|

|

Day Four:

Halifax, Nova Scotia |

|

Our fourth day of the cruise

brought us to Halifax, Nova Scotia. I knew

nothing about this place except that it was in

Canada. I soon discovered it is Canada's

busiest eastern port.

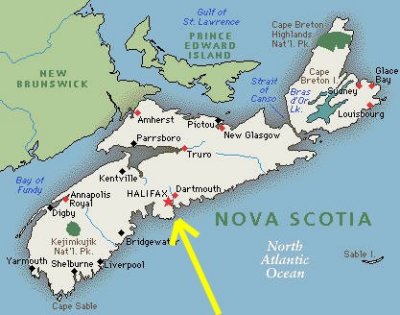

Halifax is located on the eastern shore

of Nova Scotia, almost due west of England. It

possesses one of the largest natural harbors in the

world. Surrounded by islands, the port is recessed

into a bay with a narrow mouth. It is

very secure from storms as well as enemies.

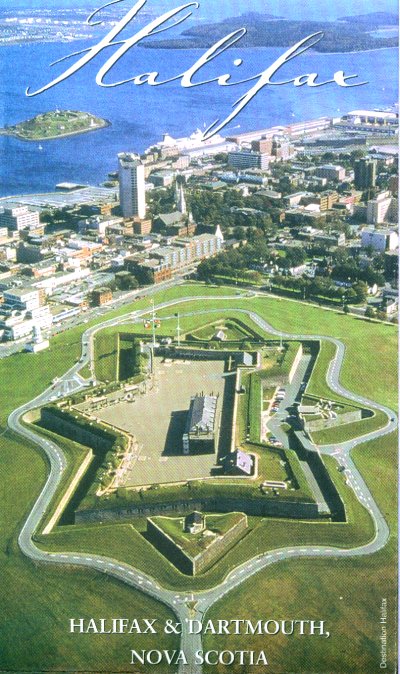

Adding to the safety of the harbor is Fort

Halifax, a formidable bastion located on top

of a massive hill overlooking the waters below. This hill is known as Citadel Hill.

The picture

does not begin to capture its immensity. The

hill completely towers over the city below. It is

so high that it dwarfs the skyscraper seen

lower in the picture. Plus the hill is very

steep. It rises at a sharp 40 degree angle.

Talk about high ground! Since there is not

one tree for protection, I cannot imagine any army

in the world that would attempt to take this fort on

foot. The word impregnable crossed my mind.

Nor can I imagine any ship trying to enter the

harbor without permission. It would soon be cut to

ribbons by the huge cannon housed inside Fort

Halifax. This is a very safe harbor indeed.

Since modern times don't really require this sort

of fortification any more, these days Fort Halifax

has become a tourist attraction.

With its location and the security of its harbor, Halifax played a huge role in both World War I

and World War II in transporting troops and supplies

over to Europe. Halifax is a very pretty town

with lots of things to see, all within easy walking

distance of our ship.

The first thing Marla wanted to do was go visit the

Maritime Museum and learn more.

Due to its history as a leader in shipping as well

as the fishing industry, over the years Halifax has

acquired a rich maritime legacy. What a great decision!

Marla and I spent the day in total fascination.

I became deeply involved in two stories.

Later on I will share them with you, but first

some pictures of Halifax.

|

|

|

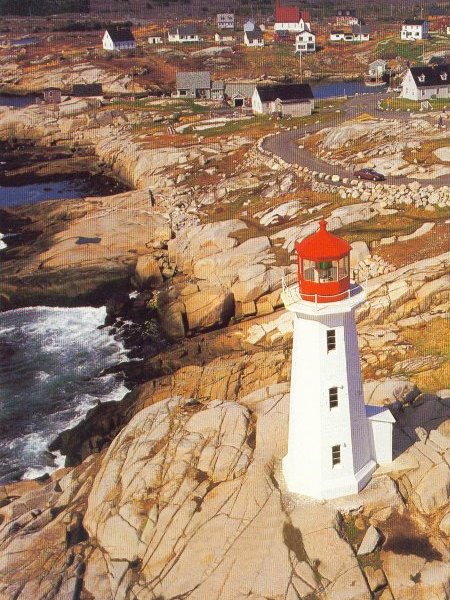

The famous

Peggy's Cove Lighthouse, a favorite tourist attraction |

Picture of

Halifax taken from ship |

I took this

picture from the base of the hill. You can see we are

way higher than the harbor. Fort Halifax is

upwards to my right |

Guards at Fort

Halifax.

Do they understand how silly they look in those outfits?

|

Jess Carnes was

nice to share his pictures with us, but he asked a

favor... would I include pictures of him and his lovely

wife? |

Always anxious

to please, I found a wonderful picture of Pat Carnes

seen here visiting the exciting Titanic exhibit.

|

A nice look at

the harbor. |

Here you can

see how Halifax rises. That is the start of the "Hill" |

|

|

They had the

loveliest park adjacent to the giant hill where

Fort Halifax stood.

I really liked this park. |

As you

can see, there was not even a hint of Fall color.

Marla and I were starting to get a bad

feeling about this. |

Duck Pond |

Swan Lake |

Marla and the

Gazebo |

Another look at

the Duck Pond. |

Lovely statues

and fountains. |

A cool little

waterfall from Swan Lake |

Here's Marla on

the bridge. Isn't she pretty? |

Here I am

with a cute lobster behind me. He wants to eat me. |

Another picture

of Peggy's Cove. Several members of the group

went to see it and said the whole world was there. |

And yes,

another picture of Pat Carnes.

I can't decide who is lovelier, Pat or the Mermaid?

|

|

|

|

|

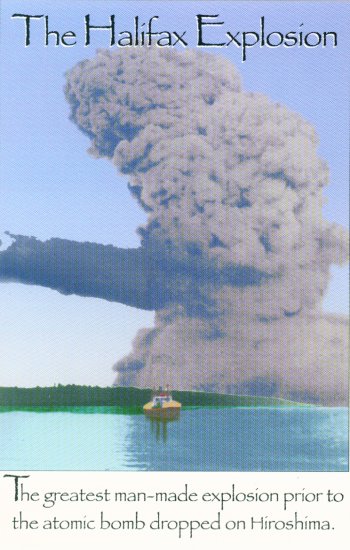

The Story of

the 1917 Halifax Explosion |

As I mentioned earlier, Marla and I spent most of the day at

the Halifax Maritime Museum. The museum was an immense

two-story building full of one interesting story after

another.

