Cancer

Diaries

Part Six:

Mysteries of Science

Written by

Rick Archer

September 2013

Forward

In our previous chapter

on Morris Fishbein, I made little

effort to disguise my shock and contempt for people like Fishbein

who have gone out of their way to suppress natural cures for cancer.

In their desperate attempt to hang onto the existing ineffective and

quite painful chemotherapy-radiation-surgery treatment commonly used

today, millions have died and millions have suffered. Their

motive appears to be greed and money, the so-called root of all evil.

In the process, I have

been accused of maligning the Medical Establishment.

I grow weary of having you repeatedly malign the motives of "the

medical establishment" and the intelligence and the commitment

to the health of their patients of physicians who do not agree

with your point of view.

If I given anyone else a

similar impression, please accept my profound apology. My

Cancer Diaries are hardly an indictment of the entire Medical

Community.

|

|

| |

|

The Origin

of My Respect for Doctors

|

|

|

Considering the anger I

have displayed towards Mainstream Medicine, it may come as a

surprise to learn that I have profound respect for doctors and

medical researchers. Yes, I think the medical industry

completely deserves the criticism implicit in these stories.

Yet at the same time, I think doctors are brilliant people.

Maybe that is why I am so disappointed in them. Why they allow

these crooks to dominate them is difficult to comprehend.

The origins of my

respect began in college. As you may know, Johns Hopkins,

my alma mater, is famous for its medical program. That

includes its prestigious Pre-med program for aspiring

physicians. I suppose you would have to be very serious about

medicine to see the beauty in disease.

It is a real advantage

to list a Hopkins degree when applying to medical school. If two

people apply for medical school with similar grades, but there is

only one spot open, a degree from Hopkins will make a big

difference.

During my undergraduate

years at Johns Hopkins, I had the privilege to count numerous

pre-med students as friends. I can testify from personal

experience that every one of them were among the most intelligent,

hard-working students on campus.

|

I can also relate from

personal experience that I was able to observe first-hand the

rigorous gauntlet these young men faced in their search for a career

in medicine.

It is common knowledge

that medical schools take only the best and the brightest.

Since there

are only a limited number of spots available in medical school, with

so many equally talented people vying for one of those precious spots, the

competition for grades at Hopkins was brutal. As always when

the talent is equal, it usually boiled down to who worked the

hardest.

Here again, I had personal experience.

One of my part-time jobs was supervising Hutzler's Reading

Room, a large, cozy study hall. This ultra-quiet room was

designed for study. The lighting was

subdued and the long room was carpeted to keep down the

noise. This room was full of bookcases, comfy

leather chairs and long, smooth study tables made out of

oak. Hutzler's was open all night long. In my

opinion, Hutzlers was more popular for studying than the

Library.

My job gave me the perfect vantage point to observe the

uncanny discipline of the pre-med students. I watched

in quiet respect as they toiled away endlessly in their

attempt to master the material. I had a pet theory all

the Pre-meds congregated in there because misery loves

company.

On the nights before

one of the big exams, the Pre-meds were always the last to

leave. For that matter, some didn't even bother to

leave. They were going to pull what was known as an

"all-nighter". Maybe this would give them the edge to answer that one make-or-break question on the next day's chemistry test.

That question might become the difference between making the A instead of the B on

the All Mighty Curve.

|

|

Sometimes I

pulled

the graveyard shift.

All night means

ALL NIGHT. The room never closed. Someone had to

supervise. I hated this midnight till 7 am assignment

because I was useless the next day, but someone had to do

it. Fortunately our group was large enough that I only

drew the assignment every two weeks or so. My fellow

workers and I

rotated this unwanted time slot depending on our own

homework and test schedules.

Once in a while,

I would get the graveyard shift on a night when there was a

huge Chemistry test the next day. My elevated chair at

the front desk gave me an eagle's nest to survey

the room. Slowly but

surely the room would thin out until the only ones left were

the Pre-meds. On test night, at 2 am there might be

fifty or more boys scattered across the vast room.

Considering the class size was 200, that meant 1 in 4

students were studying deep into the night. That's

Hopkins for you - 25% of the entire Chem class pulled an

all-nighter. When I say these boys were "serious", I

am not exaggerating.

|

When they had to rest, they would doze in a

chair or simply lie their heads down on the table. Then

they would wake up and study some more, leaving only when it

came time for the test. That is the kind of sacrifice they

were willing to make to get into medical school. These

young men were dedicated.

You may have

noticed I said 'young men'. The school didn't go coed

till my Senior year. That was they year they let in 9

young ladies.

Considering there were 2,000 male undergraduates, why even

bother? When faced with 1 in 200 odds, this same view

was shared by my entire circle of pre-med friends.

Trust me, I was lonelier than hell throughout college. The

only reason I went to Hopkins was they

gave me a full scholarship. I was very poor. But

most of my Pre-med friends had a wide choice of schools with

actual women. Even though these boys knew full well how lonely they would be for female attention

for four long years, they still chose to come to Hopkins.

That

alone should indicate how much a "Hopkins degree" meant to these

Pre-med students.

|

It is to medical

people

like those After-Midnight Warriors that I extend my apology.

I understand that my Cancer Diaries have given their amazing profession

a black eye. However, now that I have shared the story

of Morris Fishbein, at least

now it should be obvious why I am so angry. Although

Fishbein is gone, I have no doubt that he groomed

someone as equally ruthless to take his place. Judging

from the Burzynski story

in Chapter Three, obviously the baton has been passed on. When I speak of the "Medical Establishment",

that is simply because I have no better name to use for the

amoral cut-throats at the top. Maybe I will call them

the Conspirators from here on out.

For those

medical professionals who resent my use of the term "Medical

Establishment", I hope this clarification helps. I

might add that this does not in any way mean I excuse the

Conspirators responsible for the witch hunts against the alternative

cancer cure practitioners. There is no

doubt in my mind these corrupt individuals exist. If

their presence gives the Medical profession a bad name, then

I have a suggestion. Get rid of them.

That said,

despite the evil at the top, there can be no question that

American medical schools produce some of the finest medical

minds in the world. Perhaps the greatest moment in

American medical history took place in the Fifties.

|

|

The

Scourge That Crossed Our Nation

Earlier I spoke of

my acute loneliness during my college

years at Johns

Hopkins. There were times when I

just couldn't take it anymore. About once a month, I would drive

from Baltimore, Maryland, down to

Northern Virginia for a much-needed break.

My beloved Aunt Lynn and Uncle Dick

knew how much I was struggling. They gave me

permission to come down any time I was desperate for human

warmth.

During the day, Lynn would invariably

sit me down for a pep talk. She would ask how it was

going. Mostly she would offer sympathy and perhaps a

suggestion here and there.

Just knowing this kind woman cared about me made all the

difference in the world.

To this

day, I care for Lynn as if she were my own mother.

|

Uncle Dick was my mother’s

favorite brother.

I was named for him. However,

thanks to Dick Nixon, I preferred to shorten my name to

'Rick'.

Uncle Dick was a very kind man. Over the years, my

uncle became a real hero to me. There was a time when

Uncle Dick actually paid my way to an expensive private

school here in Houston out of his own pocket.

In fact, he did it for two years!

That incredible gesture paid huge dividends. It led to

my full scholarship at that private school which

in turn led to my full

scholarship to college which in turn

led to my full scholarship to

graduate school. Without Uncle Dick’s

generous sacrifice, this

chain of scholarships would never

have been possible.

Small wonder that my Uncle Dick

is a man I admire. I owe much to

Dick and Lynn, two people who were better parents to me than

my own set.

Like Aunt Lynn, Uncle Dick was equally

concerned about me. We would have our conversations

late at night after Lynn and his four children had gone to

bed. We would watch Johnny Carson together till the

wee hours of the morning. This was a special time for

me.

