them and Smolensk was barren of whatever they

needed to survive.

Charles had one card left to play. He was waiting for a supply

train of several thousand carts plus reinforcements coming from

Riga. However, by mid-September the supply train and the reinforcements

from Riga had still not yet arrived for Charles. His army was

in trouble.

|

|

| |

|

|

Starvation

Without the

supply train, Charles and his men and horses faced

starvation.

Charles was deeply

worried. It was absurd that he had never lost a battle to the

Russian army, but now the Russian countryside was about to

accomplish what the military could not do.

In a situation eerily

similar to Napoleon's fate waiting 100 years in the future, Peter

was winning the war simply by making the food disappear.

With the approach of

winter and nothing but devastation waiting ahead on the road to Moscow, Charles

had to abandon his Moscow strategy for the time being. Charles

decided to turn south. He headed into the Ukraine which was

more densely populated and likely held supplies of food and fodder.

|

Now Charles got more bad

news. His lifeline, the supply wagon train from Riga, had been

intercepted by the Russians. An eight hour battle had been

fought to a stand-off, but many Swedes had fled back to Riga at the

end of the day. With his passage blocked, the Swedish commander had no choice but to

burn the supplies lest they fall into Russian hands.

Charles briefly got lucky. As

he suspected, there was food to be found in the Ukraine.

Bunkering down near Kiev, his men discovered adequate supplies.

However the winter fighting took a toll on the Swedes. Charles

lost 1,000 men in January and more in another

skirmish in February.

Many of his troops

suffered from frostbite. The army was down to 24,000.

Local grain supplies and cattle were sufficient, but gunpowder was

low, some of it having been damaged by the wet weather in February.

Even more maddening were

the Cossacks who had taken to sniping from the forests as his men

passed by. This tactic was also used by the Russians during

Napoleon's retreat. This raises the question that perhaps the

Russians of 1812 got their inspiration from Peter's campaign.

|

|

The loss of the supply

train was devastating. Charles was running out of time.

That's when an opportunity presented itself.

The Crimean Khan

situated just a couple hundred miles away contacted Charles about

joining the fight. The Khan had some scores to settle with Peter.

Why not set a trap?

Charles was running so

low on supplies that he accepted the risky gambit. He laid

siege to a castle in Poltava. It was his way of advertising "Here

I am. Come

and get me". The idea was to draw out the Russian army and

engage in a full-scale battle.

On the day of the

battle, the Khan would appear out of nowhere and spring the trap. One more victory like he

had at Narva might just be the knock-out punch he needed. Charles

knew a battle was nigh. His scouts told him that Peter

approached.

Just days before the

battle, Charles got the bad news. The Ottoman rulers that the

Khan served had ordered him to stand down.

Charles would have to

fight this one on his own. As chance would have it, Charles

was in great pain. He had recently taken a rifle shot to his

foot. With the effective scorched earth policy, the loss of

the supply train, the loss of this key ally and his own injury,

Charles surely must have thought his luck was running out.

Charles surely concluded he should have taken out Peter when he had

the chance.

|

|

Poltava

In July 1709, Charles got the fight he

had asked for, but his gamble of calling out Peter failed miserably. Poltava is sometimes known as the

"Swedish Waterloo".

Charles quickly realized

it had been foolish to

advertise his position. The whole idea was to lay a trap. But

when his Crimean Tatar ally decided not to participate at the last

minute, Charles was the one who was trapped.

Charles was appalled to

discover he was confronted by a much larger and vastly improved

Russian army who were determined to defend their homeland.

The Swedes who stood

against the Russian army at Poltava in central Ukraine were

outnumbered and

outgunned. They had taken the field with excitement, but soon

realized this was a much different Russian army they were facing.

|

This time

the Russians were far better equipped than at Narva. The

Swedes were swiftly battered into submission by the powerful Russian

artillery. Peter had used his home field advantage to bring

every big gun he could find to use against the enemy.

Peter had also used the time to round up an enormous army.