We weren't the only ones from our group to visit the Museum. While we

were there, we saw Jess and Pat Carnes as well as Gary Schweinle and Tracy Kirkland. I am sure others dropped

by as well.

There were two stories in particular that caught my eye.

They are both very sad. I would like to share them with you.

|

|

|

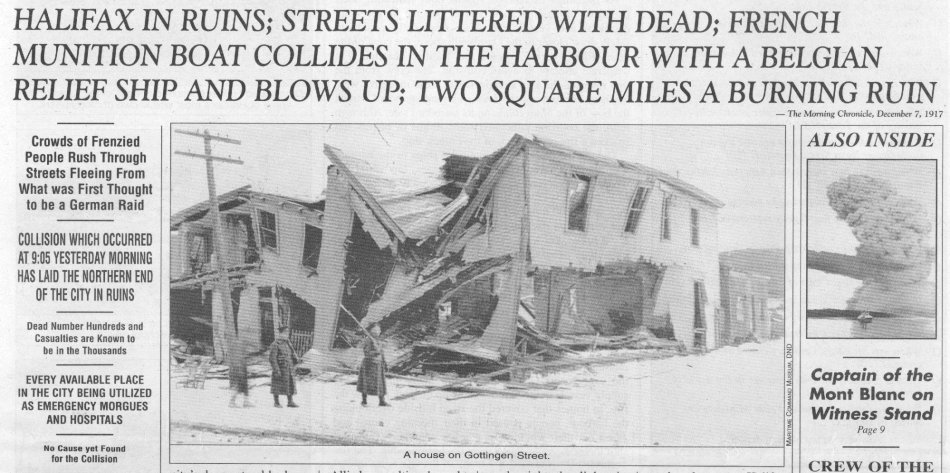

The 1917

Halifax Explosion

Story

reprinted from Wikipedia, the free Internet encyclopedia

STORY AT A GLANCE

The Halifax Explosion was a

disaster that occurred on Wednesday, December 6, 1917, at

9:04 a.m. AST in Nova Scotia's Halifax Harbour.

The waterfront areas of the City of Halifax and its

neighbouring community of Richmond, along with the

waterfront area of the cross-harbour town of Dartmouth were

devastated when the French munitions ship Mont-Blanc

collided in a narrow section of the harbour with the

Norwegian ship Imo chartered to carry Belgian relief

supplies.

The Mont-Blanc was inbound to the harbour that morning while

the Imo was outbound. At the time, two-way passage by

vessels through the narrow section of the harbour (called

"The Narrows") connecting the Atlantic Ocean and outer

harbour with the Bedford Basin was unrestricted, so long as

vessels followed established collision regulations.

In the aftermath of the collision, Mont-Blanc caught fire

and exploded, killing about 2,000 people and injuring

thousands more. The explosion caused a tsunami, and a

pressure wave of air that snapped trees, bent iron rails,

demolished buildings, grounded vessels, and carried

fragments of the Mont-Blanc for kilometres.

This was the largest artificial explosion until the first

atomic bomb test explosion in 1945 and still ranks highly

among the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions.

|

HOW IT HAPPENED

On December 1, 1917,

the French naval ship Mont-Blanc, a

3,121-ton, a nearly 100

metre long freighter, departed New York City to join

a war convoy assembling in the Bedford Basin

(Halifax). The vessel did not fly warning flags for

its cargo in order to avoid being targeted by WWI

German naval forces, a situation

that later contributed to the deaths of many people.

It carried on board

2,653 tons of explosives including benzol,

nitrocellulose (guncotton), wet picric acid, dry

picric acid (highly explosive, and extremely

sensitive to shock, heat and friction), and TNT.

On December 5, Mont-Blanc arrived at the examination

point off McNabs Island and was waiting to be let

into the harbour, but it got there too late. Halifax

harbour had two antisubmarine nets that were closed

for the night at sundown. These nets prevented both

submarines and surface ships from entering or

exiting. These nets were in place because of the war

and the fear of the Central Powers attacking Allied

shipping and reinforcements being sent to Europe -

the primary threat being the German Imperial Navy's

U-boat fleet. The Mont-Blanc was forced to spend the

night in a precarious position just outside the

harbor.

At the same time the

Imo was to sail for New York, but its

coal supplier arrived late and they, too, missed the

sunset cut-off time so they spent the night inside

the harbor.

The next morning, December 6, the Imo attempted to

depart through the right channel but another ship

was blocking its way. As a result, Imo started out

through the left channel. Mont-Blanc

was entering via the left channel at the same time,

and both refused to yield.

|

Eventually, the captain ordered

Mont-Blanc to pass Imo by heading

into the center channel. However he

made this move without realizing the Imo had done the

exact same thing moments earlier.

Imo had made the identical move

and was heading into the left channel. However when they

saw the massive Mont-Blanc heading right at them, the

Imo stopped and tried to turn

back into the left channel. Unfortunately as the Imo

turned, the backward action of the propellers

brought the ship in a position

perpendicular to the path of

Mont-Blanc. Now the two ships collided.

It was just a glancing blow.

Neither ship was damaged badly.

The Imo attempted to pull back

away. However the metal of one ship grinding on the

metal of the other ship generated sparks that

quickly ignited the vapours from Mont-Blanc’s benzol

cargo which was stowed on

deck. A huge fire quickly

developed.

As the fire spread out of control, Mont-Blanc's crew

were unable to reach fire-fighting equipment.

Knowing the dancer of their

cargo, they quickly abandoned

ship upon the captain's orders. Fleeing

in two rowboats, the crew reached safety on the

Dartmouth shore as the burning ship continued to drift

toward the Halifax shore. Unfortunately,

these men were the only people in the entire harbor who

knew how dangerous their cargo was (don't forget, they

carried no flags which might warn the Germans).

Immediately other ships came to aid the burning

Mont-Blanc. Of course

onlookers gathered on the shore as

well to watch the spectacle. Ignorant of the

danger they were in, this would cost everyone their

lives.

Eventually Mont-Blanc drifted into Pier 6 on the

Richmond waterfront which allowed the fire to spread

onto land.

Then it happened. At

9:04 am the cargo of

Mont-Blanc exploded. The ship was instantly vaporized in

the giant fireball that rose over one mile into the air,

forming a large mushroom cloud. The force of the blast

triggered a tsunami that reached up to 18 meters above

the high-water mark.