One night

I asked him why he

always limped so badly. Uncle Dick smiled wanly.

“You

wouldn't know this,

Rick, but I was once a very good athlete. Back in high

school, I was captain of my football team. I could

not only walk just fine, I could run

all day. I was a lineman

and pretty good at it. I even tried out for the

Penn State football team, but learned quickly I simply

wasn't big enough to play major college football.

My first clue came when I lined up across Rosie Grier, a

huge man who would go on to be All-Pro for the Rams.

He flattened me like I was a bug.

However I loved the game, so I stuck around. I was accepted onto the Gold team that

scrimmaged with the varsity every day.

I

was still in the Navy when I

contracted polio. It was 1955

and I was stationed in

Maryland near the Chesapeake Bay.

I think I contracted it from

the water at the Patuxent River Naval Station.

One day out of nowhere I noticed I had

a fever. I was staggering and

losing my balance. The next thing I knew, I collapsed.

I could not even walk.

My buddies had to half-carry me to

the clinic. The doctors suspected polio almost

immediately. Then I called Lynn to give her the

bad news. I was scared. Everyone was terrified of

polio. I honestly wondered if I would ever walk

again.

It took

Lynn

about half a day to drive down from Pennsylvania.

When I saw her, Lynn was white as a ghost. The poor woman was paralyzed with fear.

Sure enough, her worst fears were confirmed.

The doctors were now certain I had

polio.

Poor Lynn was in shock.

She knew there was no cure for polio. At first she was

worried that I would be stuck in an iron lung for the

rest of my life. Then she was worried that I would

never walk again. Fortunately

while I was in the hospital my condition did not get

worse.

I was in a lot of pain for a year, but in time

the pain subsided. However, I

still could barely walk. I

could only get around with the

use of crutches. It

would be years before I could walk again without a

crutch.

This was a

pretty bleak time for us. We had an infant son and

I was a cripple. Thank goodness IBM took a chance

on me. Why I will never know. I couldn't

even walk into the room for the interview. I could

not help but notice the interviewer's eyes switched to

my crutches on several occasions.

That

was twenty years ago. My weak leg is

still a real

handicap. Every time I

climb steps I want to scream

in pain. Some

days are better than others

for me, and some days not so

much. Eventually you learn

to live with the suffering.”

The Emergence of Polio

Polio

has been around for a

long time. It has existed quietly

for thousands of years as an endemic pathogen. Polio

emerged in a big way in the 1880s when major epidemics began

to occur in Europe. Like most viruses, it began to

spread. Soon after, widespread epidemics appeared in

the United States.

The first major polio

epidemic in the United States hit Vermont in 1894 with 132

cases. A larger outbreak struck New York City in 1916, with

more than 27,000 cases and 6,000 deaths. As the number of

polio cases grew, the paralytic disease changed the way

Americans looked at public health and disability.

Epidemics became regular

events, primarily in big cities during the summer months.

These polio epidemics left thousands of children and adults

paralyzed. It also killed many of its victims.

No one was even sure where the disease came from. The

fear of catching it became rampant; this provided the

impetus for a "Great Race" towards the development of a

vaccine.

The fight against polio got

under way in 1938. That is when Basil O'Connor founded

the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis thanks to

the request of our nation’s most famous polio victim.

|

And

who might that be?

His name was Franklin Delano

Roosevelt, America’s president.

Basil

O’Connor was a former law partner of President.

One day Roosevelt called O’Connor into his office and asked him if

he would head up this important project. O’Connor

agreed on the spot.

Many people think that

Roosevelt tried to keep his polio a secret. That is

not true. The American public was aware that Roosevelt

had been stricken back in the 1921. What they weren’t

aware of was how serious the problem was.

Indeed, when the world wasn’t looking, Franklin Roosevelt was

an invalid confined to a wheelchair.

Like my uncle who

wondered what message his crutches sent to the interviewer, Roosevelt

was certain the image of that wheelchair

would ruin his chances of election. Roosevelt made sure that no one outside his immediate circle knew that

he was totally crippled.

Roosevelt was 39 years old

when he had been stricken in 1921. However Roosevelt

refused to give up his political ambitions.

And why should he?

Roosevelt might be handicapped, but his mind wasn’t

affected. After a lengthy convalescence, he decided to

run for the governor’s office in New York. However

Roosevelt greatly feared the American public would turn

against him if they knew how badly he was crippled. He

needed their respect, not their pity.

|

So the future governor of

New York and 4-time American President

devised a way to keep his secret

hidden from the world. In private,

FDR spent most of

his time in a wheelchair, but in public, he had his sons

and bodyguards act as secret crutches to give the admiring

crowds the illusion of walking. The

men would walk next to the President and secretly support

him while FDR appeared to be walking under his own power. The deception

worked like a charm. The American Public was

completely fooled. If anything, they admired

FDR even more

for licking the disease which crippled ordinary people.

Personally, I imagine most

people would have admired him just as

much if they knew the

truth. I certainly admired my uncle

for his courage. But that was a chance Roosevelt wasn’t willing

to take.

|

March of Dimes

In 1938,

FDR's friend Basil O’Connor helped set

up the first March of Dimes fundraising program. Radio

networks across the land offered free 30-second slots for

promotion. Listeners were asked to send in a dime. The

response was phenomenal. The White House received

2,680,000 letters within days.

Unfortunately, World War II

intervened. It was a real shame,

but the fight against polio had to be put on the

back burner.

However, after the war,

polio returned to the forefront as Public Enemy Number One.

Polio was an especially

cruel disease because it attacked mostly children.

Parents were panic-stricken because no one could figure out

how the disease was being transmitted. Apart from the

atom bomb, America's greatest fear was now polio.

Actually, most people feared Polio

more since the chances of catching it seemed so high.

Polio

was being referred to as the worst plague in American

history. As a result, scientists were in a frantic

race to find a way to prevent or cure the disease.

|

During the war, Jonas Salk

had worked at the University of Michigan developing an influenza

vaccine at the behest of the U.S. Army. After the war

concluded, in 1947, he was appointed director of the Virus

Research Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh School

of Medicine.

It was in Pittsburgh that

Salk began to put together the techniques that would lead to

his polio vaccine. He was already well aware of the

principle of vaccination. He knew that if the body is

artificially exposed to a harmless form of a disease virus,

the body will produce antibodies that resist or kill the

dangerous form of the virus if later exposed.

Salk was

certainly not the only man who visualized a vaccine as the

solution to the problem. Where Salk differed was his

belief that protective immunity could be induced without

infection by a living virus such as those used in the

vaccines against smallpox and rabies. In developing the

influenza vaccine during the war, he had observed that protection could be

established using noninfectious, inactivated viruses.

In other words, Salk “killed” the virus first, then found a

way to use it anyway.

This was an

important observation. Early attempts to develop a

vaccine ran into numerous hurdles. A vaccine tested on

10,000 children by two researchers at New York University

provided no immunity. Then came the bad news. Because

the researchers were experimenting with highly dangerous

live vaccines, six of the participating children had been

killed. Three others were left permanently crippled.

|

|

After that

horror story, no researcher wanted to go anywhere near other

vaccine trials and no parents dared offer their children up

as guinea pigs. Progress against the disease came to

an alarming halt.

Meanwhile

Salk's research caught the

attention of Basil O'Connor, president of the National

Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. O’Connor was

impressed by Salk’s confident claim that he could create a

SAFE vaccine. On a hunch, O'Connor

decided to bet the farm on this Salk guy.

In 1948, O’Connor convinced

his organization to make Jonas Salk the point man in the

country's efforts to cure polio. They poured huge amounts of

funds into his clinic. Salk assembled a skilled

research team and devoted himself practically non-stop to

this work for the next seven years. He attacked his

project with the zeal of a missionary.

Unfortunately, the cure did

not come overnight. In fact, the problem got even

worse. There was an especially cruel epidemic in 1952.