Peter, acting as commander, used 53,000 troops to handily defeat the

Swedish army that had dwindled to 19,000 troops. Charles was

spirited off the field and took off fleeing for

Turkey in fear for his life. With bullets whizzing past him,

Charles just barely escaped across a

river by the skin of his

neck. Now the humiliation was his. The shoe was on the

other foot... probably the foot that wasn't shot.

The Battle of Poltava in 1709 represents one of the key victories in Russian

military history. Interestingly, the military plan of operations at

Poltava was of Peter’s own design. Peter had just gained his first

significant victory against a tested opponent.

Military historians view

the swift defeat as a major turning point in the fortunes of the two

countries involved. In analyzing the seeds of the Swedish

defeat, they concluded the Swedish troops

were overextended. Their years of chasing their opponents across Europe

had worn them down. Their food supply problems had weakened

them and their low supply of

gunpowder caused serious problems on the battlefield. But the

biggest mistake of all was simply staying in one place too long so

that Peter could take careful aim.

The

Dawn of the Russian Empire

|

There was a great irony

in Peter's victory at Poltava. In Round One, Charles had used

Peter's siege at Narva as an opportunity to pin him down.

How ironic was it that

in Round Two Charles had played right into Peter's hands with his

own siege strategy. Now that the tables were turned, the

Swedish had turned into sitting ducks against the vast Russian

artillery.

However, there was one

difference in the outcome. Peter showed absolutely no mercy.

No surprise there.

Peter reaped quick

rewards from Poltava. For the next several years, Peter took

advantage of several opportunities to snap up more Swedish

territory. With Charles stuck in Turkey along with the remnants of

the Swedish army, he was unable to come to the defense of Sweden's

Baltic properties. Peter was able to stage

successful assaults on Sweden's valuable eastern Baltic ports, including Viborg, Riga, and Tallinn (Reval) in 1710.

Peter even got Narva

back! Peter suddenly had more Baltic Sea ports than he

knew what to do with.

The newly-powerful

Russian army was able to advance on Livonia, Ingria and Karelia as

well. Sweden would never get these territories back.

From this point on, this once great nation would see its borders

shrink dramatically.

The Battle of Poltava in 1709 spelled the end of the Swedish Empire and

marked the

rise of the Russian Empire.

Oddly enough, Poltava

did not mark the end of the hostilities. Despite the Russian

success, Charles stubbornly continued the war against the advice of

his generals. Then one day in 1721 Charles got shot in the

head during a battle.

With its leader dead,

Sweden immediately sued for peace. In 1721 Sweden ceded the eastern shores of the Baltic to Russia (the striped areas

were given to Russia). The Great

Northern War had finally ended. Peter's victory in the Great

Northern War radically altered the balance of power in northern and

eastern Europe.

|

Winners and

Losers

|

The defeat of Sweden and the loss

of most of its overseas territories other than Finland and

Stralsund

rendered Sweden a minor power once again.

The events of the war

revealed for the first time decisively the political and military

weakness of Poland and Denmark.

Russia, by contrast, had defeated the former

great power of the region, recaptured a valuable slice of Finland

known as Karelia, acquired the Baltic provinces and part of Finland,

and founded St. Petersburg as a new city and new capital. Without

question, Russia benefitted greatly from this war.

|

|

These acquisitions gave Russia a series of seaports to support both

trade and a naval presence in the Baltic Sea, as well as a shorter

route to Western Europe. Russia had finally gained its long coveted

window to the west.

Victory in the war

justified Peter's aggressive program of military, administrative, and economic reforms and

the Westernization of Russian culture. It also enormously reinforced

his personal prestige and power.

In November 1721, to

celebrate the long-coveted conquest, Peter officially assumed the

title of Emperor of Russia. Peter simultaneously declared Russia

had now become the Russian Empire. This proud moment was quite

different from Peter's dark nights of the soul after Narva 20 years

earlier.

Peter would live only

four more years, but on his deathbed he surely considered himself

fortunate to have lived long enough to see that his life projects

had brought Russia so much success.

As for Sweden, the

Finnish War of 1809 between Sweden and Russia saw control of Finland

go to the Russians. This was the final nail in the coffin of

the Swedish Empire. Sweden's days as Europe's third largest

country were long gone.

And all because a

teenager blinked when given the opportunity of a lifetime.

|

|