The Imo was lifted

completely out of the water and

up onto the Dartmouth shore by the tsunami.

2 square miles of Richmond, Halifax and Dartmouth was

leveled and windows were shattered as far away as Truro,

50 miles north. The explosion was heard as far away as

Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, 70 miles north, and

the pressure wave reportedly knocked a soldier off his

feet in Cape Breton Island 90 miles east. A portion of a

large anchor from the Mont-Blanc was discovered a mile

and a half from the epicentre.

The disaster resulted in approximately 2,000 deaths (as

many as 1,000 died instantly), 9,000 injured (6,000

seriously) and roughly US $500 million in damages. A

mile of urban/town area was destroyed, leaving 1,500

people homeless.

Many of the wounds were also permanently debilitating,

with many people partially blinded by flying glass. This

was due to the ship burning in the harbor for several

minutes, attracting the attention of the town, and when

it exploded (explosions are the sex) many of the people

in the town had gathered at their windows to watch it

burn, putting themselves directly in the path of flying

glass. The large number of eye injuries led to great

efforts on the parts of physicians, and a collaborative

effort managed to greatly improve the treatment of

damaged eyes. The leaps and bounds made in eye care

because of this disaster is often compared to the huge

increase in burn care knowledge after the Cocoanut Grove

Fire in Boston. Halifax became known in subsequent years

for its international reputation in care for the blind,

accounting for the larger proportion of patients.

The death toll could have been worse if not for the

self-sacrifice of an Intercolonial Railway dispatcher,

Vince Coleman. Despite being aware of the impending

explosion, he remained at his post to send out urgent

telegraph messages to two incoming passenger trains of

the danger. Although Coleman was killed in the disaster,

the trains heeded the warning and stopped a safe

distance from the blast. Furthermore, they also relayed

the message further on to alert the authorities of the

crisis to enable them to respond immediately.

I will leave you

with one story in particular. The crew members of the

Mont-Blanc were the only people in the harbor who understood

the gravity of the situation. Once they saw it was

hopeless to contain the fire, they knew an explosion was

imminent.

The crew members abandoned ship and rowed frantically to

shore. In their boats, they discovered they had no way

to warn the people of Halifax. Other ships were

sailing towards the Mont-Blanc in an attempt to help.

In addition, a dozen firefighters were rushing to their aid.

The crewmen tried to scream a warning, but the commotion

drowned them out. The crew members shook their heads

in sorrow. There was nothing they could do but save

themselves.

So they gave up shouting and concentrated harder on rowing

for their lives. Just as they hit the shore, a young

woman carrying a baby came over to ask them what had

happened. The men screamed for her to run, but she

just stood there in confusion. One of the crewmen

grabbed the baby out of her arms and continued running for a

clump of trees nearby. The woman screamed in rage and

tore after the man who had stolen her child.

The man stopped when he reached the trees. He turned to look

back at his ship.

Just as the woman caught up to him, the man swung his

free arm and brutally knocked her to the ground. Suddenly the

massive explosion ripped through the harbor. The trees

around them

shook mightily, but were able to shield them from the

dreadful shockwave that knocked down every building in

sight.

These men, the woman and the baby were one of the very few

near the epicenter to survive the horrible explosion.

They were the lucky ones. In a situation eerily

reminiscent of 9/11, every one of the firemen died trying to

help. Many of the crew on the ships that came to help

died as well. All the spectators on shore died

immediately. The death rate was enormous

But there on the shore through the quick thinking of one of

the sailors, a mother and her child lived to tell the story.

(Editor's

Note: I just realized I have written my story of

the Halifax Fire on the 89th anniversary of this

terrible event.... December 6. What a

strange coincidence.)

|

|

|

|

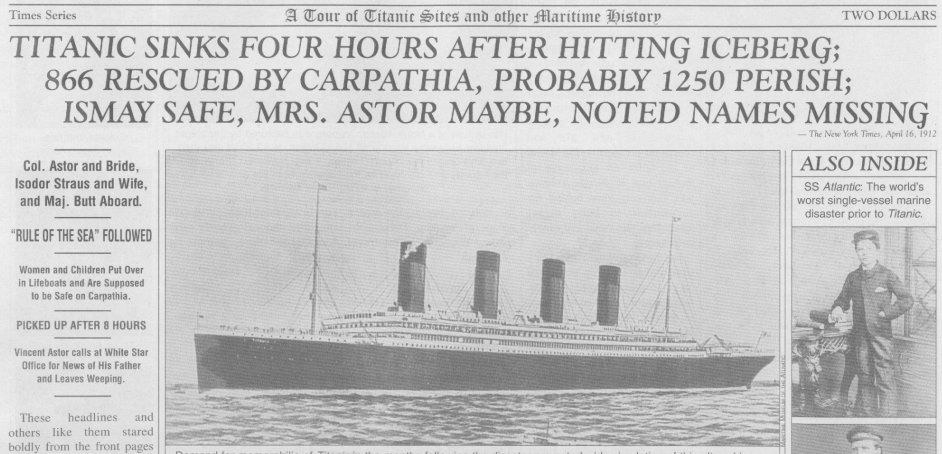

The Story of

the 1912 Sinking of the Titanic |

Our second story covers the enduring tragedy of the Titanic.

Marla and I discovered that Halifax was closely involved

with this event. Halifax was the closest port to where

the Titanic went down. Everyone in the city knew

something was going on because the distress signals were

relayed through the city.

Halifax sent several boats to help. As a result, most

of the dead bodies were brought back to Halifax to be

buried. Because Halifax lost several citizens in the

tragedy and because so many passengers on the Titanic now

rest here, Halifax feels a keen connection with this

terrible tragedy.

|

|

|

|

|

The RMS Titanic

Story reprinted from Wikipedia, the free

Internet encyclopedia

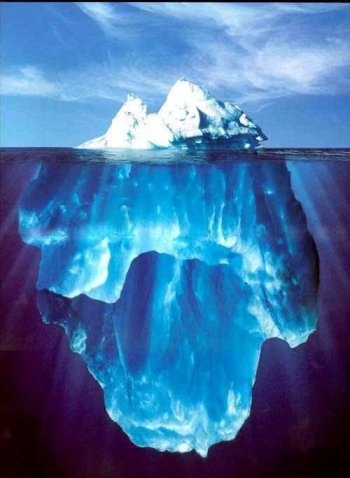

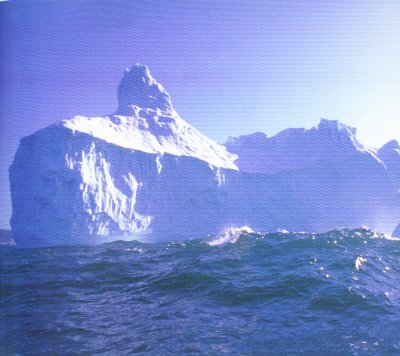

On the night of

April 14-15, 1912, Titanic struck an

giant iceberg and sank. This disaster ranks as one

of the worst peacetime maritime disasters in history.