During the worst

part of the outbreak, hospitals across the nation were filled

with crippled patients housed in iron lungs. The

victims of polio were usually children or very young adults.

Every day the newspapers published heart-rending pictures of

dozens of small children lying helpless as they were kept

alive by these giant metal breathing machines.

The cases dramatically

increased during the summer when children were home from

school. No one could figure out why.

What

could be causing this disease?

The unknown origin of the disease caused great fear. It led

parents to take extraordinary precautions.

Parents kept children home from school, avoided parks and

swimming pools, and allowed their kids to play only in small

groups with the closest of friends.

Furthermore, those friends

had to demonstrate their total health before anyone let them

in the door.

|

|

As the fear of polio

increased year after year, funds to combat it increased from

$1.8 million in the first year to $67 million by 1955.

Research continued non-stop during those years, but it looked

hopeless. To the dismay of many, everything scientists

believed about polio at first was wrong. Years had

been wasted chasing down many blind alleys. Even

worse, after the test which killed the six children, no one

had the courage to try again.

American historian

William O'Neill wrote:

“This was the situation when

young Jonas Salk entered the picture. No researcher

wanted to become a baby killer. Experiments were put

on hold. Salk succeeded where others had failed

because he decided to use a safer method known as the

‘killed virus’.”

No one really gave Salk’s

idea much hope. How can a virus

that has been 'killed' create

immunization? Despite the general lack of enthusiasm

for this approach, Basil O'Connor backed Salk totally.

After successful tests on

laboratory animals, Salk’s vaccine next had to be tested on

human beings. Now everyone held their breath. On July

2, 1952, assisted by the staff at the D.T. Watson Home for

Crippled Children, Jonas Salk injected 43 children with his

killed virus vaccine.

A few weeks after the Watson tests, Salk injected children

at the Polk State School for the retarded and feeble-minded.

To the relief of everyone, no one died and no one became

paralyzed.

In November 1953, at a

conference in New York's Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, Salk said,

"I will be personally responsible for the safety of the

vaccine."

Salk then announced that his

wife and three sons had been among the first volunteers to

be inoculated with his vaccine. That brave move won

Salk a lot of support. If he was willing to risk his

own family, then maybe he could be trusted. Salk

concluded his talk by saying the time had come to take his

vaccine to the national level. Salk had inspired the

entire country.

Throughout 1954, the scale

of the support for Jonas Salk’s project was both staggering

and exhilarating. It reminded many people of the same

energy that fueled America’s entry into World War II.

Thanks to the hope generated

by Salk’s potential cure, the entire country was galvanized.

In 1954, at least one hundred million people contributed to

the March of Dimes. Seven million donated their time

and labor to put on the March of Dimes. They included

fund-raisers, committee workers, and volunteers at clinics

and record centers.

Now that the money was

there, Salk devised a massive test program. The field

trial set up to test the vaccine developed by Salk and his

research team was the most elaborate program of its kind in

history. It involved 20,000 physicians and public

health officers, 64,000 school personnel, and 220,000

volunteers.

Over 1,800,000 school

children ages six to nine participated in the trial.

Joining America in the test were

children from Canada and Finland.

Known

as “the Polio Pioneers”, half the children received the

vaccine and half received a placebo. Furthermore one-third

of the children who lived in areas where vaccine was not

made available were observed to evaluate the background

level of polio in this age group.

The entire country went “all

in”. Everyone had a stake in the outcome.

Everyone did whatever they could to help.

A 1954 Gallup poll showed

that more Americans knew about the polio field trials than

could give the full name of the US President. According to medical author

Paul Offit,

"more Americans had participated in the funding,

development, and testing of the polio vaccine than had

participated in the nomination and election of the

president."

|

|

On April 12, 1955, the

results of the massive nation-wide test

were ready to be announced. This date had been

selected for a reason. It was exactly 10 years to the

day since the death of President Roosevelt, the man who got

this project started in the first place.

During the test phase, Salk

had asked his mentor Dr. Thomas Francis to be the monitor of

the results. So it was Dr. Francis who took the podium

at the University of Michigan that day.

Five hundred people filled

the room. That total included 150 press, radio, and

television reporters. There were 16 television and

newsreel cameras standing on a long platform at the back.

Across the country, 54,000 physicians were sitting in movie

theaters to watch the broadcast on closed-circuit

television.

The event was also being

broadcast live on radio. Eli Lilly and Company had

paid $250,000 – a monster sum in those days - to broadcast

the event. It was money well spent. Every single

American turned on their radios to hear the details,

department stores set up loudspeakers, and judges suspended

trials so that everyone in the courtroom could hear.

Europeans listened in on the Voice of America. The

entire planet held its breath.

As Francis took the podium,

the room fell to a dead silence. The anticipation and

the tension was practically unbearable. Francis stood

silent for a moment, obviously taking in the amazing drama.

Then Francis smiled.

He declared that the vaccine was not only safe, it was

effective. The room erupted with joy. Everyone

began hugging the nearest person and cried wrenching tears

of happiness.

|

|

|

Paul Offit writes about the

event:

"The

presentation was numbing, but the results were clear: the

vaccine worked. Inside the auditorium Americans tearfully

and joyfully embraced the results. By the time Thomas

Francis stepped down from the podium, a national celebration

had broken out.

Church bells were ringing across the

country, factories were observing moments of silence,

synagogues and churches were holding prayer meetings, and

parents and teachers were weeping.

One

shopkeeper painted a sign on his window: ‘Thank you, Dr.

Salk’.

'It

was as if a war had ended and the most

bitter enemy defeated,' one observer recalled."

Rick

Archer's Note: As one can see, the results were astounding. In the two years before the

vaccine was widely available, the average number of polio

cases in the U.S. was more than 45,000.

By 1962, that number had

dropped to 910, mostly from children in rural areas that had

no access to vaccination.

n the days that followed, the next step was to immunize the

entire nation. I was one of the millions of kids who

participated. I guess I was about

6 at the time. A sad irony

is that the Salk vaccine was released to the public about

one month after my Uncle

contracted polio.

|

As for Jonas Salk,

he was hailed as a

"miracle worker".

There is one final footnote

to this story.

Jonas Salk had no interest

in personal profit. Salk’s sole focus had been to develop a

safe and effective vaccine as rapidly as possible. His only

wish was to be given the wisdom necessary for the chance to

save America’s children.

When Salk was asked by CBS

newsman Edward R. Murrow who owned the patent to his

vaccine, the scientist replied: "There is no patent.

How could

you patent the sun?"

Jonas

Salk, an American hero.

|

|

|

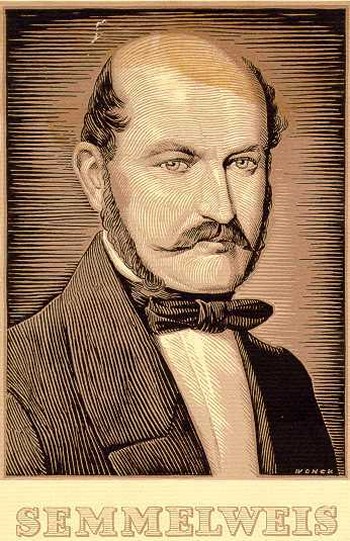

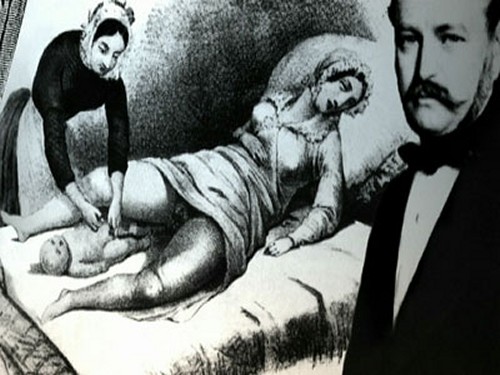

Ignaz Semmelweiss

Although

few of us have never heard of Dr. Ignaz Semmelweiss, he

is someone we all owe a great debt to. This is the

man who discovered the importance of washing our hands.

As his reward, he was driven insane.

It is a very

interesting story, so I will share it with you.

But first I would like to share an insight. My

background is in the Social Sciences which means, unfortunately,

that I have little knowledge of medicine.

So when I realized this story dealt with a medical

problem known as Puerperal Fever, my first

instinct was to look it up.

I ran across

a

medical treatise that was 35 pages long and

contained 17,000 words.

|

|

The purpose of the paper was

to trace some of the ideas on puerperal fever which were

published in medical treatises during the period from

1760 to 1850.

After

reading the article for a while, I realize I was

absolutely stunned by its complexity.

It staggers the mind just how much information is out

there. There was no way I could absorb this much

material unless I really put my mind to it. I

decided it wasn't worth my effort.

That is when it

dawned on me that today's doctors have the identical

problem. They are besieged by so much information

that unless it affects them directly, the simplest

coping mechanism is to simply ignore it.

As for me, finally I

gave up. Instead I used the "Find" function to

see if there was anything about Semmelweiss relevant to

my story. I found this one single mention on Page

21:

Towards the end of the period under consideration, a

physician in Hungary produced work that was later to

be regarded as seminal in the understanding of what

is now seen as the infectious nature of puerperal

fever. However at the time, his work was largely

ignored. In 1860 Ignaz Semmelweis published work,

which he had first embarked on about fifteen years

earlier, titled "The etiology, concept and

prophylaxis of childbed fever".

Semmelweiss has not been given prominence in this

present paper, partly because his writing does not

appear to have been given great attention by his own

contemporaries.

Mind you,

this is the man who solved a problem that killed

countless women in his time, but he

rated no more than a mere paragraph in a 35 page masterpiece.

And now, with that less than stirring endorsement of our

main character, let us begin the story of a

much-maligned hero who was driven to insanity.

|

|

Puerperal

Fever in the 1800s

As it turns out, the reason none of us have

ever heard of "puerperal fever" is that it doesn't really

exist any more. Puerperal fever is now rare in the West due to

improved hygiene during delivery. The few infections that do

occur are usually treatable with antibiotics.

However, from the 1600s through the mid to

late 1800s, this disease was the leading

cause of death in child birth. Pregnant

women were terrified of getting "The Fever"

as it was called on the streets of Europe.

It is impossible to discuss health in the

1800s without discussing disease.

Consistent good health was the possession of

only a small percentage of a population.

Lacking a germ theory of disease, people ate

contaminated food, drank contaminated water,

and lived amid animal and human waste

without blinking. Life expectancy in this

era was somewhere between thirty and forty

years.

Lacking knowledge of good nutrition, people

suffered from chronic indigestion, fatigue,

anemia, food poisoning, and other digestive

ailments. The unchecked spread of bacteria,

viruses, and insects resulted in epidemics

of "ague" (aka malaria), cholera, diphtheria,

dysentery, polio, smallpox, and typhoid,

crippling or abbreviating many lives.

Tuberculosis, commonly known as consumption,

was the leading cause of death in the

Nineteenth century. Chronic bouts of

influenza, pneumonia, and other endemic

maladies further reduced not only life's

quantity but its quality. Life was

very grim in those days, especially for

children and mothers. Not only did

half of all children die before their tenth

birthdays, countless women died in

childbirth.

|

|

Semmelweiss

Dr.

Ignaz Semmelweis was the

chief resident in the First Obstetrical Clinic of the Vienna General

Hospital back in 1846.

His unit saw mostly poor women, many

of whom were prostitutes. Back

in those days, pregnancy was seen by many

women as

a death sentence. It was considered

far safer to end the pregnancy.

To combat this problem, maternity

institutions such as the one in Vienna were

set up across Europe to address the rising

problem of infanticide of illegitimate

children. The clinics

charged no fee and offered to care for the infants.

This made the clinic attractive to underprivileged women. In return

for the free services, the women would be subjects for the training

of doctors and midwives.

|

|

Semmelweiss had no

particular interest in Puerperal fever, but he

knew exactly what it was. Puerperal fever was a devastating

disease back in his day. It affected women within the first three

days after childbirth and progressed rapidly, causing acute symptoms

of severe abdominal pain, fever and debility.

Semmelweiss oversaw two

units. In his role as supervisor, Semmelweiss was presented

with a strange problem

right out of the Medical Mystery chapter. The First Clinic of

the hospital had an average maternal mortality

rate due to puerperal fever around 10%. The death rate of

the Second

Clinic was considerably lower, averaging less than 4%.

Unfortunately this

strange disparity

become

known on the streets outside the hospital. The two clinics

admitted on alternate days but due to the bad reputation of the

First Clinic, women begged to be admitted to the Second Clinic.

If they were assigned to the "Death Clinic", some women

were so afraid of dying that they would rather

give birth in the streets. They would have

the baby delivered at home, but would

pretend to have given sudden birth en route to the hospital,

a

practice known as street births. This

meant they would still qualify for the child care benefits without

having to be admitted to the clinic.

|

Semmelweiss was

puzzled

about several things. First, he could not begin to imagine why the

incidence of puerperal fever was so much

higher in one unit than the other.

Second, the problem

was actually worse than just 4% compared to 10%. On certain days,

the "Death Clinic" would mysteriously be visited by a rash of deaths

while on most days there was no difference between Clinic One and

Clinic Two. To Semmelweiss, it was like playing Russian

Roulette. Five out of six days there was no danger at all, but

on the bad days, watch out. Even more troubling, the rate had

risen to 18%.

Another thing

Semmelweiss was puzzled about was

the fact that puerperal fever was rare among women giving

street births.

"To me, it

appeared logical that patients who experienced street births

would become ill at least as frequently as those who delivered

in the clinic. What protected those who delivered outside the

clinic from these destructive unknown endemic influences?"

|

|

Semmelweiss was a sensitive and deeply humanitarian

man.

He was severely

troubled by the higher mortality rate in his First Clinic and took

it personally. In his

words, "these deaths made me so miserable that life seemed worthless."

With his conscience tormenting him day and night, the search for the cause and control of this pitiless disease became

his life's work.

Semmelweiss started a

meticulous process of eliminating all possible differences.

Since the two clinics

used almost the same techniques, the doctor noted the individuals

who worked there were the only major difference.

The First Clinic, aka the

Death Clinic, was the teaching service for medical students. The Second Clinic had been selected in 1841 for the instruction of

midwives only. Try as he could, Semmelweiss could not see how

the more skilled physicians might be contributing to a higher rate

than midwives. If anything, it should be the other way around.

The trained physicians should surely have the safer clinic.

Semmelweiss reviewed the

facts.

- Street births were safer than midwives.

- Midwives were safer than physicians.

Semmelweiss grew more

puzzled by the minute. This made no sense.

A year passed without

Semmelweiss making the slightest bit of headway. He was

growing increasingly frustrated.

Breakthrough

The breakthrough

occurred in 1847 following the tragic death of his good friend Dr. Jakob

Kolletschka.

Recently Kolletschka had been accidentally poked with a

student's scalpel while performing a postmortem examination.

Now it was time for the

medical examiners to see why Kollestschka had died. Kolletschka's own autopsy showed a pathology identical to that of

the women who were dying from puerperal fever.

A series of questions raced through the

doctor's mind. Semmelweiss speculated

that the scalpel that had first cut through

a cadaver had likely caused his friend's

death.

Was there something deadly inside that

cadaver? And what was on that scalpel

that could make a man sick? Although

the naked eye could see no connection, Semmelweiss

imagined there had to be some connection between cadaveric contamination

and puerperal fever. Was it possible that

doctors and medical students working with cadavers could be somehow

giving a disease to the women during delivery?