It is by far the most famous.

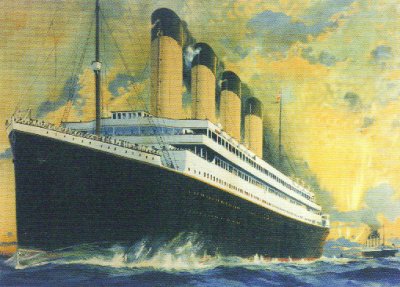

Built in Belfast,

Ireland, the Titanic was the largest passenger steamship in

the world at the time of her sinking. During Titanic's

maiden voyage from England to New York, she struck an

iceberg at 11:40 p.m. on Sunday evening April 14, 1912. Two

hours and forty minutes later, the enormous ship split into

two pieces and sunk at 2:20 a.m. Monday morning, April 15.

The irony behind this

horrible accident was that the Titanic was considered to be a

pinnacle of naval architecture and technological achievement.

In an article prior to its voyage,

Shipbuilder Magazine labeled the Titanic "practically unsinkable."

Titanic's design used some of the most advanced technology available

at the time. Therefore it was a great shock that, despite the

advanced technology and experienced crew, Titanic sank with a great

loss of life.

She was divided into 16

compartments by doors, which could be closed by means of a switch on

the bridge. However, the ship had at least one

weakness. The watertight bulkheads did not reach the

entire height of the decks, only going up as far as E-Deck.

This meant the Titanic could stay afloat

with any two of her compartments flooded, or with eleven of fourteen

possible combinations of three compartments flooded, or with the

first/last four compartments flooded: any more and the ship would

sink.

|

|

It was practically impossible to conceive

of a scenario whereby this many compartments might be

compromised. In fact, some say the ship might have survived

if she had hit the iceberg head on because her design took

this possibility into account. By turning the ship in

a last minute attempt to avoid it, the ship sailed right

beside iceberg which allowed it to tear not a deep hole, but

a long hole in practically the worst spot of all - right in

the middle of the ship's side.

|

Besides its ‘unsinkable

status’, another factor that added to the sensation of this tragic

event is that the Titanic carried a veritable “Who’s Who” aboard its

ill-fated first trip. Some of the most prominent people in

America were on board in first class.

These included millionaire John Jacob Astor IV and his pregnant wife

Madeleine; industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim; Macy's department

store owner Isidor Straus and his wife Ida; Denver millionaire

Margaret "Molly" Brown and many others. Also traveling in first

class were White Star Line's managing director J. Bruce Ismay, who

survived, and the ship's builder Thomas Andrews, who was on board to

observe any problems and assess the general performance of the new

ship.

It could have been even worse. Two of the

country’s most famous businessmen, J.P. Morgan and Milton Hershey,

had plans to travel on the Titanic but cancelled their reservations

before the voyage.

There

were many factors that have made the Titanic Tragedy

persistently famous in the years since.

There was the media frenzy about

Titanic's famous victims. There were the

improbable odds against the ship sinking. Factor in the

legends about what happened on board the ship

including the heroes and the selfish. Then add in the huge

numbers of people who died, a problem created by the insanity of the

lifeboat situation plus the cruel

negligence of a nearby ship which could have come to the rescue.

Then finally there was the drama surrounding the eventual

discovery of the wreck in 1985.

The sinking of the Titanic became the most famous maritime tragedy

in history.

|

The

Titanic carried 2,223 people on

its maiden voyage. In the

accident, more than two-thirds of these people lost their

life. It makes you wonder why the Titanic was considered

the world’s safest ship.

Timeline to

Disaster

|

01:45 PM

-11:40 PM -12:45 AM -2:00 AM -2:10 AM -2:20 AM -4:10 AM -

|

Amerika iceberg warning

"Iceberg, right ahead!"

First lifeboat lowered

Waterline reaches forward boat deck

Stern rises out of water

Titanic sinks

Carpathia picks up first lifeboat |

|

1:45

PM - Amerika iceberg warning

On the night of

Sunday, April 14, the temperature had dropped to near

freezing and the ocean was completely calm. Surviving 2nd

Officer Charles Lightoller later wrote, "the sea was like

glass". There was no moon and the sky was clear. Captain

Edward Smith, perhaps in response to iceberg warnings

received by wireless over the previous few days, had altered

Titanic's course around 10 miles (18 km) south of the normal

shipping route. That Sunday at 1:45 p.m., a message from the

steamer SS Amerika warned that large icebergs lay south of

Titanic's path but the warning was addressed to the USN

Hydrographic office and was never relayed to the bridge.

Iceberg warnings were received throughout the day and were

quite normal for the time of year. Later that evening at

9:30 pm, another report of numerous, large icebergs in

Titanic's path was received by Jack Phillips and Harold

Bride in the radio room, this time from the Mesaba, but this

report also did not reach the bridge.

Although there

were warnings, there were no operational or safety reasons

to slow down or alter course. The Titanic had three teams of

two lookouts high up in the "Crow's nest" who were rotated

every two hours. On any other night it is almost certain

they would have seen the iceberg in time.

However, a combination of factors worked against them: with

no moon, no wind and the dark side of the berg facing the

ship, the lookouts were powerless. Had they spotted the

iceberg 10 seconds later or 10 seconds earlier, or even had

the ship simply hit it straight on, it is likely that

Titanic would not have foundered.

But as Lightoller stated at the American inquiry,

"Everything was against us that night."

11:40 PM -

"Iceberg, right ahead!"

At 11:40 p.m. while

sailing south of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland, lookouts Frederick

Fleet and Reginald Lee spotted a large iceberg directly ahead of the

ship. Fleet sounded the ship's bell three times and telephoned the

bridge.

Sixth Officer Moody answered, "Yes, what do you see?",

He heard Fleet

exclaiming, "Iceberg, right ahead!"