Noting that students

move between the dissection room and the delivery room without

washing their hands, on a hunch, he set a new policy. From now on,

doctors must wash their hands in a chlorine solution when they left

the cadavers. Maybe the problem was caused by dirty hands.

Semmelweiss had

concluded that he and the medical students carried some sort of

mysterious "cadaverous particles" on their hands from the autopsy

room to the patients they examined in the First Obstetrical Clinic.

This theory would explain why the student midwives in the Second

Clinic, who were not engaged in autopsies and had no contact with

corpses, saw a much lower mortality rate.

One problem - the suggestion of some

sort of unknown "cadaverous material" was a real stretch. The

germ theory of disease had not yet been developed. Semmelweiss

was taking a real chance by suggesting the existence of some danger

that no one could see.

|

|

|

|

On the other hand, it

seemed worth the risk to at least test his theory. He

instituted a policy of using a solution of chlorinated lime, a type

of bleach, for washing hands between autopsy work and the

examination of patients.

Semmelweiss found that

this chlorinated solution worked best to remove the putrid smell of

infected autopsy tissue. He hoped that perhaps destroying the

smell would also kill the contaminating "cadaveric" agent

hypothetically being transmitted by this invisible material.

The results were shocking. The mortality rate in the First

Clinic instantly dropped 90%. It was now comparable to that in the

Second Clinic. The mortality rate in April 1847 was 18.3%.

After two months, the rate was below 2%.

Seeing the instant

results of cleanliness, Semmelweis did not stop with washing hands.

Remembering the deadly scalpel that killed his friend, now he began washing medical instruments as well as hands.

One year later, the death rate in his clinic was down to zero.

It wasn't a miracle... it was the triumph of medical intuition

combined with observation and common sense.

|

The Downfall of Semmelweiss

Imagine curing one of

the most dreaded diseases of the time and being hounded to death for

your trouble. It seems inconceivable, doesn't it?

Women were terrified of this disease. Once a woman contracted

it, the fever was a death sentence. Should not Semmelweiss

have become a hero just like Jonas Salk?

Dr. Ignaz Semmelweiss had essentially eradicated child bed fever

during childbirth simply by advocating for increased hygiene in the

delivery room. One would assume that Semmelweiss would become

a celebrated man. Such was not the case. His life was

now ruined. How can this be?

At first, Semmelweis

said nothing. It was one thing to simply order compliant

medical students to wash their hands. They were used to doing

what they were told and not ask questions.

It was an

entirely different matter to expect a group of eminent,

dignified physicians to suddenly accept some crazy theory of

'cadaverous particles'. Semmelweiss expected that his theories would be met with

skepticism.

At the time, there was quite a lot about disease

that was not understood. There were all sorts of theories

attributing disease to many different and unrelated causes.

With no knowledge of germs, doctors of that day did not

believe hand washing was needed.

"Doctors are gentlemen, and

gentlemen's hands are clean."

Semmelweiss didn't

agree. His hypothesis

was there something on those hands that transferred to the women.

However, he knew his idea that cleanliness was the answer would be considered extreme. He thought it safer to keep his mouth shut.

However, a friend

published two papers on the method. Semmelweiss could hide no

more and now he was ordered to explain himself. The doctors laughed

and jeered. Semmelweiss was largely ignored, rejected or

ridiculed.

|

|

The hospital director

had reacted fiercely. Semmelweiss had made a dangerous enemy.

The director felt

his leadership had been criticized. He retaliated by blocking Semmelweiss' promotion. Acting on the director's cue, the

Viennese doctors turned on the Hungarian immigrant.

He was now a stranger in a strange land. Semmelweiss was completely isolated

by a sea of hostility.

After

a year of harassment by the medical community in Vienna, Semmelweiss

was dismissed from the hospital for political reasons. He was

forced to move back to Budapest.

There he brought his

methods to a far more primitive hospital. Semmelweiss went to work.

He cut the death rate by puerperal

fever to less than one percent, but didn't stop there. By

performing autopsies on all victims, he systematically isolated the

various causes of death. He set up control groups and kept careful

statistics on his methods. Finally, in 1861, he wrote a book

on his methods.

The book went nowhere.

Despite overwhelming

theoretical arguments and empirical evidence, Semmelweiss' ideas

were not embraced. Instead, he was treated with scorn and attacked

by his fellow physicians. To the doctors of the mid-19th

Century, the very idea that a gentleman could cause illness because

he was unclean was offensive.

Understandably,

Semmelweiss grew more and more frustrated. How stupid

could these people possibly be? Semmelweiss could not

accept the obstinacy of people who were supposedly dedicated to

healing. He was outraged by the indifference of the medical

profession. Semmelweiss decided to retaliate. He began writing open and increasingly angry

letters to prominent European obstetricians. He grew more and

more polemical, at times denouncing his peers as 'irresponsible

murderers'.

|

|

Here is a fascinating

example.

Rebuffs to

his struggle for wider application of his doctrine were

disturbing to Semmelweis. He particularly resented attacks by

the self-serving forces of the authoritarian medical

establishment, and he lashed out against them. His doctrine was

opposed by powerful members of the academic hierarchy such as

Professor Kiwisch and Scanzoni of Würzburg. Mortality from

puerperal fever on the services of some of these Professors of

Midwifery ranged as high as a barbarous 26% under Kiwisch at

Würzburg.

The

damning evidence that they were themselves the remorseless

messengers of death was a scarcely veiled threat to their pride

and eminence. Semmelweis was unsparing in his condemnation of

those who denied his doctrine in spite of the high mortality

rates in their own institutions.

This

excerpt come from his open letter to Professor Scanzoni of

Würzburg who, while professor at Vienna, had disparaged

Semmelweis's earliest work:

Your

teaching that the Würzburg epidemic of childbed fever is

caused by unknown atmospheric influences or puerperal miasma

is false. It is based on the dead bodies of lying-in women

slaughtered through ignorance. . . I have formed the

unshakable resolution to put an end to this murderous work

as far as lies in my power so to do. . . If you continue

teaching your students this false doctrine, I denounce you

before God and the world as a murderer, and the History of

Puerperal Fever will not do you an injustice when, for the

service of having been the first to oppose my life-saving

lessons, it perpetuates your name as a Medical Nero.

[

SOURCE ]

Wow... a Medical Nero!

That was quite a tirade.

The years of controversy had turned the man so bitter that he had lost

all patience.

His contemporaries,

including his wife, believed Semmelweiss was losing his mind.

Sadly, they were probably right. The four years since the

publication of his book had turned him into a ranting madman.

In 1865 he was committed to an asylum.

Strangely enough,

fourteen days later he was dead. Although some say Semmelweiss

was beaten to death by the guards, the consensus is that Semmelweiss

either cut his finger or perhaps was wounded during the beatings.

If true, in the dirty asylum, Semmelweiss had fallen victim to the

greatest of ironies.

He had contracted

the same infection that had become his life's work. He had

saved the lives of thousands of mothers only to die from the same

disease that had killed his friend Kolletschka.

Whatever the truth, Semmelweiss

died a broken, pitiful man.

Fortunately, Semmelweiss

did not die in vain. That same year, Joseph Lister began

spraying a carbolic acid solution during surgery to kill germs.

Lister was a friend and protégé of the brilliant French scientist

Louis Pasteur. Once Lister ran across Semmelweiss' manuscripts, he

sensed

immediately that Semmelweiss was right. Lister instituted

practically every suggestion Semmelweiss had made. Soon

puerperal fever ceased being a threat.

In the end, it was

Joseph Lister who gave our unhappy hero his due. Lister said, "Without

Semmelweiss, my achievements would be nothing."

In her book Woman As Healer, Jeanne Achterberg wrote that the

colleagues of Semmelweiss "simply refused to believe that their own

hands were the vehicle for disease." Achterberg continued,

"Instead they attributed the disease to a spontaneous phenomenon arising from the

'combustible' nature of the birthing woman."