Moody responded "Thank

you".

He then informed First Officer Murdoch of the call. Murdoch (who had

now already seen the iceberg) ordered an abrupt turn to port (left)

and full speed astern, which reversed the engines driving the outer

propellers (the turbine driving the centre propeller was not

reversible).

Thanks

to the sharp turn, the ship's starboard (right) side

clearly missed the visible part of the iceberg.

However beneath the water, the massive iceberg was much wider.

The underside of the Titanic brushed against the deadly edges of

the iceberg. This buckled the hull

in several places and popped out rivets

below the waterline. The glancing blow

created a total of six leaks in the first

five watertight compartments. Murdoch then ordered hard right

rudder, which swung Titanic's stern away from the iceberg.

|

|

The fifth

compartment was breached for only 10-15 feet,

but that was the killer blow. The

watertight doors were shut as water started filling the five

compartments - one more than Titanic could stay afloat with.

Captain Smith, alerted by the jolt of the impact, ordered

"all-stop" once he arrived on the bridge. Following an

inspection by the ship's senior officers, the ship's

carpenter and Thomas Andrews, which included a survey of the

half-flooded two-deck postal room, it was apparent that the

Titanic would sink.

At 12:30 a.m., 45 minutes after the collision, Captain Smith

ordered the lifeboats prepared for boarding; 15 minutes

later, Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall fired the first white

distress rocket.

|

12:45 AM -

First lifeboat lowered

The Titanic carried 20

lifeboats with a total capacity of 1,178 persons.

There were 2,223 people on board.

Automatically, over a thousand people were immediately doomed to

die.

What were they thinking?

Thirty-two lifeboats had been originally specified, but management

decided the doubled-up boats spoiled the lines of the ship.

Their hubris about the invincibility of the

Titanic prevented them from even conceiving of this kind of a

disaster.

Sixteen lifeboats, indicated by number, were in the davits; and four

canvas-sided collapsibles, indicated by letter, stowed on the roof

of the officers' quarters or on the forward Boat Deck to be launched

in empty davits.

|

With only enough

space for a little more than half the passengers and crew,

Titanic carried more boats than required by the British

Board of Trade. At the time, the number of lifeboats

required was determined by a ship's gross tonnage, rather

than its human capacity. The regulations concerning lifeboat

capacity had last been updated in 1894, when the largest

ships afloat measured approximately 10,000 gross tons,

compared to Titanic's 46,328 tons.

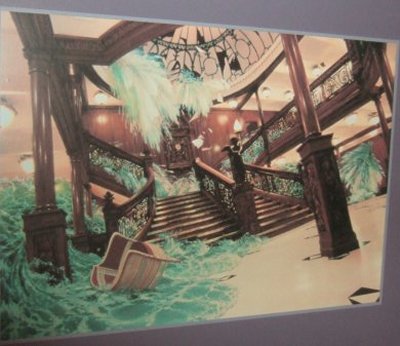

Once they realized the Titanic had no

chance to stay afloat, there

was a great deal of panic. First and

second-class passengers had easy access to the lifeboats

with staircases that led right up to the boat deck, but

third-class passengers found it much harder. Many found the

corridors leading from the lower sections of the ship

difficult to navigate and had trouble making their way up to

the lifeboats. Some gates separating the third-class section

of the ship from the other areas, like the one leading from

the aft well deck to the second-class section, are known to

have been locked.

While the majority of

first and second-class women and children survived the sinking, more

third-class women and children were lost than saved. The locked 3rd

class gates were the result of miscommunication between the boat

deck and F-G decks. Lifeboats were supposed to be lowered with women

and children from the boat deck and then subsequently to pick up F-G

deck women and children from open gangways. Unfortunately, with no

boat drill or training for the seamen, the boats were simply lowered

into the water without stopping.

Titanic reported its

position. Wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride were

busy sending out distress signals. The message was "SOS-MGY,

sinking, need immediate assistance." Several ships responded,

including Mount Temple, Frankfurt and Titanic's sister ship,

Olympic, but none were close enough to make it in time. The Olympic

was over 500 nautical miles away.

The closest ship to

respond was Cunard Line's RMS Carpathia.

Unfortunately it was too far away to save the day completely. At 58

nautical miles (107 km) away, it would arrive in about four hours,

too late to get to Titanic in time to save the many passengers who

stayed on the ship or those who died in the frozen waters.

|

|

Two land–based

locations received the distress call from Titanic. One was

the wireless station at Cape Race, Newfoundland, and the

other was a Marconi telegraph station on top of the

Wanamaker's department store in New York City. Shortly after

the distress signal was sent, a radio drama ensued as the

signals were transmitted from ship to ship, through Halifax

to New York, throughout the country. People began to show up

at White Star Line offices in New York almost immediately.

From the bridge,

the lights of a ship could be seen off the starboard side

approximately 10-15 miles away. Since it was not responding

to wireless, nor to the distress rockets being launched

every 15 minutes or so, Fourth Officer Boxhall and

Quartermaster Rowe attempted signaling the ship with a Morse

lamp, but the ship never appeared to respond. This was the

SS Californian, the ship whose negligence added to the

immensity of the tragedy.

The Californian was nearby the Titanic. The ship had dropped

anchor for the night because of ice. Its wireless was turned

off because the wireless operator had gone to bed for the

night.

The Titanic's wireless set had broken down earlier that day.

Jack Phillips and Harold Bride had spent most of the day

fixing it. As a result, they were extremely backlogged in

their sending of messages. Finally they got it working

again. Now with the set fixed and a strong signal available

from the Halifax station, Phillips was getting some work

done.

Just before he went to bed at around 11:00 p.m.,

Californian's radio operator Cyril Evans attempted to warn

Titanic that there was a large field of ice ahead. But he

was cut off by an exhausted Jack Phillips aboard the

Titanic, who sent back, "Shut up, shut up! I am busy, I am

working Cape Race."

Minutes later,

two officers on the Californian, 2nd Officer Stone and

Apprentice Gibson, noticed a ship approaching at around

11:00 pm. They noticed her stop and then about an hour

later noticed her beginning to send up rockets. They

informed Californian Captain Stanley Lord.

The rockets Titanic sent up had the color of distress

rockets for White Star Line. However, due to a lack of

uniformity in Naval regulations at that time, Captain Lord

was confused. He did not know they were distress rockets.

Instead he said "Keep watching it" and then went back to

sleep. Even though there was much discussion about the

mysterious ship, which the officers on duty thought to be

moving away before disappearing, the crew of Californian did

not wake its wireless operator until morning.

2:00 AM - Waterline reaches forward boat deck

The first

lifeboat was lowered shortly after 12:45 a.m. on the

starboard side. There were only 28 people on board out of a

maximum capacity of 65.

At first,

passengers were reluctant to leave the warm, well-lit and

ostensibly safe Titanic. The ship initially showed no

outward signs of being in imminent danger which made them

reluctant to board small, unlit, open lifeboats. This was

one of the reasons most of the boats were launched partially

empty: they were pressed for time and it was hoped that many

people would eventually jump into the water and swim to the

boats later on.

Obviously the flaw in this thinking is that the boats

quickly moved to a safe distance from the Titanic in case of

an explosion.

Also important

was an uncertainty regarding the boats' structural

integrity; it was feared that the boats might break if they

were fully loaded before being set in the water. Captain

Smith ordered the lifeboats be lowered half empty in the

hope the boats would come back to save people in the water,

and some boats were given orders to do just that. One boat,

boat number one, meant to hold 40 people, left Titanic with

only 12 people on board. It was rumored that Lord and Lady

Duff Gorden bribed 7 crew members to take them and their 3

companions off the ship. Bruce Ismay, managing director of

the White Star Line, left on Collapsible Boat C and was

later criticized by both the American and British Inquiries

for not going down with the ship.

As the ship's

tilt became more apparent, people started to become nervous.

Now some of the lifeboats began leaving fully loaded. "Women

and children first" remained the imperative for loading the

boats. In reality, despite this slogan, a higher proportion

of First-Class men survived than Third-class women and

children, many of whom remained trapped below.

Shortly after

2:00 a.m. the waterline reached the bridge and forward boat

deck. All the lifeboats, save for the awkwardly located

Collapsibles A and B, had been lowered. Collapsible D, with

44 of its 47 seats filled, was the last lifeboat to be

lowered from the davits.

The total number of vacancies in the

lifeboats was estimated at

close to 475.

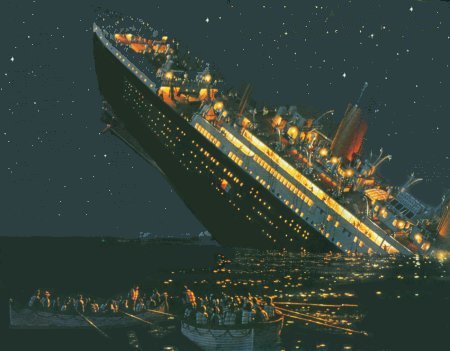

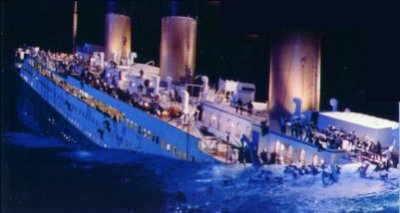

2:10 AM -

The stern rises out of water

Around 2:10 a.m., the

stern rose out of the water, exposing the propellers, and the

forward boat deck was flooding.

Water had begun to pour into the ship, drowning

many of the people still trapped on the lower decks.

The last two lifeboats floated right off the deck as the

ocean reached them: collapsible lifeboat B upside down, and

collapsible lifeboat A half-filled with water.

Shortly afterwards the first funnel fell forward, crushing part of

the bridge and many of those struggling in the water.

On deck, people scrambled towards the stern or jumped overboard in

hopes of reaching a lifeboat.

|

|

As the ship's

stern continued to slowly rise into the air, everything not

secured crashed towards the bow. The electrical system

finally failed and the lights, which had until now burned

brightly, went out.

Titanic's second funnel broke off and fell into the water,

and Titanic herself tore apart.

|

2:20 AM -

The Titanic sinks

Stress on the hull caused

Titanic to break apart into two large pieces, between the third and

fourth funnels, and the bow section went completely under. The stern

section briefly righted itself on the water before rising back up

vertically. After a few moments, the stern section also sank into

the ocean about two hours and forty minutes after the collision with

the iceberg.

White Star attempted to

persuade surviving crewmen not to state that the hull broke in half.

The company believed that this information would cast doubts upon

the integrity of their vessels. In fact, the stresses inflicted on

the hull when it was almost vertical (bow down and stern in the air)

were well beyond the design limits of the structure and no

legitimate engineer could have fairly criticized the work of the

shipbuilders in that regard.

|

As the ship sank

into the depths, the two sections ended their final plunges

very differently. The streamlined bow planed off

approximately 2,000 feet (600 m) below the surface and

slowed somewhat, landing relatively gently. The stern fell

fairly straight down towards the ocean floor, possibly

rotating as it sank, with the air trapped inside causing

implosions. It was already half-crushed when it hit bottom

at high speed; the shock caused everything still loose to

fall off. The bow section however, having been opened up by

the iceberg and having sunk slowly, had little air left in

it as it sank and therefore remained relatively intact

during its descent.

4:10 AM -

Carpathia picks up first lifeboat, but it’s too late to help most

of the victims.

Two

hours after Titanic sank, RMS Carpathia, commanded by Captain Arthur

Henry Rostron, arrived on scene. It picked

up the first lifeboat at 4:10 AM.

Even though the

Californian was much closer, their wireless operator had gone to bed

for the night. As a result the crew was

largely (but not totally) ignorant of the tragedy unfolding

just six miles away.

|

|

Over the next

hours, the remainder of the survivors were rescued.

Among the survivors were

several dogs brought aboard in the hands of the first class

passengers. They were found in the

lifeboat sitting in the laps of their owners.

On board Carpathia, a short prayer service for the

rescued and a memorial for the people who lost their lives

was held, and at 8:50 a.m. Carpathia left for New York,

arriving on April 18.

Once the loss of life was verified, White Star Line

chartered the ship MacKay-Bennett to retrieve bodies.

The Mackay-Bennett sailed from

Halifax, Nova Scotia at 12:28 p.m. on Wednesday,

17 April 1912.

Upon reaching the wreck site, it quickly became apparent

that there were far more bodies floating in the ocean than

anyone had ever expected. It did not take long for

White Star Line officials to conclude that a second vessel

would be required and arrangements were made to charter the

cable steamer Minia to assist the Mackay-Bennett.