Achterberg adds that Semmelweiss was treated

as a heretic, someone little better than a witch at Salem Village.

"Semmelweiss' academic rank was lowered, his hospital

privileges restricted. Despondent, he was committed to an insane

asylum, where he died of blood poisoning, a disease not unlike the

puerperal fever he had almost conquered."

It would be difficult

for one to imagine a more cruel fate.

The progress

of science is strewn, like an ancient desert trail, with the

bleached skeletons of discarded theories which once seemed to

possess eternal life

—

Arthur

Koestler

"Evidence that might cause us to question our beliefs is

used instead to reinforce our beliefs. If long held

beliefs are challenged, we feel a need to defend them.

And as long as we are defensive, our vision will be

cloudy at best. To

remain blind to our beliefs and paradigms, to refuse to

question them, cuts off any real possibility of change."

—

Dr.

Julian Whitaker

|

|

|

| |

|

|

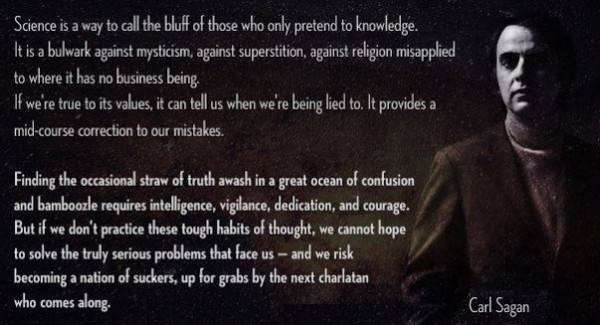

Science

Has Been

Wrong Before

|

|

I believe science and

medicine offer amazing intellectual

challenges. Yes, unlike the

doctors of the Semmelweiss era, we know all about germs now.

And we know a lot more than that. But I am certain

there are still more invisible things in medicine and

science that we don't know about yet. There is so

much mystery in the Universe. Anyone born with

a sense of curiosity is bound to

be endlessly fascinated by a scientific

or medical career probing for answers.

That includes medicine. Anyone who has ever watched the TV

medical show House knows full well that medicine

holds all kinds of unsolved mysteries to this day.

The story of Semmelweiss is a perfect

example that Science doesn't always get it right. When

confronted with glaring evidence that dirty hands were the

likely culprits in the high mortality rate of the mothers,

the doctors of 1860 behaved like closed-minded bigots.

Talk about dropping the ball!

Today it is so painfully obvious that Semmelweiss was right

that we forget the men who rejected Semmelweiss were the

most educated members of their generation.

Today we laugh. My word, that

happened practically back in the Stone Ages!! How

thick-headed can those cavemen possibly be? We are so

much smarter today.

But let's stop for a second and ask

ourselves this question: Is it possible we can be just as

blind today on certain things as these men were 250 years

ago??

I have no medical training. I

barely know the difference between a peptide and a bacteria.

Who am I to argue that there have been alternative cures for

cancer?

Take a

man like Stanislaw

Burzynski from

Chapter Three. In

my opinion, Burzynski is very close to a breakthrough in

cancer treatment. But that's just my opinion.

I am very well aware that I have no

training and I have no proof. So I decided to ask a

Hopkins-trained medical researcher what he thought about

Burzynski.

Rick's Statement:

"Let Burzynski go about his

business without the constant harassment. If the man is

wrong, then let his failed results speak for themselves.

Like herbal tea and apricot seeds, his cure isn't

'hurting' anyone, so leave him to do his research in

peace. "

Hopkins Cancer Researcher:

"Let me first start by explaining

why I am hesitant about even entering this discussion.

To discuss this with you would be like an astronomer

commenting on an article written by a layman that the

moon is made of cheese. The debate is, frankly, beneath

him/her. And it would be insulting to have his or her

name connected with such a debate.

That is how I and 99% of the

scientific and medical field feel about Burzynski's

current approach to cancer therapy.

(Just as I'm sure 99% of

astronomers feel the moon is not made of cheese, despite

how closely it resembles swiss cheese with its' color

and craters). And don't get me wrong; there are many

spirited debates in biology, in academic and industry

settings, including dozens of countries on what will

bring us closer to the cure.

But these are based on peer

reviewed, independently verified data. Data

collected by testing with preclinical models (i.e.

tissue culture cells, mice, ...), and then clinical

trials in humans, measuring safety and efficacy.

Burzynski has none of this bolstering his "cure".

And your conspiracy angle is

ludicrous considering the number of people and

governments that would have to be involved.

At the risk of being insulting,

Rick, you don't know, what you don't know."

I think that sums it up pretty well. This

comment made by a conventional cancer researcher is typical

of the attitude of Mainstream Medicine towards Burzynski.

As

it stands, the majority of today's medical community

denounce Burzynski to be little

better than a fraud.

To even begin to give Burzynski the benefit of the doubt is

beneath contempt.

|

This man seriously doubts the

possibility that Burzynski is on the right track. His

mind is made up.

Let me

say this man has a point. For me to be right

that Burzynski's cure for cancer has real

potential, countless

members of modern medicine

who know a hell of a lot more about

medicine than I do would have to be taking the wrong

approach.

For example, it seems ludicrous that

people would bet on a philosophy major like me over a man

with a doctorate in Cellular and Developmental Biology.

Is it

even possible that he could be wrong?

Although

it seems

far-fetched that a highly-trained cancer

researcher could be wrong about Burzynski, I contend it is not

out completely out of the realm of possibility.

Over the

centuries there have been some beliefs that were real

whoppers.

History is filled

with examples of

long-held beliefs that defy all credulity.

Let's

take a fun stroll down memory lane.

|

At the risk of upsetting the Creationists,

scientists agree the Earth is a bit older than the 6,000

years as suggested in the Bible.

Current estimates, based on

radioactive dating, place the age of the planet at around 4.5

BILLION years. Hmm,

those biblical scholars may have been a bit off.

Once upon a time, the Bible was

considered a scientific work. People took it for granted

the Bible was

accurate even when it didn't always make much sense.

The age of our planet

is a good example.

Back in the 17th century, a

religious scholar named Archbishop Ussher took a hard look at the

Bible. He estimated that creation

took place in 4004 BC.

Bishop Ussher’s specific chronology

dating the creation to 4004 BC became the most accepted and popular

timeline, mainly because this specific date was attached to the King

James Bible. Add in nearly 2,000 more years

since the birth of Christ to get to the 18th

century and you get about 6,000 years.

The

church made sure that number came into wide acceptance.

|

|

What is interesting is the

number of people

today who still

take the 6,000 year

Bible estimate seriously.

Our good friend Wikipedia,

an aspiring modern day Bible in its own right, has something

to say about the controversy.

Wikipedia cites a 2006

Gallup poll saying 43% of Americans believe that "God

created human beings pretty much in their present form at

one time within the last 10,000 years or so."

The Poll adds that the

percentage of believers decreases as the level of education

increases.

Don't ask me who is right. When

I stop and think about it, I don't have any training

whatsoever to contradict the Bible or the scientists.

We have reach a point in civilization where we are all

deeply dependent on science and technology, yet hardly any

of us can even begin to understand how all this stuff works.

And that includes the methods science uses to date the

Earth.

|

Unfortunately, we are all dependent on the work of others. I

don't have any way to know how old the Earth is. So who

is right and who is wrong? Good question. It all boils

down to whom you choose to believe. While I have been trained to

accept the word of Science, other people have been trained to

accept the word of their religious leaders.

Same

thing with cancer research. Most of us have been trained to

accept the word of modern medicine. Mr. Skeptical prefers the

word of alternative medicine. Mr. Research prefers the word of

conventional medicine. As for me, I read the arguments

from both sides of the aisle and see they both make good points.