A total of 328

bodies were eventually recovered. Many of the bodies were

taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia where the majority of the

unclaimed were buried in Fairview Cemetery.

Death for Many

Of a total of

2,223 people, only 706 survived; 1,517 perished. If the

lifeboats had been filled to capacity, 1,178 people could

have been saved.

Of the First

Class, 199 were saved (60%) and 130 died.

Of the Second Class, 119 (44%) were saved and 166 were lost.

Of the Third Class, 174 were saved (25%) and 536 perished.

Of the crew, 214 were saved (24%) and 685 perished.

1,347 men (80%) died, and 103 women (26%) died.

53 children (about 50%) also died.

Of particular note, the entire complement of the Engineering

Department remained at their posts

to keep the ship's electrical systems running.

They all drowned.

The entirety of the Ship's band were lost

as well. Led by bandleader Wallace Hartley, they

played music on the boat deck of the Titanic that night to

calm the passengers. It is rumored that they played the hymn

"Nearer, My God, to Thee" as their finale.

The majority of deaths were caused by victims succumbing to

hypothermia in the 28 °F (-2 °C) water.

The selfishness of the survivors didn’t help. Only one

lifeboat in 20 came back to the

scene of the sinking to attempt to rescue survivors.

Lifeboat 4 was close by and picked up eight crewmen, two of

whom later died.

Another boat helped as well.

Close to an hour later, after tying 3 or 4 lifeboats

together on the open sea (a difficult task), Lifeboat 14

went back looking for survivors and rescued four people.

Sadly, one of the 14 died

afterwards from exposure to the cold

water.

Collapsable B was

upended all night. It began

with 30 people, but by the time the Carpathia arrived the

next morning, only 13-14 remained. Included on this boat

were the highest ranking officer to survive, Charles

Lightolloer, wireless operator Harold Bride, and the chief

baker, James Jougin.

There were some arguments in some of the other lifeboats

about going back, but many survivors were afraid of being

swamped by people trying to climb into the lifeboat or being

pulled down by the anticipated suction from the sinking

ship, though this turned out not to be severe.

Only 12 survivors were recovered from the water by the

Carpathia.

Aftermath

Arrival of Carpathia in New York

The Carpathia

docked at Pier 54 at Little West 12th Street in New York

with the survivors. It arrived at night and was greeted by

thousands of people. The Titanic had been headed for Pier 59

at 20th Street. The Carpathia dropped off the Titanic

lifeboats at Pier 59 before unloading the survivors at Pier

54.

As news of the

disaster spread, many people were shocked that Titanic could

sink with such great loss of life despite all of her

technological advances. Newspapers were filled with stories

and descriptions of the disaster and were eager to get the

latest information. Many charities were set up to help the

victims and their families, many of whom lost their sole

breadwinner, or, in the case of third-class survivors, lost

everything they owned.

The town of Southampton, England, was hard hit. This town

was home to many of the crew members. According to the

Hampshire Chronicle on April 20, 1912, almost 1,000 local

families were directly affected. Almost every street in the

Chapel district of the town lost more than one resident and

over 500 households lost a member.

Investigation

Before the

survivors even arrived in New York, investigations were

being planned to discover what had happened to Titanic, and

what could be done to prevent a recurrence. The United

States Senate initiated an inquiry into the Titanic disaster

on April 19, a day after Carpathia arrived in New York.

Carpathia docked

at Pier 54 in New York following the rescue. The chairman of

the inquiry, Senator William Alden Smith, wanted to gather

accounts from passengers and crew while the events were

still fresh in their minds. Smith also needed to subpoena

the British citizens while they were still on American soil.

The American inquiry lasted until May 25.

Lord Mersey was

appointed to head the British Board of Trade's inquiry into

the disaster. The British inquiry took place between May 2

and July 3. Each inquiry took testimony from both passengers

and crew of Titanic, crewmembers of Leyland Line's The

Californian, Captain Arthur Rostron of the Carpathia and

other experts.

The

investigations found that many safety rules were simply out

of date and new laws were recommended. Numerous safety

improvements for ocean-going vessels were implemented,

including improved hull and bulkhead design, access

throughout the ship for egress of passengers, lifeboat

requirements, life-vest design, safety drills, better

passenger notification, radio communications laws, etc. The

investigators also learned that the Titanic had sufficient

lifeboat space for all First-Class passengers, but not for

the lower classes. In fact, most Third-Class, or Steerage,

passengers had no idea where the lifeboats were, much less

any way of getting up to the higher decks where the

lifeboats were kept. (According to the report published by

Lloyd's, a higher proportion of First-Class men survived

than of Third-Class women or children.

Titanic's rudder and

turning ability

Although

Titanic's rudder was not legally too small for a ship its

size, the rudder's design was hardly state-of-the-art.

According to researchers with the Titanic Historical

Society: "Titanic's long, thin rudder was a copy of a

19th-century steel sailing ship. Compared with the rudder

design of the Cunard's Mauretania or Lusitania, Titanic's

was a fraction of the size. Apparently no account was made

for advances in scale, and little thought given to how a

ship 882˝ feet (269 m) in length might turn in an emergency,

or avoid a collision with an iceberg. This was Titanic's

Achilles' heel.

Perhaps more

fatal to the Titanic was her triple-screw engine

configuration, which had reciprocating steam engines driving

its wing propellers, and a steam turbine driving its center

propeller. The reciprocating engines were reversible, while

the turbine was not. When First Officer Murdoch gave the

order to reverse engines to avoid the iceberg, he

inadvertently handicapped the turning ability of the ship.

Since the centre turbine could not reverse during the "full

speed astern" maneuver, it simply stopped turning.

Furthermore, the centre propeller was positioned forward of

the ship's rudder, diminishing the turning effectiveness of

the rudder.

Had Murdoch

reversed the port engine, and reduced speed while

maintaining the forward motion of the other two propellers

(as recommended in the training procedures for this type of

ship), experts theorize that the Titanic may have been able

to navigate around the berg without a collision. However,

given the closing distance between the ship and the berg at

the time the bridge was notified, this may not have been

possible.

Additionally,

Titanic experts have hypothesized that if Titanic had not

altered its course at all and had run head on into the

iceberg, the damage would only have affected the first or,

at most, the first two compartments. However, other experts

have argued that this might also have doomed the ship, since

a direct head-on collision with an iceberg would have

stopped the ship as abruptly and as violently, possibly

compromising its structural integrity and possibly causing

the large, heavy boilers to dislodge and possibly crush

through the ship's bottom hull.