I conclude from the

cancer research disagreement

that there are a lot of things about the Universe we don’t know much

about. That is what makes the search for "The

Truth" so interesting.

When it comes to mystery, Science and

Medicine are the two best Games in town. However, both

Science and Medicine

have a long history of chasing up blind alleys. Isn't it a

shame that

God doesn't ring a little bell whenever we are on

the right track?

|

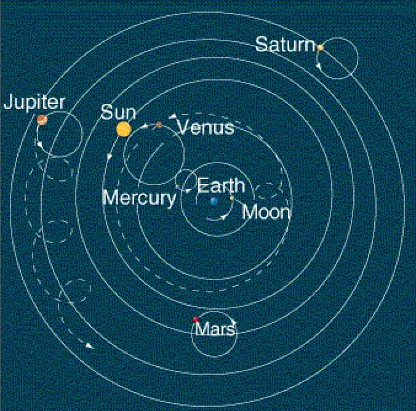

For example,

I seem to remember some guy named Copernicus who suggested the Sun,

rather than the Earth, was at the center of the galaxy. This

happened around 1543. Copernicus then had the

good sense to die immediately of old age rather than face a

firestorm of protest.

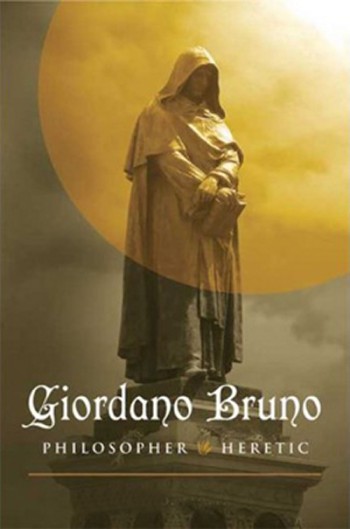

The unlucky fate of being one of the first people to agree with

Copernicus fell to Giordano

Bruno, an Italian philosopher and

scientist. Throughout his life Bruno

championed the Copernican system of astronomy which placed the sun,

not the Earth, at the center of the solar

system. He opposed the stultifying

authority of the Church and refused to recant his philosophical

beliefs throughout his eight years of imprisonment by the Venetian

and Roman Inquisitions. Finally the Church had

enough of his rebellion and sentenced him to death.

At

this, Bruno famously replied, "Perhaps you pronounce this sentence

with greater fear than I receive it."

It takes a brave man to

die for his beliefs!

On

February 16, 1600, the Roman Catholic Church executed Bruno for the

crime of heresy. He was taken from his cell in the early hours of

the morning to the Piazza dei Fiori in Rome and burnt alive at the

stake. To the

very end, Church authorities were fearful of the ideas of a

man who was known throughout Europe as a bold and brilliant thinker.

In a peculiar twist to the gruesome

affair, the executioners were ordered to tie his tongue so that he

would be unable to address those gathered.

Upon the death of

Bruno, Galileo

stepped forward to defend the Copernican

system. Bad move. Now it

fell upon Galileo to take the heat. Galileo was tried by the Holy

Inquisition

in 1633.

Galileo was found "vehemently suspect of heresy" and forced

to recant his ideas under threat of torture. Galileo,

now an elderly man too weak to resist, gave in. The

foremost scientist of his day spent the rest of his life

under house arrest.

|

|

Can you imagine the

stupidity of it all?

The man they call "the Father of modern physics" and "the Father of

modern science" was locked away for the rest of his life.

Over

the centuries religious intolerance has led to other appalling

mistakes. One need look no further than the Spanish

Inquisition or the Salem Witch Trials to know this.

Men never do

evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from

religious conviction.

– Blaise Pascal

The story of the Sun controversy is the most

dramatic, but there are

plenty of other stories where

long-held beliefs were laid to rest with great

difficulty.

Another well-known example was

the widely-held theory that the Earth was flat.

Thanks to a guy named

Columbus and a few other brave sea explorers, that notion

disappeared around the end of the 15th century. The common myth was

that the world was flat. If so, then Columbus was indeed the bravest

of the brave for risking his life by challenging that view.

Give him credit for that.

However, most scholars agree that Columbus was pretty sure the Earth

was round.

|

|

Unfortunately, modern research

now suggests that Columbus in nowhere near the

greatest explorer in history, but rather the

luckiest. There is

increasing evidence he was rewarded for being

stupid. Columbus simply made the most

brilliant blunder in history.

A spherical Earth

had been the general opinion of Ancient Greek

science. This view continued through the Middle Ages

among the educated. As early as the sixth

century B.C., the Greek mathematician Pythagoras

surmised the world was round, and two centuries

later Aristotle backed him up with astronomical

observations. By 1492 most educated people knew the

planet was not shaped like a pancake.

What stopped all other

explorers from trying the Western route was not the

threat of sea monsters or falling off the cliff at

the edge of the world, but rather a good grasp of

Mathematics.

|

Since their calculations said the

western route was an enormous distance, why bother? In

their opinion, the Moon might actually be closer than India

if they sailed to the west.

The game of the day was to find a sea

route to India, the land of riches. At this point in

time, the two choices were a land route through Egypt that

would someday become the Suez Canal or a lengthy sea trip

around South Africa. Both routes were painfully slow.

But to assume that going west would

produce a faster route was unthinkable!

Where Columbus differed from the

generally accepted view of his time was his (incorrect)

belief in a significantly smaller diameter for the Earth.

Columbus claimed that Asia could be easily reached by

sailing west across the Atlantic. Of course, he may have

just said that to get the job. Those costly exploring gigs

were hard to get.

For nearly a decade, Columbus lobbied

European monarchies to bankroll his quest to discover a

western sea route to Asia. In Portugal, England and France,

the response was always the same: no. And why

not?

The scholars in the day of Columbus

made calculations that pegged India as being three to four

times FURTHER to the west than to the east. A quick

look at Google Earth confirms that fact. India is

about 5,000 miles east from Portugal as the airplane flies,

but almost 20,000 miles taking the western route of

Columbus. Based on their own calculations, the

scholars dismissed Columbus's claim that the Earth was much

smaller as nonsense.

Consequently these same experts told

the monarchs of these countries that his

calculations were wrong and that the voyage would

take much longer than he thought.

Oddly enough, the royal advisors in Spain raised

similar concerns to King Ferdinand and Queen

Isabella. However, they had just gotten rid of the

Moors and were feeling lucky.

It turned out the naysayers

were right. Columbus had dramatically underestimated

the earth’s circumference and the size of the

oceans. But, luckily for him, he ran into the

uncharted Americas. We all know what happened from there.

Columbus has gone down in history as one of our greatest men.

Only recently has modern thinking suggested Columbus' discovery of the New

World was not due to skill, but rather his ignorance.

The New World had been discovered not by the greatest

explorer of the day, but by the most

incompetent one. Columbus was literally the only sailor

dumb enough to try this route. Sometimes it is better

to be lucky than good.

|

|

Sometimes incompetence is useful. It helps you keep an

open mind.

-

Roberto Cavalli

Compounding his mistake, Columbus was

so stupid that when he landed in the Bahamas, he was certain he

had found the outskirts of India!

Columbus wasn't sure what to make of his discovery. Columbus

was just barely smart enough to discern he wasn't in India, but he stuck to his guns and

assumed he was at least close to India. Columbus

concluded he had arrived in a scattering of islands just to

the east of India. Therefore Columbus decided to name this

chain of islands "The West Indies". All natives

of the West Indies were to be referred to as "Indians".

This mistake has doomed every person in America to call our

North American indigenous people "Indians" ever since.

Thanks to Columbus and his goofy math skills, everyone from

Gandhi to Geronimo are commonly

referred to as "Indians".

Believe it or not, to the end of his life in 1506, Columbus

still maintained that he had reached Asia.

Medical Follies

Columbus, unfortunately, is not the

only fool in history. He is simply the most famous

one.