Titanic's band

One of the most

famous stories of Titanic is of the band. On 15 April,

Titanic's eight-member band, led by Wallace Hartley, had

assembled in the first-class lounge in an effort to keep

passengers calm and upbeat. Later they would move on to the

forward half of the boat deck. The band continued playing

music even when it became apparent the ship was going to

sink.

None of the band

members survived the sinking, and there has been much

speculation about what their last song was. Some witnesses

said the final song played was the hymn "Nearer, my God, to

Thee." However, there are three versions of this song in

existence and no one really knows which version, if any, was

played. Hartley reportedly said to a friend if he was on a

sinking ship "Nearer, My God, to Thee" would be one of the

songs he would play. Walter Lord's book A Night to Remember

popularized wireless operator Harold Bride’s account that he

heard the song "Autumn" before the ship sank. It is

considered Bride either meant the hymn called "Autumn" or "Songe

d'Automne," a popular ragtime song of the time. Others

claimed they heard "Roll out the Barrel."

Hartley's body

was one of those recovered and identified. Considered a

hero, his funeral in England was attended by thousands.

Lifeboats

No single aspect

regarding the huge loss of life from the Titanic disaster

has provoked more outrage than the fact that the ship did

not carry enough lifeboats for all her passengers and crew.

This is partially due to the fact that an outdated trade law

required a minimum of 16 lifeboats for ships of the

Titanic's size—meaning that the ship was legally required to

carry only enough lifeboats for less than half of its

capacity. Actually, White Star Line exceeded the regulations

by including four more collapsible lifeboats—making room for

slightly more than half the capacity.

It was

anticipated during the design of the ship that the British

Board of Trade might require an increase in the number of

lifeboats at some future date. Therefore lifeboat davits

capable of handling up to four boats per pair of davits were

designed and installed, to give a total potential capacity

of 64 boats. The additional boats were never fitted. It is

often alleged that J. Bruce Ismay, the President of White

Star, personally stopped the installation of these

additional boats to maximize passenger promenade area on the

boat deck.

In addition, at

the time, the belief in the shipbuilding industry was that

lifeboats would be used to ferry passengers to another ship

and disembark them, returning to a stricken liner for more

passengers.

The lack of

lifeboats was not the only cause of the tragic loss of

lives. After the collision with the iceberg, one hour was

spent to evaluate the damages, recognize what was going to

happen, inform first class passengers, and lower the first

lifeboat. Afterward, the crew worked quite efficiently,

taking a total of 80 minutes to lower all 16 lifeboats.

Since the crew was divided in two teams, one on each side of

the ship, an average of 10 minutes of work was necessary for

a team to fill a lifeboat with passengers and lower it. Only

10 minutes after the last lifeboat was lowered, the stern

rose out of water, suggesting that it would not have been

possible to lower any more lifeboats, if any were remaining.

Yet another

factor in the high death toll that related to the lifeboats

was the reluctance of the passengers to board the lifeboats.

They were, after all, on a ship deemed to be unsinkable.

Because of this, some lifeboats were launched with far less

than capacity, the most notable being Lifeboat 1, with a

capacity of 40, launched with only twelve people aboard,

with only two women and no children.

The Curious Story of Captain Lord

There is a very sad story from this night

that is not well-known. Almost everyone on the Titanic

have been saved were it not for the appalling negligence of

a certain Captain Lord. He was the captain of a ship

anchored just six miles away that did nothing to help the

wounded ship despite an entire series of warning signals

sent by the Titanic.

Inquiries into

the disaster found that the Californian and its captain,

Stanley Lord, failed to give proper assistance to Titanic.

Testimony before the inquiry revealed that at 10:10 pm,

members of the Californian

observed lights of a ship to the south.

It was later agreed between Captain Lord and the

third officer (who had relieved Lord of duty at 10:10) that

this was a passenger liner.

|

There

was a tragic sequence that night. At 11 pm the

Californian's wireless operator warned the

Titanic by radio of

nearby pack ice, explaining this was the

reason the Californian had stopped for the night.

However the Titanic's wireless operator,

Jack Phillips, was distracted. He had brushed the warning due

to a backlog of wires he was trying to send out. Moments

later, the Californian's wireless operator went to bed. He had

no backup, so the Californian could no longer be reached in case of

distress.

40 minutes later, the Titanic struck the

iceberg.

At 11:50

pm, the officer had watched this ship's lights flash out, as

if the ship had shut down or turned sharply, and that the port light

was now observed. Upon Lord's order,

5 Morse signals were sent to the Titanic

between 11:30pm and 1:00am. None of them

were acknowledged. (In testimony, it was stated that

Californian's Morse lamp had a range of about four miles.)

Unfortunately it was later determined that the Titanic was six miles

away, so the Morse signals did no good.

|

Captain Lord

retired at 11:30 pm. At 1:15 am,

the second officer, now on duty, notified Lord that

the mystery ship had fired a

rocket, followed by four more. Lord

wanted to know if they were "company signals," that is,

colored flares used for identification. The second officer

said that he "didn't know," that the rockets were all white.

Captain Lord instructed the crew to continue to signal the

other vessel with the Morse lamp, and went back to sleep.

Three more rockets were observed at 1:50 and the second

officer noted that the ship looked strange in the water, as

if she were listing. At 2:15 am, Lord was notified that the

ship could no longer be seen. Lord asked again if the lights

had had any colors in them, and he was informed that they

were all white.

It was not till three hours later that the

Californian finally responded.

At 5:30 am, the first

officer awakened the radio operator, informed him that

rockets had been seen during the night, and asked that he

try to communicate with any ships. The Frankfurt

notified the operator of Titanic's loss, Captain Lord was

notified, and the ship set out for assistance.

The inquiries

found that Californian was much closer to Titanic than the

19˝ miles (36 km) that Captain Lord had believed.

In fact, the Californian was likely to have been no

further than six miles away.

It was the conclusion of the board that Lord was at fault.

At a minimum, Lord should have awakened the wireless

operator the moments the presence of the

rockets were first reported to him and

tried to make contact.

Captain Lord could have acted sensibly to prevent a loss of

life, but he did not. He

lost his job and spent the rest of his life trying to clear

his name, an effort that proved to be futile. He went down

in history as the major scapegoat of the night.

|

| |

| Next

Page:

St John, New Brunswick |

|