These kind of follies are not limited

to astronomy, science and exploration.

The history of

Medicine is

also lined with mistakes and crazy theories.

Over the centuries, archaic concepts such as alchemy,

bloodletting, phlogiston and phrenology were once popular,

then eventually discarded. But these were just the side

shows. They were nothing compared to some of the major

medical boo-boos along the way.

For example, back in ancient

Greece, the so-called birthplace of modern medicine, doctors

like the second-century Greek physician Galen believed that

the liver (not the heart) circulated blood while the heart

circulated some sort of mystical serum known as "vital

spirit”.

It wasn't until 1628 that

English physician William Harvey let everyone in on the big

secret. He wrote a book with a catchy title - "An

Anatomical Study of the Motion of the Heart and of the Blood

in Animals". It took a while to gain acceptance, but

eventually the medical community got it right… the heart

pumps the blood, not the liver. Hard to believe,

right?

Today we take DNA for

granted as the building block of all living organisms, but

it wasn’t always that way. DNA was discovered in 1869,

but for a long time it went unappreciated. In the eyes

of the medical community, DNA was an afterthought.

Although DNA was doing all the work, no one figured that

out. DNA was always overshadowed by its flashier protein

counterparts in the minds of the researchers. Those

proteins surely held the ultimate secret to life.

Even after experiments in

the middle part of the 20th century offered proof that DNA

was indeed the genetic material, many scientists held firmly

that proteins, not DNA, were the key to heredity. DNA, they

thought, was just too simple to carry so much information.

It wasn't until Watson and

Crick published their all-important double-helical model of

DNA’s structure in 1953 that biologists finally started to

understand how such a simple molecule could do so much.

Hmm. Here’s another one.

What about germs? We take that discovery for granted too.

However, as we read in the Semmelweiss account,

even as recent as the late 19th century the

doctors didn't really see the need to wash their hands before

picking up a scalpel.

The result was a lot of gangrene.

Most early-19th century doctors tended to attribute contagion to

"bad air" and other causes. Meanwhile countless injuries

during the Civil War that should not have been life-threatening

resulted in death.

Stonewall Jackson was a notable

example. In 1863 Jackson was accidentally

shot by his own man, a sentry who lost his cool. Jackson was hit by

three bullets, two in the left arm and one in the right hand.

However, none of the wounds were considered serious.

However, sure enough, the left arm developed gangrene and had to be

amputated. His death soon followed.

Meanwhile Semmelweiss died in the insane asylum in 1865. He

had gone mad because no one would listen to him.

|

|

|

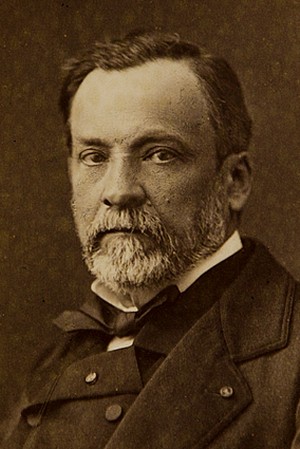

As it turned out, over in France Louis Pasteur was

working on the same issues as Semmelweiss. In

1856, Pasteur received a visit from a man called

Bigo who worked at a factory that made alcohol from

sugar beet. Bigo’s problem was that many of his vats

of fermented beer were turning sour. Much of

the beer had gone bad and had to be thrown away.

From a business point of view, this was a disaster.

Bigo asked Pasteur to find out why his beer kept

spoiling.

After using a microscope to analyze samples from the

vats, Pasteur found thousands of tiny

micro-organisms. He became convinced that they were

responsible for the beer going sour. Pasteur

believed that these organisms were the CAUSE of the

putrefaction of the beer, not the result as others

claimed.

Pasteur continued his work on this theme by studying

other liquids such as milk, wine and vinegar. In

1857, he was appointed Director of Scientific

Studies at the Ecôle Normale in Paris. Between 1857

and 1859, Pasteur became convinced that the liquids

he had studied were being contaminated with microbes

that floated in the air.

The

medical establishment ridiculed him:

"I am afraid that the experiments you quote,

M. Pasteur, will turn against you. The world

into which you wish to take us is really too

fantastic." -

La Presse, 1860

Pasteur

was vilified in public. However, rather than give up, he

was

determined to fight for what he believed in. Pasteur

started to devise tests to prove that he was right.

|

In April 1864,

Pasteur explained his beliefs in front of a gathering of

famous scientists at the University of Paris. He proved his

case beyond doubt – even if some of those present refused to

believe him. The eminent doctor Charlton Bastian stood

up and maintained his belief that putrefaction came from

within and not from invading micro-organisms.

The entire Victorian Era was filled

with controversy. First Semmelweiss, then Pasteur, then

Lister were met with open opposition for their heretical

ideas that unseen germs were causing wide-spread damage.

Fortunately not everyone was

close-minded. Once

Louis Pasteur explained his

theory of germs in the 1860s, certain

people started listening. It took a while, but doctors like

Joseph Lister realized that hospitals and doctors had the

potential to pass on life-threatening germs to patients.

Building

on Pasteur's work, Lister pioneered the idea of

actually cleaning wounds and using disinfectant. Then he

suggested doctors might think about washing their hands.

Of course now Lister came

under attack. Lister had been invited to leave

Edinburgh and join the prestigious King’s College Hospital

in London. The newspapers reported Lister as saying that it

was his duty to go to King’s because the teaching of surgery

in London was very bad.

Such publicity did not go down well

with his future London colleagues.

"Who is this ignorant

professor from an insignificant Scottish University," they

said, "that he should dare to criticize the great London

teaching-schools?"

|

|

It was left to Pasteur to finally get

it through their thick skulls that germs were the problem.

According to Dr. Emile Roux, one of

Pasteur's assistants, the actual cause of the puerperal fever was

not revealed until 11 March 1879. On that day Pasteur was

attending the Academy of Medicine in Paris and the subject

of the disease came under discussion.

One of

(Pasteur's) most weighty colleagues was eloquently

enlarging upon the causes of epidemics in lying-in

hospitals; Pasteur stood up and interrupted him from his

place.

"None

of these things cause the epidemic; it is the

nursing and medical staff who carry the microbe from

an infected woman to a healthy one."

And as the

orator replied that he feared that the microbe would

never be found, Pasteur went to the blackboard and drew

a diagram of the chain-like organism (the

streptococcus), saying:

"There, that is what it looks like!"

Pasteur's

conviction was so deep that he could not help expressing

it forcibly. It would be impossible now to picture the

state of surprise and stupefaction into which he would

send the students and doctors in attendance. With

an assurance and simplicity almost disconcerting in a

man who was entering a lying-in ward for the first time,

he criticized the hospital's appliances and declared

that all the linen should be put into a sterilizing

stove. No one said another word in opposition.

[

source ]

Thus ended the agonizing search for

the cause and prevention of puerperal fever. Vive le Pasteur!

Stories like these make you

wonder. One hundred years from now, what will people

say about today’s methods for

cancer treatment? Will people laugh and say today’s

“modern” approach to cancer treatment was the equivalent of

putting the Earth in the center of the Universe?

In my opinion, today's conventional

approach to the cure of cancer isn't working very well.

When Patrick Swayze and Steve Jobs have access to the best

cures of modern medicine and get nowhere, it is pretty hard

to have much confidence in conventional treatment.

So who is right? Who

has the right approach to the Holy Grail of a cure for

cancer? Is it Burzynski or is it

the Medical Establishment?

Ask yourself who you would put your

money on... or better yet, your life. When you get

cancer, it becomes your life you are betting on.

An old error is always more popular

than a new truth.

—

German

Proverb

All truth passes through three stages.

First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is

violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as

being self-evident.

—

Arthur

Schopenhauer

|

|

|

|

|

The Story of Smallpox

|

Smallpox was once the most feared disease in the world.

An